The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Increase minimum wages and give job guarantees for the low paid

I lived in the North-West of England for a time in Lancashire as I pursued my PhD at Manchester University. It was during the UK Miners’ Strike 194-85, which was in response to the Thatcher Government’s attack on the major unions in the UK to further its ideological war on workers’ rights and welfare provision. The union lost dramatically after a struggle of 12 months symbolising the rise of neo-liberalism. The same ideology that sought to undermine the rights of workers also led to policy changes that, ultimately, caused the financial crisis and on-going real recession. The reason I raised that experience is because I read a report from a Manchester research organisation over the weekend which highlighted a major problem in that region (poverty wages etc) but also, without stating it, provided an alternative policy approach to the current crisis which would quickly get economies moving again – creating jobs and enhancing the capacity of households to spend. A policy response that antithetical to what is being tried at present is to increase minimum wages and introduce employment guarantees for the most disadvantaged workers whose welfare has been disproportionately undermined by the crisis. That would not only help alleviate the major problem at present – deficient aggregate demand – but also redress some major equity issues that the crisis has accentuated.

The strike made it hard for households (like mine) which depended on coal for heating and hot water to cope through the harsh winter. But, apart from the miners in the Nottingham area who didn’t join in the strike, the support on the ground for the miners was strong. The major newspapers including the so-called “left-wing” newspapers such as the UK Guardian joined with the right-wing tabloid rags (The Sun, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror) in opposing the action.

Some of the newspapers became propaganda machines for the Coal Board (for example, The Sun). The Coal Board later admitted that it had used the newspapers to publish false data about the number of strike breakers (particularly in Yorkshire) to undermine the morale of the striking workers. The newspapers continually published lies about the officials of the National Union of Miner (claiming corruption; pocketing strike funds for themselves etc).

Anyway, it was a grim time to be studying in the UK. The weather was bad enough but the general living conditions – the high unemployment, low wages, poor housing stock and poverty – in the North-West was to my eyes quite a challenge. I had grown up on a Post WW2 public housing estate, which in Australian terms was near rock-bottom. But our houses were like palaces compared to what the low-income workers had to live in around some of the tougher Manchester suburbs.

I thought about that time over the weekend when I was reading a report – – published last week (August 2, 2012) by the Manchester New Economy research organisation.

New Economy say that their:

… purpose is to create economic growth and prosperity for Manchester … home to a population of 2.6 million residents … [which] … generates 50% of the North West’s economic output and 5% of the total national economic output … [it is] … one of the six Association of Manchester Authorities (AGMA) commissions which were established in 2009.

It interacts with busines, universities and governments (all levels) to generate evidence-based cases for job creation and skills development; environmentally-sustainable investment opportunities and the like.

The Report was accompanied by a Press Release – The true cost of living in Manchester – which stirred a journalist at the (Manchester) Guardian newspaper to write this article (August 3, 2012) – £7.22 an hour – the price of a reasonable life in Manchester.

The Report provides a detailed analysis of the “changes to earnings and the cost of living in Manchester” and found that as at 2011:

Real wages and incomes of the lowest paid in Manchester have fallen dramatically since 2009, alongside substantial increases in the cost of essential goods and services. In real terms, hourly wages for the bottom 10% of earners in Manchester fell by 50p (7.5 percent) in two years. Real annual wages fell even more dramatically for the bottom 10%: part-time workers have faced a £619 (19.8 percent) wage cut and full-time workers’ pay fell by £904 (6.1 percent). There are an increasing number of households in Manchester that, even if they are able to secure full-time employment at the minimum wage, will earn less than they need to achieve a reasonable quality of life, even taking into account the benefits and tax credits to which they are entitled.

From which I concluded that the minimum wage in the UK is too low relative to what it costs to live. I hold the view that one should not work full-time at existing wages and be considered poor.

I also concluded that there were inadequate employment opportunities available in the Greater Manchester Region, a common problem in the UK generally.

I also concluded that the recession had impacted heavily on the least advantaged workers in that region and had introduced a deflationary dynamic – a second wave of malaise – which would ensure the private sector recovery would be slow and drawn out and if public spending support was denied then the economy would stay in recession with increased poverty for years to come.

The Report recommended, among other things that:

1. Policy-makers “should place greater weight on increasing the real incomes of those in low paid work”.

2. Action is needed “to raise the number of hours worked by the lowest paid”.

3. Skills development within a policy framework designed to expand the work opportunities.

4. Minimum wage should be a “living wage”.

I will come back to that Report later.

But then I read a Bloomberg Op Ed (August 6, 2012) – Mario Draghi Cannot Save the Euro – by former IMF Chief Economist Simon Johnson.

He argues that the ECB boss Mario Draghi has in recent weeks signalled through his public statements that “things are going to get ugly” in Euroland.

