I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The CON merchants who buttress the neo-liberal ideology

Two things led to this blog today. First, the IMF has once again been lecturing the world on economic policy. In the Global Financial Stability Report and the World Economic Outlook Update – both released yesterday (July 16, 2012) the IMF has downgraded their growth forecasts again yet is hanging on to the myth that austerity is the path to resolution and that the deficit reductions underway are appropriately growth supporting. Doesn’t anyone in the IMF understand logic? One cannot on the one hand admit that growth is falling below previous forecasts yet on the other hand claim that policy which caused growth to slump is growth supporting. Second, Anna Schwartz died in New York on June 21, 2012. The two events can be linked.

The EUObserver article (July 16, 2012) – IMF tells eurozone to turn on printing presses – is representative of the press reaction to the latest IMF reports, which show how compromised the IMF has become. I might consider the latest IMF World Economic Outlook tomorrow in more detail. But the motivation today is the continued belief that monetary policy matters.

They quote the IMF as saying in the WEO:

There is room for monetary policy in the euro area to ease further. In addition, the ECB should ensure that its monetary support is transmitted effectively across the region and should continue to provide ample liquidity support to banks under sufficiently lenient conditions … The utmost priority is to resolve the crisis in the euro area …

At the outset of the crisis in early 2008 the major policy reaction was to prompt central banks to drop interest rates and then engage in quantitative easing and other so-called non-standard monetary policy initiatives (swaps arrangements etc.)

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

The fiscal policy responses came a bit later and clearly were reluctant innovations.

This prioritising of monetary policy stems from the Monetarist era (1970s and onward) where the profession abandoned the dominant Keynesian macroeconomic paradigm in favour of

In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we cover this paradigm shift in some detail. Specifically we show that Milton Friedman’s work unambiguously aimed to build on the early research of Irving Fisher and was up against a new macroeconomic orthodoxy in the 1950 – Keynesian thinking.

By the 1920s, Irving Fisher was setting the groundwork for what became Monetarism some 42 years later. The work of Fisher was obscured by the rise of Keynesian macroeconomic orthodoxy.

Friedman and others were working on the foundations of a resurgence of Neoclassical macroeconomics based on the Quantity Theory of Money during the 1950s and 1960s. The Monetarist reinterpretation of the trade-off between unemployment and inflation, which emphasised the role of expectations, revived the Classical (pre-Keynesian) notion of a natural unemployment rate (defined as equivalent to full employment). The devastating consequence was the rejection of a role for demand management policies to limit unemployment to its frictional component.

They recast the Phillips curve (the relationship between inflation and unemployment) to be a relationship where mistakes in price expectations drove real shocks (via supply shifts) rather than the way the Keynesians constructed the relationship – real imbalances (excess labour supply – that is, unemployment) driving the inflation process (via demand shocks).

The two approaches are not the slightest bit similar and constitute two separate paradigms (or philosophical enquiries) although one cannot cast it as a Kuhnian shift (see below).

The importance of this shift in macroeconomic thinking after the OPEC oil shocks to Monetarism was that it scorned aggregate demand intervention to maintain low unemployment. Any unemployment rate was optimal and the a reflection of voluntary, utility-maximising choices. The policy emphasis shift from full employment to full employability and the period of active labour market programs began in earnest.

The rise in acceptance of Monetarism and its New Classical counterpart was not based on an empirical rejection of the Keynesian orthodoxy, but in Alan Blinder’s words:

… was instead a triumph of a priori theorising over empiricism, of intellectual aesthetics over observation and, in some measure, of conservative ideology over liberalism. It was not, in a word, a Kuhnian scientific revolution.

The stagflation (coincidence of inflation and unemployment) in the 1970s (the so-called shift in the Phillips curve) associated with the OPEC ructions led to a view that the OECD economies were failing and provided a strong empirical endorsement for the Natural Rate Hypothesis, despite the fact that the instability came from the supply side.

