I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Balanced budgets are rarely appropriate

The Fairfax press published the latest opinion piece from one of its economics editors (Ross Gittins) over the weekend (July 20, 2013) – The budget facts that Canberra isn’t telling you. If the stated facts are what Mr Gittins thinks apply to a sovereign economy such as Australia, then it is fortunate that Canberra is staying quiet. He claims that the fiscally prudent position is for governments to run a balanced budget on average every decade. He also says that the government doesn’t really have to do anything other than let the automatic stabilisers achieve that outcome once the structural settings are in place. The problem is that these sort of mindless fiscal rules are rarely going to achieve appropriate outcomes, when the latter is expressed in terms of full employment objectives and other real outcomes. In the current context, where there are major private sector balance sheet risks and an ongoing external deficit of around 3.5 per cent, the pursuit of a balanced budget would be an act of vandalism. Further, given the non-government spending dynamics, it is likely that continuous budget deficits will be required into the indefinite future.

There was a related article in the Money Section in the weekend Fairfax papers – We’re back in the black – which analysed (well noted) the recent saving behaviour of households. After reading this article, one would reasonably wonder what the hell Mr Gittins is writing about.

The Money article (written by one Penny Pryor) notes that to date, “Australia has been one of the few developed countries to avoid a residential property crash”. She speculates on whether another property boom is coming, most of which is unsubstantiated conjecture.

But the factual point the article makes is that there is a “new trend”:

… by Australian borrowers to pay off more of our homeloans … Ever since the GFC, we’ve changed our mindset and moved towards a savings mentality – we all feel that it’s better to save, or pay off debt, than buy that new wardrobe necessity or extravagance.

That is clearly evident in the data. The Australian National Accounts data shows that households are returning to more abstemious ways since the credit binge that marked the pre-crisis era.

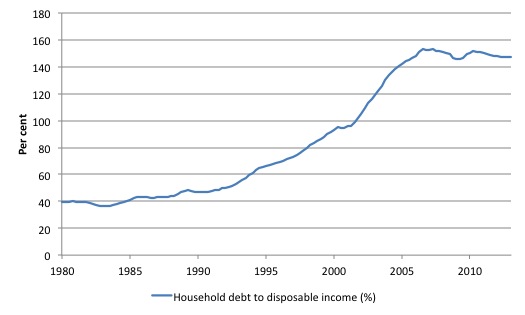

The following graph shows the evolution of the Household debt to Disposable Income ratio (%) in Australia from the March-quarter 1980 to the March-quarter 2013.

It is clear that the rapid escalation in the ratio during the neo-liberal period of financial market deregulation is now over and households, fearing rising unemployment and loss of homes (bankruptcy) are now saving and attempting to pay down the debt as indicated in the Money Article.

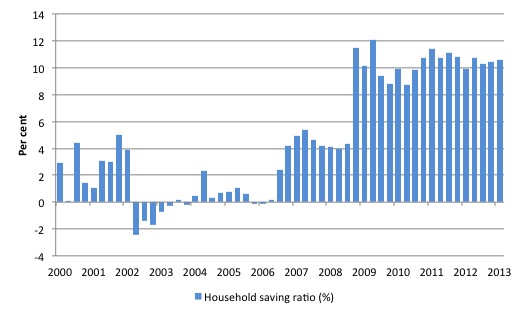

This is evidenced in the following graph, which shows the household saving ratio (% of disposable income) from 2000 to the current period. The household sector is now behaving very differently since the GFC rendered its balance sheet very precarious.

Prior to the crisis, households maintained very robust spending (including housing) by accumulating record levels of debt. As the crisis hit, it was only because the central bank reduced interest rates quickly, that there were not mass bankruptcies.

The household saving ratio was 10.6 per cent of disposable household income in the March-quarter 2013, nudging up from 10.4 per cent in the December-quarter 2012.

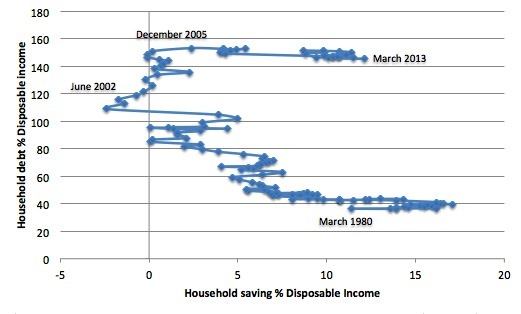

The following graph juxtaposes the movement in the Saving ratio (horizontal axis) with the Household debt to Disposable Income ratio (veritcal axis) from the March-quarter 1980 to the March-quarter 2013.

