I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

CEO pay trends in Australia are unjustifiable on any reasonable grounds

The latest report from the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors released on Thursday (August 24, 2017) – CEO Pay in ASX200 Companies: 2016 – shows how unfair and unsustainable the income distribution is in Australia. While there has been moderation in the growth of CEO pay after the ‘greed is good’ binge leading up to the GFC, the managerial class in Australia has still enjoyed real growth in pay at a time when the average worker is enduring either flat to negative growth in pay. Further, overall economic growth in Australia is being driven by increased non-government indebtedness as real wages growth (what there is of it) lags well behind productivity growth. And, at the same time, the Federal Government is intent on pursuing an austerity policy stance. All these trends are similar to the dynamics we experienced in the lead-up to the GFC. They are unsustainable. A major shift in income distribution away from capital towards workers has to occur before a sustainable future is achieved. The indicators are that there is no pressure for that to occur.

Late last week it was disclosed that the out-going Australia Post (a state-owned company) was given a departing payment of $A10.8 million which included $A8.7 million in bonuses on top of his base salary of $A2.04 million per year.

The state secretary of the Communications Workers Union, which covers Australia Post workers responded with:

… It is obscene that Ahmed Fahour is walking away with nearly $11 million as a pay-off for slashing the postal services of all Australians. Our members, who are receiving a less than CPI [inflation] pay rise, are absolutely outraged.

When his base salary was disclosed earlier in the year, the public outrage was so great that the CEO was forced to resign, although they massaged this as being a natural transition.

This was similar to the recent announcement surrounding the announcement that the CEO of the privatised public bank – Commonwealth Bank of Australia – was resigning, not long after the Bank was charged with 53,700 contraventions of Australia’s money laundering and terrorism laws.

The Authority charged with maintaining the integrity of transactions (AUSTRAC) has said that the CBA failed to report a massive number of suspicious transactions (Source).

That was the latest in the sequence of scandals the CBA has been involved in as it chases profits without regard to workers, customers and, it seems, probity.

And today there was news (August 28, 2017) – Commonwealth Bank facing APRA probe – that the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has announced an:

… inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank’s culture, governance, and accountability systems, prompted by a run of run of scandals at the country’s largest lender.

They cited a public distrust for the CBA after a series of obvious failures at the highest level of the bank.

The Australia Post CEO received the ridiculously-large bonuses for doing things like pushing through increases in stamp prices (from 70 cents to $A1) and forcing workers into six-day deliveries. Priorities!

The Australia Post board tried to claim they had to pay this salary/bonus level to attract the right talent. Two questions arise:

1. Why is the incoming CEO going to be paid “$1.375 million a year, with the potential to earn 100 per cent of that as a bonus”? (Source).

2. Why are similar executives in the US paid on average $US230,090 per year (2016) if $A10 million or so is required to attract talent (Source)?

As noted in the Introduction, the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors published its latest annual CEO pay survey last Thursday (August 24, 2017) – CEO Pay in ASX200 Companies: 2016.

It covers executive pay for the 200 listed companies on the Australian Stock Exchange.

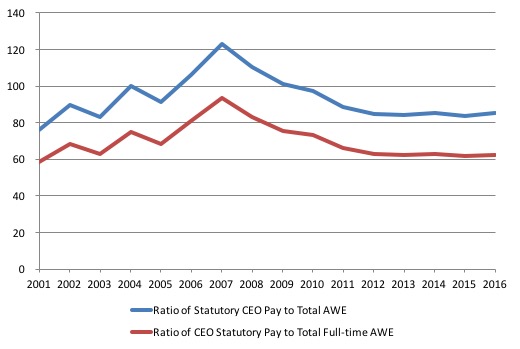

The survey shows that in 2001 (when the first survey was taken) the ratio of average CEO pay to total earnings by workers was 76 to 1. By 2016 this ratio was 85 to 1, although it peaked at 123 to 1 in 2007 just before the crisis.

