I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

European Commission forecasts – a denial of their only effective policy tool

In Greece, the national unemployment rate has been around (or higher) than 25 per cent since 2013 so it is little surprise that mortgage defaults has spiralled and people are selling of family heirlooms to wealth antique dealers in Switzerland to cover daily costs. A Geneva-based dealer told the Financial Times in June (Source) that “For buyers there are opportunities that only come along when there’s a real economic upheaval . . . in Greece it hasn’t happened since the second world war”. So the vultures are enriching themselves as a result of peoples’ misery. Its the market! No it isn’t. Its an incompetent government looking after themselves and allowing their citizens to go down the drain. Just yesterday, the Greeks have agreed to tougher foreclosure measures (as part of the bailouts) which will see impoverished Greeks lose their last vestige of dignity – their homes. And the latest European Commission – Autumn Economic Forecasts – (released November 5, 2015) portend a very sorry future for Greece and the Eurozone generally.

The wording of the Autum Forecast Report is an exercise in the denial-language of Groupthink.

We read that:

The growth outlook for the euro area is thus likely to remain modest over the forecast horizon. As the tailwinds fade, other factors will come to play a larger role in driving economic growth in 2016 and 2017. Monetary policy is set to remain highly accommodative and fiscal policy to remain broadly neutral.

The tailwinds are the “low oil prices, a relatively weak external value of the euro … [and] … policy support, in particular the ECB’s very accommodative monetary policy and a broadly neutral fiscal stance.”

So the fact that fiscal policy isn’t hacking into growth is now classified in Eurozone-speak as being supportive.

If you dig into the analysis, you will not be left with any confidence that growth will continue at the rates forecast (1.8 per cent in 2016 and 1.9 per cent in 2017 for the Euro-area as a whole).

Greece is predicted to remain in recession at least until 2017 and it will still have an unemployment rate of 24.4 per cent in 2017 – thanks go to the national leadership of Syriza for that!

But it will have an external surplus by 2017 (courtesy of the massive slump in imports) and its fiscal balance will come in under the Stability and Growth Pact thresholds and the primary fiscal balance (net of interest payments) will be in massive surplus.

A fine way to run a country.

Which brings me to the bias in the Autumn Forecasts. The whole policy process is based on an export-led growth strategy coupled with a suppression of domestic demand.

The modest growth downgrades are all down to the troubles in the so-called Emerging Economies and China. The full analysis notes that one bright spot is that:

The economic recovery in the US is expected to continue at a robust pace, supported by low energy prices, a waning fiscal drag, and a monetary policy that is still supportive.

But the EU elites cannot bring themselves to admit that with a more relaxed fiscal position helping the growth prospects in the US surely their own fiscal strategy needs a dramatic revision to also support higher domestic demand in the face of declining external demand.

The art of responsible policy management is to do the best you can with the factors that you control rather than rely on a host of other factors that you do not control – such as when the Emerging Economies are going to pick up or when China gets its domestic rebalancing act together.

By continuing to suppress the fiscal policy impact on domestic demand through the rigid application of fiscal rules, the EU is tying one of its ‘control’ levers behind its back.

Apparently, active fiscal policy in the EU these days can only be exercised in one direction – austerity.

The Autumn Forecasts state that continued “fiscal consolidation is still forecast in the EU” (that is, austerity) at a time when growth is stalling.

Hardly inspiring leadership.

It is also clear that private consumption will taper off as “real disposable incomes should grow more slowly than this year”. The predictions suggest that the income effect on consumption will not be huge because “because household saving rates are expected to decline”, in part due to the low interest rate environment.

The EU predicts that growth in capital formation (which has been abysmal for some years now) will “strengthen gradually … but less than in past recoveries”.

I did a simple calculation and for the Eurozone (19 nations), capital formation has fallen by 16 per cent since the March-quarter 2008 (up to June-quarter 2015). The investment to GDP ratio has declined by around 3 percentage points.

Firms will not invest when the sales environment is weak.

This brings into question the bias towards monetary policy which is building the balance sheet of the ECB at a substantial rate but for which little fruit will be forthcoming.

Various commentators thought that the quantitative easing program would give the banks more money to lend and that would stimulate investment.