Th relationship shows that the household saving ratio returned to positive numbers in the December-quarter 2005 and the long-drawn out process of increasing it and holding it back around the 10 per cent level has been underway since.

The process of reducing debt levels will take many years and thus we should not expect a return to the credit-fuelled private sector expenditure growth that Australia witnessed in the pre-crisis period.

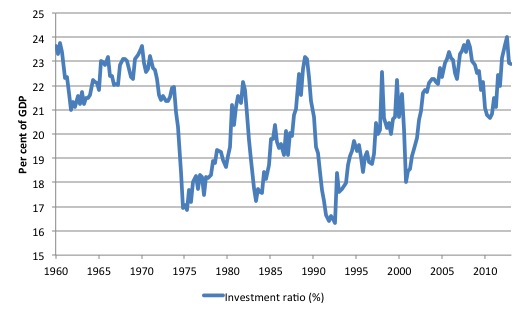

The next graph shows the evolution of the private sector investment ratio (total gross capital formation as a percent of GDP) for Australia since the March-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 2013. The cyclical volatility of the ratio is apparent.

Note also the steady rise from the lows associated with the very deep and prolonged 1991 recession and the more modest dip in 2009-10 as the GFC impacted. The most recent evidence shows that ratio has peaked and is now in decline again. So there is spending restraint coming from both sides of the private domestic sector – households and firms.

The households are largely trying to reduce their excessive debt levels, while the massive investment cycle associated with the record terms of trade (base metals etc) has ended.

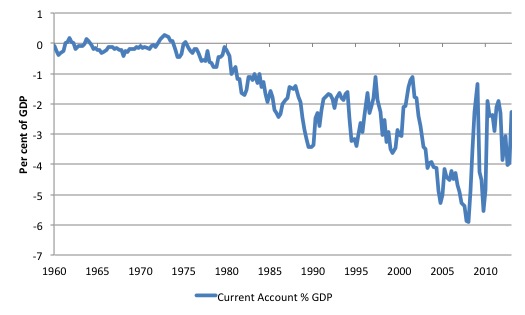

The final graph shows the Current Account balance as per cent of GDP from the March-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 2013. The current estimate in the Budget projections is for the balance to be 3.75 per cent of GDP in 2013-14 and 3.25 per cent in 2014-15. These estimates are probably not that far off what will actually happen.

Now this information pertains to the non-government sector of the economy.

The Australian economy can only lift its current well-below trend growth rate while households are maintaining the higher levels of saving (from disposable income), if net public spending, the private investment ratio and/or the current account ratio increases.

Clearly, the contribution from private investment is now fading. The expected maintenance of a current account deficit of around 3.75 per cent means that the aggregate demand drain arising from the external sector is expected to continue.

Which means that continued growth will require a much stronger net contribution (spending injection) from the government sector.

The problem is that if incomes start to drop and the households continue to pursue this saving proportion, aggregate demand will decline even further. The household sector is clearly carrying record levels of debt as a result of the credit binge leading up to the crisis and so we are unlikely to see a return to the low saving ratios that were evident in the period 2000 to 2005.

That means that government surpluses which were associated with the credit binge era, and were only made possible by the unsustainable credit binge are untenable in this new (old) climate.

A return to higher saving ratios is surely signalling a need for a return to more or less continuous budget deficits, given the likely evolution of the external sector.

The Government, which is obsessively restating its intention to return to surplus, needs to learn about these macroeconomic connections.

Mr Gittins also needs to learn that lesson. Which brings me to his article (briefly).

Mr Gittins is attempting to lecture both sides of politics on what he thinks is the truth about fiscal policy. He writes:

It’s a sad state of affairs when good sense about the budget emanates from commentators on the sidelines rather than the Treasurer and shadow treasurer. Yet such is the case, because of the opposition’s consistently opportunistic approach to fiscal policy and the Labor government’s chronic failure to stand up to the nonsense its opponents have been peddling.

Mr Gittins counts himself as one of those “good sense” commentators, unfortunately.

The issue he is addressing is that the new Treasurer is still extolling the virtues of pursuing fiscal austerity and running budget surpluses when he:

… should be telling you, but aren’t: the more anxious we become about the economy losing speed before we make the transition to non-mining-led growth, the less urgent it becomes to get the budget back to surplus.

Which is definitely the message that the Government should be delivering to the Australian public given the state of the economy – slowing, with a cautious private sector producing spending growth that is incapable of supporting growth consistent with reductions in the very high rates of labour underutilisation that persist.

He correctly notes that Opposition spokesperson also gets this wrong and lies about the alleged dangers of public debt and deficits.