I have already discussed on several occasions the widening gap between productivity growth and real wages growth, which manifests as an increasing profit share in national income and a decreasing wage share.

This redistribution of national income towards capital has been ongoing for the last three decades or so in most countries and is a characteristic of the neo-liberal era.

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go?

Answer: Some of the redistributed income has been retained by firms and invested in financial markets fuelling the speculative bubbles around the world.

But some of the redistributed income has gone into paying the massive and obscene executive salaries that we are discussing in this blog.

For workers, the problem is that they rely on real wages growth to fund consumption growth and without it they borrow or the economy goes into recession. The former is what happened around the world in the lead up to the crisis (and caused the crisis).

The latter is more or less what is happening now.

One of the essential changes that needs to happen to ensure that another bout of financial instability doesn’t hit soon is that real wages have to grow in proportion with productivity growth – exactly the reverse of what is happening now.

That will require a fundamental revision of the way executive pay is determined and significantly reduced payout outcomes for the bosses.

The latest Australian data from the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI), the body that “provides independent research and advice to assist its member superannuation funds to manage environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) investment risk”, shows that:

– Almost one third of ASX100 CEOs (25 of 83) received bonuses equal to 80%, or more, of their potential maximum payout … executive bonuses in large companies are better described as “variable fixed pay”, rather than genuinely at-risk performance pay.

– Bonus persistence remained a feature in FY16 for ASX100 CEOs.

– The median bonus accrued for an ASX101-200 CEO rose almost 30% to $486,000 …

– Median … ASX100 CEO fixed pay … rose … 4.4% …

– Average realised pay (cash payments plus the value of vested equity) was again significantly higher than average reported pay …

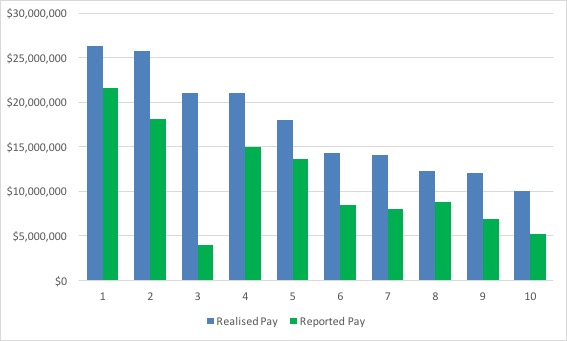

The following graph shows the gap between the reported pay and realised pay for the top 10 CEO earners. It is clear that there is a significant variation in what the companies report in their Annual Reports and the extra payments associated with cash payments on top.

The ACSI had argued in an earlier Report that:

These figures suggest that the existing requirements for reporting executive pay may significantly understate the rewards received in a given year. Statutory reporting is, perhaps, disclosing only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the wealth accruing to senior executives …

In its current report, ACSI say that:

The prevalence of CEO bonuses at consistently high levels raises serious questions about the way performance hurdles are being designed and applied. The fact that only 18 CEOs received bonuses below 50% of maximum indicates that they bear little relation to performance in many companies.

Which goes to heart of the justifications given out by boards of these companies that they have to pay the high salaries to get the best to do the best.

In fact, these exorbitant bonuses which come out of incomes redistributed from workers and the price gouging these companies engage in, “bear little relation to performance in many companies”.

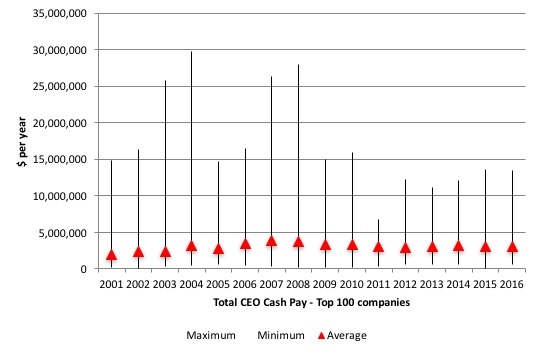

The next graph shows the average total CEO Cash Pay in the Top 100 companies (red triangles) and the maximum and minimum values for each year (indicated by the vertical lines).

