The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Denmark should abandon its euro peg

In my soon-to-be-published book on the Eurozone I examined the case of Denmark in some detail in the context of the evolution of the European Monetary System, the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), and the ratification process of the Treaty of Maastricht. Denmark was a participant in all the attempts to maintain fixed exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971. Further, while Denmark did not formally enter the monetary union by adopting the euro that doesn’t mean that they have maintained their currency independence. They chose instead to peg the Danish kroner against the euro (effectively continuing the ERM parities), which immediately meant that its central bank had to follow ECB monetary policy. Fiscal policy then became a passive player to ensure it didn’t exacerbate the peg parity and Denmark also bought into the Stability and Growth Pact fiscal rules. This meant that internal devaluation (wage cutting) was the only real counter-stabilisation option available to them when facing external imbalances and domestic recession. It hasn’t worked well as one would expect. In fact, the euro peg works against the interests of the Danish people, particularly low income workers prone to unemployment. Yet the nation has an obsession with maintaining it. Groupthink abounds. The correct policy strategy which would give the Danish government a wider range of policy tools to enhance the well-being of its people would be for Denmark to abandon its euro peg. It should do that virtually immediately.

There was an interesting Bloomberg Op Ed earlier this week (January 19, 2015) – Denmark Should Cut Loose From Euro.

It was reflecting on the decision by the SNB last week to break its short-term peg with the euro – effectively declaring that the Swiss franc was undervalued and that the SNB wanted to break free of ECB influence (through the peg).

There has been a lot of so-called contagion from that decision with many speculators going broke. One should have little sympathy for them – they play the game and lose – so what.

But one consequence of the decision has been the upward pressure on the Danish krone against the euro, which presumably is a reflection of the speculators betting that the Danmarks Nationalbank (the Danish central bank) might also be forced to break its peg with the euro too.

So buying Danish currency assets would be a good bet if the Danmarks Nationalbank bails out on the peg, given the rapid appreciation in the Swiss franc last week.

For the Danmarks Nationalbank, it lowered deposit interest rates to -0.2 per cent and the lending rate (to commercial banks) to 0.05 per cent, as a way of discouraging capital inflows.

It is also facing up to having to sell lots of krone if the ECB introduces QE this week, which means it would be building ever large euro-denominated currency reserves. Why? To maintain the peg.

The Bloomberg article notes that while this will challenge the Danmarks Nationalbank:

… maintaining the peg is an act of faith in Denmark.

The Op Ed suggests that:

The central bank should rethink its commitment. With a more flexible monetary policy, it could have done more to stimulate the economy since the global financial crisis, just as it could have prevented some of the overheating that took place in the years running up to the crisis.

To understand where Denmark is now some brief history is required.

Early Danish fixed exchange rate pretensions

In 1873, Denmark created a multinational currency experiment with Sweden when they formed the Scandinavian Currency Union (SCU). Norway joined two years later.

It was a monetary union based on gold where each nation created a common unit of currency in decimal form – the Scandinavian krona. The currencies of the member nations (gold coins and other silver and bronze tokens) were fixed against the price of gold and would remain freely exchangeable at parity for a period of eight years, whereupon the common currency unit would prevail.

Political developments undermined the system. For example, when Norway broke with Sweden in 1905, the Swedes limited convertibility. But the monetary instability associated with the onset of World War I, was the last straw. The formal arrangement was terminated in 1921.

The sort of dysfunctions that rendered the SCU unworkable in 1873 did not evaporate in an historical cloud. They remain in force today and the Eurozone malaise are a modern manifestation of why currency unions between disparate nations with fiscal constraints cannot deliver material prosperity.

Denmark joins Bretton Woods

Much later, Denmark was an active participant in the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system, which was effectively terminated when US President Nixon abandoned the convertibility of the US dollar into gold and floated the US currency.

