I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Balancing budget over the cycle is not a sound fiscal rule

There were three data releases from the Australian Bureau of Statistics today and all showed that the Australian economy is continuing to weaken. The – Business Indicators, Australia – showed that company gross operating profits fell for the fifth consecutive quarter (7 our of the last 10). Second, the data for – Building Approvals, Australia – which is one indicator of the strength of the housing market and the construction industry, showed that the seasonally adjusted estimate for total dwelling approved fell by 2.4 per cent in January, the second consecutive monthly fall. Finally, the – Mineral and Petroleum Exploration, Australia – showed that “mineral exploration expenditure decreased by 10.2% in the December quarter 2012”. What this data tells us is that private spending is weak and probably weakening. It tells us that fiscal policy should be expansionary rather than following its present course of austerity. It tells us that unless the government reverses its current strategy, the Australian economy will weaken further. It also tells us that commentators and politicians that think fiscal rules such as “balancing the budget over the cycle” are sound strategies to adopt are either operating in a cloud of ignorance or deliberately misleading the public as to the likely outcomes that would follow from pursuing such a rule.

Last week, the ABS released their latest – Private New Capital Expenditure and Expected Expenditure, Australia – for the December quarter, which will feed into the National Accounts for December that will be released this Wednesday. This data also confirmed that things are not as rosy as some would think.

The fall in building approvals has confounded those who believe that monetary policy is an effective counter-stabilising policy tool. The Reserve Bank of Australia has now cut interest rates x times since 2011, as they try to defend the failing economy in the face of on-going fiscal austerity and declining private expenditure growth.

On November 2, 2011 the RBA target rate was cut from 4.75 per cent to 4.5 per cent. Since then it has been cut 6 times to its present level of 3 per cent.

The RBA cash rate is now at its lowest level since it was at 3 per cent during the worrying months of May 2009 to September 2009, when the economy was poised on the knife edge of contraction or expansion as the fiscal stimulus was working its way through to aggregate demand.

The fact that the economy is not rebounding in the wake of all this monetary “easing” indicates that monetary policy is an ineffective aggregate policy tool for counter-stabilisation (influencing aggregate demand in a responsive way).

In relation to the capital expenditure data release, Fairfax columnist Michael Pascoe wrote (March 1, 2013) – Capital goes on strike. The article said that:

I don’t know what happy drug the markets were on yesterday but it must have been powerful to get a positive reaction out of poor private fixed capital investment figures. For mine, the capex numbers do nothing to make a March interest rate cut less likely as capital is close to going on strike outside the resources sector.

Michael Pascoe emphasises that this dataset not only provides us with “backward-looking” data about capital expenditure, but also projects what firms plan to do in the period ahead, which is a valuable guide to where GDP growth is likely to be over the next 12 or so months.

This conclusion points to the fact that, while mining investment remains strong but will weaken in the coming year as commodity prices fall of their latest peak, investment in the manufacturing sector is expected to fall “by 16 per cent next financial year after slicing it by 29 per cent this year”.

Further, the “already weak construction sector” is “expecting to more than halve this year’s capex – down from $4.2 billion to just $1.9 billion”.

The mining sector data shows that the “construction phase of the resources boom has made to our economic growth is tailing off”. So mining companies will still enjoy strong revenue growth as they sell the ore but the construction industry will contract as the demand for new infrastructure declines sharply.

What this tells us about the coming year is that unless there is dramatic boost in housing construction (and the latest data is pointing away from that conclusion) then the economy is likely to slow even further.

That is because private consumption is steady as households maintain their determination to keep the household saving ratio at around 10 per cent (which is a return to their old behaviour before the credit binge) and business investment will contract.

Dragging all that moderation down even further is the obsession that the federal government has with fiscal austerity in its mad and irresponsible quest to balance the budget over the cycle. Any government that pursued that fiscal rule in the current climate would be further undermining growth and denying the private domestic sector the income support, which will be essential for it to reduce its massive debt burden (following the credit binge).

The reason I am concentrating on all this data today was to stay calm after reading a column from the Sydney Morning Herald economics editor (Ross Gittins) (March 4, 2013) – Hockey would be no soft touch as treasurer – which sought to extol the fiscal rectitude and wisdom of the Opposition Treasury spokesperson (one Joe Hockey), who will be the Federal Treasurer when the abysmal Labor Government is kicked out by the electorate at the upcoming Federal election in September.

As an aside, our politicians do not seem to be very wired to the opinions of the voters. The Labor Party are heading to another electoral massacre – they were slaughtered in the state elections in Victoria, Queensland, and New South Wales, then the Northern Territory over the last few years – and they still don’t get it. Their leadership and policy framework is deeply flawed and they seem oblivious to that.

Things have got so bad that the UN Monitor – has been called in by the Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) and have (Source):

… expressed concerns to the federal government over welfare payment cuts to single parents. The UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights is reported to have written to the government following the decision to move about 84,000 parents to the unemployment Newstart allowance when their youngest child turns eight. More than 60,000 single parents now receive between $60 to $100 a week less under the change … The UN monitor is reported to have been waiting for a reply from the government for more than four months. Prime Minister Julia Gillard rejected the UN concerns

Such is our so-called “progressive” Labor government. The only problem is that with the conservative opposition, things will get worse. A rock and a hard place applies here as well as in all the advanced nations as a result of the dominance of neo-liberalism across the political spectrum. Until that dominance is ended the progressive cause is lost.

Anyway back to to article about the probable future Treasurer. I am focusing on it because it highlights a basic problem that even the progressives have with macroeconomics. Ross Gittins is no conservative and steers towards the more social conscious side of the debate. But he consistently provides his readers with misleading information at the macroeconomic level.

