The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Spain is not an example of reform success

There was an article in the Financial Times last week (February 12, 2013) – Europe’s labour market reforms take shape – that claimed that Spain was on the path to glory by hacking into rights of its workforce (that is, the 75 odd percent that still have jobs). It followed another Financial Times article (February 11, 2013) – Productivity is Europe’s ultimate problem – written by the deputy managing director of the IMF and redolent of the ideology that organisation spins as facts. Both articles are part of a phalanx in the conservative press that prefer to lie rather than relate to the facts. Apparently we have a new poster child – Ireland was the first one (now forgotten as it wallows in the malaise of fiscal austerity). Now, Spain is the go – a model for savage labour market reform and export led growth. Well it is a model – for how to ensure the unemployment rate and poverty rates continue to rise and you produce an economy that stops employing its 15-24 year olds. Some poster child! Spain is not an example of reform success. Rather, it demonstrates how misguided the policy debate has become and how a policy devastation is now being seen as good. Truly bizarre.

The IMF inspired article started with the authoritative claim that:

It is now widely accepted that managing the eurozone crisis requires “more Europe”. Greater integration is needed not just for the sake of the single currency, but also across the single market of the EU to improve competitiveness and revive economic growth.

My alarm bells always ring when I read “it is now widely accepted” as if we are all in agreement. Agreement about what? What is more Europe? A fully federated fiscal system with the central government (fiscal authority) able to appoint the board of the central bank and transfer funds to the “states” to maximise public purpose?

That capacity, which is the only structure that makes sense in a singe currency “nation” is definitely not “widely accepted”.

According to this IMF official, the “primary cause of the crisis”:

… was the lack of convergence in productivity.

That is total revisionism.

The primary cause of the crisis was that the Eurozone received a major negative aggregate demand shock that constrained economic activity. The shock impacted asymmetrically across the zone reflecting, in part, the different spatial composition of industry across the industry. But it also reflected different levels of indebtedness (largely tied to pre-crisis real estate developments).

What was required to meet the crisis of spending was a stimulatory budget response to replace the lost non-government spending. The fiscal rules that were imposed on member states by the Maastricht Treaty and later agreements meant that the individual states could not respond adequately and were forced by the elites (who had an ideological investment in those rules) to impose fiscal austerity at a time when stimulus was required.

There was no federal fiscal capacity to then take on the necessary stimulus function. The absence of that capacity was a deliberate choice by the founders of the Eurozone. They intended to limit the capacity of the state as part of their neo-liberal predilection. That preference has back-fired dramatically.

It was always going to back-fire, given that it was not founded in sound economic policy design but rather reflected the crude anti-government zeal that pervaded at the time as well as a dramatic level of ignorance about the way monetary systems operate.

Then we are told by FT columnist Tony Barber (Europe’s labour market reforms take shape) that “Spain is leading the way with the pace of economic change” – I would agree with that statement if the economic change intended was to see who could achieve the highest jobless rate while maximising the youth unemployment rate. Spain is excelling on that front.

But that is not what the FT intends to convey. The article says that the structural reforms in Spain are working:

Even the thousands of extra jobs created by the new investments in Spain’s car industry will not make much of a dent in the national unemployment rate of 26 per cent. But they are a sign that the Spanish economy, laid low by a construction and property boom that felled its banks and drove sovereign debt yields to perilous highs, is adjusting at a remarkably fast pace.

Much of this stems from a 2012 labour market reform that gave companies the upper hand in setting wages by revising a collective bargaining system based on national, regional and sectoral agreements between managements and unions. Spanish productivity is up 11 per cent since mid-2008, exports are at record levels and a current account once redder than a vintage Rioja is heading into surplus.

This is only a half truth. The article notes that “(p)art of this success” in the current account shift “is down to a sharp squeeze on imports that will not last once Spain returns to economic growth”.

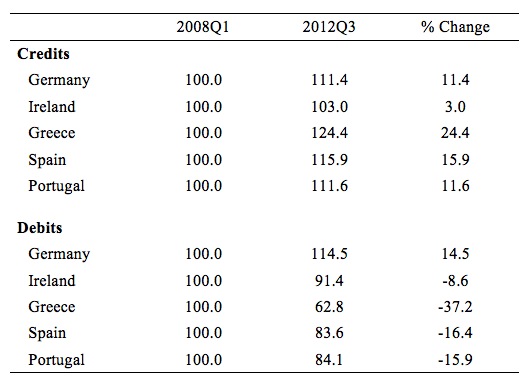

Focus on the impression invoked by the use of the phrase “part of this success”. The following Table is compiled using Eurostat Balance of Payments data. I indexed the credit and debt-sides of the Current Account balances to 100 in the first-quarter 2008 (more or less when the crisis broke out). The Table shows the percentage change in the credits (broadly exports) and debits (broadly imports) up until the third-quarter 2012.