Any Keynesian remedies proposed to reduce unemployment were met with derision from the bulk of the profession who had embraced the new theory and its policy implications. The natural rate hypothesis now became the basis for defining full employment, which then evolved to the concept of the NAIRU.

Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

The inflation was interpreted by Monetarists to be a vindication of the classical Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), which draws a relationship between the growth in the money supply and the rate of inflation.

The QTM is written in symbols as MV = PQ. This means that the money stock (M) times the velocity of money – the turnover of the money stock per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and claim that Q is always at full employment as a result of free market adjustments.

So this theory denies the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

So by claiming that V and Q are fixed, it becomes obvious that changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

Given that the central bank was deemed responsible for the growth of the money supply the conclusion was simple.

Governments (central banks) were to blame for inflation because they were too busy “printing money” to try to keep unemployment low (lower than the supposed but mythical NAIRU) and that they should adopt a monetary targetting rule to provide certainty.

Please read my blog – Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on this point.

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will respond by increasing real output to maintain market share.

Moreover, as I explain in this blog – Money multiplier and other myths and these blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – the central bank cannot control the money supply anyway.

Which brings me to the death of Anna Schwartz. The New York Times ran an obituary on the day of her death (June 21, 2012) – Anna Schwartz, Economist Who Collaborated With Friedman, Dies at 96.

It said that she was “a research economist who wrote monumental works on American financial history in collaboration with the Nobel laureate Milton Friedman while remaining largely in his shadow …”

It said that she was referred to as the:

“high priestess of monetarism,” upholding a school of thought that maintains that the size and turnover of the money supply largely determines the pace of inflation and economic activity.

So the QTM.

The NYT says that:

The Friedman-Schwartz collaboration “A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960,” a book of nearly 900 pages published in 1963, is considered a classic. Ben S. Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman, called it “the leading and most persuasive explanation of the worst economic disaster in American history.”

The authors concluded that policy failures by the Fed, which largely controls the money supply, were one of the root causes of the Depression.

So you can see that current monetary policy is probably still being influenced by this work and certainly a substantial component of the hyperinflation scaremongering is influenced by the work.

I have taught and used in my research advanced time series econometric techniques for more than 25 years now and was part of the David Hendry revolution as a graduate student in the early 1980s This approach – known as the general-to-specific approach – demonstrated that much of the time series work prior to the late 1970s was invalid and should be discregarded.

The roots of this new approach to econometric modelling emerged out of discontent in the 1970s with the state of art.

Scepticism was growing in the 1970s that the traditional – specific-to-general – techniques were delivering useless results. For example, LSE econometrician Meghnad Desai wrote in his 1976 Applied Econometrics book (page vii) that:

Even within the academic profession, one is sensing a doubt as to whether the generation of more numbers for their own sake is fruitful. The ad hoc approach of many practising econometricians to the problem of hypothesis testing and inference is illustrated by the popular image of much econometrics as a high R2 in search of theory. Garbage in-garbage out is ow many describe their own activity.

For the non-specialist the R2 was a summary statistical measure of how well the estimated model “fitted” the actual data. With the advent of modern computing, researchers could run millions of econometric models – data mining – and come up with almost anything that they wanted.

There was a lack of awareness to engage in transparent model selection techniques and replication. Some referred to it as an exercise in eCONometrics. The task was to maximise the R2 even if the model was deeply flawed.

The problems escalated and reached a peak in the late 1970s when the inflationary outburst associated with the OPEC oil price hikes caused major forecasting errors in the macroeconometric models that had been developed by central banks, treasuries and other bodies (some private consulting firms etc).

It seemed that these models, which were extremely expensive to develop (some with thousands of equations) were useless and could be outperformed by single equation univariate processes. That is, a model based on past values of some variable in question. No theory – just inertia.

