The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

One Ferrari does not a recovery make

I thought that blog title today was appropriate given that Aristotle was Greek. Today I explore motor vehicle registrations – well to be exact, a single registration. That is a backdrop to a brief discussion about the OECD’s latest publication – Going for Growth 2013 Report – which takes the ludicrous to a new level. These organisations need to be closed and the cash that governments pump into them to provide very amenable – some would say, over the top – working conditions (high pay, no tax obligations, well supported travel, first class facilities etc) could be diverted into something more useful. Like provide some low-paid workers with jobs. Lets assume one OECD manager earns the same wage as about 20 low-paid workers per week. The trade-off 1 job lost for 20 gained sounds a good bet to me. Anyway, amidst all the talk about structural agendas and reform zeal there is an ugly truth. There has to an easing of the macroeconomic constraint that is preventing economies from generating enough jobs. Firms need to see spending before they will increase production. Making life harder for workers through cuts to wages, conditions of work, pensions and the like will not create a single job. I lie – at least one job. Some OECD official will get assigned the job of evaluating their work and then a renewed bout of lies will emerge clothed in techno-speak. I just know that one Ferrari does not a recovery make. It tells me that the world is turning for the worse.

The quotation from Aristotle, which appeared in Book 1 (paragraph 7) of his – Nicomachean Ethics – written in 350 BC, reads:

For one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one day; and so too one day, or a short time, does not make a man blessed and happy.

There is a debate as to whether the translation is summer or spring but either way, one Ferrari doesn’t a recovery make.

While I was looking into Greece yesterday I updated some data I sometimes look out relating to motor vehicle registrations. A particular snippet in the UK Guardian article (February 19, 2013) – Eurozone crisis as it happened – also reminded me of this data.

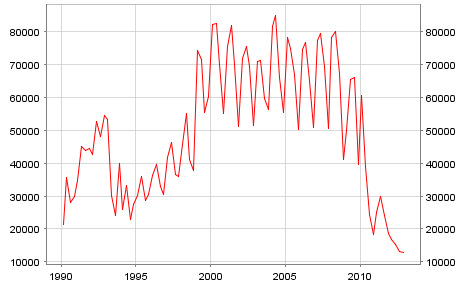

The ECB publish data on – New passenger car registrations in Greece. The latest ECB data shows that there were 12,809 such registrations in the fourth-quarter 2012 compared to a peak of 80,033 in the second-quarter 2008.

A recent report (with even later data) – The Greek automotive market (January 2013) – says that:

Passenger car sales in the crisis-stricken Greece are in a free-fall as the market continued to plunge in January 2013 due to considerable flabby buying interest. Even though the withdrawal program has been extended until the end of 2013, passenger car market posted 5,533 registrations compared to 8,451 in January 2012, paving the way for another year of sluggish sales.

Here is the graph of the ECB data going back to 1990:

Well according to data provided by the Greek Association of Motor Vehicle Importers Representatives – only one person in Greece, in Macedonia, registered a Ferrari in 2012.

An examination of the same data for 2007, just before the crisis hit shows that there were 21 new Ferrari registrations in Greece. How the mighty have fallen.

And then I saw that the OECD released its latest estimates of the national accounts for its bloc, which showed that the advanced nations are going backwards again.

And – Latvia is lining up to walk the plank with the other Eurozone nations. Is this all real?

The OECD released its – Going for Growth 2013 Report – last week (February 15, 2013) at a time when the the richest nations are contracting.

It is the same old story and claims the policy framework proposed:

… builds on OECD expertise on structural policy reforms and economic performance to provide policymakers

Which is like saying that the IMF is good at forecasting expenditure multipliers. The OECD has an appalling record.

Please read my blog – The OECD should close and its staff redeployed into productive activities – for a discussion of how the OECD lost its way after beginning life as a progressive institution hat well understood the role that activist fiscal policy played in promoting stable growth and full employment.

Now it is just another over-funded, cosy mouthpiece promoting neo-liberalism.

Its masterpiece of the 1990s – the 1994 Jobs Study agenda – has been the principle policy framework since the early 1990s and has promoted privatisation, deregulation and massive welfare changes all aimed at weakening trade unions and making the most disadvantaged workers more desperate.

Their endorsement of inflation-first macroeconomic policies where monetary policy plays the prominent role and uses unemployment to discipline the inflation generating process and fiscal policy is largely contractionary has left a legacy of persistently weak growth, entrenched high unemployment and rising underemployment.

Over the last 20 years or so, many academic studies sought to establish the empirical veracity of the orthodox view promoted by the OECD that unemployment rose when real wages and workplace protections increased. This has been a particularly European and English obsession. There has been a bevy of research material coming out of the OECD itself, the European Central Bank and various national agencies, in addition to academic studies.