Given the importance of macroeconomic constraints on individual behaviour, many fundamental errors of reasoning are made if we ignore those constraints.

Take this appraisal of the probable future Treasurer and those allegedly giving him advice:

Hockey is much underestimated. If you’ve been watching you’ve seen him progressively donning the onerous responsibilities of the treasurership, the greatest of which is making it all add up … As a former cabinet minister, Hockey knows it’s hard for governments to get away with such wishful thinking. If you’ve been listening carefully you’ll have noticed Hockey quietly taking an economic rationalist approach while others demonstrated their lack of economic nous. Those who doubt the strength of Tony Abbott’s economics team should note that Hockey would be backed by Senator Arthur Sinodinos, a former senior Treasury officer. I believe Sinodinos played a key part in formulating the “medium-term fiscal strategy” – “to maintain budget balance, on average, over the course of the economic cycle” – which the Libs developed when last in opposition.

If so, Sinodinos deserves induction to the fiscal hall of fame. There have been few more important or wiser contributions to good macro-management of our economy.

“Few more important or wiser contributions to good macro-management of our economy” … which tells you Ross Gittins, either doesn’t know what the implications of that fiscal rule are or is choosing to mislead his readership.

To explore what this means, we can invoke the sectoral balances framework, which summarises, in a succinct accounting relationship, the basic interactions between the broad sectoral flows in the economy. At the most aggregate, it captures the relationship between the government and non-government sectors. It is sometimes useful to decompose the non-government sector into the private domestic sector and the external sector.

In turn, the private domestic sector is typically disaggregated in macroeconomics textbooks into the household and firm sub-sectors. From behavioural perspective, households consume and save (these are flows) while business firms produce and invest (also flows).

A flow is measured the unit of time, whereas a stock is measured at a point in time. We don’t talk about the “stock” of water flowing from a tap. We express the flow in terms of so many litres per minute or whatever. This water flow can fill up a swimming pool and we would say that at the current time, the pool has X thousand litres of water in it.

Using the three sector model (government, private domestic and external), we consider the spending flows derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

where GDP is total national output and income, C is final consumption spending, I is private investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

The spending flows perspective (in Equation (1)) highlights the sources of aggregate expenditure or demand, which drives total output and national income determination.

We can take another perspective of the national income accounts, by focusing on how the final GDP or income (Y) that is generated by the spending flows is used by households. GDP (national income) ultimately comes back to households who consume it (C), save it (S) or pay taxes with it to government (T), once all the distributions are made.

So:

(2) GDP = C + S + T

where S is total household saving and T is total taxation.

This says that households pay taxation to the government, which then leaves them with disposable income (GDP – T). Households then choose to consume a proportion of their disposable income. The disposable income that remains after the flow of consumption spending is what macroeconomists call saving.

So the basic national accounts that provide income and expenditure data can be conceptualised in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of aggregate expenditure; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the national income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances for the external sector, the government sector and the private domestic sector.

Remember the national accounts is built on the fact (an accounting identity) that total expenditure equals total output equals total national income.

We can bring the two perspectives (sources and uses) of GDP together (because they are both just “views” of total output or national income) to write:

(3) C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(3a) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

We can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations by re-arranging Equation (3a):

(4) (S – I) + (T – G) – (X – M) = 0

or:

(4a) (S – I) = (X – M) – (T – G)

The sectoral balances equation (4a) says that Total household savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal net exports (X – M) minus the budget surplus (T – G). The external surplus (X – M) represents the net saving of non-residents. So if (X – M) < 0, that is, in deficit, the local economy is using the net saving of foreigners. Equation (4a) tells us that for an external balance of zero (X - M) = 0, the private domestic surplus will be exactly equal to the budget deficit or another way of saying this (which follows more closely the way I have expressed the balances here) is that the private domestic deficit increases as the government surplus increases. All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and are not matters of opinion. As a result of all the balances being sensitive to national income movements (for example, saving, taxes and imports rises with national income), the economy ensures this accounting relationship is maintained through GDP movements. That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (S – I) is positive if in surplus (private domestic sector is spending less overall than its income) and negative if in deficit (private domestic sector is spending more overall than its income).

- The Budget Surplus (T – G) is positive if in surplus (government spending less than it is taking out of the economy via taxation) and negative if in deficit (government spending more than it is taking out of the economy via taxation).

- The External (Current Account) balance (X – M) is positive if in surplus (external sector adding more to aggregate demand via exports than is being drained by imports and net income transfers) and negative if in deficit (external sector draining aggregate demand because export income is lower than the sum of import spending and net income flows).

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

Note that if the private domestic sector is in deficit we are not suggesting that the households are not saving. It just means that overall, once all the individual spending and saving decisions that make up that sector are aggregated, the sector is spending more than its income – that is, dissaving.

To explain this more, note that the (S – I) relates to the overall balance of the private domestic sector (not the household sector). It is clear that if we had a balanced budget (G = T) and an external balance (X = M) then (S – I) = 0.

But this would not mean that there was a zero flow of saving in the economy. Households could still be consuming less than their disposable income which means that S > 0.

What it means is that the private domestic sector overall is not saving because it is spending as much as it earns.

It also means that when the government is running a balanced budget the non-government sector must be spending exactly what it earns and is not accumulating net financial assets (as a sector). When the external sector is in balance, then that conclusion applies directly to the private domestic sector.

Think about this carefully. Clearly, if households do not consume all their disposable income each period then they are generating a flow of saving. This is quite a different concept to the notion of the private domestic sector (which is the sum of households and firms) saving overall. The latter concept (saving overall) refers to whether the private domestic sector is spending more than it is earning, rather than just the household sector as part of that aggregate.