The impact of the evolving inflation was significant because it exposed fatal specification flaws in the extant models. The fact that they were mis-specified (including omitting key variables) was not discovered until one such missing, but important variable – the inflation rate started to exhibit a non-zero variance.

That is, a model can forecast well even though it is mis-specified as long as say the source of the mis-specification is not doing anything. So in the case of an omitted variable – this will not be an issue until that particular variables starts to move around. Then the flaws are exposed. That happened to the major consumption functions, for example, in the late 1970s.

The general-to-specific approach says that we don’t really know what the exact specification is and we need to search for it – including dynamic effects (time lags). So we start with a very general model of the process we are interested in and then perform a sequence of rigourous statistical tests on the model’s performance which then allows us to simplify the specification (eliminate variables or lags of variables that are of no consequence) until we achieve a parsimonious representation of the data.

The resulting model is false by definition because all models are false. We can never know the truth. How would we know it if we found it. The purpose of econometric modelling then is not to discover truth but to generate tentatively appropriate representations of the data that outperform all existing representations.

The specific-to-general model that characterised the traditional approach – including that used by Friedman and Schwartz – started with a very narrow specification – usually a static relationship between a few variables and then added variables in no systematic way as the modelling exercise continued with the aim of maximising the R2 statistic.

As Hendry et al. showed this was a very unsatisfactory way of proceeding.

In the past, when I have taught advanced econometrics to fourth-year students I have engaged in an exercise where we try to replicate some famous (influential) econometric study from first principles. The data is readily available and we usually found that the results of the study could not be replicated – usually because the model selection methodology was not transparent.

That meant that we could not work out how the researcher achieved the final form of the published equation because their reporting standards were lax.

More importantly, when the modelling was performed using the general-to-specific techniques on the same data, typically a very different model would emerge which would not support the theoretical proposition being countenanced (pushed) by the researcher.

Econometrics in the bad-old days was used to push a particular proposition from economic theory. So the orthodox economists would dodgy up some econometric model and conclude that their theory was right.

Friedman and Schwartz did just that.

In this 2004 paper from Econometric Theory – The ET Interview: Professor David F. Hendry – econometrician Neil Ericsson, Hendry’s former research officer and now a senior economist in the US Federal Reserve system, discusses all manner of topics with David Hendry, including the Friedman-Schwarz scandal.

Neil Ericsson said:

In 1982, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz published their book Monetary Trends in the United States and the United Kingdom, and it had many potential policy implications. Early the following year, the Bank asked you to evaluate the econometrics in Friedman and Schwartz (1982) for the Bank’s panel of academic consultants …

This led to the 1983 Ericsson and Hendry paper – a version of which you can access as – An Econometric Analysis of UK Money Demand in Monetary Trends in the United States and the United Kingdom by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz. It took

Hendry replied to Ericsson by saying that:

Friedman and Schwartz’s approach was deliberately simple-to-general, commencing with bivariate regressions, generalizing to trivariate regressions, etc. By the early 1980s, most British econometricians had realized that such an approach was not a good modeling strategy. However, replicating their results revealed numerous other problems as well.

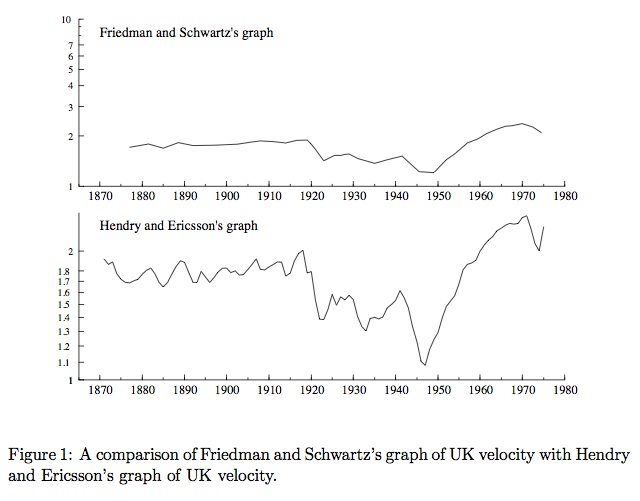

To which Ericsson noted “I recall that one of those was simply graphing velocity.”