The overwhelming conclusion to be drawn from this literature is that there is no conclusion. These various econometric studies, which have constructed their analyses in ways that are most favourable to finding the null that the orthodox line of reasoning is valid, provide no consensus view as Baker et al (2004) show convincingly.

In the last 10 years, partly in response to the reality that active labour market policies have not solved unemployment and have instead created problems of poverty and urban inequality, some notable shifts in perspectives are evident among those who had wholly supported (and motivated) the orthodox approach which was exemplified in the 1994 OECD Jobs Study.

In the face of the mounting criticism and empirical argument, the OECD began to back away from its hard-line Jobs Study position. In the 2004 Employment Outlook, OECD (2004: 81, 165) admitted that “the evidence of the role played by employment protection legislation on aggregate employment and unemployment remains mixed” and that the evidence supporting their Jobs Study view that high real wages cause unemployment “is somewhat fragile.”

Then in 2006, the OECD Employment Outlook entitled Boosting Jobs and Incomes, which claimed to be a comprehensive econometric analysis of employment outcomes across 20 OECD countries between 1983 and 2003 went further. The study sample for the econometric modelling included those who adopted the Jobs Study as a policy template and those who resisted labour market deregulation. The Report revealed a significant shift in the OECD position. OECD (2006) found that:

- There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

- The level of the minimum wage has no significant direct impact on unemployment; and

- Highly centralised wage bargaining significantly reduces unemployment.

OECD (2006) found that unfair dismissal laws and related employment protection do not impact on the level of unemployment but merely redistribute it towards the most disadvantaged – including the youth who have not yet developed skills and have little work experience.

These conclusions from the OECD in 2006 confounds those who have relied on its previous work including the Jobs Study, to push through harsh labour market reforms; retrenched welfare entitlements; and attacks on the trade unions. It makes a mockery of the arguments that minimum wage increases and comprehensive employment protection will undermine the employment prospects of the least skilled workers.

But this point is obvious. In a job-rationed economy, supply-side characteristics will always serve to only shuffle the queue. But you cannot say that the unfair dismissal laws and related employment protection have caused the unemployment! The problem is that there have not been enough jobs overall.

Now, after one of the worst recessions (and in Spain and Greece at least Depressions) in history the OECD has crept out of its rat hole and are reasserting its claims that structural impediments are the reasons economies cannot grow.

I recall the debates of the 1990s that accompanied the release of the Jobs Study. All these mainstream economists were arguing that the rise in mass unemployment was due to structural issues – excessive replacement ratios, tax wedges (on-costs etc), minimum wages, and the rest of it. The problem was that when unemployment rose sharply – at a time when aggregate demand growth collapsed – none of these so-called structural impediments moved.

But that didn’t daunt them then. And it is certainly not going to daunt them now. They are back in full swing advocating a continuation of the supply-side agenda when it is clear that it is job creation that is necessary.

In one passage of the latest document we read:

Measures in the areas of employment protection legislation, wage bargaining institutions and the minimum wage, which are recommended to improve employment opportunities for low-skilled workers and young people, may widen the wage distribution and thus exacerbate income inequality in the short run. This effect, however, may be partly or even fully offset in the longer run as job prospects brighten for such workers, especially those weakly attached to the labour market

This is the myth that they spin regularly. Cut wages, job protection, allow firms to use unpaid labour as “work experience”, take trade unions out of the picture and firms will hire more.

Yes, they admit that income inequality rises but that is just a “short run” effect, which will be reduced because more people have work.

The reality is very different. First, it is unlikely that more people will get jobs. Refer back to their admissions in 2004 and 2006. They seem to have forgotten what their own research told them.

Second, creating more low paid precarious jobs that have had their security stripped doesn’t reduce inequality. It just means more workers are in casualised,go-nowhere jobs helping sustain an increasing profit share.

Third, unemployment is the result of a macroeconomic constraint (as per the first point). Even if labour is cheaper firms will not employ them if they cannot sell the products that the workers might produce.

The mainstream argument is that if wages and prices are lower there will be more spending via real balance effects (the money holdings become more valuable at lower prices). The empirical evidence for this theoretical effect suggests that if real balance effects exist their impacts are tiny.

Fourth, low wage societies have lower productivity. The OECD agenda is about a race to the bottom and should be avoided.

The cure for mass unemployment is not to cheapen labour and make jobs more precarious. It is to close the spending gap with increased aggregate demand. If the non-government sector doesn’t want to come to the party then their is only one sector left that can – it starts with G.

But the OECD just reinforce the view that government fiscal expansion is now exhausted. We read statements such as:

The need to put public budgets on a sustainable path

Where were they not sustainable? Is Japan in an unsustainable path? How long is the path? They were saying 20 years ago that the Japanese government would collapse under the weight of its public debt.