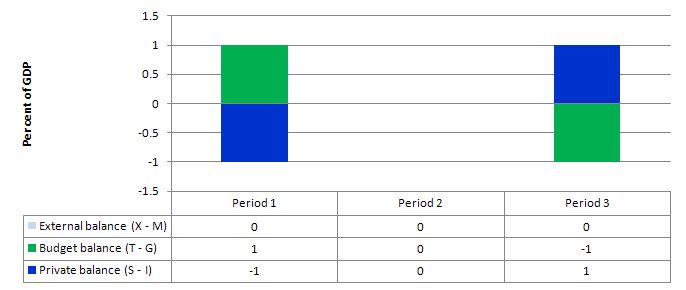

Consider the following graph which shows three situations where the external sector is in balance.

Period 1, the budget is in surplus (T – G = 1) and the private balance is in deficit (S – I = -1). This means that the private domestic sector is spending more (via consumption and investment taken together) than it is earning. So it is dissaving overall. Note that households could still be saving (that is, not spending all of their disposable income). But as a sector, the combination of firms and households would be dissaving.

With the external balance equal to 0, the general rule that the government surplus (deficit) equals the non-government deficit (surplus) applies to the government and the private domestic sector.

In Period 3, the budget is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save overall (S – I = 1).

Period 2, is the case in point and the sectoral balances show that if the external sector is in balance and the government is able to achieve a fiscal balance, then the private domestic sector must also be in balance. This means that the private domestic sector is spending exactly what they earn and so overall are not saving. However, the household sector could still be generating flows of saving (consumption less than disposable income) and this overall condition still hold.

The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise. The problem is that if the private domestic sector desires to save overall then this outcome will be unstable and would lead to changes in the other balances as national income changed in response to the decline in private spending.

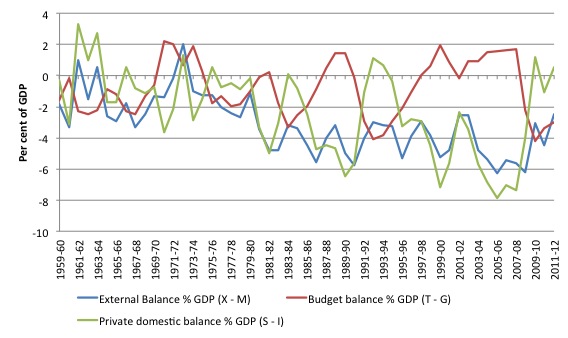

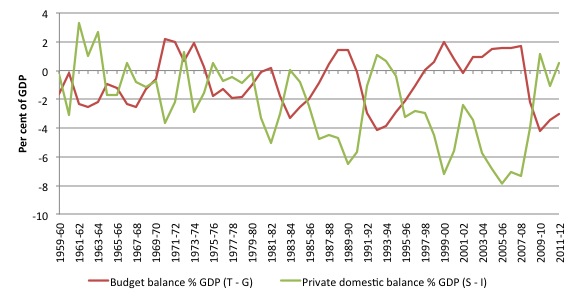

The following graphs show the sectoral balances for Australia from the fiscal year 1959-60 to 2011-12. The first shows all three balances, while the second deletes the external balance (X-M) to show the relationship between the government budget balance (T-G) and the private domestic balance (S-I).

The data is taken from the ABS (Balance of Payments and National Accounts).

It is clear that since the early 1970s, the external balance has been in deficit. Since 1959-60 to 2011-12, the average current account deficit has been 3.1 per cent of GDP. Since the 1980s, the external balance has fluctuated around 4 per cent of GDP.

Given that “constancy” in the external situation, data also shows the close inverse relationship between the budget deficit and the private domestic surplus. The period 1996-2007 is worth noting. The Federal government ran increasing surpluses over most of this period as the private domestic sector went into increasing deficit overall.

The latter, driven by credit growth provided the expenditure flow to drive growth sufficiently that the government could run surpluses (growth in tax revenue was strong). But it was an unsustainable growth strategy because the stock manifestation of the cumulative private domestic deficits was the record levels of indebtedness that were accumulated.

It is clear that the private domestic sector (particularly households) are now returning to the pre-credit binge behaviour as they try to reduce the precariousness of their balance sheets. That behaviour, given the external sector constancy, was associated with continuous budget deficits.

If the private domestic sector had not been lured by the financial engineers in the late 1990s into the 2000s to binge on credit, the Government could not have run the surpluses. Its attempts at fiscal austerity would have come unstuck because national income growth would have collapsed under the weight of external deficits draining demand, private sector frugality and fiscal drag.

This graph just highlights the close relationship between the budget balance and the private domestic balance.

The following analysis provides further insights into the soundness of the “balanced budget over the cycle” fiscal rule.

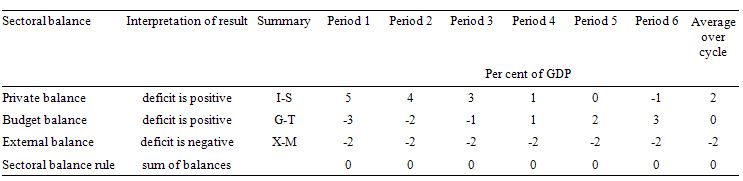

The following Table shows a stylised business cycle (running over 6 periods) with some simplifications but includes the real world fact that Australia tends to run a current account deficit as a matter of course.

The economy shown in this Table is running a surplus in the first three periods. The surpluses are declining and then in periods 4 to 6, the government runs increasing deficits.

Over the entire cycle, the balanced budget rule would be achieved as the budget balances average to zero (see last column). So the deficits are covered by fully offsetting surpluses over the cycle.

The simplification is the constant external deficit (that is, no cyclical sensitivity) of 2 per cent of GDP over the entire cycle. In actual fact, there is likely to be some cyclical variation in the external balance. But the assumption of constancy here does not violate real world experience sufficiently to alter the conclusion we make below. It just means we can see what the private domestic balance is doing more clearly.

