I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

Minimum wages 101

The issue of minimum wage adjustments always invokes a lot of debate and invokes the usual (boring) reactions from employer groups and conservative economists. Their narrative is always the same: you cannot have a minimum wage rise because it will cause unemployment among the low-skill ranks of the workforce. If you believed their logic, then there never would be a minimum wage rise. The reality is that there is no evidence available to support these notions and lots of evidence to refute it. The new problem is that the current Federal government is now aligning with the conservatives and using the same defective logic to oppose any reasonable rise in the minimum wage. Its that time again. Time to debrief.

The ACTU Submission to the Australian Fair Pay Commission (AFPC) makes the case for a wage rise of $21 per week which they consider will preserve the real value of the Federal minimum wage (FMW). They are assuming an inflation rate of around 3.8 per cent between October 1, 2008 and October 1, 2009. The AFPC made its last decision active on October 1, 2008 and so it is expected that the next adjustment in the FMW will be on the same day in 2009.

A $21 rise would take the FMW from $543.78 a week to $564.78 a week. The impact on overall aveage earnings would be fairly small given that only a small fraction of the workforce rely on the (pitifully low) FMW. Is $21 per week required to preserve the real FMW? Clearly this depends on how you measure inflation and what you project the inflation rate to be. Later in this blog I provide some projections.

The current Federal government has indicated that they oppose the ACTU’s submission as it is “excessively large” and will generate “job losses and burden small businesses”. What? Don’t they ever look at the research literature? Didn’t they claim they were going to be the “evidence-based” government? Haven’t they actually read previous Australian Industrial Relations Commission decisions?

If you are interested in some previous evidence go to HERE and HERE and search for Professor Mitchell. Also search for Lewis and Watson. It is also interesting to read the whole transcript of the decisions. Whatever, the balance of evidence clearly negates the neo-liberal logic. Nothing has changed since!

Rather surprisingly, the Chair of the AFPC, Ian Harper gave an interview to the Australian Financial Review recently and admitted that he believed there is a negative relationship between employment and minimum wages. So he has already decided? Where is the impartiality in the review process?

And it seems the Federal government has fallen into the mire of confused logic by supporting Harper’s comments and indicating that employment will fall if minimum wages were increased significantly (say at a rate to preserve real values) because of the slowing economy.

But the loss of employment in a slowing economy is because there is nothing for them to do. It is a demand problem not a cost problem. If there is nothing for the workers to do it doesn’t matter how low wages are. Firms will not hire if they cannot sell the goods and services that the workers produce. Firms do not want to accumulate inventories. The only way that real wage cuts would increase employment would be if in some way they stimulated a fall in the private desire for saving (that is, boost private spending). There is no evidence that this would ever happen. In other words, this method of stimulating employment will always fail at the macroeconomic level.

The Federal government can do something about employment losses when the macroeconomy is suffering from constrained spending, as it is at present. It can use its fiscal sovereignty to directly create public sector employment for low-skill workers and prevent the impacts of the recession undermining their employment prospects.

It is true that the Government can protect low-skill workers with so-called “social wage” measures (for example, by targetted tax cuts) and employers are always keen for the costs of their businesses to be socialised into public spending (or revenue foregone). There are times when it is appropriate for the social wage to be socialised but there is very little justification at the minimum wage level for business costs to be subsidised by the public purse.

Real wage maintenance creates permanent losses for workers

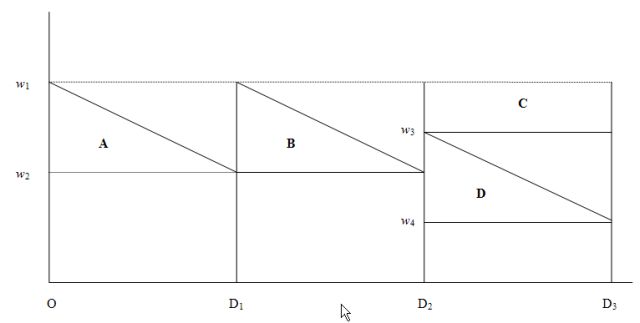

There are also problems with just “maintaining real FMWs” if there are long gaps between adjustments. With inflation going on continuously (more or less), the annual adjustments by the AFPC hand employers huge gains and deprive the workers of real income. The following discussion and diagram explain why.

Assume that at the time of policy implementation, the real FMW wage was wi and there was no inflation. The wage setting authority (in this case the AFPC) manipulates a nominal minimum wage (the $ weekly value) and the real wage equivalent of this nominal wage is found by dividing the nominal wage by the inflation rate. Assume that inflation assumes a positive constant rate at Point 0 onwards.

