Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – November 15, 2014 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

During a recession, a government should use expansionary fiscal policy to restore trend real GDP growth if it wants to reduce unemployment rate.

The answer is False.

To see why, we might usefully construct a scenario that will explicate the options available to a government:

- Trend real GDP growth rate is 3 per cent annum.

- Labour productivity growth (that is, growth in real output per person employed) is growing at 2 per cent per annum. So as this grows less employment in required per unit of output.

- The labour force is growing by 1.5 per cent per annum. Growth in the labour force adds to the employment that has to be generated for unemployment to stay constant (or fall).

- The average working week is constant in hours. So firms are not making hours adjustments up or down with their existing workforce. Hours adjustments alter the relationship between real GDP growth and persons employed.

We can use this scenario to explore the different outcomes.

The trend rate of real GDP growth doesn’t relate to the labour market in any direct way. The late Arthur Okun is famous (among other things) for estimating the relationship that links the percentage deviation in real GDP growth from potential to the percentage change in the unemployment rate – the so-called Okun’s Law.

The algebra underlying this law can be manipulated to estimate the evolution of the unemployment rate based on real output forecasts.

From Okun, we can relate the major output and labour-force aggregates to form expectations about changes in the aggregate unemployment rate based on output growth rates. A series of accounting identities underpins Okun’s Law and helps us, in part, to understand why unemployment rates have risen.

Take the following output accounting statement:

(1) Y = LP*(1-UR)LH

where Y is real GDP, LP is labour productivity in persons (that is, real output per unit of labour), H is the average number of hours worked per period, UR is the aggregate unemployment rate, and L is the labour-force. So (1-UR) is the employment rate, by definition.

Equation (1) just tells us the obvious – that total output produced in a period is equal to total labour input [(1-UR)LH] times the amount of output each unit of labour input produces (LP).

Using some simple calculus you can convert Equation (1) into an approximate dynamic equation expressing percentage growth rates, which in turn, provides a simple benchmark to estimate, for given labour-force and labour productivity growth rates, the increase in output required to achieve a desired unemployment rate.

Accordingly, with small letters indicating percentage growth rates and assuming that the average number of hours worked per period is more or less constant, we get:

(2) y = lp + (1 – ur) + lf

Re-arranging Equation (2) to express it in a way that allows us to achieve our aim (re-arranging just means taking and adding things to both sides of the equation):

(3) ur = 1 + lp + lf – y

Equation (3) provides the approximate rule of thumb – if the unemployment rate is to remain constant, the rate of real output growth must equal the rate of growth in the labour-force plus the growth rate in labour productivity.

It is an approximate relationship because cyclical movements in labour productivity (changes in hoarding) and the labour-force participation rates can modify the relationships in the short-run. But it provides reasonable estimates of what happens when real output changes.

The sum of labour force and productivity growth rates is referred to as the required real GDP growth rate – required to keep the unemployment rate constant.

Remember that labour productivity growth (real GDP per person employed) reduces the need for labour for a given real GDP growth rate while labour force growth adds workers that have to be accommodated for by the real GDP growth (for a given productivity growth rate).

So in the example, the required real GDP growth rate is 3.5 per cent per annum and if policy only aspires to keep real GDP growth at its trend growth rate of 3 per cent annum, then the output gap that emerges is 0.5 per cent per annum.

The unemployment rate will rise by this much (give or take) and reflects the fact that real output growth is not strong enough to both absorb the new entrants into the labour market and offset the employment losses arising from labour productivity growth.

So the appropriate fiscal strategy does not relate to “trend output” but to the required real GDP growth rate given labour force and productivity growth. The two growth rates might be consistent but then they need not be. That lack of concordance makes the proposition false.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 2:

The current period is marked by private households increasing their saving ratios (from disposable income) and firms declining to invest. These trends indicate that fiscal deficits have to be higher to avoid further employment losses.

The answer is False.

The answer also relates to the sectoral balances framework outlined in detail above. When the private domestic sector decides to lift its saving ratio, we normally think of this in terms of households reducing consumption spending. However, it could also be evidenced by a drop in investment spending (building productive capacity).

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms layoff workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession. Interestingly, the attempts by households overall to increase their saving ratio may be thwarted because income losses cause loss of saving in aggregate – the is the Paradox of Thrift. While one household can easily increase its saving ratio through discipline, if all households try to do that then they will fail. This is an important statement about why macroeconomics is a separate field of study.

Typically, the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur – in the form of an expanding public deficit. The fiscal position of the government would be heading towards, into or into a larger deficit depending on the starting position as a result of the automatic stabilisers anyway.

So an intuitive reasoning suggests that a demand gap opens and the only way to stop the economy from contracting with employment losses if it the government fills the spending gap by expanding net spending (its deficit).

However, this would ignore the movements in the third sector – there is also an external sector. It is possible that at the same time that the households are reducing their consumption as an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public fiscal balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – May 22, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

If the external sector is accumulating financial claims on the local economy and the GDP growth rate is lower than the real interest rate, then the private domestic sector and the government sector can run surpluses without damaging employment growth.

The answer is False.

When the external sector is accumulating financial claims on the local economy it must mean the current account is in deficit – so the external balance is in deficit. Under these conditions it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the national accounting rules and income adjustments will always ensure that is the case.

The relationship between the rate of GDP growth and the real interest rate doesn’t alter this result and was included as superflous information to test the clarity of your understanding.

To understand this we need to begin with the national accounts which underpin the basic income-expenditure model that is at the heart of introductory macroeconomics. See the answer to Question 1 for the background conceptual development.

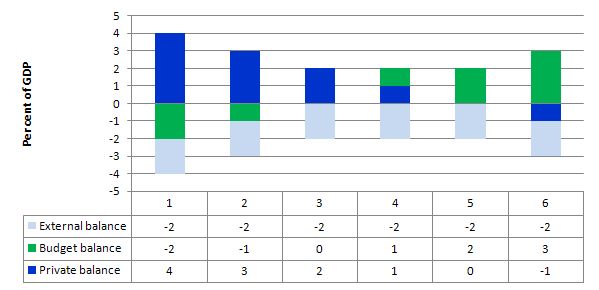

Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns).

State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns). This cannot be a sustainable growth strategy because eventually the private sector will collapse under the weight of its indebtedness and start to save. At that point the fiscal drag from the fiscal surpluses will reinforce the spending decline and the economy would go into recession.

State 2 shows that when the fiscal surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced.

State 3 is a fiscal balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country.

States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the fiscal balance goes into deficit – the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed fiscal positions into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough fiscal deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

The answer to Q2 is TRUE (not false) because there is an implicit ceteris paribus assumption regarding unmentioned factors. The question makes no mention of any change in exports or import propensity, so implicitly these are unchanged.

KongKing,

I would suggest regular readers would not make the same assumption about “unmentioned factors”. The question asked was if “fiscal deficits have to be higher”.

They don’t have to be higher if the external sector can be encouraged to spend more and thereby encourage unemployment.

Having said, that I’m still thinking about why I got Q1 wrong. The first time in a while! I sensed that the answer of TRUE was slightly too obvious and was therefore a trap but decided to stick with it anyway!

ps above should be “encourage employment” 🙂