When the budget balance is in surplus, the private balance is in deficit. The larger the budget surplus the larger the private deficit for a given external deficit.

As the budget moves into deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance and then finally in Period 6, the budget deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) and so the private domestic sector can save overall. The budget deficits are underpinning spending and allowing income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector.

On average over the cycle, under these conditions (balanced public budget) the private domestic deficit exactly equals the external deficit. As a result, the private domestic sector will always be spending more than they earn (becoming increasingly indebted) if such a fiscal rule was enforced for external deficit nations.

The private domestic sector overall can only save in these circumstances if the government runs a deficit.

Clearly, under these conditions, if the balanced budget rule was enforced the private debt problem would escalate and, ultimately be unsustainable. That would lead to a contraction in private spending and a recession would follow.

It is normal for the federal government to run continuous deficits (small relative to GDP). These deficits support private sector saving overall (and keeps private debt manageable) in the fact of more or less constant external deficits.

Job Guarantee

Just a note to recognise that the European Commission has now agreed to introduce a – Youth Guarantee.

The agreement means that:

… young people up to age 25 receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of leaving school or becoming unemployed.

I will consider this scheme in detail once more information is forthcoming but on the face of it is an excellent initiative.

Conclusion

While the balanced budget rule over the cycle seems reasonable – the government runs surpluses in good times and deficits in bad times – it in fact will lead to unsustainable outcomes depending on the behaviour of the external sector.

That fiscal rule would ensure that over each cycle, the private domestic sector balance mirrored the external sector balance. That means, if the external sector is in deficit more or less always (and over the cycle), the private domestic sector will also be in deficit and becoming increasingly indebted.

Ultimately that is not a sustainable growth strategy and is not a responsible macroeconomic policy stance to adopt.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, your conclusioon is wrong for two reasons, and silly for a third reason:

Firstly it is not true that increasing private sector debt is unsustainable. As long as productivity is rising and/or interest rates are falling, there is no good reason why it can’t be sustainable as a trend, even though cyclical factors will almost certainly prevent it from being continuously sustainable.

Secondly your assumption that the external balance would stay negative is dodgy. With a balanced government budget over the cycle, interest rates would low, therefore the private sector’s net foreign debt is likely to fall.

But most importantly it fails to consider what alternatives are available. MMT tells us that there are various alternatives that might be better than balancing the budget, but so far you’ve not told us how to compare them quantatively. And that matters s lot. MMT hss the potential to revolutionize the cost benefit analysis process, but it can’t do so until someone figures out exactly how.

The basic reason why it makes no sense to try to balance the budget over the cycle can be stated in about one about one fiftieth the number of words used by Bill above. The reason is thus.

Assuming inflation of about 2%, the national debt and monetary base will shrink in real terms by about 2%pa. If the national debt and monetary base are to be maintained at a constant ratio relative to GDP, it follows that they must be regularly topped up, and that can only be done via a deficit.

Obviously the assumption that the national debt stays constant relative to GDP can look a bit silly if you take just one decade or two (e.g. in the UK it declined from about 200% of GDP just after WWII to a quarter than amount 20 years later). But if you take the VERY LONG TERM – a century – the national debt to GDP ratio does not vary much.

Secondly, if the economy is growing at say 2% a year in real terms, and still assuming the above ratios are to remain constant, than that requires even more deficit.

Re Aiden’s comment above, I’m baffled by it.

@Aidan

“With a balanced government budget over the cycle, interest rates would low”

Are you sure you’ve got a good understanding of MMT?

Ralph, if you tell me why my comments baffle you, I can explain it further. If it’s and that matters s lot, that was a typo – it was meant to be and that matters a lot.

And if the national debt to GDP ratio is little different to what it was a century ago, that’s coincidence. It varies enormously as the result of policy decisions, and there’s no long term stabilizing factor.

“With a balanced government budget over the cycle, interest rates would low, therefore the private sector’s net foreign debt is likely to fall.”

Balanced budgets reduce the quantity of reserves and thereby drive short-term interests rates up from zero.

Ben, the quantity of resereves is only a very minor contributor to the interest rate. The major contributor is the rate the central bank sets (which is not zero except when there’s a gross failure of fiscal policy).

With a balanced government budget over the cycle, interest rates would need to be lower to encourage the private sector to invest more. With a government deficit, interest rates would need to be higher for the same inflationary outcome.

Dear Aidan

Your claims that private deficits can be maintained indefinitely fly in the face of reality. Think about the arithmetic for a moment. A continuous external deficit of 4 per cent of GDP and a balanced budget would require a massive private sector deficit to be ongoing for growth to be maintained. Historically, the household sector has saved about 10 per cent of disposable income. That means the growth in private capital formation has to not only cover the household saving but then the external deficit as well, and be on-going.

Further, given Australia imports capital equipment, it is likely the external deficit would rise under those circumstances therefore requiring even more private sector investment.

There has never been a time in history when all those events have coincided. Investment has never found that much indefinite productivity growth to maintain rates of return consistent with such a trend.

Your carping exposes a lack of understanding of these aggregates in history and reality.

Sorry.

Best wishes

bill

Bill,

You point out that the Howard government was able to run surpluses due to the tax receipts from the additional aggregate spending from new private debt creation, so it could be that balancing the budget may be perfectly reasonable over a particular period if private debt is taken into account.

Is there a more extensive set of the sectoral balance equations which also cover private debt accumulation with the associated increase in consumption and tax receipts, and then the subsequent drag as this debt has to eventually be paid off?

Cheers.