The ACSI define the total cash pay as “fixed pay, cash bonuses and accrual of entitlements”, so more or less what an average worker might receive each year (the bonuses if they are lucky).

There is considerable disparity within the ranks of the CEOs (from max to min). There are some sensationally large salaries and some rather modest ones (in relative terms).

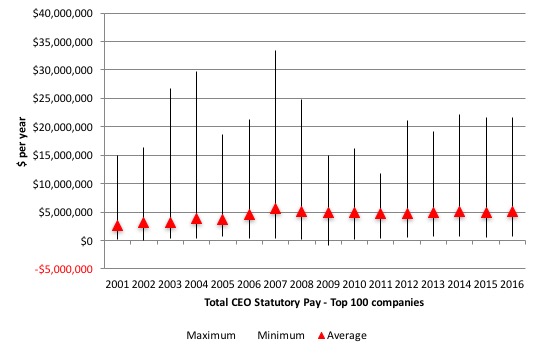

The next graph shows the average total CEO Statutory Pay in the Top 100 companies (red triangles) and the maximum and minimum values for each year (see accompanying table for actual dollar values).

The ACSI define statutory pay as “the total remuneration disclosed for a CEO in a company’s remuneration report, as required by Australian law. It therefore includes the value of share-based payments expensed under accounting standards”.

Don’t be fooled by the different scale of the axes in each graph – the statutory pay is a huge step up on the total cash pay although clearly well below the ultimate realised earnings (as detailed in the first graph).

Comparisons with other workers

But all of that analysis doesn’t mean much unless there is some context.

The next graph shows the Ratio of CEO Statutory Pay to Total Average Weekly Earnings (blue line) and Total Average Weekly Full-time Earnings (red line) from 2001 to 2014.

The ratio for the former started at 76.2 in 2001, peaked at 123.1 in 2007 at the height of the ‘greed is good’ frenzy and is now back to 85.2 and is rising again.

The ratio for the latter started at 58.6 in 2001, peaked at 93.7 in 2007 and is now back to 62.5 but it is also rising again.

These differentials are always justified by the conservatives and the business lobby as being essential to attract top quality executives. But then we know that company performance is not closely linked at times to the pay that the CEOs get, which puts a hole in that argument.

When the 2013 data was released on September 18, 2014, an accompanying press report – Pay for Australian CEOs is down, but it’s still too high said:

The boom that lit the fuse of the global crisis then overwhelmed commonsense and decency … Pay was out of control at that time in almost every way. Short-term bonus hurdles were too low, shares were vesting too quickly and on terms that were too generous, and termination payments were too big.

Company leaders offered various excuses, all of them lame.

This is the ‘greed is good’ frenzy that was associated with the total failure of the financial market and associated labour markets to self-regulate along the lines that the mainstream economics and finance textbooks claimed.

The UK-based High Pay Centre released its own study with CIPD earlier this month (August 3, 2017) – CIPD/High Pay Centre survey of FTSE100 CEO pay packages 2016 – which showed that several CEOs received pay rises despite major failings in their companies.

For example:

Mark Cutifani, CEO of AngloAmerican, saw his pay package rise by half a million to £4.0 million despite the number

of fatalities among the workforce increasing to 11 fatalities, compared with six last year.At BHP plc, the CEO received no short-term incentive because of the collapse of the Samarco dam.

One notable jump in CEO remuneration was Arnold Donald’s of Carnival plc. He earned just over £22 million in 2016 (from £6 million in 2015), the year in which Carnival was ordered to pay £32 million in penalty charges relating to its deliberate pollution of the seas and intentional acts to cover it up. This is the largest-ever criminal penalty involving deliberate vessel pollution.

This reinforces earlier work by CIPD report in Britain that has found the idea that CEO salaries a market determined is ridiculous. There is very limited scrutiny by shareholders, and company boards boards are bullied or cajoled by celebrity CEOs who reward compliance with personal gain.