In the Interview they reproduced a graph that shows how devious Friedman and Schwartz were in trying to push the Monetarist line. I reproduce it as the next graph.

Why is this important?

Think QTM! The theory of inflation relied on three things. First, that the central bank can control the money supply. Second, that there was continual full employment so the only way the economy can respond to nominal demand growth (MV) is via price rises and if MV accelerates there will be inflation. Third, that the velocity of circulation was stable.

Hendry told Ericsson that:

The graph in Friedman and Schwartz … made UK velocity look constant over their century of data. I initially questioned your plot of UK velocity-using Friedman and Schwartz’s own annual data-because your graph showed considerable nonconstancy in velocity. We discovered that the discrepancy between the two graphs arose mainly because Friedman and Schwartz plotted velocity allowing for a range of 1 to 10, whereas UK velocity itself only varied between 1 and 2.4.

The abuse and mis-use of scales on graphs.

But it went further. The formal econometric evaluation by Hendry, Ericsson and others at the time showed the work to be nonsense and misleading.

Hendry went on:

Testing Friedman and Schwartz’s equations revealed a considerable lack of congruence. Friedman and Schwartz phase-averaged their annual data in an attempt to remove the business cycle, but phase averaging still left highly autocorrelated, non-stationary processes.

Which in English says their estimated equations were rubbish.

Remember that this work was being published and promoted by Friedman and Schwartz at the peak of Margaret Thatcher’s reign in the UK. Central banks around the world had fallen for the Monetarist kool-aide and had imposed regimes called monetary targetting.

This involved the central bank announcing that it would target an x per cent growth in the money supply which translated into saying (because they claimed V was constant) into a nominal GDP growth rate of x per cent. Accordingly, if they wanted real growth to be 2 per cent and inflation to be 2 per cent, then x would be 4 per cent.

As Hendry puts it in the interview:

Margaret Thatcher – the Prime Minister – had instituted a regime of monetary control, as she believed that money caused inflation, precisely the view put forward by Friedman and Schwartz. From this perspective, a credible monetary tightening would rapidly reduce inflation because expectations were rational. In fact, inflation fell slowly, whereas unemployment leapt to levels not seen since the 1930s. The Treasury and Civil Service Committee on Monetary Policy (which I had advised in … had found no evidence that monetary expansion was the cause of the post-oil-crisis inflation. If anything, inflation caused money, whereas money was almost an epiphenomenon. The structure of the British banking system made the Bank of England a “lender of the first resort,” and so the Bank could only control the quantity of money by varying interest rates.

The UK Guardian ran a front-page editorial at the time (on December 15, 1983) – entitled “Monetarism’s guru ‘distorts his evidence'” which drew on an article in the body of the newspaper by one Christopher Huhne which “summarized-in layman’s terms” the critique by Ericsson and Hendry of the work by Friedman and Schwartz.

Friedman, in turn, was furious and wrote to Hendry requesting he disassociate himself from the Guardian article.

In the book by J.D. Hammond (1996) Theory and Measurement: Causality Issues in Milton Friedman ‘Monetary History, published by Cambridge University Press (page 199) you see the letter that Hendry wrote to Friedman on July 13, 1984. In part it said:

… if your assertion is true that newspapers have produced ‘a spate of libellous and slanderous’ articles ‘impugning Anna Schwartz’s and … [your] … honesty and integrity’ then you must have ready recourse to a legal solution.

Friedman never sued!

As Hendry notes in the interview:

One of the criticisms of Friedman and Schwartz was that is was “unacceptable for Friedman and Schwartz to use their data-based dummy variable for 1921-1955 and still claim parameter constancy of their money-demand equation. Rather, that dummy variable actually implied nonconstancy because the regression results were substantively different in its absence. That nonconstancy undermined Friedman and Schwartz’s policy conclusions.

