I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A case for public banking

I read an interesting research paper from staff at the New York Federal Reserve Bank (published March 2013) – How Much Do Bank Shocks Affect Investment? Evidence from Matched Bank-Firm Loan Data – which reported on an innovative study of the links between problems within individual banks and the investment performance of firms that deal with those banks in the context of highly concentrated banking sectors. While the study uses Japanese data, the findings are relevant for all nations, given that banking is typically highly concentrated across all advanced nations. The interesting conclusion that I draw from the study is that short of bank nationalisation, the findings provide support for the creation of public banks which utilise the currency monopoly enjoyed by government to provide a more stable environment for business firms during times of crisis in the private banking sector.

The motivation of the FRBNY Study is that as a result of “the high level of bank concentration in much of the OECD … large amounts of lending are channeled through a small number of institutions that are no longer small even in comparison to the largest economies”.

The conjecture to be examined is that “problems in a few large institutions could potentially have a large impact on aggregate lending and on real output”.

The study develops “direct estimates of borrower credit and lender supply shocks” using a “matched lender-borrower data set covering all loans received from all sources by every listed Japanese firm over the period 1990 to 2010”.

So they can identify bank loan supply “shocks directly from the data” rather than use indirect methods, which are common in other studies (and quite inaccurate).

The study therefore provides estimates of “how much financial institution shocks matter for overall firm-level and aggregate investment rates and establishes that creditor shocks are an important determinant of both”.

The interesting question they explore is whether “bank shocks matter for investment rates, and if so, how much?”. By investment, they are using the economists definition – augmenting productive capacity – rather than the more common usage, which includes purchase of financial assets (including bank deposits).

The research seeks to understand the way in which financial disturbances penetrate the real economy. In other words, how the Global Financial Crisis became the Great Recession (or Depression if we are talking about some of the Southern European economies).

The obvious link is that, given “firms borrow is to finance capital expenditures”, it seems clear that troubles in the banking sector would likely influence investment, which, in turn,

I will leave it your curiosity to learn about the details in the study. Essentially, they had access to “the values of total short and long-term lending from hundreds of financial institutions to thousands of listed firms: 272,302 loans in total”.

This allows them to detect the impact of credit shocks in particular banks on the “the overall investment rates of borrowers from these institutions” which is the first study of this kind.

The typical mainstream macroeconomic model ignores this question altogether. There is no sense that financial institutions are “large relative to the size of economies” that they operate in.

The bias in macroeconomics textbooks is towards a construction of the market in terms of “representative firms that are infinitesimal in size compared to any given market”. In other words, any “positive and negative idiosyncratic shocks to financial institutions cancel out due to the law of large numbers”.

This is one of the reasons that the mainstream macroeconomics theory failed to understand that the financial crisis, which manifest in 2007 and 2008 was brewing for some years. It is the reason that no mainstream textbook model could have predicted such a crisis – not necessarily the exact date or around the exact date but even the general tendency that was developing in the 1990s and beyond.

The reality in the banking sector is very different to the mainstream conception taught to students in typical macroeconomics and banking subjects.

As the authors of the FRBNY study show there is very high degrees of concentration in financial markets. They note that:

A striking regularity is that a few banks account for a substantial share of an economy’s loans.