The facts are as follows:

1. German credits grew by 11.4 per cent over that period while debits grew by 14.5 per cent indicating a slight decrease in the current account deficit from its very large levels. The growth in imports signals that national income has not been falling.

2. Ireland, the restructuring poster child and the earliest to invoke fiscal austerity (be bullied into more the point) saw credits grow by 3 per cent but debits fall by 8.6 per cent. So the major reason for the current account decreasing is the collapse of imports, which is directly due to the collapse in national income.

3. Greece – credits grew by 24.4 per cent but debits declined by 37.2 per cent indicating a huge drop in national income and material standards of living.

4. Spain – the so-called leader of the new leaner Europe – credits grew by 15.9 per cent (so not much better than Germany) but debts fell by 16.4 per cent, again indicating that the current account shift is mostly down to a collapse in imports as national income has fallen.

6. Portugal – same story.

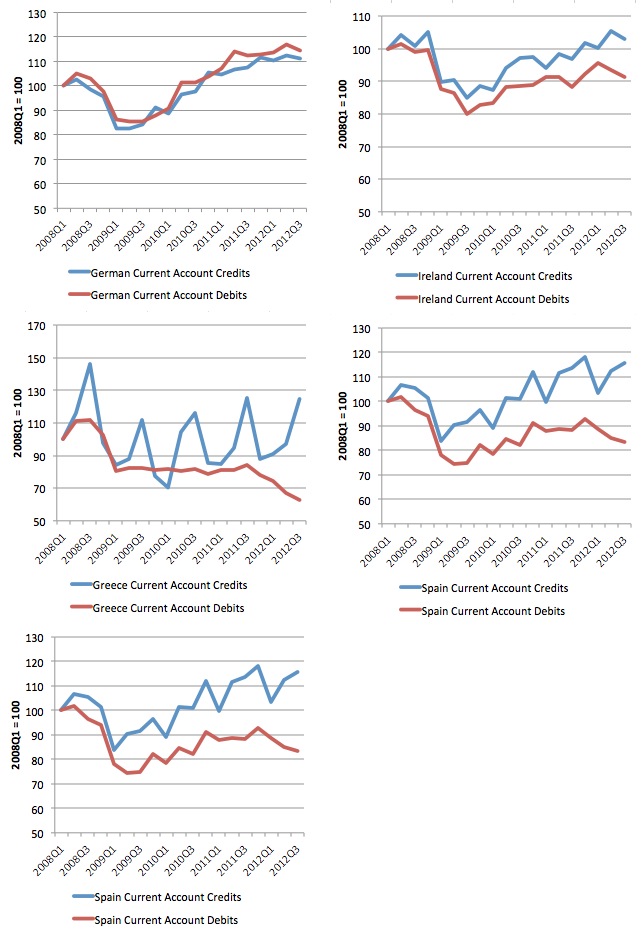

The following graph shows the indexes for credits and debts over the time period – 2008Q1 to 2012Q3 – to help you understand that for the southern European states and Ireland, the so-called restructuring is only manifesting as decreases in current account deficits because of the collapse in imports.

The latest trade data supplied by Eurostat (February 15, 2013) – Euro area international trade in goods surplus of 81.8 bn euro – doesn’t exactly support the export-led recovery story.

In December 2012, total exports fell in the EU27 by 1.9 per cent. Specific cases include: Ireland -3.7 per cent; Greece -3.1 per cent; and Spain 0.0 per cent growth in exports in December 2012.

On the other side of the trade account, total imports fell in the EU27 by 1.6 per cent resulting in an increase in the trade balance from 3.8 billion Euro to 4.2 billion Euro. Specific cases: Ireland -35.3 per cent ((balance from 2.0 billion Euro deficit to 2.3 billion deficit)); Greece -20 per cent (balance from 0.9 billion Euro deficit to 0.6 billion deficit); and Spain -3.3 per cent (balance from 2.6 billion Euro deficit to 2.3 billion deficit).

These are hardly a sign of an impending boom in trade.