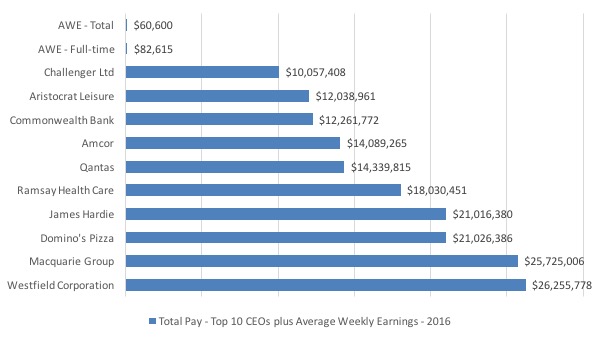

The next graph shows the salaries of the Top 10 CEOs in Australia compared to Average Weekly Earnings (Full-time) and Average Weekly Earnings (Total) for 2016.

The question is what does a person who runs a shopping centre empire contribute to society that is worth more than $A26 million a year relative to what an average workers contributes who only gets $A60,600 per year?

The question is unanswerable using any logic that is based on societal well-being, fairness, or decency.

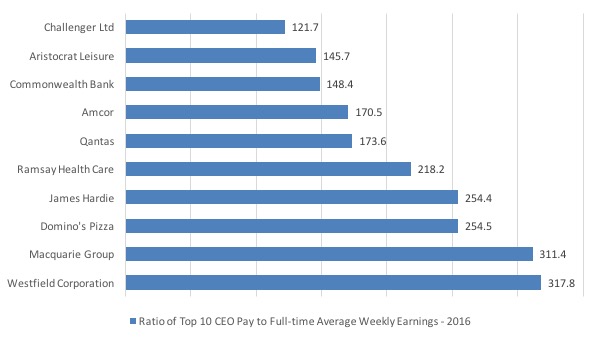

The next graph shows the pay ratios of the Top 10 CEOs in Australia compared to Average Weekly Earnings (Full-time).

I have reported elsewhere that the growth in the Wage Price Index in Australia is at record lows (for several successive quarters).

Please read my blog – Australia – real wages growth zero and the rip-off of workers continues – for more discussion on this point.

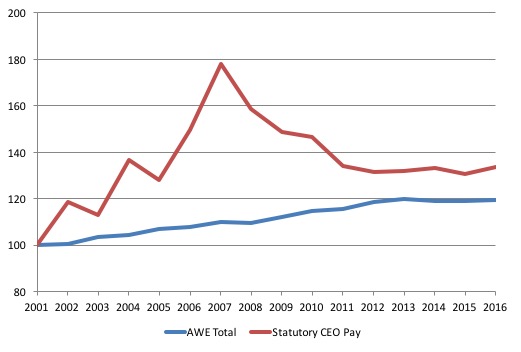

The following graph shows the movement in Average Weekly Earnings (blue line) and Statutory CEO pay (red line) both indexed to 100 in 2001. The data is also deflated using the Consumer Price Index, so reflects real growth.

I also use Average Weekly Total Earnings (which provides some measure of the shift towards part-time work) and a better indicator of the central tendency in the labour market.

Real Average Weekly Earnings Total Earnings (annualised) have grown by just 19.6 per cent since 2001 (up to 2016), while Statutory CEO Pay in Australia has grown by 33.6 per cent (up to 2016).

Of course, the CEO real pay exploded in the financial market frenzy before the crisis and by 2007 their real pay had risen by 77 per cent since 2001, compared to the average worker’s real wage rise of 11.2 per cent over the same period.

Since 2012, CEO real pay has risen by 1.7 per cent compared to real AWE 0.9 percent.

Between 2015 and 2016, CEO real pay rose by 2.1 per cent while real AWE rose by just 0.5 per cent.

The more recent period will see real earnings growth for average workers hovering around zero (if not negative) while CEO pay continues to growth in real terms.