He asks the question:

… what, if anything, Draghi might achieve with a looser monetary policy. The euro area has many problems, including a lack of competitiveness in the periphery, chronically poor growth in countries such as Portugal and Italy, deeply damaged public finances in Greece and Spain, and a labor force that’s not mobile enough to go where the jobs are. Which of these could be resolved by reducing interest rates across the board?

I agree that the point he wants to focus on is a serious policy issue. The Eurozone is caught up in a dilemma of its own making. The nature of the monetary system is such that once a major asymmetrical negative aggregate demand shock hit it, there was no easy way out short of abandoning the whole show, which they should have done in 2008 or so.

The experiment failed. Now they are making things worse with consequences that will last for decades because of the political belligerence of those in charge.

I agree that monetary policy is not the correct instrument to be addressing the European crisis. I have noted many times that the prioritisation of monetary policy (and the eschewing of fiscal policy) reflects the ideological developments in my profession over the last three decades. The policy emphasis of the neo-liberals was to neuter the capacity of the treasury arm of government and to render the central banking arm devoid of political influence.

At the same time, the policy focus was to promote the “self-regulating market” via privatisation, deregulation and attacks on public welfare (to make workers more desperate and willing to accept the demeaning job offers that the deregulated labour market increasingly generated.

But I would not agree that the main issues now are structural rather than cyclical. The crisis hit in 2007-08 – it came very quickly despite the storm clouds being clear to all those who understood that the neo-liberal growth strategy (fiscal rules constraining net public spending and deregulation constraining real wages growth below productivity and promoting private debt growth) was unsustainable.

There were structural elements involved in this build-up – but I would locate those structural failures in the design of the monetary system rather than in the attitudes of workers or the lax behaviour of treasuries.

First, the deliberate strategy by Germany to attack their own workers’ rights by casualising segments of their labour market and stifling real wages growth (and thus constraining domestic demand growth) certainly allowed relative unit labour costs to decline in that nation by comparison with the other member states. But as a strategy for balanced growth across the region it was a disaster and has magnified the problems that the demand shock brought.

Second, without a floating exchange rate for each nation, trade imbalances that arose due to differential productivity had to increase the exposure of external deficit nations to the aggregate demand shock. The amount of work that fiscal policy had to do when the crisis hit was so much larger given the fixed exchange rates.

Third, with fiscal rules limiting the politically acceptable fiscal policy freedoms, it was obvious that the Eurozone nations would have to invoke harsh deflationary strategies which have only served to worsen the crisis and lock their nations into a vicious downward spiral of low growth/recession, shrinking tax bases and rising unemployment (given that it is an aggregate demand crisis overall).

Fourth, the common monetary policy allowed credit growth to exceed any rational limits in certain regions of Europe. Government played along with the myth that the self-regulating market would deliver sustained wealth to all.

Within that sort of system, the economies were certain to blow up if confronted with a serious cyclical decline in aggregate spending. The massive debt loads in the private sector (banks and households) and the collapse of the playing-card housing markets in certain nations exacerbated the regional effects.

I am currently studying the latest report from the EC on its Structural and Cohesion Funds program (see the Fifth Report) – as part of an investigation of how much redistribution has actually gone on in the EU under this scheme. Tracking down all the data is not straightforward and I will report my efforts some time soon (I hope). That should make some readers happier (Andrei!).

But what the accompanying Dataset to that Report shows is that despite massive disparity across the EU27 nations and their regions in real GDP growth, there was still positive growth – within the flawed structure of the system.

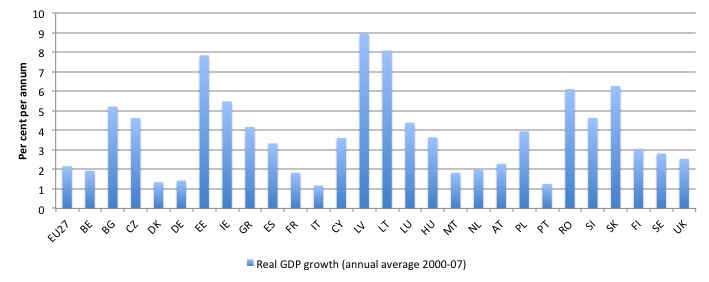

The following two graphs show the average annual real GDP growth from 2000-07 for the EU27 states and the EU27 overall (extreme left observation). The first graph shows the member-state level results. The second graph shows all the NUTS regions along with the national results to give you an idea of how much intra-national diversity there is on top of the obvious international diversity.

The horizontal axis in the second graph is a bit hard to read (given the number of regions) and the acronyms shown are the national EU signifiers. To the right of each of the national acronyms are the regions of that nation (so for example Estonia (EE) is clumped very close to Ireland because it has only two regions in the standardised geography).

But you can map the axis from the top graph to the bottom graph to get a better idea or download the data and have a look at the detail yourself.