In the wake of Nixon’s decision, the nations met in Washington to save the global currency arrangements. The – Smithsonian Agreement – which was signed in December 1971 in Washington in the aftermath of Nixon’s shock decision, effectively attempted to reinstate the Bretton Woods arrangements by retaining the peg with the US dollar (although the non-US currencies were required to revalue against the dollar).

Further, there was no US dollar gold convertibility retained. The US dollar became a fiat currency with no backing other than the fact that the US government deemed it the unit that one had to use to relinquish tax and other legal obligations within the US.

However, the large external balance imbalances (particularly the US current account deficits) were not resolved and there was no long-term plan to

Recall that the fixed exchange rate system was internally inconsistent. It required the US government to run large current account deficits to supply US dollars into the system because other nations used the US dollar as the dominant currency in international transactions. To expand trade more dollars were necessary.

In the 1950s, there had been an international shortage of US dollars available as nations recovered from the war and trade expanded.

But in the 1960s, the situation changed. Nations started to worry about the value of their growing US dollar reserve holdings and whether the US would continue to maintain gold convertibility. These fears led nations to increasingly exercise their right to convert their US dollar holdings into gold, which significantly reduced the stock of US-held gold reserves.

By the 1960s, a large quantity of gold reserves shifted from the US to Europe as a result of persistent US balance of payments deficits.

The only way out of the dilemma was for the US to raise its interest rates and attract the dollars back into investments in US-denominated financial assets. But this would push the US economy into recession, which was politically unpalatable.

It is important to note that the US balance of payments deficits were also a reflection of choices made by other nations. In the growth period after World War II, other nations demonstrated a strong desire to accumulate US dollar reserves, which required them to run external trade surpluses against the US.

The Smithsonian Agreement did nothing to alter these tensions and internal inconsistencies within the system. But the Europeans were intent on modifying the Smithsonian arrangements in their own eccentric way to reduce their internal currency fluctuations.

One can look back in history and see that in 1972, the European nations were providing a rehearsal to the idiocy that was revealed in the signing of the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992.

Denmark joins the doomed snake

After much too-ing and fro-ing (in typical European style), the EEC nations (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) proposed a more restricted system to the Smithsonian Agreement, principally that the bands (values) in which the European currencies could fluctuate against each other would be narrower while still preserving the wider Smithsonian band with the US dollar.

While not yet a member of the EEC (it would join on January 1, 1973), Denmark signed up to the so-called – Basel Accord – which was popularly known as the ‘snake in the tunnel’, as a way of salvaging the failed Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate arrangements within Europe.

The tunnel being the overall band that the European currencies could fluctuate within with respect to the US dollar and the snake being the narrow fluctuations permitted between each other.

The snake started slithering out of control a few months after the Basel Accord after the British floated the pound and withdrew from the arrangement in June 1972 after a period of massive instability in international currency markets.

The international currency crisis intensified in January 1973, when Italy was forced to partially float the lira (segmenting commercial transactions from the rest) to stem the capital outflow. A full float came on February 14, 1973 but the decision to partially float meant Italy had to quit the ‘snake’.

The crisis deepened in early March as the US dollar hit its revised lower limits against the other major currencies. The US dollar was freely floating and the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates had finally been terminated despite the efforts to salvage it under the Smithsonian Agreement.

The remaining Basel Accord partners (Benelux, Denmark, France, Germany and the Netherlands), however, chose to ignore the ‘sword of Damocles’, such was their fear of floating exchange rates, and on March 12, 1973, announced they would jointly float against the US dollar, effectively keeping the ‘snake’ (Basel Accord) but abandoning the ‘tunnel’ (the Smithsonian Agreement).

Norway and Sweden came into the arrangement but soon left (Sweden on August 28, 1977 and Norway on December 12, 1978) due to the unviable nature of the arrangement. The group was dominated by Germany and had were facing external deficits against that nation, which required them to implement domestic recessions to maintain the agreed parities – via interest rate hikes to attract capital away from Germany.

Not much has really changed has it?