The nominal wage is the $-value of your weekly wage whereas the real wage equivalent is the quantity of real goods and services that you can purchase with that nominal wage. For a given nominal wage, if prices rise then the real wage equivalent falls because goods and services are becoming more expensive.

The following diagram depicts the real income losses that arise when indexation is not continuous, that is, when the AFPC makes, say, an annual adjustment in the FMW (you may want to click it to get it in a new window so you can print it while you follow the description):

Over the period O-D1 the inflation rate continuously erodes the real value of the nominal wage and immediately before the next indexation decision, the real wage equivalent of the fixed nominal FMW is w2. The real income loss is computed as the area A, which is half the distance (0-D1) times distance (w1-w2).

At point D1 the wage setting authority increases the nominal wage to match the current inflation rate which restores the real wage to w1, but the workers do not recoup the deadweight real income losses equivalent to area A.

The same process occurs in the period between the D1 and the next decision D2, resulting in further real income losses equivalent to area B. These losses are cumulative and are greater: (a) the higher is the inflation rate; (b) the longer is the period between decisions; and (c) the higher is the real interest rate (reflecting the opportunity cost over time).

Clearly, the patterns of real income loss are different if the wage setting authority adopts a decision rule other than full indexation (that is, real wage maintenance). For example, say it decides not to adjust nominal wages fully at the time of its decision (or in fact at the implementation date of its decision) to the current inflation rate then the real income losses increase, other things equal.

So at time D1 the authority decides to discount the real wage (less than full indexation) and increases the nominal wage rate such that the real wage at that point is equal to w3.

Over the next period to D3, the real wage falls to w4 and at the time of the next decision (implementation time D3) the real income losses would be equal to the triangle D (reflecting the inflation effect over the period D2- D3, plus the rectangle C, which reflects the losses arising from the decision to partially index at D2.

Similarly, one can imagine that the adjustment at a particular time might involve a real wage increase (more than full compensation for the current inflation rate) which would then partially offset some of the real income loss borne in the previous period when nominal wages were unadjusted but inflation was positive.

So if you understand the saw tooth pattern of indexation shown here you will see that the triangles A and B represent real losses for the workers between wage setting points even if real wage maintenance is the preferred policy. These losses are worse (areas C and D) if there is only partial adjustment. These losses occur because inflation is a more continuous process than the adjustments in FMW and accrue to the employer. The employers are pocketing these wage losses every day because their revenue is geared to the price rises and they are paying constant nominal wages to the workers.

No strong neo-liberal evidence

Many academic studies have sought to establish the empirical veracity of the neoclassical relationship between unemployment and real wages and to evaluate the effectiveness of active labour market program spending. This has been a particularly European and English obsession. There has been a bevy of research material coming out of the OECD itself, the European Central Bank, various national agencies such as the Centraal Planning Bureau in the Netherlands, in addition to academic studies. The overwhelming conclusion to be drawn from this literature is that there is no conclusion. These various econometric studies, which have constructed their analyses in ways that are most favourable to finding the null that the orthodox line of reasoning (that wage rises destroy jobs) is valid, provide no consensus view as Baker et al (2004) show convincingly.

In the last 10 years, partly in response to the reality that active labour market policies have not solved unemployment and have instead created problems of poverty and urban inequality, some notable shifts in perspectives are evident among those who had wholly supported (and motivated) the orthodox approach which was exemplified in the 1994 OECD Jobs Study.

In the face of the mounting criticism and empirical argument, the OECD began to back away from its hardline Jobs Study position. In the 2004 Employment Outlook, OECD (2004: 81, 165) admitted that “the evidence of the role played by employment protection legislation on aggregate employment and unemployment remains mixed” and that the evidence supporting their Jobs Study view that high real wages cause unemployment “is somewhat fragile.”

The winds of change strengthened in the recent OECD Employment Outlook entitled Boosting Jobs and Incomes, which is based on a comprehensive econometric analysis of employment outcomes across 20 OECD countries between 1983 and 2003. The sample includes those who have adopted the Jobs Study as a policy template and those who have resisted labour market deregulation. The report provides an assessment of the Jobs Study strategy to date and reveals significant shifts in the OECD position. OECD (2006) finds that:

- There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

- The level of the minimum wage has no significant direct impact on unemployment; and

- Highly centralised wage bargaining significantly reduces unemployment.

This latest statement from the OECD confounds those who have relied on its previous work including the Jobs Study, to push through harsh labour market reforms (such as the widespread deregulation in Australia as a consequence of the WorkChoices legislation), retrenched welfare entitlements and attacked the power bases on trade unions. It makes a mockery of the arguments that minimum wage increases will undermine the employment prospects of the least skilled workers.