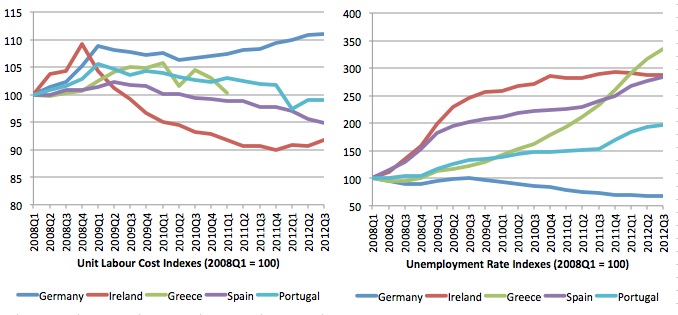

Going back a step I updated my databases today for unit labour costs – which incorporates wage movements and labour productivity.

Nominal unit labour costs tell us how much each unit of output costs in terms of labour input. Given that the labour input is typically the largest component of costs and all nations in the Eurozone face the same exchange rate, movements in relative unit labour costs are one indicator of how competitive one nation is against another. We also have to take into account relative movements in inflation to get a complete picture of shifts in international competitiveness.

Total labour costs in production – the wage bill – is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (w) prevailing at any point in time. Stocks (L) become flows if it is multiplied by a flow variable (w) = w.L

Labour productivity (LP) is the units of real GDP per person employed per period – LP = GDP/L

Unit labour cost are defined as total labour costs divided by total real output:

ULC = w.L/GDP

Note that we can write the right-hand side as w.(L/GDP) and the term in brackets is the inverse of labour productivity (units of output per unit of labour input).

So ULC = w/LP

The problem then arises when we try to interpret the ratio. Like all ratios, ULC can fall because, for example, w rises < LP rises or w falls > LP falls

In English, ULC can fall if the rise in the money wage rate is less than the growth in labour productivity. Equally, unit labour costs can rise if the decline in wage rates is more than offset by a decline in labour productivity.

The two situations present quite different scenarios in terms of prosperity.

The following graph shows movements in unit labour costs since 2008Q1 (indexed to 100 at that point) until 2012Q4 on the left-hand panel (for Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain and Portugal) and the corresponding movements in the unemployment rates (also indexed to 100 at 2008Q1) on the right-hand panel.

This is a game of following the coloured lines down in the left-hand panel and the up in the right-hand panel until you get to the blue line and then you go the opposite direction and ask yourself – what the f?

There was an article over the weekend in the UK Guardian (February 17, 2013) – Spain’s labour reforms won’t bring growth or reduce unemployment – which was in response to the Financial Times analysis I presented about Spain.

There is a lot that is correct about the Guardian response.

The author (Bob Hancké) says:

An old spectre is returning.

The spectre is that a nation can achieve prosperity by cutting wages growth and decimating job security and the supporting welfare system. That is the dream that conservatives suggest to us but never tell us that, in reality, such a strategy doesn’t deliver prosperity but serves to redistribute national income from the poor to the rich.

The author rightly notes that:

Spain’s unemployment rate is 26%, and not falling particularly rapidly. The current account deficit is falling, less as a result of increased exports and more because imports fell dramatically as domestic demand collapsed in the wake of the housing and financial crisis. It is unclear if growth will pick up enough in the short run to avoid a rise in the debt-GDP ratio. So much for economic performance.

Which is consistent with the data I have presented above.

The Guardian article notes that whenever there is an economic crisis “wages are always seen as the problem – even in a financial catastrophe-induced economic crisis”

Mass unemployment is not the result of excessive wage rates (real or nominal). When there is a sudden rise in unemployment (as depicted in the right-hand panel above) it is always the result of a collapse in aggregate demand (spending).

Shifts in the labour market like that do not occur because one nation is more or less competitive in trade than another or because welfare benefits are too high (relative to what?).

They occur because firms can no longer sell the volume of goods and services because spending declines.

As the Guardian article notes:

There may be good grounds to reform labour markets … Workers and skills may have to be matched more closely with the demand for them. Some groups of workers may be exploiting their (near) monopoly in the labour market. Willing workers may not always know of and have access to the available jobs. And countries such as Spain (may) have a particularly nasty dual labour market – with well-protected insiders and weak, usually unemployed, outsiders – which requires adjustment so that more unstable work will lead to stable jobs.

All or some of the above. I would improve protection for workers, raise minimum wages, force employers to offer better skill development and more.

But alone, as the Guardian article notes, none of these reforms will “lead to growth”.