Conclusion

There is a stream of research being published that demonstrates how fractured modern (financial) capitalism has become. In the post Second World War II period, the Cold War warriors in the West lampooned communism on the basis that the capitalist dream was spreading its rewards to the workers as well as to the owners of the capital.

The full employment consensus that emerged in that period, mediated by Social Democratic governments, achieved both productivity and real wage growth and more or less comprehensive Welfare States, which raised the material living standards of workers rapidly. At least, in the developed world.

There was also a sense that the regulative environment and cultural overtones had kept the capitalist class in check in terms of their share of the pie.

Of course, there was also a sense that the exploitation of workers in poorer countries in Asia, Latin America, Africa and elsewhere was increasing to allow the West to satisfy the demands of more organised workers in the advanced nations for better living standards.

With the abandonment of the full employment consensus, variously, around the mid 1970s and beyond (depending on the nation), and the emergence of Monetarism and its micro-economic manifestation (privatisation, deregulation, etc), that lull in worker exploitation in the advanced nations came to an end.

Capital found a way to co-opt the state to work in its favour more fully and abandon its role as a mediator in the class conflict, which up until then, following the end of the War, had helped workers improve working conditions, pay levels, and provided social wage benefits in the form of public education, public health, public transport and all rest of it.

It’s interesting that the Left have bought the myth that the state is no longer relevant or has the capacity to influence national economies in the face of globalisation and global financial flows.

But the state never went away. It is still as important as it ever was. It is just now, that it openly works in the interests of capital rather than acts as the mediator.

This ongoing CEO salary binge, even though it is clearly now often at the expense of their own companies well-being, is a sign that capitalism is once again getting ahead of itself.

We saw it at the end of the 19th century, which provoked the rise of trade unions and broad social movements designed to force elected governments to act more broadly in terms of the interests that it served.

These movements led to the Social Democratic era in the West. The lesson was that workers will only take so much and when their material living standards are so threatened, they retaliate and will not remain passive.

At some point, this neo-liberal era will be brought to an end by some similar type of worker reorganisation and uprising. I hope it comes within my own lifetime.

Thanks

And, thanks to all those who helped the organisers of the upcoming event at the British Labour Party. It was a tremendous effort from all of you to cover their expenses and I look forward to a good event in late September. I will make full details of my UK-European speaking tour in September and early October available soon.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Privatisations and anti-union laws plus the relative growth of the white collar financial service industry and the shrinking of the traditional blue collar, unionised manufacturing industry has marginalised the power of the average employee.

Its at this stage difficult to see where push back might come from. An increase in the share of wages as a share in National Income should benefit many business as employees are not only a cost of production but they are also consumers.

Will the best hope come from the election of a government that understands its fiscal capabilities and will use a Job Guarantee and the Public Service as a pacesetter for higher wages or will the union movement somehow work out how to engage and enlist non-unionised workers??

Wow average earnings of $60,600.

At best I’m making 50,000 (in a good year) with job insecurity (casual work and self employed)

That doesn’t reach the threshold to begin paying off my student loan. Then I wonder, what the point of an education was?

@Barri,

I can’t see the push coming soon but I can see it coming.

The youth are largely locked out of the housing market, forced to pay obscene rents and have insecure work. It’s only a matter of time before they begin organising.

In my view, the union movement has to reach out to these disenfranchised young Australians (many approaching 30 with job insecurity and lack of secure housing) and begin speaking the truth.

Governments choose the unemployment rate, as a society we choose what we make public goods, the government can ALWAYS meet payment obligations, it must spend so we can earn, every generation chooses their own level of taxation.

We then need to start massive stop work protests and cut the flow of income to capital until we get what we want.

Wow ! That’s not just a typical conclusion is it ?

Wonderful writing.