The data shows that there was a huge diversity of growth outcomes across the EU27 regional space. Some of the economies that were growing strongly (for example, Ireland and the Baltic States, and to some extent Spain) were living in a fools’ paradise. The growth was never going to be sustainable – notwithstanding the financial crisis.

Their internal economies had become distorted by the growth of the construction and real estate sectors. Greece also grew strongly but that was on the back of strong public sector growth and tourism.

Other nations clearly struggled with chronically low growth (for example, France, Denmark, Italy, Portugal, and Germany (as it absorbed the low productivity Ost lands)).

I am studying the factors promoting a lack of convergence in the growth performance of these economies at present. The stated aim of the Structural and Cohesion Funds program is to promote convergence in economic performance. Divergence rather than the opposite characterised the early years of the Eurozone with the ECB replacing national central banks (so a common monetary policy across many EU states) and the same nations abandoning their currency sovereignty.

The question then is whether the growth that did occur despite all the “structural imbalances” was uniformly unsustainable. If other nations had not have expanded their external deficits then the German strategy would have led to recession earlier given it was stifling its domestic growth sources.

Certainly Spain, Ireland and the Baltic states would not have grown as fast in the absence of the real estate booms.

But despite these points, the main reason the Eurozone is in a massive crisis now is not because there are structural issues that need to be addressed. At the macroeoconomic level there is clearly a deficiency of total spending and for growth to occur that has to change.

It is clear that the private sectors are unwilling to drive the growth which means that export-led strategies will fail.

The UK Guardian economics editor Larry Elliot noted in his article over the weekend (August 5, 2012) – Three myths that sustain the economic crisis – that the crisis is being sustained by three myths:

The Anglo-Saxon myth is that big finance is a force for good, rather than rent-seeking and corrupt. The German myth is you can solve a problem of demand deficiency with belt tightening and export growth … [and] … a third myth – that there was not much wrong with the global economy in 2007.

He says that the global model in 2007 was deeply flawed “as it operated with high levels of debt, socially flawed in that the spoils of growth were captured by a small elite, and environmentally flawed in that all that mattered was ever-higher levels of growth”.

That has been one of my recurrent themes in my academic work (and my blog) for many years. The neo-liberal model of growth has failed. It is also not a way out of the mess.

It is clear that if the member states want to be part of a common monetary union and they want to minimise the degree to which there are federal transfers (of a macro not micro variety) then there cannot be massive cyclical demand asymmetries.

A nation state with its own currency can address asymmetries of this nature across its regional space directly. A Eurozone nation has limited capacity to do so within the stifled (and flawed) logic of the monetary system.

I make the distinction between macro and micro-motivated transfers within the system because the Structural and Cohesion Funds program are an example of the former and do not seek to address asymmetrical aggregate demand gaps that arise on a cyclical basis. A monetary union requires a macro capacity to quickly stimulate (or deflate) spending in regions (states) when these gaps (either demand-deficiencies or inflation-gaps) arises. The Structural and Cohesion Funds program are not designed to fill that purpose. I will explain all of that in a later blog once I have done some more research into the matter.

No-one is denying that structural issues are not important in Europe. I am not suggesting that real living standards in Greece can rise very much even with a fiscal-led growth expansion until they address productivity issues. The data shows that Greeks work long hours but have higher unit costs because their productivity is lower.

No-one is suggesting that if a nation surrenders its currency sovereignty then it better ensure it has a robust (growth-sensitive) tax base to allow public spending to service both structural and cyclical needs.

So how do we go back to the Manchester Report after all of this? Answer: via employment-rich fiscal policies.

The idea that governments just splash spending around the economy and hope for the best is flawed even though the major problem at present is a lack of spending. Most of the fiscal stimulus packages around the world were not employment-rich.

Massive amounts were spend (handed over) to the culpable banking sector to ensure their executives retained their capacity to rort the distributional system and maintain their salaries and bonuses.

A far better strategy would have been to introduce system-wide deposit guarantees and nationalise the failed private banks.

The Manchester Report tells me that minimum wages have to rise in that region but also, across the United Kingdom. The same policy would be usefully introduced in most nations.

But what about capacity to pay I hear you say? First, the evidence is that minimum wages do not undermine employment opportunities if aggregate demand is strong enough.

Of relevance to the UK, there was an interesting study from Stephen Machin entitled – Setting minimum wages in the UK: an example of evidence-based policy, which was presented to the Australian Fair Pay Commission’s swansong research forum in Melbourne in 2008.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at University College London, Director of the Centre for the Economics of Education and a Programme Director (of the Skills and Education research programme) at the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, an editor of the Economic Journal (one of the top academic journals), has been a visiting Professor at Harvard University and at MIT. So in mainstream terms he is thoroughly one of the orthodox club.