Dear Bill

Historically households have been very debt averse, land has been cheap, and interest rates have been high. Those things are no longer the case, so I don’t think the historical rate is of much relevance. But even if it does somehow return to that level, I don’t regard it as an insurmountable impediment.

I fully accept your point about the growth in private capital formation. But the result of it is increasingly export oriented, so importing more capital equipment won’t necessarily result in a rising external deficit – or indeed any external deficit.

I don’t care if the current situation is different from anything in the past. There’s a first time for everything, and what counts is advantage, not precedent.

Ultimately we don’t know the length of the cycle so we won’t be able to tell where the budget’s going until we get there. So a sensible course of action is to not worry about it too much, but aim for a balanced budget over the cycle unless there is a good reason not to. And long term unsustainability is not a good reason not to in the short term, because policies can be changed if and when needed.

What is a good reason not to aim for a balanced budget over the cycle is if there are better things to do with the money than cutting interest rates. Infrastructure is usually a good example as it has as long term deflationary effect – but how do you compare the effects of better infrastructure with those of lower interest rates or lower taxes? Answering that question (without recourse to claims of unsustainability of increasing private debt) would make MMT far more useful.

“(4a) (S – I) = (X – M) – (T – G)”

We can recognize the government identity G = T + PB where PB is Printed/Borrowed money needed to bring the government budget into balance. Of course, PB will be negative if government is running a surplus which seldom happens in the United States. We can rearrange and substitute to find

I + (X-M) = S – PB.

This presentation of the formula makes it easy to see that government deficits decrease investment by subtracting from savings.

I think this highlights the tension between consumption of real labor and goods contrasted with the flow of paper money. More money increases savings, but more money also means more goods and labor consumed, usually not for investment purposes.

Aidan

“With a balanced government budget over the cycle, interest rates would need to be lower to encourage the private sector to invest more.”

Though a lower Target Rate can make private investment more affordable, you seem to assume that investment opportunities actually exist – this being the main limiting factor where the target rate is low.

Government can only encourage these investment opportunities to exist by ensuring that there is adequate spending and growth in the economy, and that means running a large enough budget deficit.

Bill,

I fear the EU Youth Guarantee is an attempt to massage the unemployment figures for a while from current horrendous levels and then quietly dropped (UK experience springs to mind).

Still perhaps Portugal et al will take them at face value and spend the EU grants and reverse the austerity downward spiral – we can live in hope!

Dear Roger (2013/03/05 at 1:01)

There is a danger in trying to use the sectoral balances to advance a static theory – that is the trap you have fallen into. The balances are ex post accounting outcomes derived from national income shifts that are driven by changes in the individual spending and leakage components.

So a budget deficit doesn’t subtract from national saving (where national saving is private households spending less than their disposable income) – it adds to it by increasing income. So from a behavioural sense – a priori as PB rises, so does S, so does M and probably I, given that firms invest to ensure they can meet future demands on productive capacity.

best wishes

bill

“Ben, the quantity of resereves is only a very minor contributor to the interest rate. The major contributor is the rate the central bank sets.”

Incorrect. The quantity of reserves is neutralized IF the central bank pays interest on reserves. If it does not the central bank must sell bonds to drain excess reserves, otherwise it loses control of the overnight rate.

Furthermore your quote above refutes your initial assertion: first you argue rates are kept low by balanced budgets, now you claim rates are whatever the central bank wants them to be. You can’t have it both ways.

CharlesJ, what you describe is the current situation, and I am not saying the governmen budget shouuld currently be balanced. But over most of the cycle the investment opportunities do exist and over much of the cycle it is sensible for the government to run surpluses.

Ben, I am assuming the central bank pays interest on reserves and/or sells bonds. Indeed that’s part of the reason why they’re only a minor contributor to commercial interest rates.

My initial assumption is not refuted and there is no logical contradiction. Although the central bank sets interest rates, they don’t do so on a whim; rather they set them to achieve some economic objective (usually inflation control, but my argument is still valid if the target were growth or employment related). Lower rates are expansionary; higher rates contractionary. The more contractionary fiscal policy (taxation and government spending) is over the cycle, the more expansionary monetary policy (interest rates) has to be to meet the objective target. Likewise the more expansionary fiscal policy is, the more contractionary monetary policy has to be to meet that target.

A balanced budget over the economic cycle is more contractionary than a deficit, hence it would result in lower interest rates. It’s almost that simple!

The almost is there because the things governments spend their money on often have a deflationary effect. I’m waiting for Bill to tell us how this can be calculated, but he doesn’t seem to know.

I think that budget surplus or even balanced budget is a sign of a sick economy. It is a sign that private sector is in the mids of a unsustainable asset price bubble and credit binge. Lots of people are going to be hurt when bubble finally collapses.

“Lower rates are expansionary; higher rates contractionary.”

This is the problem. The available evidence does not support your conclusion that one state is expansionary and one is contractionary. To the contrary, it is quite possible that low interest rates can exert a contractionary effect on an economy by reducing incomes to the private sector, just as high rates can trigger increased spending by inflation those incomes. Monetary policy is extraordinarily crude for economic management.

“Ben, I am assuming the central bank pays interest on reserves and/or sells bonds. Indeed that’s part of the reason why they’re only a minor contributor to commercial interest rates.”

Once again this contradicts previous statements. The central bank does not manage the overnight rate by declaration. It must control the quantity of reserves to control the rate. Given you’ve just acknowledged this it seems very odd that you then immediately follow by arguing reserve quantities are only a “minor contributor”.

Ben, there is overwhelming evidence to show that lower interest rates are expansionary and higher interest rates are contractionary. There may be a small effect the other way round from a few extremely debt averse individuals, but that is insignificant because it’s swamped by the effect of businesses and individuals being able to afford to borrow more when interest rates are lower.