As most people did, I received a letter from Fahour explaining that due to tough circumstances, postal prices would rise to $1 and henceforth Aus Post could only guaranteed a six day delivery. However, for those who wanted, for an extra 30c, letters could be delivered within 3 days. In short – a 60c cent rise in postal cost for the same service, an increase of 85.7% and not a murmur from either government or opposition. Then we hear a few months later about the money being splashed around the “executives” by the board of Aus Post. Do any of these thieves have to answer for their decisions? OK so we know all about this. But what occurred to me is that we are now going through exactly what gave the US to Trump – stagnant wages, CEOs receiving pay that can be considered nothing less than theft and the shifting of resources to the top end – we pay 85.7% more for letter delivery while Aus Post board and Fahour and his cronies end up with obscene bank balances. So what the hell do ordinary people do about this? I suppose the best I can do I write to my Federal member who happens to be a Liberal.

‘The lesson was that workers will only take so much’

It seems to me that private debt has allowed this farce to continue for so long. Without the banks extending credit on steroids there would have been a backlash much earlier.

In the UK, the docility has bean breathtaking with people swallowing the Government guff that it is the fault of the ill and those unemployed -the media hammered this for the last 7 years.

Now that the Labour Party has moved Left (albeit with bogus , semi-neoliberal understandings of the monetary system) there are SOME signs of change.

I have just finished doing some research, and wanted to make sure I am understanding some things correctly.

According to yours and others work, if a government causes the money supply to increase without there being corresponding goods and services to match, this has the potential to increase inflation. Correct?

Is it not true also though, any private agent who profits from his dealings (with passive income or buy low sell high), is also increasing purchasing power without corresponding goods/services to match, and is thus potentially increasing inflation?

With these two scenarios, it would suggest to me that the ‘only’ way to prevent any increase in money supply (whether by public or private sector activity) from causing inflation is to ensure that that money is spent on investment in producing more goods and services (which must also have a certain % of that turned to investment). Would I have this correct?

Why is it then, we are claiming to have a free-will autonomous based system if everyone complains that either the govt, or the CEO’s, or the guy next to me is increasing purchasing power without backing, and yet its ok for me to do it with my house? If my house goes up in value and I take that profit and spend it on gambling, drugs, overseas holidays, cable tv, etc, which does nothing for investment, then how can I then have cause to complain about anyone else doing it?

In other words, it doesn’t matter from which side of the political spectrum you sit, you are the pot calling the kettle black when you complain of the other side increasing purchasing power without investing it. What am I missing here?

“Is it not true also though, any private agent who profits from his dealings (with passive income or buy low sell high), is also increasing purchasing power without corresponding goods/services to match, and is thus potentially increasing inflation?”

From what I know, no. Buying and selling by players in the market just moves buying power from one player to another — increasing one person’s power while decreasing another’s. AFAIK lending by private banks does increase the money supply, with a time limit, and subject to the private bank’s ability to service the borrower’s spending.

Given enough business activity, banks can net out the spending of their borrowers so as to commit less of their own money than the activity the borrowers create.

For a very rough kind of parallel, in the 16th century, Jakob Fugger’s bank collected a fee from the Vatican for conveying collection plate revenue from Sweden to Rome. The bank didn’t actually move the money. They could use the collection plate contributions to pay their own debts in Northern Europe, and pay the Vatican with the proceeds of the loans they’d made to borrowers in Italy. Much handier and less risky than trying to move gold and silver across Europe.

“From what I know, no. Buying and selling by players in the market just moves buying power from one player to another – increasing one person’s power while decreasing another’s.”

Thx Mel.

I wasn’t referring to simple spot exchanges.

To put it in context, I’ll refer to this link from the treasury dept

https://archive.treasury.gov.au/documents/1156/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=01_Brief_History.asp

where it says on capital gains tax and why it was introduced

“In 1985, based on equity grounds, it was argued that, ‘because real capital gains represent an increase in purchasing power similar to real increases in wages, salaries, interest or dividends, they should be included in any comprehensive definition of income’ (Australian Government 1985 page 77).”

So what I was referring to are all those elements in any exchange which result in some increase in purchasing power. If my house increases in value through no effort on my part, then is that not contributing to an increase in purchasing power?