The writer posits that “Aggregate unemployment falls, all other things being equal, when economic growth outstrips productivity growth”. Which isn’t exactly true unless he is holding labour force growth at zero.

The correct statement is if hours of work are constant then the aggregate unemployment rate will fall if real GDP growth outstrips the sum of labour productivity growth and labour force growth.

The former (labour productivity growth) reduces the labour required for given output levels while the latter (labour force growth) adds workers to the queue that real GDP has to generate jobs for.

The Eurozone situation at present is that labour productivity growth is rising as the high costs operations (“very weak companies”) are being expunged. But growth is still going backwards and as a result unemployment continues to increase.

The latest national accounts data released last week (February 14, 2013) – Euro area GDP down by 0.6% and EU27 down by 0.5% – tells us that real GDP growth fell by 0.6 per cent in the fourth-quarter 2012. After failing to grow at all in the March-quarter 2012, real GDP growth then fell by 0.2 per cent in the June-quarter, by 0.1 per cent in the September-quarter and accelerated to fall by 0.6 per cent in the December-quarter.

Where is this export-led recovery?

Spain’s contraction accelerated over the course of 2012: First-quarter 2012 (annualised) -0.7; second-quarter -1.4; third-quarter -1.6 per cent; fourth-quarter -1.8 per cent.

It is a preposterous lie to insinuate that things are on the turn for the better in Spain or the other nations that have been subjected to fiscal austerity.

As the Guardian article correctly notes:

Labour market reforms of this sort do not do much more than redistribute the (possibly fewer) available jobs. For every job in the “competitive” Spanish car industry, read one job gone in the French, Italian, Belgian, Swedish or German car industry. Beggar-thy-neighbour policies of this kind never increase the number of jobs, as Keynes pointed out more than 75 years ago. We should not fall into that trap again.

They also ensure that real income in each nation is being redistributed to profits away from wages.

I also remind readers that an export-led growth strategy is never going to succeed when domestic demand is being savaged by a combination of private spending caution and fiscal austerity. I explain that argument in this blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition.

Conclusion

There is a lot to be said for the substantive message in the Speech – Looking Forward: Social Investment as a way out of the crisis – presented by the László Andor, who is the European Commissioner responsible for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion to the Eurofound Forum in Dublin on February 15, 2013.

Dr Andor said:

The monetary union must be able to collectively address the key employment and social problems facing it.

This requires that fiscal objectives are reconciled with employment and social ones. In practice, this also means that fiscal coordination should be supported by fiscal transfers, if these are needed to enable Member States to undertake structural reforms that will help restore growth and jobs.

That is, the problem is principally a macroeconomic failure to create enough jobs, which has arisen because non-government spending has collapsed and not been offset by a rise in budget deficits.

That failure has nothing to do with productivity or trade imbalances or the extent and generosity of the welfare systems in any of the Eurozone nations.

The Eurozone might want to reform its welfare system by ensuring that the poor are given adequate support and there is an absence of corporate welfare and high-income earner welfare. They might want to introduce legislation to support stronger trade unions to ensure the bargaining environment is more equal than it has been. They definitely should reform the banking system to ensure that banksters who breach the public purpose role of their organisations go to jail.

But the most urgent reform is to scrap the fiscal compact and associated Maastricht fiscal rules and compel the ECB to fund deficits up to the level that supports full employment. At the same time they should be introducing a genuine fiscal federation.

Neither of the latter reforms will occur which means the Eurozone will continue to fail as a monetary system. It cannot deliver prosperity to its citizens under its current structure. Targetting pension systems and wages and conditions is just another neo-liberal smokescreen design to prolong the hegemony of the Brussels-Frankfurt elites.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I gave up my subscription to the FT after a short time when it became obvious to me that Martin Wolf was being gagged by his employer. He knows full well the mechanics of the British (and other fiat) monetary system and the implications for democratic public purpose, yet was pandering to the propaganda line that monetary sovereigns depend on private bond markets to “fund” budget deficits. Don’t know if he’s since changed his tune. Don’t care. Here we have (gratis!) the analysis of a top notch macroeconomist, unhindered by corporate doublespeak.

Jonathan,

Take another look at the FT – Martin Wolf in particular. If anyone is prepared to be unconventional it’s him. I’m surprised at him saying “monetary sovereigns depend on private bond markets to “fund” budget deficits.” But then again, newspaper journalists spew out any old rubbish to keep themselves employed.