As for the quantity of reserves, Bill has proven that (contrary to the claims of many mainstream economists) it’s of little significance. There does need to be some mechanism for draining excess reserves, and paying the overnight rate serves that purpose, but declaration is a perfectly adequate way of setting the overnight rate.

In the end, the issue about whether the private sector can continue to accumulate debt is not that relevant. What are most relevant are the net savings and spending desires of the private sector. Assuming NX = 0 and the private sector wishes to positively net save out of current income (i.e., S > I), it can only do so if the central govt operates a budget deficit (G > T). If the central govt wants to operate a budget surplus, the private sector has to make a decision – does it maintain its spending desires and abandon its net savings desires, or does it abandon its spending desires to satisfy its net savings desires? It cannot maintain both its spending and net savings desires.

Should it choose to maintain its spending desires and abandon its net savings desires (aka 1992-2007), GDP remains bouyant (u/e remains low) and the central govt achieves its budget surplus. But the private sector must negatively net save. The likes of Peter Costello (the Australian Federal Treaurer at the time) give themselves a pat on the back and boneheads proclaim they are brilliant managers of the economy. What they don’t realise is that they are setting the economy up to crash.

At some point, the private sector decides it no longer wants to maintain its spending desires, but to start positively net saving (2007). It must then abandon its spending desires. Private sector spending collapses and the economy goes into recession if the spending gap is not filled by the central govt. Since the private sector has had an historical tendency to positively net save, and assuming this trend continues, only central govt deficits can prevent periodical collapses of the economy. Hence central govt deficits should be the norm.

Some will say that budget deficits can be avoided if a nation net exports (X > M). True, but: (1) it requires other nations to net import (and central govts of other nations to run budget deficits); (2) a nation can’t just net export at will; and (3) net exporting is stupid! Net exporting involves giving up more useful stuff to foreigners than you receive in return, which is non-sensical strategy when you have a central govt, through deficit spending, that can provide the net financial assets to meet the private sector’s net savings desires and can give the useful stuff (the difference between X and M) back to its citizens free of charge!

I have a question about government deficits that never seems to be addressed. We know that the government deficit is exactly the increase in nett financial assets of the private domestic sector plus that of the foreign sector in the currency in question. Continual deficits lead to an accumulation of assets in the non-government sectors. What is the significance of that accumulation and how it is distributed?

Tony,

The net or overall effect of the “accumulation” will presumably be stimulatory. If I find my bank balance to stock of liquid assets has risen, I’m likely to try and spend some of it. How about you?

As to how the accumulation is distributed between rich and poor, and savers and non-savers, it’s hard to say.

As to how its distributed between an increase in government and debt and an increase in the monetary base, that depends on how deficit is carried out. If for example a government did some fiscal stimulus (i.e. borrowed and spent $X) and the central bank immediately created new money and bought the $X of government bonds, the effect would be just a rise in the amount of monetary base, with no rise in govenment debt, except for government debt in the hands of the central bank. But government debt in the hands of the central bank is a near meaningless concept.

Phil, the private sector didn’t decide to net save in 2007. It was forced into it by a combination of tax cuts, government spending increases and interest rate rises.

Economic cycles happen! Whether or not the private sector is net saving, there will be crashes and some investors will lose their money. But crashes need not be disastrous, as governments can quickly increase their spending to compensate.

MMT should support private sector investment instead of trying to impose a desire for the private sector to net save.

And claiming net exporting to be stupid is incredibly stupid! Although what the foreigners pay is worth less to them than what they buy, it’s worth more to us – that’s the nature of trade. Net exporting would benefit us in two ways – firstly it’s deflationary as it raises the value of the currency (and does so sustainably, as opposed to foreign cu rrency borrowing which raises it at the expense of its future value). Secondly it enables us to buy more stuff from overseas should we need it in the future.

Aidan,

I would like to disagree with you, if I may. One of the things I seems missing from your analysis is the fact that budget deficit, to quite a significant extent, is determined by automatic stabilizers. Recognize that if assume discretionary government spending to be 0, budget balance would reflect private sector’s desire to net save. So if, due to structural or other reasons, government budget balance is negative throughout the cycle, government cannot do much to make the budget balanced, unless private sector changes its desire to net save. I believe this is the crux of the argument, i.e. that government cannot choose at its discretion to make budget balanced. Hence, budget deficits in all countries that implemented austerity regardless of governments attempts to move budget to surplus or balance.

Don’t you agree?

Edgaras,

AI cant stop you disagreeing with me (only you have the power to do that) but thre are a few things I would like to point out:

Firstly the automatic stabilizers apply cyclically. If they applied structureally then they probably woudn’t be stabilizers.

Secondly taxation decisions are just as important as government spendingn decisions.

Thirdly, it’s only i n thew trough of the cycle that government can’t do much to balance the budget.

Fourthly, net saving is not usually the desire of the private sector, except at the start of the economic cycle. The rest of the time there’s no such desire, though they can still be forced into it.

“MMT should support private sector investment”

It does. That’s what the Job Guarantee is all about – guaranteeing that demand will be at a particular level, guaranteeing that people will have minimum job skills, guaranteeing that you won’t be undercut by purveyors of slave labour. All of which reduces risk and the perception of risk.

The private sector only invests when it is swamped with demand. In business you don’t spend money unless you have to.

The private sector will invest if, and only if, it sees the colour of solid sales orders.

Neil, you dont seem to have been following what I have written very closely. This is not about getting demand started – obviously increased government spending is the best way to do that. But once demand is high, it’s better to encourage businesses to make long term investment decisions rather than continuing to use public sector deficiets to boost short term demand.

Bill,

I have carefully considered your observation on my earlier comment. My reflections take me back to equation 3 which is

(3) C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M).