He examined the impact of the creation of the UK Low Pay Commission, which the Blair Labour Government established to try to remedy some of the worst excesses that the neo-liberal era had delivered to low wage workers. Both sides of politics in the UK from Thatcher onwards were remiss in this regard.

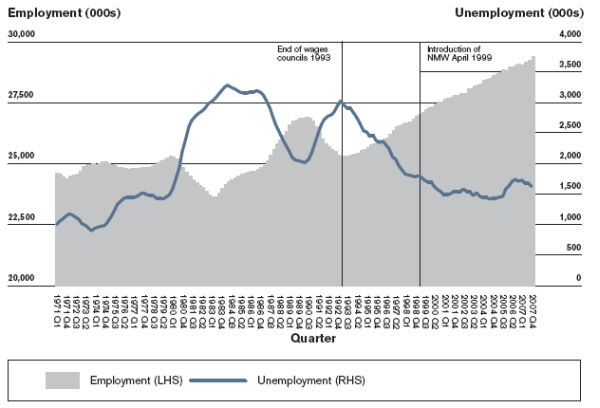

The UK Low Pay Commission (LPC) was established in 1997 and was given the task to define an effective National Minimum Wage (NMW). The following graph is taken from his Figure 1 (page 15) and is self explanatory.

Machin’s commentary is as follows:

The NMW was introduced in April 1999 at an hourly rate of £3.60 for those people over 21 years of age, with a development rate of £3.00 for those aged 18 to 21 years. The key economic question has been the impact of minimum wages on employment … Over the period 1999 to 2007, the macroeconomic picture indicates that employment continued to grow as minimum wages rose (Figure 1).

In terms of the effects on specific age cohorts, Machin concluded that:

Across all workers, there was no evidence of an adverse effect on employment resulting from the introduction of the NMW.

What about the effects in the most disadvantaged sectors? Machin reports on research that “searched for minimum wage effects in one of the sectors most vulnerable to employment losses induced by minimum wage introduction, the labour market for care assistants”.

He concluded that:

Even in this most vulnerable sector, it was hard to find employment losses due to the introduction of the minimum wage.

As I have noted previously, the 2006 OECD Employment Outlook entitled Boosting Jobs and Incomes, which was based on a comprehensive econometric analysis of employment outcomes across 20 OECD countries between 1983 and 2003 concluded that:

- There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

- The level of the minimum wage has no significant direct impact on unemployment; and

- Highly centralised wage bargaining significantly reduces unemployment.

The Australian Commission that sets minimum wages in Australia, Fair Work Australia, noted in its 2009-10 decision that:

Our attention was drawn to extensive literature and studies concerning the relationship between minimum wage rises and employment levels … The relevance of some of the studies is limited insofar as they are directed to the effects of increasing a single minimum wage in circumstances which are quite different to those which characterise the Australian industrial relations systems, including the range of minimum rates at various levels throughout the award system. Although a matter of continuing controversy, many academic studies found that increases in minimum wages have a negative relationship with employment, but there is no consensus about the strength of the relationship.

So one of the policies I would adopt to resolve the crisis in Europe and elsewhere would be to increase minimum wages to ensure that workers who engage in full-time employment are not below the relevant regional poverty line.

In this blog – Minimum wages 101 – I provide more discussion on the issue.

I noted that minimum wage setting should have nothing to do with cyclical stimulus policies. It has everything to do with how sophisticated you consider your nation to be. Minimum wages define the lowest standard of wage income that you want to tolerate. In any country it should be the lowest wage you consider acceptable for business to operate at. Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

If small businesses or any businesses for that matter consider they do not have the “capacity to pay” that wage, then a sophisticated society will say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in their economy. Firms would have to restructure by investment to raise their productivity levels sufficient to have the capacity to pay or disappear. The outcome is that the economy pushes productivity growth up and increases standards of living.

No worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable standard of living just because low wage-low productivity operator wants to produce in a country.

My recommendation that raising the minimum wage as a cure to the crisis is not inconsistent with that argument. In effect, what is lacking in the current climate is spending.

The lowest paid workers have less mortgage stress than others because they were unable to build up debt in the same way.

What they need is more spending power and there would be a significant surge in employment-generating demand should the mininum wage be raised in nations where it is clearly below acceptable (structural) levels.

I would also introduce a Job Guarantee immediately as a long-term commitment to stable employment but which would provide a significant short-run spending stimulus.

The Job Guarantee arithmetic is such that the rise in structural deficits that would be required to provide the extra minimum wage jobs would be relatively small – dwarfed by the bank bailouts that have gone before.

The ECB would be well advised to inform national governments that they will fund such schemes across the Eurozone. The cash would go to the most disadvantaged workers who would quickly transform it into spending.

The resulting stimulus to the private sector, knowing that this source of income would be stable, would boost private confidence and stimulate investment.