This article of his (link below) is pretty unconventional and against the establishment view. In particular, he askes what the state is doing standing behind private banks’ money creation activities. He says “Why should state-created currency be predominantly employed to back the money created by banks as a byproduct of often irresponsible lending?”. See:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9bcf0eea-6f98-11e2-b906-00144feab49a.html#axzz2LDltfstp

Dear Bill

You wrote in Fact 1. that Germany experienced a slight increase in its current account deficit because credits increased by 11.4% and debits by 14.5%. It would have been more accurate to say that there was a slight DEcrease in Germany’s huge current account surplus.

Most countries can’t have export-led growth. Apart from the fact that here we have another fallacy of composition since a world-wide increase in exports also means a world-wide increase in imports, which must lead to considerable disemployment effects in import-competing sectors, there is simply the reality that many countries can’t export that much. Can Spain really export enough to put all its unemployed people back to work? The best policy is always to stimulate domestic demand, unless we are talking about countries like Haiti, which have to import nearly all their manufactured goods. Export-led growth only makes sense when a country has to import a lot of essentials.

Regards. James

I am surprised that Billy wants the ECB to do anything.

“But the most urgent reform is to scrap the fiscal compact and associated Maastricht fiscal rules and compel the ECB to fund deficits up to the level that supports full employment. At the same time they should be introducing a genuine fiscal federation”

No thanks.

Their long term monetary malice has created a Europe with absurdly long supply chains all so as to avoid labour value – thus creating huge externalties which have now gone negative relative to the supposed benefits of globalization.

Europe is now just one big Amsterdam like entrepot economy with no nation state redundancy.

A predictable outcome.

I would of course go further and like to see the destruction of nation state systems to be replaced by a single treasury and no CB but that would be too much to ask for I guess.

Anyhow the last thing Europe needs is a God like central bank to push resources even further upwards.

These men of the temple are evil and there is just no getting around that fact.

Belgium & the Congo comes to mind.

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-12-051/EN/KS-SF-12-051-EN.PDF

But what if the Congo disappears into the political ether – what then ?

Europe can never become a Nation state.

Just as the US was / is a failed market state.

They want to build a bigger better US of F$£king A

A nightmare Dystopian world.

At least up until the 1960s both Ireland & Spain has redundant Agricultural economies although under monetary control of the banking priests.

Now the priests have both control of the physical energy systems and the claims on those energy systems.

A nightmare world.

Take the field away from the peasant and he becomes a serf.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qk-03oFgvyQ

What is happening with the European left outside of Greece? Is it gaining any traction at all? Can someone direct me to a status report?

It seems to me that left mobilization during the crisis in Europe and the US has been crippled by two versions of the same problem. The potential for unity among the middle class, working class and the poor has been wrecked by successful divide and conquer strategies: specifically aimed at immigrants (in the US, Mexican immigrants, and in Europe Middle Eastern immigrants), but also dividing working people against beneficiaries of social welfare programs, the unionized against the non-unionized, and public sector unions against private sector unions.

Even more ‘radical’ Martin Wolf Article:

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/ae8b292a-6fc4-11e2-8785-00144feab49a.html#axzz2KnwrYYdn

Likewise. Although it was probably the 20 per cent hike in monthly subscription price that did it for me.

Apart from Alphaville and the occasional interestng article the FT is ‘mostly harmless’ and in my view certainly not worth the money.

Thanks Ralph Musgrave, it was refreshing to read. I should have made clear that I was referring to 4-5 years ago. It seemed that the most important type of bias exhibited by the newspaper was its manner of framing economic analysis. “When did you stop beating your wife?” was brought to my mind by its treatment of the allegedly imminent high inflation and the evils of fiscal deficits. These weren’t really Wolf’s sins, though he saw the need (or was forced?) to constantly pay homage to such pieces of holy writ.

Thanks SteveK9 – it seems that Mr Wolf is perfectly prepared to call out the Emperor (the MPC) for having no clothes, even though he is a constituent part of it.

Andy, I knew I wasn’t alone. Yeah, Alphaville can be interesting and/or useful. I used to like some of Willem Buiter’s work too. Cheers all.

I stopped reading FT one second after they implemented the pay wall. Reducing their significance to a fan boy magazine for the converted.

Ever since I’ve grasped MMT, I can hardly stomach a whole paragraph of mainstream slop.

@ Dan Kervick

The ‘bad baby boomers’ narrative in the US strikes me as being part of the same strategy.