It was a myth that was dispelled in the 1990s when the Bank of Japan fell for the same myth that pervades the university macroeconomics textbooks.

Please read my early 2009 blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

Banks do not loan out reserves! Investment is weak in the Eurozone because firms do not see any substantial policy changes or other circumstances that will lift real GDP growth and start to strain their existing productive capacity.

Furthermore, the most recent external data released by ECB (October 20, 2015) – Euro area monthly balance of payments – August 2015 – shows that:

… combined direct and portfolio investment recorded an increase of €9 billion in assets and a decrease of €24 billion in liabilities.

But decomposing that into its constituent parts provides a quite stunning picture of what is happening.

The Report shows that direct investment has been flat for the more than a year now, while since April 2015, portfolio investment has accelerated sharply.

We learn that:

… euro area residents made net acquisitions of foreign securities in a total amount of €9 billion, owing to net purchases of long-term (€18 billion) and short-term debt securities (€2 billion), which were partly offset by net sales of equity (€11 billion).

As a proportion of GDP, Portfolio investment has gone from zero per cent in April 2015 to nearly 3 per cent in August 2015 – a quite stunning shift.

What does that mean?

It means that Euro area residents are sending their savings abroad and buying foreign financial assets. It has three consequences. First, the savings are not being recycled into capital formation within Europe, which suppresses domestic demand now and maintains elevated unemployment rates.

Second, it undermines future potential growth by suppressing the growth in productive capacity.

Third, if foreign investment markets start to weaken then the feedback effects on domestic spending will worsen.

Moreover, the financial capital outflows reduced the exchange rate (euro) from May 2014 to March 2015 but since then there has been no substantial depreciation (against the USD or the other major currencies – particularly the trading partners of the Eurozone).

The Euro area is only slightly more competitive in international markets now than what it was in 2012 (see Bank of International Settlements Real Effective Exchange Rate series).

So the trade boost that QE might have fostered through the ‘savings exports’ will not be sufficient to drive growth in the Eurozone at levels necessary to bring the excessively-high unemployment rates down.

The Europeans might care to reflect on the US experience which is summarised (not without imperfections) in the Wall Street Journal article (October 28, 2015) – What U.S. Growth Looks Like Without the Government Spending Slowdown.

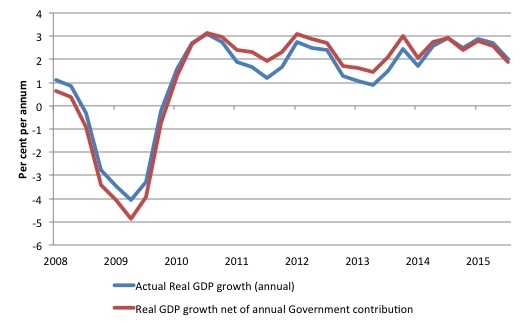

The article shows how fiscal policy stimulus saved the US economy. They produced a neat graph which compares the actual real GDP growth with the counterfactual of what it would have been if we take the government contribution out.

I reproduce it below (not as pretty as their graph) using the BEA National Accounts data (I could have copied their graph but I wanted to check on how they did it to make sure I understood what they were assuming).

They simply took the contribution of total US government consumption and investment spending out of the actual real GDP growth rate (blue line) and compared that with the actual rate of real GDP growth (red line).

It is, in fact, a crude exercise.

They summarised the results as:

The drag was most pronounced in 2010 and 2013. It came after federal stimulus spending expired and was replaced by spending cuts. At the same time, state and local governments were feeling the full effect of lower postrecession revenues.

The drag lessened somewhat over the past year to about a 0.5 percentage point. That coincides with a federal budget agreement that blunted the impact of automatic spending cuts known as the sequester. The level of government spending has begun to rise again, but it’s still growing at slower pace than the rest of the economy.

But in fact the government contribution positive or negative is likely to be significantly understated because it ignores the effects of the expenditure multiplier.

Please read my blog – Spending multipliers – for more discussion on this point.

The increased government net spending did not just have an impact effect. By saving jobs and incomes it also stimulated private consumption spending somewhat and that, in turn, stimulated further real GDP growth.