Public tax revenue would start to recover and the pressure from the bond markets would ease.

Please read my blog – Austerity proponents should adopt a Job Guarantee – for more discussion on this point.

For more information see the blogs that come up under this search string – Job Guarantee.

I will be talking about this in Brussels in September at the Employment Policy Conference the EC has organised. More specific details later.

Conclusion

I have run out of time today but the message is clear. The current approach to recovery in Europe and elsewhere is deeply flawed. It is based on the same ideological perspectives that created the problem. The solution cannot be found in these myths (as Larry Elliot calls them).

I also agree with Simon Johnson that long-run structural changes have to occur in some economies to give them a chance to sustain growth into the future. I would probably disagree as to which changes specifically should be made.

But all of that is moot when it comes to analysing what the current problem is – which I would argue is a lack of aggregate spending. We certainly do not want to go back to a situation where we drive private spending again by ever increasing levels of debt.

That is the current UK strategy and it will fail.

In acknowledging that the global economy in 2007 was flawed for the reasons Larry Elliot identifies we have to conclude that the neo-liberal approach to fiscal policy is also flawed. That is one of the tensions now. We cannot go back to private debt-driven growth but at the same time we cannot expect governments to run surpluses when the non-government sector is restoring balance sheet integrity.

But to help the most disadvantaged workers who are bearing the brunt of this crisis, immediate steps are possible – increase minimum wages and introduce guaranteed employment.

Then I would argue the demand deficiency would be well on the way to being solved and governments could turn their attention to the longer-term imbalances and structural constraints.

Introducing a viable socially liveable minimum wage and offering a worker a public sector job at that wage will neither break the budget nor undermine the capacity to engage in longer-term structural reform.

Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally

My Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally is now active.

I update it early in the day and again around lunchtime when all the sports are concluded for the day.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The potential problems with NMW is not the level itself but how fast it is increased. If in the UK NMW was increased by, say, 2% above inflation, genuinely viable companies who rely on low paid workers may not feel that sales will increase sufficiently to allow them to retain existing workers – thus there might be a trade-off between NMW increases against overall employment levels.

This could easily be solved by government introducing sufficient fiscal stimulus measures to reassure those companies that sales will increase to enable them to pay higher wages, all else being equal.

I don’t think that just because companies rely on low paid workers, that automatically means they should not be considered viable businesses, because it may simply be competition that is driving prices and wages ever lower, and not necessarily that these businesses need to exploit workers to be viable – hence fiscal stimulus would act to counter-balance these companies cash-flow expectations during large increases in NMW.

Kind Regards

Can’t believe Australia are one place ahead of the UK. I smell a rat.

You may be interested in the following article on low paid work in the UK and the decline in real wages which is being exacerbated by government policy.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/aug/06/squeezing-pay-prolong-uk-economic-pain

Another way (additional to fiscal stimulus) to ensure large increases in NMW do not cause under/unemployment to rise in response would be to allow companies to stagger the increase over successive quarters, thus this will reduce any “shocks” to their cash-flow.

“I don’t think that just because companies rely on low paid workers, that automatically means they should not be considered viable businesses,”

If they rely on low paid workers they are not viable, and they must increase their efficiency or their charges until they are, or cease to exist.

I don’t believe we should pander to business either. If you eliminate vast swathes of competition somebody will start to do well. That happens a lot when a large company lobbies for a ‘government initiative’ (such as training lots of people in a particular skill). Large company gets a reduction in their staff costs and all the little companies that were providing training or specialists skills disappear.

So change of government policy is a perfectly normal way of eliminating lots of businesses. You just don’t hear about it on the media.

Regarding:

“The Job Guarantee arithmetic is such that the rise in structural deficits that would be required to provide the extra minimum wage jobs would be relatively small – dwarfed by the bank bailouts that have gone before.”

Increasing the minimum wage is politically impossible in America right now. The more likely result of the next election will be mounting pressure to reduce or eliminate it. Proposing anything like the JG would land an American politician in an intense firestorm of hate-speach which our media, far from intervening to moderate, would only revel in putting on display. So, good luck in Brussels, Bill. Maybe some shred of civility and civilized behavior toward the weak persists there.

My question is why the JG would raise “structural deficits”, a term I poorly understand and don’t often encounter on MMT sites – except when excessive concern about them is being denounced as neoliberal BS and a lame excuse for doing nothing. Anyway, if the JG ends the recession, restores full employment, ignites growth, and ultimately puts most of itself out of business, all of which we believe it will do, where do “structural” (doesn’t this mean “permanent”?) deficits come from? I don’t get it.