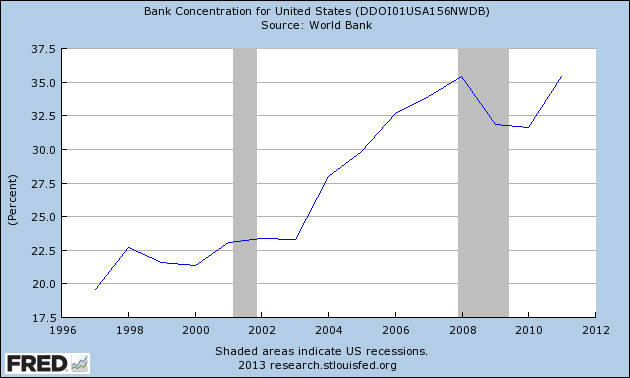

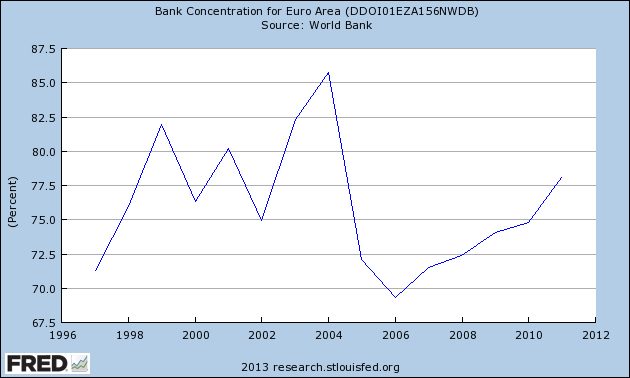

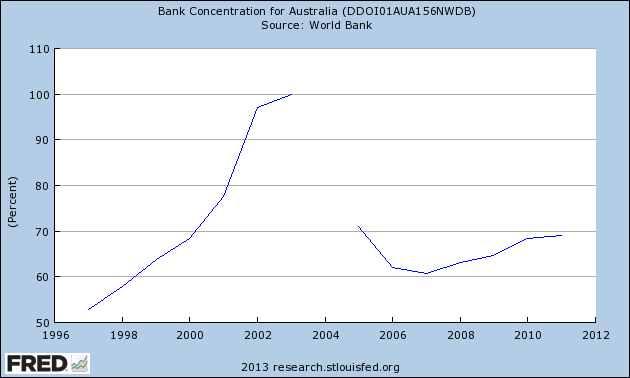

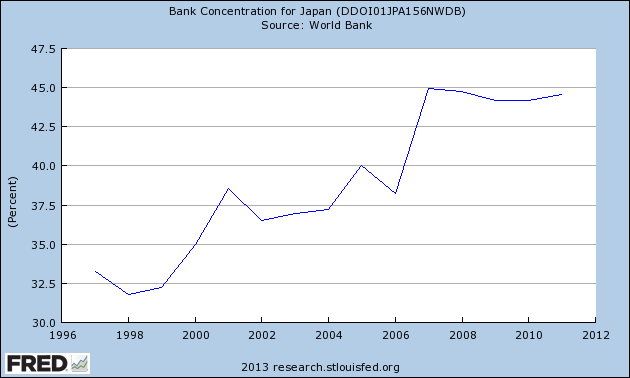

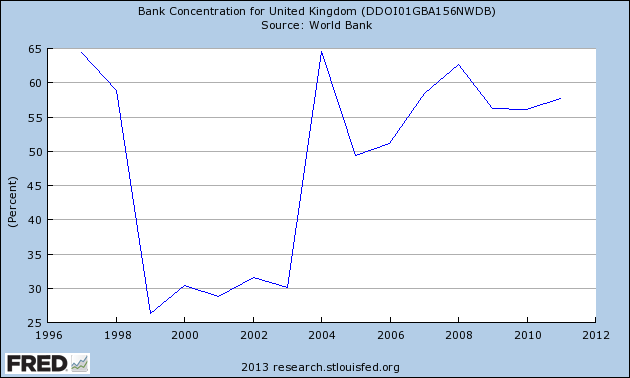

The following graphs (taken from the Fred2 database – but derived from World Bank data) show the concentration ratios in the banking sector for various nations. In 2011, for example, the combined assets of the three largest commercial banks as a share of total commercial banking assets was 78.1 per cent in the Euro area; 35.4 per cent in the US; 44.6 per cent in Japan; 68.9 per cent in Australia; 57.8 per cent for the UK.

The first graph shows the assets of three largest commercial banks in the US as a share of total commercial banking assets.

For the Eurozone:

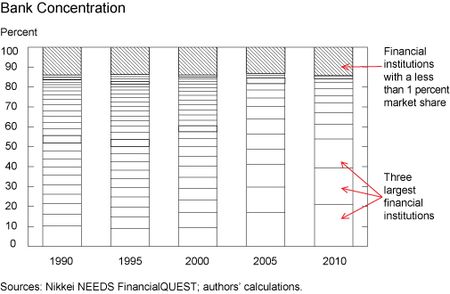

The FRBNY study produced the following graph (Figure 3, Page 16 – the annotations appeared in a shorter-article – Do Bank Shocks Affect Aggregate Investment? – published on July 8, 2013).

It shows for Japan, the evolution of bank concentration since 1990 by showing the percentage distribution of total lending. By 2010, the top three institutions accounted for 54 per cent of total lending.