Dingo, you start off very wrong- Bill Mitchell does not say that causing the ‘money supply’ to increase will cause inflation. Bill Mitchell is always very careful to point out that any increased spending can cause inflation, especially if the economy lacks the real resources to increase production in response to that spending. The ‘money supply’ has nothing to do with that- it is spending, which may or may not increase with whatever measure of the ‘money supply’ you want to use in any particular circumstance.

And then, as Mel points out, you seem to confuse ‘buying low and selling high’ within the private sector with increasing the amount of potential demand in an economy, which is wrong because it is better understood as transferring spending ability from the individual ‘buying high’ to the individual selling the asset at that time. Unless there is NEW spending power created which can happen through bank loans that create money for their duration, or through government spending.

And MMT is not really concerned about the ‘money supply’ or about preventing it from increasing. MMT recognizes that in the monetary systems we live in, the ‘money supply’ is primarily determined by the economy itself. If there is too much spending, and inflation results, MMT says tax more. Or spend less. Nothing to do with ‘money supply’.

Yes you are right: I have gone over some other posts and found the following:

“Inflation is a product of spending rather than build up of bank reserves. ”

“So it is not the monetary policy setting but rather the final spending in excess of productive capacity that causes inflation.”

and you said “If there is too much spending, and inflation results, MMT says tax more. Or spend less.”

So where does this final spending, in excess of productive capacity, come from? What enables one to be in a position to finally spend more than production? Does it come from profits? Does it come from Govt spending? Is anyone suggesting that before I get to spend in excess of productive capacity that it should be taxed out of my hands and reinvested in more production? (I’m not agreeing or disagreeing, I am trying to determine the objective)

Dingo, spending in excess of productive capacity could happen in a number of ways as far as I understand. The worst way I can think of is that productive capacity suddenly dropped, such as through a terrible drought affecting food production or some other supply side catastrophe. Not much policy can do to prevent inflation there except for trying to prevent the situation from occurring in the first place. As far as inflation caused by increased demand for a continuous supply? – that can happen whenever there is a downshift in the overall savings desires of the private sector, or an increase in demand from the government for production from the private sector. I don’t think MMT says these are easily predicted or easily dealt with, just that they can be. One thing Bill Mitchell points out is that usually, capitalist economies are more often constrained by lack of demand, not lack of supply side ability. Which seems correct when I look at the history of my own country (US) for the last 100+ years. Except for a few years with the OPEC oil thing and maybe towards the end of WW2.

Thx Jerry

“As far as inflation caused by increased demand for a continuous supply? – that can happen whenever there is a downshift in the overall savings desires of the private sector”

That is an interesting statement. Where does savings come from? Is it not true that savings can only come if income is higher than expenditure? Is it mathematically possible for every entity with a balance sheet to save all at the same time?

Someone else from the US said the following on his blog:

“Capitalists will rarely spend enough into the economy to provide for full employment because the profit motive is too strong. One could actually argue that the idea of “full employment” is at odds with the natural profit seeking goal of capitalism.”

I believe this was said in context of whether or not capitalists should be forced to reinvest profits toward more production. Hence the reason I posed a similar question on here.

This made me ponder the validity of any legislation which mandates for full employment and also the impact it must have on one of the main principles of our common law, i.e. the common law right to individual autonomy. This legislation (if aimed at the total populace) is at odds with this common law principle (and I do not say this in defense of capitalists either).

Jerry and Dingo, don’t forget about debt in this discussion. First, when you talk about saving, you need to be clear about whether you mean a flow of assets into savings or saving net of new debt. A sector can spend more than its overall income by taking on debt in excess of its saving. It was large increases in private sector debt that fueled the U.S. economy leading up to the great recession. It is also true that taking on debt in the private sector increases some measures of the money supply, so when you talk about money supply you have to qualify which measure you mean.

Based on the objective of full employment, I wanted to ask if we think that not only should everyone have some form of employment, but should we all be aiming to own our own homes also?

