Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – July 4, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

One advantage of low inflation is that the central bank can better use balance sheet management techniques to control yields on public debt at certain targetted maturities.

The answer is True.

The “term structure” of interest rates, in general, refers to the relationship between fixed-income securities (public and private) of different maturities. Sometimes commentators will confine the concept to public bonds but that would be apparent from the context. Usually, the term structure takes into account public and private bonds/paper.

The yield curve is a graphical depiction of the term structure – so that the interest rates on bonds are graphed against their maturities (or terms).

The term structure of interest rates provides financial markets with a indication of likely movements in interest rates and expectations of the state of the economy.

If the term structure is normal such that short-term rates are lower than long-term rates fixed-income investors form the view that economic growth will be normal. Given this is associated with an expectation of some stable inflation over the medium- to longer-term, long maturity assets have higher yields to compensate for the risk.

Short-term assets are less prone to inflation risk because holders are repaid sooner.

When the term structure starts to flatten, fixed-income markets consider this to be a transition phase with short-term rates on the rise and long-term rates falling or stable. This usually occurs late in a growth cycle and accompanies the tightening of monetary policy as the central bank seeks to reduce inflationary expectations.

Finally, if a flat terms structure inverts, the short-rates are higher than the long-rates. This results after a period of central bank tightening which leads the financial markets to form the view that interest rates will decline in the future with longer-term yields being lower. When interest rates decrease, bond prices rise and yields fall.

The investment mentality is tricky in these situations because even though yields on long-term bonds are expected to fall investors will still purchase assets at those maturities because they anticipate a major slowdown (following the central bank tightening) and so want to get what yields they can in an environment of overall declining yields and sluggish economic growth.

So the term structure is conditioned in part by the inflationary expectations that are held in the private sector.

It is without doubt that the central bank can manipulate the yield curve at all maturities to determine yields on public bonds. If they want to guarantee a particular yield on say a 30-year government bond then all they have to do is stand ready to purchase (or sell) the volume that is required to stabilise the price of the bond consistent with that yield.

Remember bond prices and yields are inverse. A person who buys a fixed-income bond for $100 with a coupon (return) of 10 per cent will expect $10 per year while they hold the bond. If demand rises for this bond in secondary markets and pushes the price up to say $120, then the fixed coupon (10 per cent on $100 = $10) delivers a lower yield.

Now it is possible that a strategy to fix yields on public bonds at all maturities would require the central bank to own all the debt (or most of it). This would occur if the targeted yields were not consistent with the private market expectations about future values of the short-term interest rate.

If the private markets considered that the central bank would stark hiking rates then they would decline to buy at the fixed (controlled) yield because they would expect long-term bond prices to fall overall and yields to rise.

So given the current monetary policy emphasis on controlling inflation, in a period of high inflation, private markets would hold the view that the yields on fixed income assets would rise and so the central bank would have to purchase all the issue to hit its targeted yield.

In this case, while the central bank could via large-scale purchases control the yield on the particular asset, it is likely that the yield on that asset would become dislocated from the term structure (if they were only controlling one maturity) and private rates or private rates (if they were controlling all public bond yields).

So the private and public interest rate structure could become separated. While some would say this would mean that the central bank loses the ability to influence private spending via monetary policy changes, the reality is that the economic consequences of such a situation would be unclear and depend on other factors such as expectations of future movements in aggregate demand, to name one important influence.

Question 2:

Adopting a fiscal rule that requires the government maintain a fiscal balance of zero at all times means that the fiscal outcome is insulated from the impact of the automatic stabilisers.

The answer is False.

The final fiscal outcome is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the fiscal balance is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the fiscal balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the fiscal balance is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the fiscal balance is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the fiscal balance back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the fiscal balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the fiscal balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the fiscal balance in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

The first point to always be clear about then is that the fiscal balance is not determined by the government. Its discretionary policy stance certainly is an influence but the final outcome will reflect non-government spending decisions. In other words, the concept of a fiscal rule – where the government can set a desired balance (in the case of the question – zero) and achieve that at all times is fraught.