Denmark joins the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM)

As the snake failed, the next ingenious plan (not!) was to introduce the European Monetary System (EMS) and the associated European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), which stumbled into life on March 13, 1979.

It soon became a Deutsche Mark zone with the German Bundesbank calling the shots.

While the Bundesbank’s primary focus was on price stability, it also continued to be jointly responsible under the EMS for exchange rate stability, which at times compromised its capacity to maintain its target growth in the domestic money supply.

For example, to stop the mark from breaching the upper value limit, the Bundesbank was often forced to sell marks usually in return for US dollars or other currencies. This pushed more marks into circulation, which the Bundesbank considered exposed the German economy to an excessive inflation risk.

I discuss the sordid detail of the EMS in this sequence of blogs:

- Options for Europe – Part 24

- Options for Europe – Part 25

- Options for Europe – Part 26

- Options for Europe – Part 27

The system was an abject failure but the next stop was to build it into the Treaty of Maastricht. Denmark was part of the whole disaster.

Then came the ratification process

The Treaty of Maastricht 1992 had to be ratified by the Member States of the European Community. Denmark was the first nation to go through the ratification process.

The rules in Denmark were that a national referendum had to be held, which unfortunately for the political elites meant the people would have their say directly on the EMU, vote by vote.

The Danish politicians and bureaucrats had been operating in their own cocoon, attending too many EMU working groups, Council meetings, IGC meetings and had become trapped in the neo-liberal Groupthink. As a result, they confidently set June 2, 1992, just four months after the Treaty was signed, as the referendum date.

The result was a disaster for the EMU proponents. There was a turnout of 82.9 per cent of eligible voters but only 49.3 per cent were in favour.

The result meant that under the existing rules, Denmark would scupper the whole show. The European Council came up with a plan to salvage the situation.

After some heavy negotiation, four major ‘opt-outs’ required for Danish support were agreed to by the Council.

Accordingly, Denmark did not have to participate in Stage III, which meant they did not have to surrender their currency sovereignty. After gaining these concessions and assuaging the public hostility towards the EMU, the Danish government held a new referendum on May 18, 1993 and achieved a turnout of 85.5 per cent with 56.8 per cent voting affirmative. Not a substantial ratification by any means.

Danish monetary policy a creature of the Eurozone from the inception

But the important point for today’s discussion is that Denmark retained its almost religious commitment to fixed exchange rates and once the Euro was introduced and the ECB created, Danish monetary policy became a creature of the Eurozone.

The only difference that would happen if Denmark was to join the Eurozone would be that the Danmarks Nationalbank would become part of the – Eurosystem – which is the monetary authority of the common currency and this would formally stop the bank from implementing an independent monetary policy.

But the peg essentially amounts to the same thing.

How does the peg work?

Monetary policy becomes devoted to maintaining the pegged value. The Danmarks Nationalbank maintains the parity by daily trading in the foreign exchange markets.

When there is downward pressure on the Danish krone (DKK) against the euro, the central bank will purchase DKK and sell euro. The opposite operations are performed if the DKK moves to the upper ceiling of the desired band against the euro.

The Danmarks Nationalbank does not systemically peg against other currencies.

The Danmarks Nationalbank interest rate replicates the rates set by the ECB because if there was a divergence, capital flows would go one way or another and upset the exchange rate parity. So Denmark is in no better situation than, say Greece, in this respect. It has to accept the ‘one-size-fits-all’ interest rate set by the ECB, irrespective of whether that rate is suitable for the local conditions in Denmark.

This arrangement is referred to as ‘shadowing’ the ECB Monetary Policy Committee interest rate decisions.

Effectively, Germany economic conditions dominate the ECB rate setting and the rest have to follow.

There can be variations around the ECB rates, given that Denmark is not formally part of the Eurozone and there were notable examples in 2002 when the Danmarks Nationalbank went alone to try to ward of recession.

