Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – June 20, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Assume inflation is stable, there is excess productive capacity, and the central bank maintains its current monetary policy setting. It is then true that if government spending increases by $X dollars and private investment and exports are unchanged then nominal income will continue growing until the sum of taxation revenue, import spending and household saving rises by $X dollars.

The answer is True.

This question relates to the concept of a spending multiplier and the relationship between spending injections and spending leakages.

We have made the question easy by assuming that only government spending changes (exogenously) in period one and then remains unchanged after that.

Aggregate demand drives output which then generates incomes (via payments to the productive inputs). Accordingly, what is spent will generate income in that period which is available for use. The uses are further consumption; paying taxes and/or buying imports.

We consider imports as a separate category (even though they reflect consumption, investment and government spending decisions) because they constitute spending which does not recycle back into the production process. They are thus considered to be “leakages” from the expenditure system.

So if for every dollar produced and paid out as income, if the economy imports around 20 cents in the dollar, then only 80 cents is available within the system for spending in subsequent periods excluding taxation considerations.

However there are two other “leakages” which arise from domestic sources – saving and taxation. Take taxation first. When income is produced, the households end up with less than they are paid out in gross terms because the government levies a tax. So the income concept available for subsequent spending is called disposable income (Yd).

To keep it simple, imagine a proportional tax of 20 cents in the dollar is levied, so if $100 of income is generated, $20 goes to taxation and Yd is $80 (what is left). So taxation (T) is a “leakage” from the expenditure system in the same way as imports are.

Finally consider saving. Consumers make decisions to spend a proportion of their disposable income. The amount of each dollar they spent at the margin (that is, how much of every extra dollar to they consume) is called the marginal propensity to consume. If that is 0.80 then they spent 80 cents in every dollar of disposable income.

So if total disposable income is $80 (after taxation of 20 cents in the dollar is collected) then consumption (C) will be 0.80 times $80 which is $64 and saving will be the residual – $26. Saving (S) is also a “leakage” from the expenditure system.

It is easy to see that for every $100 produced, the income that is generated and distributed results in $64 in consumption and $36 in leakages which do not cycle back into spending.

For income to remain at $100 in the next period the $36 has to be made up by what economists call “injections” which in these sorts of models comprise the sum of investment (I), government spending (G) and exports (X). The injections are seen as coming from “outside” the output-income generating process (they are called exogenous or autonomous expenditure variables).

For GDP to be stable injections have to equal leakages (this can be converted into growth terms to the same effect). The national accounting statements that we have discussed previous such that the government deficit (surplus) equals $-for-$ the non-government surplus (deficit) and those that decompose the non-government sector in the external and private domestic sectors is derived from these relationships.

So imagine there is a certain level of income being produced – its value is immaterial. Imagine that the central bank sees no inflation risk and so interest rates are stable as are exchange rates (these simplifications are to to eliminate unnecessary complexity).

The question then is: what would happen if government increased spending by, say, $100? This is the terrain of the multiplier. If aggregate demand increases drive higher output and income increases then the question is by how much?

The spending multiplier is defined as the change in real income that results from a dollar change in exogenous aggregate demand (so one of G, I or X). We could complicate this by having autonomous consumption as well but the principle is not altered.

So the starting point is to define the consumption relationship. The most simple is a proportional relationship to disposable income (Yd). So we might write it as C = c*Yd – where little c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) or the fraction of every dollar of disposable income consumed. We will use c = 0.8.

The * sign denotes multiplication. You can do this example in an spreadsheet if you like.

Our tax relationship is already defined above – so T = tY. The little t is the marginal tax rate which in this case is the proportional rate (assume it is 0.2). Note here taxes are taken out of total income (Y) which then defines disposable income.

So Yd = (1-t) times Y or Yd = (1-0.2)*Y = 0.8*Y

If imports (M) are 20 per cent of total income (Y) then the relationship is M = m*Y where little m is the marginal propensity to import or the economy will increase imports by 20 cents for every real GDP dollar produced.

If you understand all that then the explanation of the multiplier follows logically. Imagine that government spending went up by $100 and the change in real national income is $179. Then the multiplier is the ratio (denoted k) of the Change in Total Income to the Change in government spending.

Thus k = $179/$100 = 1.79.

This says that for every dollar the government spends total real GDP will rise by $1.79 after taking into account the leakages from taxation, saving and imports.

When we conduct this thought experiment we are assuming the other autonomous expenditure components (I and X) are unchanged.

But the important point is to understand why the process generates a multiplier value of 1.79.