You make a valid and important association but you accomplish it by mixing apples and oranges with the terms “S” which is household savings and “T” which is taxes. Clearly, there is no product for either so both are pure monetary terms. All of the other terms can be associated with a product changing hands for money. Apples and oranges have been mixed.

All will agree (I hope!) that product or services have been rendered when government consumes, resulting in the private sector obtaining money to pay taxes and to use for other exchanges, so the term “G” is also product related.

Equations describing apples and equations describing oranges can be added if both are expressed as identities and the identities added. What is needed to make Equation 3 valid is to recognize two identities, government and private. The government identity is G = T + PB where PB is printed/borrowed money needed to balance the budget. The private identity also needs to be changed on the right side because C on the left side includes both the I and (X-M) terms. I suggest recognizing domestic consumption with the term “DC”. Equation 3 should then read

(3) C + S + T +PB = GDP = DC + I + G + (X – M).

Now one of your points was that private savings must come from government deficits. I agree and would prove that by subtracting all the product related terms from the revised equation 3. The resulting equation would be

S + T + PB = 0.

Now this result certainly creates some confusion because savings would equal negative tax plus negative PB. Savings could only be positive if taxes were negative! Well, does not society as a whole actually have negative taxes when government creates money? More money is spent by government than is received in taxes, so yes, a negative tax is being applied to the economy. Your point is proved!

“it’s better to encourage businesses to make long term investment decisions rather than continuing to use public sector deficiets to boost short term demand.”

No it isn’t.

Businesses make investments based on the demand for their products.

You can’t encourage businesses to make long term investment decisions with direct action. You can only subsidise those investments.

In which case the question is why public money is being used to provide certain people with private assets.

What you missed in my reply is the structural change MMT puts forward – known stable demand, known stable workforce conditions, known price of money. It is that stability and security of demand that encourages long term investment decisions – not tax breaks or messing around with interest rates.

Monetary policy primacy by an unelected cabal of technical wizards is a busted flush. It is fundamentally undemocratic. It has had its day.

The way forward is a functional finance approach. Much simpler. Much more direct and, importantly, controlled by our elected representatives in parliament.

Neil, you can encourage businesses to make long term investment decisions with direct action. Cutting interest rates greatly improves the profitability of long term investments.

You can reduce instability, but you can’t make an open economy stable in sn unstable world. Competition from overseas will ensure demand is never stable.

I’m not clear what you meanby “a functional finance approach”. How would you suggest monetary policy is run?

“Cutting interest rates greatly improves the profitability of long term investments.”

Profitability of long term investments depends on demand and the stability of demand over time. In business interest rates are a sideshow.

“Competition from overseas will ensure demand is never stable.”

Competition from overseas is limited by the real exchange ratio in a floating rate system. You are competition from overseas to other countries. If ‘overseas’ tries to get around this by net saving in your currency, then you offset that net saving as you would domestic net saving to neutralise it.

“I’m not clear what you meanby “a functional finance approach””

Bill et al have written endless blogs about it. Check the history ->

Neil, I checked the history and finally found the functional finance piece here, but reading the article doesn’t answer my accompanying question: how do you suggest monetary policy is run?

Competition from overseas is affected by floating exchange rates, but not limited by it. And a floating exchange rate greatly increases instability for individual businesses.

Interest rates are never a sideshow, especially when you consider that demand is price elastic, and new equipment can reduce ongoing costs. If the cost of interest on the loan to finance the new equipment excedes the savings in ongoing costs, it’s just not worth it.

“Interest rates are never a sideshow”

I would suggest some time in the real world learning how businesses actually operate.

“I would suggest some time in the real world learning how businesses actually operate.”

And I would suggest you look at the big picture instead of extrapolating from your limited experience.

“And I would suggest you look at the big picture instead of extrapolating from your limited experience.”

To look at the big picture first you have to see what is actually there, rather than what you want to believe is there.

Some of us can do both.

Both big picture and detail.

The aggregation and disaggregation functions are not that easy to discern.

Neil, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, and claiming businesses ignore the cost of capital in their investment decisions is an extraordinary claim. Admittedly not all businesses do (some dont have to borrow) but on the whole, business managers are not stupid!

But if you really want evidence, look at the fact that interest rates can be used to control inflation.

“Neil, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof”

They do. But these are not extraordinary claims. What you are ignoring is the demand side and the actual dynamics of real business. Real businesses don’t do what you believe they do.

Even in the property business (and I’ve run a sizeable portfolio) interest is a side show. During a run what matters is who you can sell it to. Interest is just a cost like cement on which you apply a markup to get your price. If you can get your price you do the work. That means you can easily have zero activity in a low interest environment and frenetic activity in a high interest environment. It depends on the state of the marketplace.

You’re not seeing that business is primarily a margin game – with a sales side as well as a cost side. And that’s what years of experience studying and helping them tells you.

Interest is nothing more than a tax that you pay bankers. How that tax is subsequently deployed changes the dynamics of the effect at a macro level. It is perfectly possible to increase base rates and fuel a boom – which is what Minsky described so eloquently.

“But if you really want evidence, look at the fact that interest rates can be used to control inflation.”

You believe that interest rates can control inflation. What you actually have is at best a correlation with extremely variable time lag. That’s not a fact. It’s curve fitting to a belief.

I’m with Bill on this one. Interest rates have extremely uncertain distribution characteristics at the macro level. The channels are too complex and too fluid to understand properly in all dynamic situations. The response is too slow.

What we know works are the auto-stabilisers. Give people money and/or take less off them and they spend more and save more. Nice and simple. Nice and democratically accountable.

Difficult to see why you’d want something more complicated and uncertain unless you have an ulterior motive – increasing the return to the rentier class.