There are some other differences between the Danmarks Nationalbank operations and the ECB, which I won’t go into (relating to overnight standing facilities and refinancing operations) as they are complex and not germane to the narrative here.

On the fiscal side, Denmark embraced the Eurozone austerity mantra wholeheartedly and while not formally part of the sanctioning mechanisms under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), Denmark still adopts the fiscal rules, to its detriment.

Has the peg been good for Denmark?

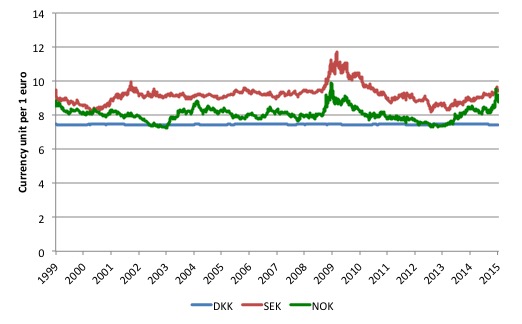

The following graph compares the evolution of the exchange rates against the euro (so how many local units are required per 1 euro) from January 1999 to January 20, 2015.

The currencies are the Danish krone (DKK), the Norwegian krone (NOK), and the Swedish krona (SEK). The effect of the peg has been to keep the DKK at about 7.4 per euro.

The non-pegged currencies (NOK and SEK) have been much more variable reacting to the different economic realities that the nations have faced in terms of their external sectors.

At the height of the crisis, the NOK and SEK depreciated against the euro given those nations are competitive advantage in net exports against the Member States of the Eurozone and Denmark, which as a result of the peg was effectively in the same boat as those Member States.

The impact of the peg is to eliminate arms of policy from playing a role – in this case monetary policy and the exchange rate.

What about real GDP growth?

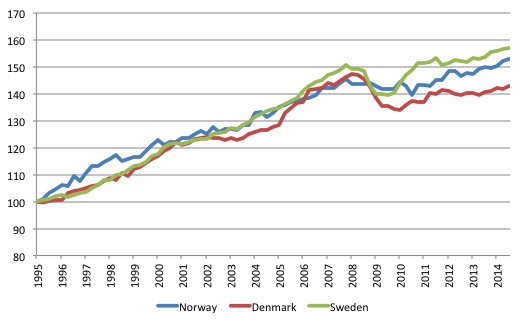

The following graph shows the evolution of real GDP since the first-quarter 1995 (indexed at 100 in that quarter) for Norway, Denmark and Sweden.

Once the Euro was introduced Denmark started to falter – with the early 2002 recession the precursor to what was to follow.

While the contraction in the Danish economy has not been as severe as say in Greece, it remains the case that after reaching a peak in the first-quarter 2008, real GDP is still below that peak 7 years later.

The other two Scandinavian nations clearly experienced a slowdown as a result of the GFC but have recovered much more strongly and moved beyond their December-quarter 2007 peaks within 8 quarters. Both the Swedish and Norwegian economies are around 4 percent larger than they were at the onset of the GFC.

The Danish economy remains 4 per cent smaller. In other words, the other non-euro Scandinavian economies broke clear of the shackles of the Eurozone malaise, while Denmark’s fortunes have been closely linked to the Eurozone.

The Bloomberg Op Ed argues that in the context of this poor economic performance that:

It’s not clear that the peg is a good idea now. Unlike Sweden, which has a floating currency and until 2010 had a more sensible monetary policy, Denmark hasn’t fully recovered from the global economic crisis.

The problem is that the “desirability of the peg, however, is beyond debate in political and economic policy circles”, which is another example of how the policy elites, supported by mainstream academic economists and think tanks maintain policy settings that work against the interests of the general population.

Yet, the majority of the population, even though severely affected by the ongoing crisis in Denmark are not able to discern that policy settings like the peg are directly causing their plight.

These people support policies that hurt them. Why? Ignorance!