This share (of the top 3) “increased dramatically, beginning in 2000”. Contrary to the neo-liberal claims that financial market deregulation was motivated by a desire to inject more concentration into markets, the reality is that many of the financial market reforms increased concentration ratios (that is, reduced competition).

The authors say for Japan that the “increase in concentration arose from changes in regulations that allowed the creation of holding companies, enabling a spate of financial institution mergers”.

Clearly, the concentration ratios differ across individual financial markets. I am delving deeper intot hat at present and will report back later. But what I have found to date is that the concentration ratios are lower in wholesale credit and capital markets areas but very high in the prime brokerage (providing services to hedge funds) market. More on this another day.

As an aside, this paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (2011) – Have Acquisitions of Failed Banks Increased the Concentration of U.S. Banking Markets? – examined whether the collapse of some 318 U.S. commercial banks and savings institutions between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010 (some 4 percent of the total number in operation on December 31, 2006) led to increased concentration in the US banking industry.

[Reference: Wheelock, D.C. (20011) ‘Have Acquisitions of Failed Banks Increased the Concentration of U.S. Banking Markets?’, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, May/June, 93(3), 155-68]

It found that “(t)he structure of the U.S. banking industry has changed dramatically since the mid-1980s, when the number of U.S. banks reached a post-World War II peak. Advances in information processing technology and the removal of most legal barriers to branch banking have been the main drivers of a substantial consolidation of the banking industry”.

On top of this trend to more concentration, the study found that of the 318 failures during 2007-10:

The assets and deposits of 171 of those failed banks were acquired by institutions that already had branches in markets served by the failed bank. Those acquisitions contributed to increased concentration of local banking markets. However … except for a few rural banking markets, acquisitions of failed banks by in-market competitors generally had only a small impact on market concentration. Most banks that failed during 2007-10 were small, and although many of those banks were acquired by much larger institutions, those acquisitions generally had little impact on market concentration. Acquisitions of larger banks that failed during 2007-10, such as the acquisition of Washington Mutual Bank by JPMorgan Chase Bank, also had only limited impact on the concentration in most of the banking markets involved.

You will appreciate that there is a long list of studies that have examined the question as to whether high concentration levels in the banking sector of a nation promotes greater risk of financial instability. There is no definitive answer to that question.

This relates, in part, to the “too big to fail” debate, which I will also address some time in the future as I do more research.

There are arguments pro and con reducing bank concentration. On the one hand, it is argued that high concentration ratios increase prices for financial products and generate what economists call supernormal profits – that is, gouge the consumers more than would be the case in a more competitive environment.

More concentrated banking sectors also tend to reduce the amount of lending to more risky segments of the market (for example, start-up companies and small business). Instead, they can gouge less risky markets and earn huge (safer) profits.

There is also an argument that collusion rises which reduces innovation and allows unsound practices to arise. Sweetheart deals with ratings agencies (although S&P have claimed in a current court case that they only offer “puffery” which should not be taken seriously – more on that another day) are encouraged in non-competitive environments.

On the other hand, some argue that more concentrated banking sectors are likely to be more financially stable. This is the opposite to the argument above about risk. They claim that because more concentrated banks do not have to take risks to generate profits the likelihood of major bank crashes is lessened.

However, these studies have often confused the cause and effect. By suggesting that nations with higher banking concentration coped better with the crisis they ignored the fact that these nations also had stricter regulative structures and, in some cases, the governments gave broad wholesale funding guarantees at the onset of the crisis. For example, as in Australia.

The FRBNY Study, however, does not examine this question. It concentrates on the seeing whether there is a direct link between some large bank encountering a negative shock to its capacity to lend and the investment behaviour of clients to that bank.

The point is that:

… if markets are dominated by a few financial institutions, cuts in lending due to some change in financial conditions in just a small number of banks have the potential to substantially affect aggregate lending. Moreover, if firms find it hard to find good substitutes for loans like issuing equity or debt, then it is possible for their investment rates to fall as well.

What did they find?

First, they show that the credit shocks experienced by firms is larger than the loan supply shocks of individual banks. So the “heterogeneity in firms’ credit shocks is quite large” relative to the bank shocks, which are, in turn, “quite substantial considering that only a few institutions account for half of all lending and therefore idiosyncratic shocks to a few institutions can move aggregate lending substantially”.