As an aside it took Hendry and Ericsson eight years to get their working paper published in the American Economic Review after what they referred to as a “a prolonged editorial process”. Monetarism was dominant and the high-priests were clearly exerting as much pressure on editors of major orthodox journals to suppress research that was undermining the mainstream anti-government message.

Friedman and Schwartz has claimed (page 624) that their UK money demand model was constant (that is, stable in its estimated parameters);

… more sophisticated analysis … reveals the existence of a stable demand function for money covering the whole of the period we examine.

Stable equations are essential in econometrics because they can then be used for prediction. If the estimated relationship between X and Y is not stable then you cannot conclude with confidence that if you change Y you will get a predictable response in X.

Friedman and Schwartz (FS) knew that if they wanted to promote Monetarism (and they were the key promoters) then they had to produce stable equations – by hook or by crook (mostly crook).

What Hendry and Ericsson (HE) found is that FS did “not formally test for constancy, and many investigators would regard the need for the data-based shift dummy … spanning one-third of the sample as prima facie evidence against the model’s constancy.”

This refers to an ad hoc variable that FS used to ensure the equation looked constant. There was not theoretical reason to include such a “shift dummy”. The term dummy is apposite because it means there is no meaning to the variable. It is just a statistical fix to achieve some result. Sometimes a dummy has meaning (say when a major event occurs like an earthquake or a sudden policy innovation). But often it is just a fudge.

As HE showed – it was certainly a fudge in the FSs models. They wrote that FSs models were not constant once the evidence was properly considered and that the:

… inferences which Friedman and Schwartz draw from their regression would be invalid … [due to biases]

They also report a range of problems with the FS models.

In conclusion they say:

Taking this evidence together … [the FS preferred model] … is not an adequate characterisation of the data and is not consistent with the hypothesis of a constant money-demand equation … none of the relevant hypotheses could have been tested by Friedman and Schwartz … without their having obtained a rejection …

So overall the claim by FS that the money demand was constant which means that velocity of circulation was constant was rejected outright.

HE conclude that “at the heart of model evaluation are issues of model credibility and validity and the role of corroborating evidence”. They concluded that the work of FS was “lacking in credibility” and the evidence “inflations many of their infererences”.

Most nearly all the FS claims were rejected.

Conclusion

The point is obvious. There is no substantial support for the mainstream macroeconomics model. It has failed over and over to accord with events in the real world.

There is an historical litany of dodgy econometric studies that have been used to justify the ideological hatred for government intervention.

Fortunately, some of them have been grandly exposed – as in the case of Friedman and Schwartz. More often, however, they are not exposed as the frauds that they are.

The problems still resonate today because the Monetarist legacy – prioritising monetary policy and eschewing fiscal policy – still dominates the public debate. The world is worse of as a consequence. There is no grounds for this policy bias. Just pure ideology clouded by a smokescreen.

I wonder if Anna Schwartz ever reflected on her own dubious contribution to the debate.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill,

What a fascinating article, thank you so much. This and the one on Tarshis have been eye openers to me.

I would love to know more about your opinion of econometrics and how you use it in your analyses. It could be great if you could write more about it in one of your blog entries.

Best regards,

Javier Sánchez Barrueco

And today the main subjects that dominate the business media are the fiscal cliff and QE.

It’s a shame the book you reference is over $100 on ebay, I have always wondered why most economists today have such faith in the Quantity Theory of Money without themselves having explored the issue at all. I guess it is just an extension of the natural public appeal of “money printing hurts grandma’s savings”.