So some of the government effect is embedded in the private household consumption effect. Some of the spending was also lost to imports but with a positive multiplier above unity (even the IMF agrees with that) the net effect of the government spending was in excess of the actual direct government contribution.

The WSJ, being what it is, considered the biases in their analysis might lean on overestimating the positive public sector impact due to the “uncertainty or potential tax burden mounting government deficits create for businesses and consumers.”

This is the Ricardian Equivalence type argument which all conservatives pull out of the bag when opposing fiscal deficits only to be overwhelmed by the power of the evidence.

Please read my blog – Pushing the fantasy barrow – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

It is almost incontrovertible that public fiscal stimulus was beneficial to growth when applied – even in the early days of the crisis in the Eurozone.

It is equally so that austerity has been a negative force.

The Eurozone remains wedded to the idea that its fortunes depend on world trade which is driven by factors they cannot control.

Staring them in the face is massive unemployment and fiscal policy which they can control. Their refusal to use the most effective growth policy tool available to them is a demonstration of their on-going failure.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Could someone please explain what is actually happening when Bill says “Euro area residents are sending their savings abroad and buying foreign financial assets,” given that Euros must stay in Eurozone banks. What is the trade balance, or whatever, that is driving this?

Dear dnm (at 2015/11/10 at 20:03)

It is quite simple – the exchange euros for the currencies in which they desire to accumulate foreign financial assets. The euros stay in Eurozone banks but the savings that were accumulated in euros previously are now denominated in whatever the relevant foreign assets are. The poor returns outlook on investment in the Eurozone is driving it.

best wishes

bill

“Various commentators thought that the quantitative easing program would give the banks more money to lend and that would stimulate investment.”

Not this ‘Friedmanite monetarist’?

“Strange though it may sound, monetary expansion could occur even if bank lending to the private sector were contracting.”

“In short, although the cash injected into the economy by the Bank of England’s quantitative easing may in the first instance be held by pension funds, insurance companies and other financial institutions, it soon passes to profitable companies with strong balance sheets and then to marginal businesses with weak balance sheets, and so on. The cash strains throughout the economy are eliminated, asset prices recover, and demand, output and employment all revive.”

Postkey

‘ …it soon passes to profitable companies with strong balance sheets…’

Buying shares in a profitable company does not provide that profitable company with one penny of additional investment. It is merely a transfer of funds and share ownership. Sure, assets are inflated (both stocks & property) – according to the B of E – but little finds its way into the desired long-term industrial investment. Of course the existing owners of assets appreciate the rise in the value of their assets.

So why should ‘demand, output etc revive’ significantly? Please explain.

And here in Oz we get the same neo-liberal clap-trap about budget repair, inter-gnerational debt and, well you know how it proceeds

https://theconversation.com/the-federal-budget-is-hard-to-fix-but-here-are-some-solutions-50309

This is what the ‘Friedmanite monetarist’ says.

{I would give you the site, but it appears that when I try to do that the comment never appears!}

“What is the likely sequence of events?

First, pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds and so on try to get rid of their excess money by purchasing more securities. Let us, for the sake of argument, say that they want to acquire more equities. To a large extent they are buying from other pension funds, insurance companies and so on, and the efforts of all market participants taken together to disembarrass themselves of the excess money seem self-cancelling and unavailing. To the extent that buyers and sellers are in a closed circuit, they cannot get rid of it by transactions between themselves. However, there is a way out. They all have an excess supply of money and an excess demand for equities, which will put upward pressure on equity prices. If equity prices rise sharply, the ratio of their money holdings to total assets will drop back to the desired level. Indeed, on the face of it a doubling of the stock market would mean (more or less) that the £150 billion of extra cash could be added to portfolios and yet leave UK financial institutions’ money-to-total-assets ratio unchanged.

Secondly, once the stock market starts to rise because of the process just described, companies find it easier to raise money by issuing new shares and bonds. At first, only strong companies have the credibility to embark on large-scale fund raising, but they can use their extra money to pay bills to weaker companies threatened with bankruptcy (and also perhaps to purchase land and subsidiaries from them). ”

This is how, according to the ‘Friedmanite monetarist’, QE is ‘supposed to work’!

I would need evidence that this policy is effective!