The problem is that Mr Gittins then chooses to add to this mis-information by contributing his own bit of mythology dressed up as some “unpacking” presumably by an expert (him) “for non-economists”.

Here it is:

Because budget balance … needs to be achieved only on average over a period of, say, a decade, it’s saying there’s nothing inevitably bad about deficits or inevitably good about surpluses.

So there’ll be times when deficits are appropriate and times when surpluses are. Which is which? Deficits are appropriate when the economy is growing well below its medium-term “trend” rate of about 3 per cent a year; surpluses are appropriate when the economy is growing near, at or above trend. Stick to that approach and, in the end, the deficits and surpluses will cancel each other out, leaving no lasting debt burden to be borne by our “children and grandchildren”.

Okay, question time: what is wrong with that reasoning? Answer: Lots.

First, a rate of growth of 3 per cent per annum will be insufficient to reduce labour underutilisation rates to their full employment levels. Once labour force growth resumed its trend rate (and participation rates rose to their levels before the downturn) and trend labour productivity growth rates are sustained – overall real GDP growth has to be closer to 4 per cent to eat into the huge pool of wasted labour.

That is, the trend before the crisis is not a full employment trend growth rate.

Second, the symmetry Mr Gittins appeals to is flawed. We cannot make any blanket statements about the appropriate cyclical behaviour of the budget balance until we know what is happening in the other sectors – private domestic and external.

What we know from an understanding of the national accounts framework is that the government surplus (deficit) will exactly equal ($-for-$) the non-government deficit (surplus).

Which means if the government is in balance over the cycle then the non-government sector will be in balance over the cycle.

However, once we decompose the non-government sector into its two constituent parts we can make a further conclusion. If the government sector is in balance over the cycle, then the private domestic sector deficit (surplus) will exactly equal ($-for-$) the external sector deficit (surplus).

That is, if there is an external deficit of say 3.75 per cent on average over the cycle then the private domestic sector will on average be in deficit – spending more than it is earning – over the same cycle – and accumulating increasing levels of debt.

Mr Gittins think this symmetry will come about “because of the operation of the budget’s built-in ‘automatic stabilisers’ which, when the economy is weak, cause tax collections to fall and welfare spending to grow and, when the economy is strong, go into reverse and cause tax collections to boom and welfare spending to fall”.

The impact of the automatic stabilisers on the budget balance do work in a counter-cyclical fashion – pushing the deficit up when private spending is weak and vice-versa.

Mr Gittins says:

So provided the government of the day doesn’t make changes of its own volition that work in the opposite direction to the stabilisers, they can be relied on to leave the budget balance just where it ought to be as the economy moves through the business cycle.

There is no guarantee that the rise and fall in the budget balance that comes about from the cyclical adjustments leave the budget balance in an appropriate position once we net out the cyclical aspects.

That is, what is left – the structural component of the budget balance (reflecting the discretionary spending and taxation choices of government) – may or may not be appropriate in relation to achieving full employment given the choices made by the private sector and the external sector.

Further, what happens if in the face of the fiscal drag coming from the government budget settings – as some non-government growth emerges – the non-government sector starts to fear rising unemployment etc and withdraws spending growth?

We know that when there is unemployment and falling income, private confidence will be low and subdued spending behaviour will follow. Firms will not invest until they are sure that they can sell the extra output that would be produced by the new productive infrastructure.

Consumers will not provide them with those guarantees because they are worried about their job viability.

Then add the fact that this is a balance sheet recession to the mix which requires years of private deleveraging to restore the sustainability of private balance sheets.

The result – a very drawn out period of subdued private spending overall.

Under those conditions, sustained budget deficits are required to support aggregate demand growth, which in turn, helps the private sector regain confidence.

But in a period of balance sheet adjustment, private spending will remain flat because the main task is reducing debt to sustainable levels.

However, there may be more to it than that. While it is clear the households are lifting their saving ratio out of disposable income and private investment remains relative subdued, my contention is that this is part of a long-term adjustment going on back to what we might consider to be normality.

I will come back to this.

I note Mr Gittins is very loose in his terminology here. Mainstream economists talk about balancing the budget over the economic (or business) cycle. He chooses to say a period “of, say, a decade”, which might be an entirely different temporal period to the underlying cycle. In fact, if we examine the economic cycles in Australia we will see a decade is not a very good approximation to any cyclical pattern.

Third, the public debt burden is never borne by “children and grandchildren”. The best thing a government can do to prevent entrenched disadvantage among our youth is to ensure they have work now. Enough work to go around at reasonable working conditions and sensible pay.

Work experience while on the dole is not a job. It is a cop out by the government and it will be in these ways that the government increases the burden on our future generations.