Second, “the variance of idiosyncratic bank shocks is particularly large in years when the financial system is under strain”, which means that the health of the banks becomes a significant issue “when a financial crisis pushes some, but not all, banks to the brink of bankruptcy”.

Third, “many of the investment opportunities faced by individual firms are not economy-wide but are specific to firms in a particular industry”. For example, “exchange rate movements that affect firms in export sectors differently from those in other sectors”. This still doesn’t negate the view that overall macroeconomic conditions – that is, the state of aggregate demand – matters. It does say, however, we need to always consider the composition of that demand as well as its level.

That finding suggest that fiscal policy will be a more effective tool than monetary policy because it can target specific components of aggregate demand and specific sectors of industry, whereas monetary policy is incapable of such fine-tuning.

Fourth, they find that the impact of bank shocks of investment is much higher when the firms rely on bank finance more heavily to fund such investment. That stands to reason.

But they also found that “negative bank shocks exert a positive impact on the investment of firms that are almost unreliant on loans for their financing needs, which may reflect the fact that firms that don’t rely much on loans for finance actually benefit relatively when credit conditions tighten”. In other words, capacity to expand market share is enhanced by firms that are unexposed to bank loan constraints.

What about the aggregate effects? Do the bank shocks work in a systematic fashion to undermine investment. In other words, this question addresses the mainstream bias towards offsetting effects coming from the law of large numbers noted above.

So the question is whether the finding that a specific bank shock leads to a credit shock for a specific firm translates into the aggregate – do bank shocks matter overall?

They conclude that bank loan supply shocks are very important in “understanding movements in aggregate lending and investment”.

After decomposing the different factors that can explain aggregate investment they conclude that “bank shocks … account for 40 percent of the fluctuations in aggregate investment”.

The implication they draw from their study is that:

… policymakers without detailed information on the major financial institutions are likely to have a difficult time understanding the causes of lending and investment fluctuations. A large portion of Japan’s aggregate economic fluctuations can be traced to the country’s banking problems.

So even if the large banks have lower failure rates (a finding identified in the study I cited above about the shifting concentration ratios in the US as a result of the crisis), shocks to specific large banks (for example, a loss of capital) “can cause investment declines by firms that would like to borrow”.

The obverse is also implied – “recapitalization of the right institutions can stimulate investment”.

The other implication, which attracted me to more detailed research in this area is that a key component of a stable growth strategy is to promote structures that allow for more certainty in investment behaviour.

The typical array of subsidies, tax breaks, etc, which I consider to be more in the vein of corporate welfare and often end up in the socialisation of losses, are in my view inferior strategies for a government to pursue.

There are many reforms to the banking sector that I would make – and I outline some of them in the following blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks.

But in the light of the research on concentration a more reliable way to reduce damaging variability in private investment is to deal with the problem of bank shocks in the first place in a highly concentrated sector.

In lieu of outright nationalisation, an effective governmental intervention would be to create a public bank, which would introduce competition into the banking sector and have the resources (courtesy of the currency monopoly) to provide constant bank loan alternatives to firms who deal with other large banks that encounter shocks to their capacity to lend.

Conclusion

I will write more about this in the future. At present it is a research topic that I am gathering more and more data about.

The point is obvious though. What happens in the financial sector – and trends that develop in that sector – provide major avenues for financial shocks to penetrate the real economy and undermine employment and output growth.

Government regulation and structural initiatives should understand the way in which these shocks transmit and reduce/eliminate the mechanisms.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

One thing you may want to consider in the research, if you’re not already, is whether it is prudent to reduce the overall level of bank lending and replace it with more injections of NFA from the government sector (either via tax cuts or more spending).

ie reduce the horizontal to vertical leverage ratio.

Seems like a political position that could sell – cut the bankers down to size and put more money in people’s pockets. Would it affect capital development too much though?

Neil,

Given that the ratio of bank assets to GDP in the UK is now ten times what it was prior to 30 years ago, a reduction in the size of the banking industry probably would do any harm. After all, what’s our bloated bank industry brought us other than trouble?

As to capital development, funding investment via a bank loan isn’t too clever as bank loans typically last only a couple of years. So I doubt capital development would be harmed.

Two articles that I have seen this week: “Goldman Sachs Profits Double on Strong Bond Trading” and “JP Morgan Profit Rises 31 % on Trading.” I didn’t read the details on either article but I take it that each company’s profit increase came from gambling instead of investments. I must be wrong since the media celebrated the releases.