The Bloomberg Op Ed argues that:

Whenever abandoning the peg is mentioned — which isn’t often — economists and politicians are almost offended. They regurgitate standard arguments without much substantive evaluation of the benefits and costs.

The neo-liberal Groupthink is alive and very active in that non-euro nation.

Conclusion

While many so-called Euro skeptics in Denmark argue on “nationalist or sentimental grounds” the progressive argument does not have to rely on any of those appeals. The socio-economic reality is that the Eurozone is locked into a cycle of stagnation – poor growth and crisis exposure – due to its flawed design. Denmark inherits the consequences of that design.

The result is sluggish income growth (and periodic cuts), higher unemployment and higher poverty rates. It is not a place any nation should aspire to.

The Bloomberg Op Ed says:

I don’t recall anyone arguing that it might be a good idea to abandon the peg, or to at least keep the option open, as an argument for voting no.

My Eurozone book to be published in early May 2015 provides a very detailed approach to why and how to abandon the euro, which also means the Danish could use the operational plan to increase prosperity as it abandons its peg.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

For ” experiment with Denmark” read “experiment with Sweden”.

Bill notes: Fixed now, Thanks Brian.

Dear Bill

Denmark has been running current-account surpluses. This means that the Danish krona is undervalued, but I don’t understand why that should be a hindrance for growth. It means that the Danes are living below their means, but why does an undervalued currency hinder economic growth? The disadvantage of having an undervalued currency is that too much growth takes place in the export sector, which produces for foreigners. Still, exports are part of GDP. A bloated export sector means lower consumption but not necessarily lower GDP.

Regards. James

Obviously the elites see some great advantage to fixing currencies, but what is it? It seems a rather expensive operation to pull off, first in setting up and maintaining it, and second in lost economic output/growth. That, plus the fact that any arrangement can be made to work (and perhaps even look pretty) in the short run, while in the long run, economic fundamentals always win out.

Is it that the elites are willing to pay these prices (continuously) simply to keep the hands of democratic government away from “their” money supply?

I’d say yes, plus they don’t stand to lose when arbitraging exploitation.

One question, what is MMT’s view on deadweight losses? I favor a land value tax (for other reasons) but surely there are some very bad taxes. Accepting we need a deficit in the UK for trade deficit and private surplus, perhaps it is better to reduce taxes and govt spending by the same amount of taxes more so transactions are encouraged.

As of today 1/22/2015, Denmark’s central bank (DCB) says their Euro peg is unshakable: (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2015-01-22/denmark-cuts-key-deposit-rate-to-minus-0-35-to-drive-down-krone.html.) The current price (as of Sunday, 948a CST), on 1/25/2015) EUR/DKK is 7.44588 with the peg that the DCB wants to support at 7.46038, according to Bloomberg report.

It seems to me that if the DCB coordinates it selling of the Kroner with the European Central Bank (ECB) buying it that might make the peg unshakable. At later date, the DCB sells its accumulation of Euro forex with ECB buying that and selling it Kroner’s with the DCB buying those back. hedge funds and small speculators would go broke selling EUR now, not selling DKK, if the DCB and ECB coordinate their forex activities to hold the EUR/DKK peg. Also, it will be interesting to see what happens this week to the exchange rate, not to mention, how the results of the Greek elections will add fuel to the forex fire.

To understand why there is a so great interest in maintaining the fixed currencies, one only has to look at the history: http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_euro#Relaunch

I quote: “France and the UK were opposed to German reunification, and attempted to influence the Soviet Union to stop it. However, in late 1989 France extracted German commitment to the Monetary Union in return for support for German reunification.”. Yes, this is right before the fall of the Berlin wall.

Furthermore, breaking the monetary union now would likely result in wild fluctuations between the “then-to-be-again” individual currencies. A situation that would then be not unlike that before WW1.

By maintaining commitment to the monetary union, they probably hope for a stabilization in the future, and if the problems in the southern-most states would be resolved, it might actually work.

Hope that it puts things in another perspective 😉