The debt has accelerated, the deficits grown but still no collapse! Bond yields are low, there is a queue of institutions etc eagerly awaiting each bond auction. When it the path going to end?

Is Iceland on an unsustainable path? The OECD criticise Iceland for making no progress in implementing the OECD’s damaging reform agenda:

Despite exposure to financial market scrutiny, Iceland and Slovenia have made no or very little reform progress in the areas identified in 2011.

No they did better than that. They kicked out the banksters, refused bullying demands from the Netherlands and Britain to socialise the losses of their criminal private financial market players, and sought to stabilise domestic growth.

Maybe the Eurozone? Where the design of the system means that any reasonable cyclical response from the automatic stabilisers is sufficient to render the budget “unsustainable” relative to the arbitrary and meaningless Maastricht treaty fiscal rules.

Of-course budgets are unsustainable if we define them to be so. The question is whether the definition makes sense in the case of the Eurozone. The answer is that there is no sense in the fiscal rules.

But wouldn’t the bond markets punished Greece if their deficit was larger? Perhaps although the larger deficits would have driven growth. But even if the bond markets turned on Greece that is not a reason for using deficits to support growth and put an end to the bloodletting.

Why not? Because the bond markets are mendicants. Yes, the Euro nations have to fund their net spending because they use a foreign currency. The best thing would be for them to restore their own currencies.

But given they haven’t shown a willingness to do that, the next best thing would be for the ECB to behave like a central bank for once and formally fund the deficits.

But that is against the Treaty isn’t it? Perhaps but they have found ways around that anyway. The ECB has demonstrated that it can take the bond markets out of the equation – for example, the Securities Markets Program (SMP) where they purchased government debt in the secondary markets. Same end basically.

But didn’t they impose austerity as part of their willingness to buy that debt? Answer: they did but the real question is whether they had to do that. The Answer to that question is that they didn’t have to impose austerity as part of their commitment to keep some of the nations afloat financially.

In fact, they should have announced to the world that they were funding increased deficits in search of growth and the member governments could have then announced employment programs, boosted pensions and put spending power into the hands of the poor.

The crisis would have been over within 6 months.

Yes, there are economists (count me as one) who know that deficit spending – when there is insufficient non-government spending – will stimulate output and employment growth. Deficit spending won’t solve “all our problems” and as far as I know no-one associated with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) would be stupid enough to make that statement.

They would have to be as stupid as anyone who might suggest we thought that.

The OECD also say:

Yet, given the weakness of near-term demand prospects, the limited scope for macro policies to further stimulate demand …

Weakness is euphemistic. Some nations are in Depression. There has been a collapse in spending and there won’t be a recovery for years. The OECD is always talking about “short run” damages or “near-term” problems as if they will wave their structural wand and the problem will be solved.

Many nations are caught up in a grinding downward spiral as a result of them abandoning the use of the best policy tool they have – fiscal policy – in favour of the nonsensical approaches proposed by the OECD and its ilk.

There are millions of people unemployed. That is a lot of scope for macroeconomic policies, which are only limited among currency-issuing nations by the availability of real resources.

Governments could announce wide-spread employment initiatives and then we would see the true scope of demand stimulus. I guess if we rule out most of the things that fiscal policy can achieve on ideological grounds then there isn’t much scope left eh!

Conclusion

All of this was in the context of the admission by the OECD reported in the UK Guardian article (February 19, 2013) – OECD economies shrank at end of 2012 – that the:

The world’s richest countries saw their economies contract for the first time in almost four years during the final three months of 2012 … gross domestic product across its 34 member states fell by 0.2% – breaking a period of rising activity stretching back to a 2.3% slump in output in the first quarter of 2009.

All the major economies of the OECD … have already reported falls in output at the end of 2012, with the thinktank noting that the steepest declines had been seen in the European Union, where GDP fell by 0.5%.

The “going for growth” agenda is a sick joke.

I wonder who registered that Ferrari?

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

To what extent is the nonsense elaborated above and pedalled by the OECD, IMF, World Bank etc a gigantic con trick (deliberate lying for the purpose of achieving a hidden agenda), and to what extent are they true believers – prisoners of their own spin?

Everybody is a prisoner of their own spin.

Greek oil & gas consumption (capital) is more valuable to the core then Greek labour.

Therefore you don’t want to give them cars if you are a euro freak.

You can clearly see this in IEA Oil & gas reports for Europe.

With French & German Nat gas consumption up slightly this year (to November) while the rest of the lot including the Netherlands tanking.

Diesel consumption (work) in the core also holds up relative to the edge.

However Dutch car consumption is down 31.2 % in Jan relative to Jan last year.

Only a months data but I suspect this is a result of the banking nationalizations there.

The Euro is not a nation state token.

Its a shared capital token.

Labour does not really come into the equation unless it can be snuffed out.