Neil, I believe real businesses factor in the cost of interest when they decide whether it’s worth investing in new equipment. To claim they don’t is extraordinary – why would they fail to estimate the profitability of possible decisions?

AFAIK the property business doesn’t invest very heavily in equipment, so saying “even the property business…” is a bit misleading – the effect would be far weaker there than in other industries. But your argument that it’s sideshow is unconvincing. It is indeed a cost like cement, and costs like cement are significant.

Of course interest rates aren’t the only factor that affects business decisions. If you think I’ve claimed othherwise then there’s a problem with your comprehension.

If you regard interest as nothing more than a tax you pay bankers, why wont you support policies to make it as low as possible (subject to demand and inflation limitations)?

Controlling inflation with interest is not a curve or a belief, it’s a phenomenon with a well understood mechanism. Countermechanisms do exist, but has there EVER been a real world example of an interest rate rise actually fuelling a boom?

Interest rates are indeed an inefficient way of controlling inflation, but the do work and Bill has explained why they do. I’d much to have permanently low interest rates, but that would require fiscal policy to be significantly tighter most of the time if inflation is to be controlled.

And I find it quite ironic that you’re accusing me of wanting to increase the return to the rentier class when what I’m proposing would have exactly the opposite effect.

“To claim they don’t is extraordinary – why would they fail to estimate the profitability of possible decisions?”

I’m struggling to get the point across here.

It’s like talking about saving and equating it with saving net of investment. The two are not the same and the dynamics are different.

You can’t talk about costs without considering sales. Sales are not static. It’s sales net of costs that matter.

Minsky showed where excessive private sector borrowing leads and the real world has confirmed that. To continue to champion unstable private sector borrowing at this time is just not a supportable theory. The real world doesn’t work like that.

Found a good explanation for the effect.

People are naturally momentum investors, not value investors.

Neil, ISTM thhe reason you’re struggling to get the point across is because you know the point you originally made was unsupportable, and instead you have been putting a lot of effort into arguing the TOTALLY OBVIOUS point that interest rates are not the only factor in business investment decisions.

Instability is a trivial problem because variations in government spending can easily compensate for it. So is there any non trivial problem with private borrowing?

And while it’s true that people tend to be momentum investors rather than value investors, but I’m wondering what do you think this explains that needs explaining? I hope you agree that unsuccessfully truing to curtail a boom does not constitute fuelling it.

“Neil, ISTM thhe reason you’re struggling to get the point across is because you know the point you originally made was unsupportable”

No I think it’s the usual cognitive dissonance from the private borrowing crowd. You just don’t want to see what is plain to see in the Financial Instability Hypothesis – even though what it states was validated by the biggest financial crisis in decades in the real world.

Little point carrying on here.

Neil, when you say “Interest is nothing more than a tax you pay bankers” but oppose policies that minimize the amount of interest that needs to be paid, that indicates the cognitive dissonance is on your part.

I make no apology for looking at the situation and coming to a different conclusion than you, and I’m happy to discuss the reasons for it. But if you’re not then there is indeed little point in carrying on.

Continuing to fret over this posting by Bill.

Bill is using Keynesian sector analysis and makes a valid association

(3) C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M).

Unfortunately, it appears that the use of “C” on both sides of the equation is fundamentally incorrect sector separation and the identification of S as household savings is misleading. The left side of the equation needs to be carefully reconsidered. We will begin by discarding the left side terms C and S, leaving only T. We will replace both S and C using a different logic.

First notice that the left side of the equation is composed of accounting sums. This is unlike the right side which is terms containing an exchange item times the value of the item. This fact, by itself, is ample to invalidate the use of C equally on both sides of the equation. We do know that the total on both sides is equal.

From inspection of the terms, we can see that two variables of the government identity G = T + PB are present, where PB is the amount printed/borrowed to balance the budget . It would therefore be allowable to add the term PB to the left side of the equation. At this point, the term G is effectively on both sides of the equation. We can therefore write

(3A) G + NGR = T + PB + NGR = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

where NGR is Non-Government Remainder.

The term PB is the money that MMT urges government to spend wisely to reduce unemployment so it is very useful to see the sectors affected. We can rearrange eq. 3A to write

(3B) PB = C + I + G + (X – M) – T – NGR

From eq. 3B we can see that an increase in PB will increase all the positive components more than the negative components but EVERY component can be expected to increase with increasing PB. We have no information here that would show how PB is distributed between the right side terms C, I and (X – M).

The equation does not address the issue of holders of money not using their savings. Only money spent and received is recorded in the GDP calculation, with spent always balanced with received.

For the reasons described, this reader does not consider Bill’s sector analysis to be entirely correct.

Aidan

Two things about what you said in response to my comments:

Firstly, government policy cannot force the private sector to net save. That decision is ultimately made by the private sector. If, following tax cuts, government spending increases, and interest rate rises the private sector responds by increasing its spending out of what would be higher national income, it need not have to alter its net savings desires. It simply chose to increase its net savings because these policy decisions made it easier to do so at a time when private sector debt had risen substantially.

Secondly, you say that net exporting “enables us to buy more stuff from overseas should we need it in the future”. Correct me if I’m wrong, but that means we must net import in future to gain the benefits from trade that you claim. Net exports plus net imports of the same value = net exports of 0! Thanks for demostrating the validity of my point.

Phil, government policy can and did force the private sector to net save. Although it can’t force individual businesses and households to do so, it doesn’t need to. By creating the conditions where the private sector has more money coming in and borrowing is more expensive, the sector as a whole saves more and borrows less. Do that enough and it’s forced to net save, as happened in 2007.

Secondly, net exporting doesn’t imply that it will continue that way for ever, and you have ignored my other reason for it to be worthwhile. Far from confirming the validity of your point, I have refuted it.