Do we believe from a mathematical perspective that both full employment and home ownership for every household unit is possible?

Dingo: This legislation (if aimed at the total populace) is at odds with this common law principle (and I do not say this in defense of capitalists either).

Well, the only way full employment can be at odds with individual autonomy is if the legislation mandates that capitalists employ everyone who wants to be employed. This is a morally bad thing. And I do say this in defense of the capitalists individual autonomy! 🙂 It is also foolish and unworkable, but that is not the MMT proposal – where the foundation of full employment is the JG, employment from the state. Of course this greatly increases individual autonomy – more than anything since the end of slavery.

Do we believe from a mathematical perspective that both full employment and home ownership for every household unit is possible?

Of course. Why not? In the unusual circumstance that every household unit wants to own a home, there is no obstacle to it in today’s societies. Why would one want to force individual household home-ownership on those who prefer to rent, or live in condominiums or communes or whatever?

To varying degrees, during the postwar era, the whole world tested such policies of full employment and enough affordable housing so that homelessness was thought of being of something in the past – and they were very successful. But then the dark age of economic understanding fell, and there was Full Employment Abandoned (hmm who wrote the book on that?).

It takes quite a lot of contortions, illogic and intellectual gymnastics to see government-organized full employment as infringing on individual autonomy etc. Which is not to say that people haven’t been paid to perform such circus tricks, and hypnotized many into believing them.

The job guarantee program is based on a so-called human right which is defined as the ‘right to work’ but then does not give the worker the right to define what work really is or means.

The legal definition of employment is:

“A species of contract by which one person agrees to perform a job, service or task for another, with or without remuneration although, as with all contracts at common law, some form of consideration must flow.”

If any job guarantee program enables one to develop, cultivate, and practice whatever skill or talent they so choose, whether motivated by money and property or not, and whether valuable or not from an economic perspective, and further does not force the same to bind any other legally as a result of practicing said skill, and as a result of said development, cultivation and practice, has their human needs met, then I’m all for it.

If however, a job guarantee program specifies that you may not define the meaning of work, but only an economist and/or politician/law maker may so define work, and as such you may be forced to employ a skill that only has value from an economic perspective, and further, you will be forced to hold others legally accountable as the means by which to express said skill in return for human needs, then I am against it because there is no personal autonomy. Personal autonomy starts and ends with the individuals ability to define work, value, and contribution to the community. It does not rest with anyone else.

However, in saying this, if your definition of work includes a goal to pursue private property and wealth, then it must by definition only have value from an economic perspective. One can not own economic wealth if they do not create economic wealth.

I shall explore this job guarantee program you speak of and see if it fits with individual autonomy.

Glad to see your reply. Gotta go very soon.

Quick answer. I think the MMTers would agree that the biggest scale single work program they mean was the US’s New Deal alphabet soup- the WPA, Harry Hopkins etc. Harry Hopkins spent more money than the US did on WWI! There is no question that the New Deal programs were much closer to your “enables one to develop . . .” model than the other one.

Second – an important point – ” valuable or not from an economic perspective” simply makes no real logical sense. The gubmint in paying the money for socially decided purposes using individuals’ skills defines “valuable from an economic perspective”. We live in monetary economies & money is a creature of the state. The money that the capitalists are all after is the money made valuable by the government, by government taxation and by government spending, like the WPA. Cartoon capitalists just want this socialism for the rich folks like them, only, so they can be permanent feudal aristocrats, doling out dimes and degrading jobs to the masses.

It was fascinating reading something Abba Lerner said which made me question why governments are so adverse to the idea of eliminating business cycles, implementing JG programs, and so forth.

Would we agree that if any government implemented a JG program and/or always mopped up surplus output, that the country itself would become extremely prosperous in relative terms (compared to other countries)?

Could this be what is actually feared, on account of the fact that it would create envy from other countries, create huge surges in migration, and so forth. It seems to me that if any country wishes to employ this model it is really only going to work if everyone does it.

Thoughts?