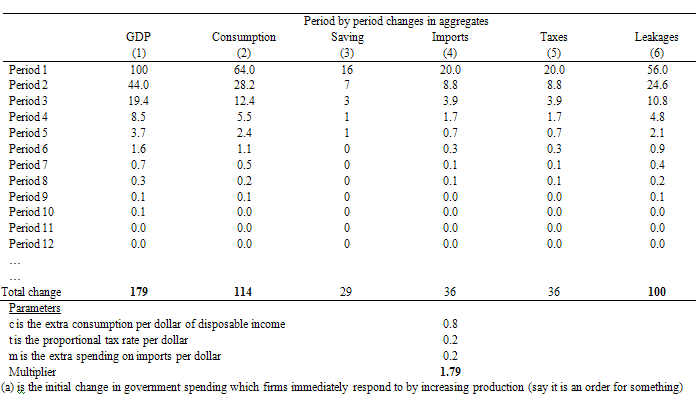

Here is a spreadsheet table I produced as a basis of the explanation. You might want to click it and then print it off if you are having trouble following the period by period flows.

So at the start of Period 1, the government increases spending by $100. The Table then traces out the changes that occur in the macroeconomic aggregates that follow this increase in spending (and “injection” of $100). The total change in real GDP (Column 1) will then tell us the multiplier value (although there is a simple formula that can compute it). The parameters which drive the individual flows are shown at the bottom of the table.

Note I have left out the full period adjustment – only showing up to Period 12. After that the adjustments are tiny until they peter out to zero.

Firms initially react to the $100 order from government at the beginning of the process of change. They increase output (assuming no change in inventories) and generate an extra $100 in income as a consequence which is the 100 change in GDP in Column [1].

The government taxes this income increase at 20 cents in the dollar (t = 0.20) and so disposable income only rises by $80 (Column 5).

There is a saying that one person’s income is another person’s expenditure and so the more the latter spends the more the former will receive and spend in turn – repeating the process.

Households spend 80 cents of every disposable dollar they receive which means that consumption rises by $64 in response to the rise in production/income. Households also save $16 of disposable income as a residual.

Imports also rise by $20 given that every dollar of GDP leads to a 20 cents increase imports (by assumption here) and this spending is lost from the spending stream in the next period.

So the initial rise in government spending has induced new consumption spending of $64. The workers who earned that income spend it and the production system responds. But remember $20 was lost from the spending stream so the second period spending increase is $44. Firms react and generate and extra $44 to meet the increase in aggregate demand.

And so the process continues with each period seeing a smaller and smaller induced spending effect (via consumption) because the leakages are draining the spending that gets recycled into increased production.

Eventually the process stops and income reaches its new “equilibrium” level in response to the step-increase of $100 in government spending. Note I haven’t show the total process in the Table and the final totals are the actual final totals.

If you check the total change in leakages (S + T + M) in Column (6) you see they equal $100 which matches the initial injection of government spending. The rule is that the multiplier process ends when the sum of the change in leakages matches the initial injection which started the process off.

You can also see that the initial injection of government spending ($100) stimulates an eventual rise in GDP of $179 (hence the multiplier of 1.79) and consumption has risen by 114, Saving by 29 and Imports by 36.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 2:

The expansionary impact of deficit spending on aggregate demand is lower when the government matches the deficit with debt-issuance because then excess reserves are drained and the purchasing power is taken out of the monetary system.

The answer is False.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

They claim that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a fiscal deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

The private domestic sector can save overall even if the government fiscal balance is in surplus as long as the external sector is adding to total demand in the economy.

The answer is False.

This is a question about the relative magnitude of the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance. The balances taken together always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

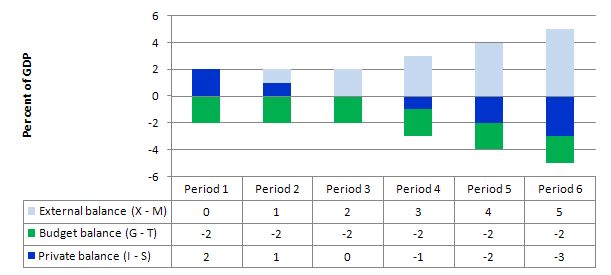

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. In each period I just held the fiscal balance at a constant surplus (2 per cent of GDP) (green bars). This is is artificial because as economic activity changes the automatic stabilisers would lead to endogenous changes in the fiscal balance. But we will just assume there is no change for simplicity. It doesn’t violate the logic.

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive – that is net addition to spending which would increase output and national income.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are decreasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow. So the question is what are the relative magnitudes of the external add and the fiscal balance subtract from income?

In Period 1, there is an external balance (X – M = 0) and then for each subsequent period the external balance goes into surplus incrementing by 1 per cent of GDP each period (light-blue bars).

You can see that in the first two periods, private domestic saving is negative, then as the demand injection from the external surplus offsets the fiscal drag arising from the fiscal surplus, the private domestic sector breakeven (spending as much as they earn, so I – S = 0). Then the demand add overall arising from the net positions of the external and public sectors is positive and the income growth would allow the private sector to save. That is increasingly so as the net demand add increases with the increasing external surplus.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

These sectoral balances are doing my head in and I’ve read them 1000 times.

Every time I think I’ve got it, it changes.

Half the time it sounds as if they are broken down to fit in with theory rather than what they are actually telling us.