OECD (2006) finds that unfair dismissal laws and related employment protection do not impact on the level of unemployment, merely the distribution. In my own work (references are available on request) I have consistently pointed this point out. In a job-rationed economy, supply-side characteristics will always serve to only shuffle the queue.

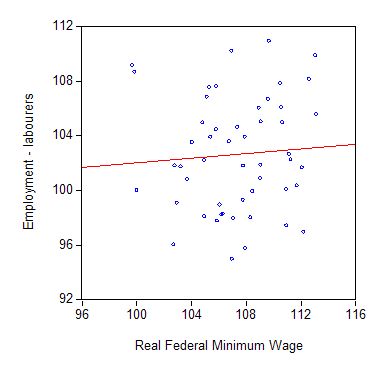

To get some idea of what the data looks like I created a scatter plot of the real federal minimum wage (indexed to 100 at September 1996) (horizontal axis) and the Employment of labourers (vertical axis). The red line is a simple regression which looks pretty flat to me (indicating no relationship). If there is any relationship it is positive which means the higher the minimum wage index the higher is the labourers’ employment index. But when you run the regression in change form (don’t worry about what this means if you don’t know) one concludes there is no relationship.

What should the FMW be in October 2009?

The answer to that question depends on what your goals are. But to keep it simple, lets just see what would be the new FMW which would preserve the real value of the FMW measured at October 1, 2009 compared to October 1, 2008 (the last time the FMW was adjusted upwards). Don’t forget though that those loss triangles are still accruing as daily benefits (similar to real wage cuts) to the employers.

The CPI is currently not available for the first quarter 2009. To make the projection tractable I offer various assumptions about the course on inflation over 2009 and adjust the FMW upwards as appropriate. The following table shows the adjustment applicable on October 1, 2009 for an annual inflation rate of 2.0 per cent, 2.5 per cent, 3 per cent, and 3.5 per cent. I have compounded the inflation rate adjustment daily over the year.

According to the ABS, the current inflation rate is 3.6 per cent for All Groups and 2.4 per cent for All groups excluding Housing and Financial and insurance services. I expect inflation to be around 3 per cent per annum over the period between October 2008 and October 2009 with an upside risk given recent signals from oil markets. So something between 3 and 3.5 per cent over the year between adjustments is plausible.

If these assumptions are accurate then an FMW adjustment upwards in the high teens is reasonable to maintain the real FMW. There is absolutely no justification for cutting the real equivalent which would be the case if something lower than this was decided by the AFPC.

| Inflation rate assumption (% per annum) | ||||

| 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | |

| New FMW ($ per week) | $554.76 | $557.55 | $560.34 | $563.15 |

| $ change per week | 10.98 | 13.77 | 16.56 | 19.40 |

Conclusion

In my view, minimum wage setting has nothing to do with cyclical stimulus policies. It has everything to do with how sophisticated you consider your nation to be. Minimum wages define the lowest standard of wage income that you want to tolerate. In any country it should be the lowest wage you consider acceptable for business to operate at. Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

If small businesses or any businesses for that matter consider they do not have the “capacity to pay” that wage, then a sophisticated society will say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in their economy. Firms would have to restructure by investment to raise their productivity levels sufficient to have the capacity to pay or disappear. The outcome is that the economy pushes productivity growth up and increases standards of living.

No worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable standard of living just because low wage-low productivity operator wants to produce in a country.

The statements by the AIG and other employer groups should be dismissed as self-seeking assertion. The position of the Government is another matter and I would have hoped they took a more progressive position in relation to our most disadvantaged (employed) workers. Whatever happened to their social inclusion agenda?

Digression – Filipino workers:

I am currently still in Manila working for the Asian Development Bank on projects in Central Asia (job creation, regional development, skills development, macroeconomic risk assessment). I will report on this work when contractual arrangements allow.

But in the Philippine Star newspaper yesterday, I read that the Philippines senate (government) is currently debating whether they will introduce an unemployment benefit as part of their social security system given the negative impacts of the financial crisis on employment here. The situation for Filipino families is also heavily dependent on foreign workers – a staggering 25 per cent of the workforce work abroad and remit their salaries back to their families given wages are so low here. These workers are spread around the World and are now facing unemployment themselves.

The government appears to be opposing the proposal, with the Senate President saying “… once the program is in place, government will be hard put in dismantling it.” He also asked “where the government would get the funds to provide those who were jobless …” This is notwithstanding the reality that the Philippines Government is sovereign in its own currency and could easily pay the benefits to their workers.

So things are pretty bleak for workers here with unemployment rates currently around 11.2 per cent and rising, with 14 per cent unemployment in central Manila. Underemployment is very high at the best of times.

Digression – Saturday quiz:

Coming tomorrow evening Australian EST.

Bill the links HERE and HERE come up with;

The specified result list contains no documents