Cheers

At some point the 800 pound gorilla in the room needs attention. It is the tollbooth between labor wages and purchasing power set up by unearned income. Labor is the only source of surplus creation, everything else is a transfer or theft, legal or illegal. The negative effect of Capital’s unearned income tax on labor is growing. It has already stalled growth. It is the reason behind the Keynsian Equilibrium theory of unemployment. The tollbooth excludes the unemployed from economic participation, any spare change is drained immediately.

For example, interest is the theft of a man’s future spending power, borrow twenty and pay back eighty. This will be the one lesson the students remember each payday for years to come.

Bill,

Needless to say the attack onworking conditions and wages continues apace especially in the regions. The next line of attack is regional pay bargaining as opposed to national wage bargaining. This would of course remove the one remaining stimulus to aggregate demand in already depressed regions.

This will simply perpetuate the inbuilt lack of ability to compete with London and the South East. The neo liberal reply is that private employers will immediately step in to take on the cheap workers….

Except we all know they won’t.

Neil Wilson,

Thanks for the reply:

“If they rely on low paid workers they are not viable, and they must increase their efficiency or their charges until they are, or cease to exist.”

I think the point I was trying to make was this:

Many companies pay very low wages because their competitors do the same thing, that way in a fiercely competitative sector, prices are driven down by driving down wages. If all companies within that sector were forced to pay more through government raising the minimum wage, these companies would still be able to profit and therefore be viable.

I agree that if a company is forced to increase its wages, and that in turn forces it out of business, then that company is not viable.

I was actually thinking of SMEs when I made my point. Given in the UK SMEs (not corporates) find it hard to get credit when they have temporary cash-flow problems, and this may result in employees working shorter hours etc unnecessarily in response to the initial shock of paying a much higher minimum wage.

Government can ease this with some fiscal stimulus, and implementing the change incrementally over the year perhaps.

Kind Regards

Bill –

What is your source for this extraordinary claim? All the reports I’ve seen, including the Wikipedia page you linked to, show it to be in response to the Thatcher Government’s attempt to close down economically unviable coal mines.

Why complicate the problem or the solution?

The Problem: A government backed/enforced credit cartel drove the population into onerous debt. It simultaneously cheated non-debtors via negative real interest rates.

The Solution: Bailout the entire population equally with new fiat till ALL credit debt is paid off. The new fiat will also be the basis for honest, 100% reserve lending.

As for jobs, the above plus legitimate but generous infrastructure spending and the revived economy resulting therefrom should provide those. And if not, then per Michael Kalecki:

“Nor should the resulting fuller utilization of resources be applied to unwanted public investment merely in order to provide work. The government spending programme should be devoted to public investment only to the extent to which such investment is actually needed. The rest of government spending necessary to maintain full employment should be used to subsidize consumption (through family allowances, old-age pensions, reduction in indirect taxation, and subsidizing necessities).” Michael Kalecki from http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/08/kalecki-on-the-political-obstacles-to-achieving-full-employment.html [emphasis added]

“All the reports I’ve seen, including the Wikipedia page you linked to, show it to be in response to the Thatcher Government’s attempt to close down economically unviable coal mines.”

Without replacing the work with anything else – destroying those communities unnecessarily.

The ‘magic’ of the private sector hasn’t replaced the work. The coal redevelopment money has been used to build roads to nowhere and employment light warehouses. Markham Vale redevelopment might boast 100,000 sq ft let in 20 weeks on their advertisement hoardings, but they don’t mention how many jobs that equates to in an automated warehoure, nor how many net jobs they are short from when the pit was there. And that was one of the Derbyshire mines.

Turn right rather than left into the estate of overpriced three storey rabbit hutches they’ve built on Woolley Colliery pit head and you’ll find yourself in a row of terraced miners cottages occupied by those on now benefits. The despair hangs in the air like a cloud. Having expensive housing across the road is just putting the boot in.

You might want to graduate from reading Wikipedia pages written by the victors and come and look at some real people for a change.

The ideology didn’t deliver: time to replace it with a system that works.

Take a visit to Newtongrange mining museum. Unlike many industrial heritage entertainments, it does a very good job of showing how shit being a miner was for most of its history, and how it only became bearable for a few short years before its execution.

It was an object lesson in how ruthlessly austrians reach for the power of the state when it suits their own ends.

I’m sure a few pensioners/low paid/unemployed looking at their gas bills this winter will wonder if we should have disposed of a strategic energy resource on a ideological whim.

Dear Aidan (2012/08/07 at 2:35)

I was living just around the corner at the time from the Warrington plant where Eddie Shah produced the Stockport Messenger. I presume you know the history of that incident which began the Thatcher government attack on the Triple Alliance. The mining strike was part of that scenario.

There was no question that the Yorkshire mines were inefficient when compared to say the Nottinghamshire mines which had the latest equipment. But the attack on the miners was a coordinated and planned attack on the three big unions to cut their power and capacity to oppose anti-worker legislation (of which a lot followed).

best wishes

bill

I was living in the UK at the time of the miners’s strike. Bill’s claim that the Thatcher v. Scargill show down was a “a coordinated and planned attack on the three big unions to cut their power and capacity to oppose anti-worker legislation” is news to me.