So when we are worrying about future burdens we should forget issues relating to public debt. It is clear we need an increased budget deficit now to provide enough jobs for all those 15-19 year olds who are unable to find work and who are beginning their days of disadvantage early. The long-term consequences of the unemployment are significant.

Please read my blog – The rising future burden on our kids – for more discussion on this point.

What about the new (old) normality conjecture?

The period before the neo-liberal era was characterised by several features.

1. Relatively continuous use of fiscal deficits.

2. Stable personal saving ratio of around 8-10 per cent of personal disposable income.

3. A consumption share of around 60-70 per cent of GDP.

4. Real wages growing in line with labour productivity – so that consumption could be driven by real wages growth rather than credit.

The neo-liberal period, which say those features reversed, is in fact the outlier – an atypical period. Which makes the claims by those who hold out that governments should return to surplus as a demonstration of fiscal responsibility rather difficult to understand.

Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point.

In many cases, where actual budget surpluses were recorded, the economies went into recession soon after. The important point though is that the surpluses were made possible by the unsustainable growth in private credit which drove private spending and boosted tax revenue.

It is highly likely that we are returning to a more normal environment now where the private sector are attempting to save more out of disposable income and reduce its reliance on credit.

Two implications arise if that if the private consumption is returning to more normal levels then two things follow:

1. The government will more likely have to run budget deficits of some magnitude indefinitely – as in the past.

2. Real wages growth will have to be more closely aligned with productivity growth to break the reliance on credit growth.

And when the nature of the balance sheet adjustments that are going on at present are included in the assessment these two points become amplified.

This makes the quest for fiscal austerity or following “balanced budget rules” appear mindless and very destructive. Where will growth ever come from if consumers are returning to higher saving ratios, firms are very cautious, all countries are eroding each other’s export markets, and governments are adding tot he malaise?

It is also clearly preferable, going on the logic outlined above, that households be supported by fiscal policy to return their balance sheets back into safe waters. That will require governments returning to their “normal” role – running budget deficits.

That is the “ongoing credit excess” in the private sector has to be reversed and that will require public net spending support.

Conclusion

The point is that unless we understand the central role that the currency-issuing body (government) plays in aggregate demand we will keep making policy positions that undermine or exacerbate the trends in the private economy.

Government should follow fiscal rules tied to the achievement and maintenance of full employment. Please read my blog – The full employment budget deficit condition – for more discussion on this point.

There is no doubt that the private behaviour is shifting back to what we might have considered to be more normal positions with respect to saving and consumption.

That will require governments returning to their historically normal behaviour – which means that fiscal austerity or consolidation or whatever you might like to call it – is the anathema of that requirement.

Mindless “balanced budget rules” fit into the latter category.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill employs just under 3,000 words to show that a more or less constant deficit is required. I can do it in 130 words. Here goes.

Given the 2% target inflation, the monetary base and national debt will decline in value in real terms at 2%pa. Assuming they are going to remain constant relative to GDP (which is a perfectly reasonable long term assumption) they’ll have to be topped up annually, and that can only be done via a deficit. So if the monetary base and national debt are say 50% of GDP, the deficit will need to be 0.5 times 0.02 equals 1% of GDP.

Moreover, if GDP expands at say 2%pa in real terms, then yet more deficit is needed: an extra 1% to be exact. Thus the total annual deficit required on the basis of the above hypothetical but quite reasonable figures is 2% of GDP (unless I’ve dropped a clanger).

There are various ways of looking at the need for an ongoing budget deficit (on average). And historical records reveal that budget deficits have been the norm, with surpluses the exception. There are fundamental reasons why deficits exist, and will always exist.

It also should be recognised that, under the current form of our financial system, any repayment of federal government debt will deprive the financial system of Treasury securities, which are held for reasons of liquidity management. Repaying central government debt is generally a bad idea.

“Repaying central government debt is generally a bad idea.”

Not much chance of that happening in Australia, John.

Treasury issues debt even when the budget’s in surplus, something else Ross Gittins doesn’t understand.

I am noticing a pattern. MMT macroeconomists describe extant system, develop theories and predictions based on this exposition and test them against against real data and real empirical events. MMT macroeconomists demonstrate that their theories explain the data and have predictive power. Mainstream (neoclassical) macroeconomists describe theoretical systems with little or no relation to the real world, develop ideology butressed by these unempirical theories and make predictions which all turn out to be egregiously off target. (Great Moderation??? Austerity led recovery???)

Net result of above events? MMT macroeconomists continue to be ignored. Mainstream (neoclassical) macroeconomists are lionised and followed slavishly by mainstream media, business and conventional academia. The real economy continues to get worse. People suffer. Nothing changes.