If you want to see how Europe works look at Lithuania

Eurostat energy production and dependence rates 2008 -2011.

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/8-13022013-BP/EN/8-13022013-BP-EN.PDF

Lithuania has gone through what appears a second post Soviet collapse with the closure of its unit 2 reactor in dec 2009.

A 24.5 % collapse in consumption is major war stuff.

Lithuania import dependence was 51.2 % in 2009

81.8 % in 2011

Wow !!

This is a HUGE difference.

So despite a collapse in consumption its import dependence reached almost Irish levels after shutdown.

Germany is in a very poor energy dependence position.

Almost as bad as Greece.

Greece Y2009 : 67.8 %

Y2011 : 65.3 %

Germany Y2009 : 61.6 %

Y2011 : 61.1 %

Not much of a improvement despite the much vaunted energy fetishes that Germany gets up to.

2012 is likely to be much worse for Germanys import dependency given their Nuclear shutdown policy.

It may indeed reach Greek levels soon !!!

Why ?

Germany is a entrepot economy – perhaps the most extreme example in the entire European entrepot.

In contrast France seems much more successful for the moment (although some factions within the socialist party wish to shut down the French nuclear programme also)

French energy import dep.

Y2009 : 51.3 %

Y2011 : 48.9 %

This is a result of the foundation like sci -fi islands it has built. on the backs of the Greeks ? as well as falls in car consumption although before the second major almost 2009 like falls of 2012.

Ireland however has increased its dependence despite epic falls in consumption.

Y2009 : 88%

Y2011 : 88.9 %

The Euro will always seek to replace capital with more capital

It will never seek to replace capital with labour.

Which means core (energy) capital must be reduced – however efficiently it is burned.

I.e the Euro region is incapable of creating net capital.

Lithuania had a skilled nuclear workforce once.

Why did not Europe provide the funds to replace the reactor thus preserving wealth and the workforce ?

I actually worked with a girl who came from the Lithuania nuclear town.

According to her the closure of unit 1 (unit 2 had yet to come) had devastated the town & apparently the national economy.

OK it was a dangerous reactor but the EU never gave them the resources to built a modern PWR – given the nuclear labour expertise of the area it was a no brainer.

They are not very politically aware people – the elite within the west just saw them as units to drive down their domestic labour costs / extraction of labour value so there was no need to invest in the region.

Their workforce was more valuable to the fat controllers of the west………….so you ship them west so as to drive down unit labour costs in the richer western countries.

Its as simple as that I am afraid.

Slightly OT, but had to post … but, but, but … all those reserves …

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-20/jpmorgan-leads-u-s-banks-lending-least-of-deposits-in-5-years.html

My feeling is they all go along with the rubbish to maintain their group identity. I doubt they any have strong convictions believing in their own sh1te or not. Like any modern organization they have been conditioned to smile and say “yes masser”.

Maybe there are a few sociopaths at the top who are genuinely evil. Perhaps there are some decent men who question in their minds but keep their traps shut to hold down a job.

As a manager in a typical large corporation I felt obliged to smile and repeat the same CEO’s crappospeak every day. I did it because I wanted a better future for my family. When my kids left school I couldn’t take it any more and left without a job to go to. I’m poorer but happier.

John Hermann,

I never underestimate the capacity for humans to convince themselves of total shlock. Bet you to a man and woman they believe what they’re printing.

Hi Bill,

could you in some blog post examine and critice this tax wedge concept? Here in Finland lowering tax wedge has been THE overarching policy goal of all governing political parties for the last 20 years, on the unassailable logic that if you tax working heavily it will discourage working. So they have constantly shifted taxation from income taxes elsewhere mainly on value added tax. As if VAT were not part of the normal company-worker-company spending cycle.

But VAT and various other consumption taxes and environmental taxes are regressive relative to income while income taxes are progressive. Finland is at the top spot in the income inequality growth of OECD countries. Not to mention that shifting taxation from incomes to consumption will leave that part of the income that goes to savings untaxed and so encourages saving, which is perverse when we are suffering from not enough spending but god know what they are thinking.

This policy agenda has driven raising the income taxes a tabu, so I think taxation has shifted for the worse. Various consuption taxes and they even started to tax car ownership. Taxing ownership – does it make any sense? You can avoid tax by not owning anything but then what is the point of that tax? People are poor and state do not get tax revenue. Artificial poverty in the mids of plenty.

So yeah this tax wedge concept needs challenging and Bill could kindly examine it I could then update it’s wikipedia entry.

Gangsters ……….

http://dublinopinion.com/2013/02/20/reits-and-the-irish-state/

They will only inflate when they have the conduit assets.

Bill will not accept that we are dealing with a very deep & old money cartel.

“Sov” Australia is just in a different part of the cycle.

Its the same guys in the same sister CBs.