I’m told over and over again that if the currency flows of the private sector are in surplus this means they are earning more than they take in and have a surplus of currency. Which means they can save.

And then if the private sector currency flows are in deficit they are either using their savings or borrowing. To meet demand or pay their taxes.

Then today it is said that remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning ?????

After the financial crash with huge surpluses ( sectoral balance graph UK) the private sector were certainly not spending more than they were earning.

Then this nugget – (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus. How can a deficit be a surplus if it is less than zero it must be a deficit. I've looked at 2000 sectoral balance graphs to try and understand them and never has a minus figure shown up as a surplus on the graph ?

Also, time and time again I am told exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit. So having a trade surplus must be a bad thing because we are exporting more than we import.

But today this gold mine – If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive. How can it be if exports are a cost ?

I give up….

One year I've spent on these damn things. God knows how many I've looked at. Yet the rules change every month.

UK sectoral balnce graph below.

http://www.eoi.es/blogs/the-spanish-paradox/files/2015/04/Capture.png

(I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning

(G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus

Really ?

@Derek Henry, It sounds like you are pretty close to getting this actually. The sectoral balances is describing an accounting relation, and that means there are two sides to it. There is a real side where goods and services change hands and a financial side where those goods and services are paid for. This makes it possible to value the real goods and services changing hands. This answers this question,

“Also, time and time again I am told exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit. So having a trade surplus must be a bad thing because we are exporting more than we import.”, So the author of this statement is looking at the real side and pointing out that the country is working to produce goods and services for overseas. The hint is in the two mentions of the real side of the accounting relation.

On the other hand,

“If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive. How can it be if exports are a cost?”, is talking about the financial side. The exports earn income for exporters (which is likely to add to aggregate demand eventually). The sectoral balances show that a country can support a higher level of aggregate demand without needing to supplement this with a private sector deficit (meaning further in debt) or government deficit spending as the support for domestic incomes (largely GDP) comes from overseas trade. This is similar to how Germany is running their economy at present. Though Germany is far from fully employed and could spend more to improve their infrastructure one would think.

Hi Nic,

I’m not sure I have to be honest.

I thought they were just currency flows.

I need a 101 on sectoral balances but with graphs and start from scratch.

I think you need so much more information before you can take anything away from them. You can’t just look at them and see what is happening. Which is what I was hoping.

You need to know what stage employment is at within the cycle for example and so much more background information like have the automatic stabilisers kicked in or not . Before they can tell you anything.

It’s my own fault I thought you could just look at them and they would be informative. Yet, you need to know all the quarterly results of so many things in advance before you look at them.

I also thought the real side would match the financial side.

I’m understanding around 75% of everything else even though I’m self taught and never been to university. These damn graphs just confuse me so I’m not going to look at them for a long time.

Neil Wilson posts all the quarters on his blog as well and I’m still none the wiser even though I follow the comments. I think I missed out when they were explained early on and I missed all of that as I came to MMT late.

The answer given for Q3 (“false”) seems to be based on an incorrect understanding of the English language.

Either (a) The error may stem from interpreting “as long as” as meaning “whatever”.

However, the normal/correct meaning of “as long as” in this context is ‘provided that’, ‘providing that’ or ‘on condition that’.

Or (b) the error may stem from using the word “can” (indicating a possibility) as meaning “must” or “will” (a required outcome).

If we avoid these errors, it is illustrated in period 2 of the “explanation” that the correct answer to Q3 is TRUE.

In period 2 the private domestic sector has net savings (1% GDP), the government is in surplus (2% GDP) and net exports are positive (3% GDP).

This fully satisfies the requirements of the question:

I was fooled by question 3 because I did not read it carefully enough. For 3 to be true, the external addition to domestic demand would have to be greater that the government surplus to enable the domestic non-governmental sector to save, but this is not specified in the question. So the answer is false.

Dear Bill

Where you discuss the marginal propensity to consume, you state that the residual is 26, that is, 0.2 x 80. Surely, that must be a typo. It should have been 16. Or am missing something here?

Regards. James

Derek Henry

Just looking at whether or not a number is positive isn’t enough, you have to look at what it is actually measuring.

I is private investment and S is private saving, so (I – S) > 0 means saving is less than investment, so the private sector is net dis-saving; spending more than it is earning. That’s a deficit.

G is government spending and T is taxation, so (G – T) < 0 means taxation is greater than government spending, so the government is spending less than it is 'earning'. That's a surplus.

Thanks

Flim Flam man.

http://bankunderground.co.uk/2015/06/19/the-bank-of-england-enters-the-blogosphere/

Bank of England starts a blog

That should be interesting

I answered number 2 as true

Because surely the government issuing bonds serves to soak up money from the banking system. This is money spent on bonds that then cannot be spent on goods and services or wages.

Can someone explain why this is not so?

Hi Coming

Read the links Bill gives at the end of the answer.

I do that even if I get the question right.

It’s good practice