My impression was that Thatcher’s main motivation was her free market beliefs: e.g. that unviable businesses should be closed down, regardless of whether they were coal mines or anything else. She also opposed monopolies of any sort, and that included trade unions and middle class so called “professional associations” (i.e. trade unions). She had a go at both.

Some of the coal mines were uneconomic to a TOTALLY LUDICROUS degree: they didn’t just make a loss. The losses were so large that sales apart from not covering wages, did not cover all the cost of materials consumed by the relevant mines. I.e. output was actually NEGATIVE. Or put another way, the country would have gained an immediate economic benefit from paying the relevant miners to stay at home on full pay and do nothing.

“She [Thatcher] also opposed monopolies of any sort, …” Ralph Musgrave

But not the banking cartel? The banking cartel is somehow always a given. The rest of us must compete fiercely to earn what the bankers make, money.

You can raise the minimum wage in nominal terms but not in real terms, which is what matters.

Imagine you wish to improve the lot of Walmart workers making $10/hr. You decree they should make $20/hr. In fairness, you should also increase the wages for McDonald’s workers to the same wage level and the same for all low-skilled workers in society. When they go to purchase goods and services from each other, they will find that their money goes no further than it did before as the higher wages are passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices. Also, you will develop a shortage of skilled labor as there will be a decrease in the incentive for higher education. That will drive up the cost of skilled labor until the market balances at a higher wage level. In the end, you will have a society with higher prices and higher wages but the same ratio for wages between low-skilled labor and high-skilled labor will still exist. Nothing will have changed.

You can raise the minimum wage in nominal terms but not in real terms, which is what matters. Ahmed Fares

But debt is measured in nominal, not real terms, so at least the debtors would be helped.

Yes, F. Beard, even the banking cartel – hence financial deregulation.

hence financial deregulation. Aidan

But without abolishing deposit insurance, a lender of last resort, and borrowing by the monetary sovereign!

Bill,

Have you ever thought of making a documentary ? The content in this article alone would send a very powerful message, and perhaps get some more people behind MMT.

The sooner the masses understand that unemployment is an arrangement between governments and the plutocrats – the better.

“genuinely viable companies who rely on low paid workers ”

If you cannot pay a living wage then your business is not viable.

Bill –

The problem wasn’t that they weren’t the most efficient, it’s that they were running at a loss. They wewre relying on government subsidies, and it was a waste of resurces that could be put to better use elsewhere.

And considering how they’d used that power, it was something that needed doing. They were protecting inefficient working practices, and strikes were inconveniencing everyone else.

Unfortunately there were many in the government who, like you, failed to see the difference between anti worker legislation and curbing union power to disrupt. I remember seeing on Lateline in the ’90s a British former cabinet minister commenting that Australia’s new industrial relations laws were still way behind those of Britain (completely oblivious to the much better results that Australia was already getting). Alas the problem was never solved, and Britain is still plagued by dinosaur unions.

Neil Wilson –

Automated warehouses are good for the manufacuturing industry, but that’s something that governments have been neglecting ever since.

Where are the roads to nowhere?

If lots of expensive houses have subsequently been built in the area, that suggests that there are plenty of jobs – or at least were before the GFC.

Ahmed, if Walmart workers were making $10/hr, you would already have succeeded in improving their lot. $10/hr is in approximately the US Federal minimum wage of 1968 in terms of real purchasing power. In real terms, the current US Federal minimum wage is over 20% below the $10/hr level of 1968 (in 2010$). And the answer to the thought experiment that “there is some minimum wage increase which is too much, too fast to be accommodated without much of the increase being lost to inflation” is, then don’t do it that much, that fast. It would be absurd to claim that any increase in the minimum wage would be entirely lost to inflation in a nation, like the US or UK, with a substantially depressed labor market and production well beneath productive capacity. That is the old monetarist “more money chasing the same amount of goods” argument, and obviously in the current US or UK economic conditions, there is ample capacity to produce more goods in response to customers finding themselves with more money in their pocket.

It would be absurd to claim that any increase in the minimum wage would be entirely lost to inflation in a nation, like the US or UK, with a substantially depressed labor market and production well beneath productive capacity. BruceMcF

Bear in mind that inflation comes in two variants: cost-push and demand-pull. The example I gave of Walmart workers causing price increases would be a case of cost-push inflation. Even in recession, these costs are passed along.

And yet increases to executive salaries are never inflationary.

“If lots of expensive houses have subsequently been built in the area, that suggests that there are plenty of jobs – or at least were before the GFC”

It suggests that there was plenty of debt available, poor building regulations, lousy housing policy and a bubble in land prices with planning permission. Why else would you build houses on an old pit head with a glorious vista of the M1 motorway, slag heaps and broken down terraces?