It is likely that in attempting to achieve a balanced fiscal position, the government will set its discretionary policy settings counter to the best interests of the economy – either too contractionary or too expansionary.

If there was a balanced fiscal rule and private spending fell dramatically then the automatic stabilisers would push the fiscal balance into the direction of deficit. The final outcome would depend on net exports and whether the private sector was saving overall or not. Assume, that net exports were in deficit (typical case) and private saving overall was positive. Then private spending declines.

In this case, the actual fiscal outcome would be a deficit equal to the sum of the other two balances.

Then in attempting to apply the fiscal rule, the discretionary component of the fiscal balance would have to contract. This contraction would further reduce aggregate demand and the automatic stabilisers (loss of tax revenue and increased welfare payments) would be working against the discretionary policy choice.

In that case, the application of the fiscal rule would be undermining production and employment and probably not succeeding in getting the fiscal outcome into balance.

But every time a discretionary policy change was made the impact on aggregate demand and hence production would then trigger the automatic stabilisers via the income changes to work in the opposite direction to the discretionary policy shift.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 3:

Only one of the following propositions is possible (with all balances expressed as a per cent of GDP):

- A nation can run an external deficit and equal government surplus while the private domestic sector is saving overall.

- A nation can run an external deficit and equal government surplus while the private domestic sector is dis-saving overall.

- A nation can run an external deficit and a larger government surplus while the private domestic sector is saving overall.

- None of the above are possible as they all defy the sectoral balances accounting identity.

The second option – “A nation can run an external deficit and equal government surplus while the private domestic sector is dis-saving overall” – is the only one possible as a result of national acccounting conventions.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

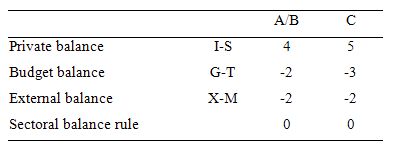

The following Table represents the three options in percent of GDP terms. To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

The first two possibilities we might call A and B:

A: A nation can run an external deficit and equal government surplus while the private domestic sector is saving overall.

B: A nation can run an external deficit and equal government surplus while the private domestic sector is dis-saving overall.

So Option A says the private domestic sector is saving overall, whereas Option B say the private domestic sector is dis-saving (and going into increasing indebtedness). These options are captured in the first column of the Table. So the arithmetic example depicts an external sector deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and an offsetting fiscal surplus of 2 per cent of GDP.

You can see that the private sector balance is positive (that is, the sector is spending more than they are earning – Investment is greater than Saving – and has to be equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

Given that the only proposition that can be true is:

B: A nation can run an external deficit and equal government surplus while the private domestic sector is dis-saving overall.

Column 2 in the Table captures Option C:

C: A nation can run an external deficit and a larger government surplus while the private domestic sector is saving overall.

So the current account deficit is equal to 2 per cent of GDP while the surplus is now larger at 3 per cent of GDP. You can see that the private domestic deficit rises to 5 per cent of GDP to satisfy the accounting rule that the balances sum to zero.

The final option available is:

D: None of the above are possible as they all defy the sectoral balances accounting identity.

It cannot be true because as the Table data shows the rule that the sectoral balances add to zero because they are an accounting identity is satisfied in both cases.

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

It always happens when I click on a blog within a blog for further reading it takes me around the world and back again and 8 hours have disappeared as I click on another link and another and another within each blog. My wifes going to divorce me. She says I love learning about central banking and money creation more than her.

Q3. What I think would be a very good post in the future would be if someone did a comparison of all of the major countries past and present. That shows that defcit spending has not been enough in all of these countries since 1979. Like an interactive world map. Click on a country and it shows full employment and what the defict was from 1945-1980 and then what it looks like between 1980 -2015 in comparison. Along with other things that show that monetary policy has not worked in an interactive form when you compare it with fiscal policy.

Would you not be far off the mark considering population growth and other factors. If you took an average of deficit sizes for the UK between 1950- 1980. You could then say close to this average is the minimum size the defcit should be for the UK to support full employment moving forward ?

I also found the bath anology very helpful to improve my understanding of stocks and flows and the sectoral balances. Even though I still think I’m 30% away from fully understanding them.