All this has to be evidence of a sclerotic, ossified and maladaptive system; a system which has become incapable of change even when change is vital; a dishonest system which cannot accept the truth or even imagine change; a system of entrenched sectional interests and archaic practices resisting change which would be for the greater common good. “System” here means the combined systems of ideas, systems of action based on those ideas and the real economy systems themselves. This lack of ability to change and adapt in the face of repeated failure is of crucial concern. Maladaptive entities (and systems) collapse in disorder, fail and go extinct.

Change or collapse, those are the choices.

If economics was a science Ikonoclast we’d be seeing some light by now.

I’m thinking of the famous Planck dictum about how science advances one funeral at a time.

That orthodox economics thrives suggests to me that it must be a religion.

Bill –

With the possible exception of export markets, the above are all cyclical factors. And the one that’s most sensitive to the economic cycles is the firms being very cautious.

A recovery in demand would make firms less cautious. Lower interest rates would make firms less cautious. And thier workers’ productivity rising faster than wages would make firms less cautious (and wouldn’t prevent real wage growth).

We don’t need balanced budgets over the economic cycle, but nor do we need continuous deficits. I had hoped by now you’d be investigating the circumstances where surpluses are desirable, but you still seem to have trouble accepting such circumstances even exist.

Ralph Musgrave –

You’re saying that a more or less constant deficit is required to keep national debt and monetary base constant. But MMT tells us those two things are largely irrelevant anyway.

iconoclast

it is not that illogical and poorly predicting economic orthodoxy represents systemic failure

it is a lobbying group for the rich

it’s success is to maintain control and wealth for the rich

recognition of the monetary power of the state and the ability to achieve full voluntary employment

would undermine the power of the wealthy

MMT could improve economic growth of our economic system but the wealthy and powerful

will fight till red in tooth and claw to protect what they have

Dear Aidan (at 2013/07/23 at 15:30)

You said:

The last statement is a blatant lie. In many posts here (and in my academic work) I have laid out the situation when a budget surplus is desirable. I have written many times (and dedicated whole blogs) to the case of Norway for example.

best wishes

bill

Dear Ralph Musgrave (at 2013/07/22 at 23:41)

Your 130 words would completely confuse a non-expert even on its own terms. To explain the economics of your 130 words would take considerably longer.

I try to educate by providing deeper explanation and historical context. Given the concepts are controversial anyway that means blogs have to be longer than 130 words.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Point taken. My 130 words were ULTRA ULTRA brief. But how about say 200 words, PLUS a fuller explanation? It’s a bit like explaining the theory of relativity: you give people the simple little formula E=MC2 plus a full explanation of why E=MC2. The whole BEAUTY of that theory is the way it boils down to a simple formula, and science awards top marks to simple ideas or formulas that explain a lot: that’s what makes people jump out of the baths shouting “eureka”.

Aidan,

I’ve no quarrel with the MMT claim that the size of national debt and monetary base are unimportant: i.e. governments shouldn’t worry about them. But that doesn’t mean those two have no effect (which is what I think you were rather implying – though I might have misunderstood you).

It’s a big like – I don’t know – the amount of oxygen absorbed by your lungs when you jog rather than walk. The amount absorbed does have effects, but it’s something that a normal healthy person can just forget about when switching from walk mode to jog mode.

Bill –

I stand corrected.

However, in situations without a large trade surplus, where the choice is between a public sector deficit and a private sector deficit, you do have a very strong bias to the former. Have you done any objective comparisons of more public spending v cutting interest rates in normal (non depression) economic circumstances?

Ikonoclast said: “This lack of ability to change and adapt in the face of repeated failure is of crucial concern.”

Insanity was defined by Albert Einstein as — doing the same thing again and again, each time expecting the result to be different.

Aidan, the whole GFC was a result of excessive private sector debt. It is inherently unstable and tends toward ponzi. So the idea that a currency issuing sovereign mitigates these types of excesses by promoting real wage growth as a basis for spending growth (as opposed to the credit channel we’ve become accustomed to) strikes me as a very sensible idea.

You’ve been around here a while. You know Bill’s attitude to monetary policy(interest rates) as a blunt policy tool.

Rgds

John Herman neoliberalism is not insane for the rich and powerful

accepting the unlimited spending power of the state

and full voluntary unemployment undermine that power

Kevin said: “neoliberalism is not insane for the rich and powerful”

I take the broader view that we are all on the same ship, and that if it strikes an iceberg (and in the absence of a timely means of rescue) then it seems likely that everyone will go down together, including the rich and powerful.