Bill.

The private banks will not ever give up their ability to create money via extending loans and securitisation of junk assets. They have corrupted the political system and hence the ability to reform the monetary system.

Your theories are all sound , but you do not allow for the inherent corruption in the banking and political system.

We need leverage somehow, to alter this. That is the main issue we should address. We know the problem, we have solutions, but we are not allowed to implement these for the common good by the powerful lobbies of the wealthy and corrupt elites.

@Neil

What does this advertisement tell you ?

http://www.skoda.ie/finance/finance-examples

Finance is now super efficient.

The faster it can destroy core capital the more profits it can make.

Industry in Europe now orbits free banking and indeed this nexus is now complete with these free banking car /bank operations offering 0% finance for products in a glut while those who fall off the tighter and tighter monetary ridge are being prepped to be pushed on to the streets to make more space for “asset” creation.

Fiscal austerity is all about squeezing a surplus so that further free banking and the Industrial products which follow them back on top of a albeit smaller more absurd open economy of extreme long distance trade.

We need to redefine what exactly is capital creation ?

In my mind its more energy you can get out then what you put in….

Private cars & houses don’t qualify.

Canada has been doing something along the lines of Bill’s proposal for a long time, far as I can see.

See: http://www.positivemoney.org/2013/07/using-qe-to-rebuild-the-uk-economy-the-canadian-way/

I have just seen the latest UK unemployment figures, portrayed by the media and the employment minister as good news (unemployment fell by 57,000 over the quarter). Not one of them mentioned that only 16,000 jobs were created, and the rest of the drop was caused by some 40,000 people leaving the labour market.

I’d call that a very bad omen.

Daniel, the public banking institute has been promoting this idea at the regional level for years now: http://www.publicbankinginstitute.org

I think they’ve given up on any reasonable chance of public banking at the federal level, at least anytime soon. North Dakota already has their own bank, and other states are at least talking about it. (And some people believe it’s not entirely a coincidence that North Dakota also has the lowest unemployment in the US, 3.2% as of May 2013.)

I like the idea of starting small with public banking–if successful, it allows the idea to get a foothold and prove itself. State-owned banks don’t have the same resources they would at the federal level, however by depositing tax revenues into a state bank they can be used to develop the state economy rather than the dubious investments in a Wall St. bank.

There are two aspects to the problem you have identified Daniel. In addition to corruption of the political system, there is corruption of the economics profession. If economists had thought and behaved differently during the past few decades, then the global financial crises we have been witnessing would never have occurred. It also should be recognised that an orthodox training in economics is a cretinising process. The more thoughtful students of economics recognise its deficiencies, and its pretensions to being a science. Unfortunately most economists have no training in scientific philosophy or methodology, and therefore do not appreciate that the mere use of sophisticated mathematics does not in any way confer scientific status upon an academic discipline. Mathematics is a very useful tool however it has always been true that garbage in equals garbage out.

Ireland has now become a extreme police / coercion anti state.

The taxing authority ( it was never a government) has taken another step along this dark road.

Using the power of fiat / law to bail out credit banks and their hopeless “assets” on people who don’t even use state propaganda services.

http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/every-single-home-to-be-hit-with-new-broadcasting-charge-29428338.html

MMT Intellectual debates about the validity of public banking vs private banking is worthless as both the public and private monetary spheres is one under the western model of banking control.

John Hermann,

I think it’s clear that there is some sort of adverse selection process going on with orthodox economics. Only those who are able to unquestionably believe all that BS become new teachers/thinkers.

Public banking is working well in China. Seems like enterpreneurs are the people who need socialism most – state arranged loans for capital development.

Would it affect capital development too much though?

Neil, Mariana Mazzucato’s new book The Entrepreneurial State outlines the way in which capital development in the developed world has depended on massive state subsidization and investment. Shifting the provision of NFA’s away from the central bank and credit markets toward direct public spending via treasury departments should focus, in my opinion, not just on transfers to consumers to drive uncoordinated consumer demand, but on directed public investment goals and larger projects.

Jeff — the Public Banking Institute is certainly not giving up on the idea of a national bank. The possibility for providing banking services through the US Postal Service is quite high, with the credit used to fund a National Infrastructure Bank. I’m working in D.C. on this exact project. More here: http://www.nalc.org/news/precord/PresMesPDF/07-2013_president.pdf

— Marc