The next village along is Woolley which is where Yorkshire millionaires live. There is a reason the estate is called Woolley Grange, not Darton Grange.

And it ain’t anything to do with providing decent housing for ordinary people to bring up their families.

“My impression was that Thatcher’s main motivation was her free market beliefs:”

I doubt that. The main motivation I feel was not to fall victim to a miner’s strike like her predecessor.

The state had evolved their tactics. The miners tactics hadn’t and they were led by a firebrand idiot who wasn’t really interested in miner welfare or the future of the mining industry in the UK.

The main motivation was the destruction of union power, and it was outlined clearly in the 1974 Ridley plan. Scargill’s tactics were all wrong, and his motivations too widely spread, but his prognosis was spot on. Against a determined, well organised and powerful antagonis, the choice was to fight and lose or lose without a fight.

Increase the wages of the poor and raize their purchasing power. Also increase the taxes of the rich and lower their employment benefits eg. Loans & Allowances.

Neil Wilson –

Wooley Grange isn’t far from Darton station, so before the GFC there wouldn’ve been much difficulty getting to where the jobs were.

“Wooley Grange isn’t far from Darton station, so before the GFC there wouldn’ve been much difficulty getting to where the jobs were.”

I doubt the white Audi owners on the estate would lower themselves to using the train.

I always wonder what would have happened to billy elliot if he had wanted to be a miner.

Ahmed Fares: \”You can raise the minimum wage in nominal terms but not in real terms, which is what matters.

\”Imagine you wish to improve the lot of Walmart workers making $10/hr. You decree they should make $20/hr. In fairness, you should also increase the wages for McDonald’s workers to the same wage level and the same for all low-skilled workers in society. When they go to purchase goods and services from each other, they will find that their money goes no further than it did before as the higher wages are passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices.\”

For one thing, you are ignoring the effect of wage increases upon creditors and rentiers. For another, while raising the minimum wage will raise other wages, those raises will not be proportional. For another, to the extent that profits are rents, there is room for them to be reduced. All in all, resultant price increase is unlikely to equal the one time increase in the minimum wage.

Ahmed, since low wage labor is far from 100% of Walmart’s costs, then even if 100% of the increase in wage costs on low wage labor are passed along, the percentage price increase will be substantially less than the percentage increase in the wage to the workers, so the cost-push inflation cannot, arithmetically, eliminate the real income increase. Given that in the US, the bottom quintile of wage earners earn under 4% of income, and the bottom two quintiles earn less than 15% of incomes, the suggestion that cost push inflation from an increase in minimum wages can entirely eliminate the increase in real terms is silly.

.

From simple arithmetic and knowledge of income shares, the argument that cost-push inflation from increases in labor costs will eliminate the real increase in income resulting from any an increase in the minimum wage, no matter how modest, is laughable.

.

The notion that Walmart prices would increase by a percentage amount equal to the percentage increase in the wage earned by a portion of their workforce, when those wages represent (1) a proper fraction of their margin on goods sold, which itself is (2) a proper fraction of their retail prices is particularly amusing.

.

A red flag that you were not engaged in serious analysis on a substantial empirical foundation was given by the fact that your hypothetical was to raise the minimum wage from something close to a US living wage, and well over the actual minimum wage, to a wage rate well over the US median wage.

BruceMcF,

I see that I’ve amused you. Let me amuse you some more.

If I buy a toaster at Walmart, part of the price is labor and part is the wholesale cost to Walmart of the toaster. But the toaster contains the embedded cost of other workers’ labor. From the people who produce the raw materials to the people who assemble it. Some of this labor is high-skilled and some is low-skilled. In my example, I stated that all low-skilled labor would be entitled to the same wage increase and high-skilled labor would adjust upwards for the reasons I gave, so that the wage ratio between high-skilled labor and low-skilled labor would remain the same.

So, contrary to what you’ve stated, Walmart’s costs are completely 100% labor. Where you see a toaster, I see the labor used in the production of that toaster. The wholesale cost of the toaster would rise and Walmart would pass that cost along also. So I stand by my contention. The same percentage increase in prices will follow the same percentage increase in wages.

paul – he’d probaby have emigrated to Australia!

Ahmed Fares, it’s not 100% labour. Some of the cost is due to taxation other than taxes on labour. Some is The cost of leasing land. Some is financing cost. And some is profit returned to shareholders.

Just because high skilled labour costs would adjust upwards doesn’t mean the ratio would remain constant. And governments can do a lot to encourage more people into higher education even if the wage outcome bebefits are reduced.

Whether increasing the minimum wage would be a good idea is disputable, and I would say it isn’t in the current economic circumstances. But it certainly can be raised in real terms.