I’ve watched Friedman a number of times (a C-Span interview and part of his “Free To Choose” series), and each time I was struck by what is saw to be an almost childish demeanor on his part. He would get all excited over some pieces of clearly anecdotal evidence, and then proceed with exaggerated pleasure to extrapolate (obvious with no justification) some grand idea from them. In the TV series, there were also closing discussions among supposedly Very Serious People from the time, who with similar glee, would embrace whatever crackpot idea Freidman had advanced. I always came away from these with the question, would real adults have this conversation?

I’m curious if anyone else who has watched these has made similar observations..

_____

When I first commenced my study of macro (December, 2007; the crisis was just starting to blossom), I quickly got the feeling that no one in the economic community (that is, mainstream economists and their pundits) had a clue of what they were talking about. I had the feeling that something major must have gone very wrong in the field for this to be the case. A good bit later (though a full year before I found MMT), someone suggested that economists didn’t know what money was; that they simply assumed it, and went from there. This seemed to be something that if true was big enough to explain what I had been seeing to that point.

Friedman, as this blog points out, was enraptured with the idea of controlling the money supply to control the economy. Would it be a fair summary to say that Friedman’s belief largely stems from the fact that he didn’t understand what money was, and that this money supply he was controlling may have been a supply of something, but it was not a supply of money?

_____

Comment on the QTM: The deconstruction (and destruction) of the QTM here pretty much matches my own, except that in mine I try to make it more lay friendly. As to V, I break this out, separating borrowing from saving, as it’s probably not obvious to the average person that these are simply opposite ends of the same line. As to Q, in addition to unemployment, I break out productivity (which is usually omitted from QTM deconstructions), and I find that by specifying these four, I can better help people understand why “printing money = inflation” (the lay formulation of QTM) cannot be true.

The most fantastic of these reductions of course is unemployment, and so I find this requires a bit of further explanation. How could anyone possibly belief that unemployment doesn’t exist? And why should anyone advancing the claim that the mainstream actually believes this be taken seriously?

For this I list out (with brief explanations) the natural rate, structural unemployment (which I view as simply a supply side whitewash of the demand problem), leisure preference (though no one explains what’s so great about leisure when you’re broke), wage stickiness (my mortgage is pretty sticky too; that doesn’t seem to factor), skills atrophication (more supply side nonsense), and bad morals (which only the “little people” seem to suffer from). From my own (non-scientific) observations, I frequently add that based upon my review of lay articles coming out of the mainstream, a good half of the work of economists over the last three decades seems to have been at least tangentially focused on dismissing the idea of involuntary unemployment.

When I lay the QTM out like this, I’ve been pretty good at gaining lay converts to the notion that the QTM is nonsense.

_____

Obviously labor is but one among many cost inputs to the production process. Why then is labor singled out among them for such zealous attacks? What’s the obsession with this? Why aren’t other cost inputs met with such myopic focus?

Jan said:Bill!Excellent! Professor Lars Pålsson Syll-Malmö University writes in similar terms as you

about Neo-Liberalism as a purely political project and qouting one of your old favourites Michael Kalecki!All the best to you Bill and keep up the good work!

“The confidence fairy

http://larspsyll.wordpress.com/2012/07/15/the-confidence-fairy/

To many conservative and libertarian politicians and economists there seems to be a spectre haunting the United States and Europe today – Keynesian ideas on governments pursuing policies raising effective demand and supporting employment. And one of the favourite arguments used among these Keynesophobics to fight it, is the confidence argument.

Is this witless crusade againt economic reason new? Not at all. This is what Michal Kalecki wrote in his classic 1943 essay Political aspects of full employment :

“It should be first stated that, although most economists are now agreed that full employment may be achieved by government spending, this was by no means the case even in the recent past. Among the opposers of this doctrine there were (and still are) prominent so-called ‘economic experts’ closely connected with banking and industry. This suggests that there is a political background in the opposition to the full employment doctrine, even though the arguments advanced are economic. That is not to say that people who advance them do not believe in their economics, poor though this is. But obstinate ignorance is usually a manifestation of underlying political motives …

Clearly, higher output and employment benefit not only workers but entrepreneurs as well, because the latter’s profits rise. And the policy of full employment outlined above does not encroach upon profits because it does not involve any additional taxation. The entrepreneurs in the slump are longing for a boom; why do they not gladly accept the synthetic boom which the government is able to offer them? It is this difficult and fascinating question with which we intend to deal in this article …

We shall deal first with the reluctance of the ‘captains of industry’ to accept government intervention in the matter of employment. Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect which makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence. If this deteriorates, private investment declines, which results in a fall of output and employment (both directly and through the secondary effect of the fall in incomes upon consumption and investment). This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis. But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness. Hence budget deficits necessary to carry out government intervention must be regarded as perilous. The social function of the doctrine of ‘sound finance’ is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence.”

If velocity is constant, then a stocks and flow model is unnecessary. Another way to think about it is that the medium of exchange function of money can then be taken as a given, and what is left is the value store function.

Friedman was a journeyman economist who happened to be in the right place at the time that the bankers needed someone obscure to rise to the challenge.

True “freedom to choose” would include which money supplies to use for private debt. Then, though the banks might drive up prices in their money supplies, people could be immune using their money supplies. MMT says that the government’s authority and power to tax is all that is needed to back fiat. So why is it also required (one way or another) that we use fiat (or credit based on it) to pay private debts?

Dear Bill,

This is off topic and I apologise for that. Simon Wrenn-Lewis has a post today titled “The heterodox versus the superhuman representative agent” on his blog “mainly macro”. In this post he poses a question about the effects of a balanced budget increase in government spending at the zero lower bound on an economy and uses a microfounded analysis to provide an answer. He ends by asking whats wrong with this type of approach and whether heterodox economics provides a better one. I have to admit that I don’t know how MMT would approach this analysis after reading your blog for more than a year. Your blog is great by the way and I hope you are not offended by my assuming you are a “heterodox” economist.

Well anyway, I said I would ask an MMT economist and sometimes its best to go straight to the top. So if you or anybody could respond or point out the relevant blog posts it would be much appreciated.

I love Richard Koo’s book described it well: “Many mocked the supply-side reforms of Reagan and Thatcher as “voodoo economics” arguing that these policies were little more than mumbo-jumbo, and that Reagan’s arguments should not be taken at face value. Most economists in Japan also held supply-side economics including Reagan’s policy as “cherry-blossom-drinking economics.” This appelation came from the old tale of two brothers who brought a barrel of sake to sell to revelers drinking under the cherry trees, but ended up consuming the entire cask themselves, each one in turn charging his brother for a cup of rice wine, and then using the proceeds to buy a cup for himself.” – The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, p.4.

jbrown981.

I do not and could not, speak on behalf of Mr Mitchell but micro solutions when added together do not work at the macro level. So whilst one micro policy may sound fine, and be well intentioned, the cause and effect of them in multiples quickly become obvious. Especially the unintended consequences.

Without the correct macro policies in place even the best micro policies cannot work.

Thank you Bill 40.

V=Perception of value, the most variable and subjective of all. A piece of art with a Q of 1 and a high perception of value will have a higher price.

“Not only was the food lousy, but the portions were small.” Woody Allen economics

An accelerating V for no logical reason may indicate bubbling of P or Q.

Mom worked on The Boardwalk for a speed painter. “Investors” tried to value the art. “Do you think two bushes is worth more than a tree and a picket fence?”

What do you think of the IMFs latest plan to take wealth from the Irish and give it to the credit banks so they can waste the stuff like the good old days.

@Bill

You seem like a honorable guy but I can’t understand your support for the CB system

They are clearly the enemy.

We need a Andrew Jackson like figure that can also produce mountains of Greenbacks and take leverage away from these 19th century Free Banks who also have control over monopoly currency via the CB network.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La4JEwyr094&t=19m51s