In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

UE is needed rather than QE

And what is UE you might ask? Unemployment easing! As the major economies start to slow again (as fiscal stimulus is withdrawn prematurely), the calls are coming thick and fast for more quantitative easing. The Bloomberg editorial (June 8, 2012) – The Key to a Stronger Recovery: A Bolder Fed – was representative of this renewed call for the central banks to somehow stimulate aggregate demand to the tune of several percent of GDP in many nations. Like the latest bailout in Europe, the call for more QE is predictable. Neither initiative addresses the real problem with the relevant policy tool or change. What is needed is something much more direct. Why don’t we have a policy of unemployment easing (UE) where the treasury departments, supported by their respective central banks, immediately set about directly creating jobs and reducing the unemployment rates around the world. Putting cash (wages) into the hands of those that are most constrained (the unemployed) will do much more good for the economy than doing portfolio swaps with banks who will not lend to thin air! So we need UE not QE.

It didn’t take long

The following screen capture of the latest headlines was in the sidebar of today’s UK Guardian Economics Page.

As I noted yesterday, the Spanish bank bailout will not forestall the crisis for very long. Already, within 24 hours, the “markets” have worked out that it doesn’t address the problem.

UE rather than QE

In the Bloomberg Editorial noted in the introduction we read that:

The Fed ought to get off the fence. At the next meeting of its policy-making committee on June 19-20, Bernanke and his colleagues should decide on a new program of monetary easing … we think the case is stacked pretty strongly in favor of more quantitative easing — the Fed’s unorthodox (and controversial) method for driving long-term interest rates lower by buying government debt.

Why would they advocate that strategy?

1. “the economy is now growing too slowly to make significant inroads on unemployment”.

2. “Jobs figures released last week were especially disappointing”.

3. Inflation is “falling” and “Long-term inflation expectations … they’re low and stable”.

Apparently, all the risks are “tilted to the downside” (reference: the incompetence of the Eurozone leadership) and:

U.S. fiscal policy is another danger. If the economy falls over the so-called fiscal cliff at year’s end, count on a second recession. If Congress heads that off, fiscal policy is likely to subtract demand from the economy next year.

We have had Rogoff-style 80 per cent debt ratio thresholds rammed down our throats for a few years – nothing has happened as sovereign (currency-issuing) nations have passed the threshold and certainly Japan (at 230 per cent is way out there).

So the latest scare-contrivance is the so-called “fiscal cliff”. The US economy will only go back into recession if policy makers believe that an expanding budget deficit is somehow dangerous and start mimicking the Europeans and British and impose fiscal austerity.

The reality is that there should be more fiscal stimulus at present in the US not less.

But the Bloomberg Editorial is adamant:

Demand is growing more slowly than the Fed believed, inflation is falling below target, progress on unemployment is glacial, and the risks are loaded on the negative side. What’s the Fed waiting for?

I agree with that assessment but would answer the question in this way: The Fed should be urging the US Treasury to embark on a program of Large-Scale Unemployment Easing which could begin immediately with the announcement that the US Government will fund anyone who wants to work at a decent minimum living wage. They might operationalise such a policy at the local level but fund it nationally.

They could also consider the challenges of the future – public health, climate change, renewable energy, public education, public transport and other infrastructure and broaden the employment offer to well-paid, highly skilled persons who are seeking jobs.

The call for more QE is waste of effort. While the previous interventions in this regard were benign despite the hysteria from the critics, there is no documented evidence that the strategy was very stimulatory. The research from the US Congressional Budget Office, however, has categorically demonstrated the effectiveness of the fiscal interventions.

On March 29, 2012, the Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke concluded his four-part lecture series at George Washington University. The title of the fourth lecture was – The Aftermath of the Crisis. The full video is available HERE but the Transcript – saves you sitting through the talk (which was interesting).

He talked at length about QE. He noted that by December 2008 “conventional monetary policy was exhausted” (that is, the short-term interest rate was near zero) and so the Federal Reserve sought to introduce “non-conventional” monetary policy initiatives:

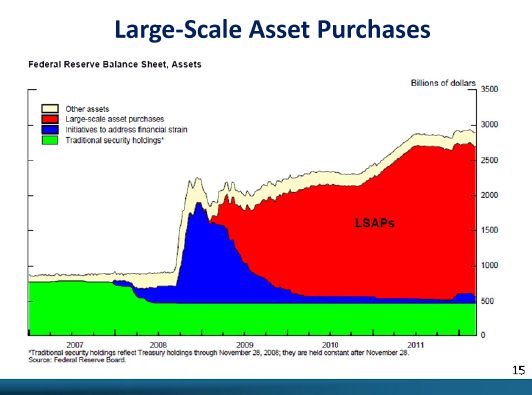

And the main tool that we’ve used is what we call in the–within the balance of the Fed, the large-scale asset purchases or LSAPs, more properly known in the press and elsewhere as quantitative easing, or QE. I won’t get into why I think LSAPs is a better descriptive name, but in any case, I’ve had to bow to the common usage.

The reference to bowing to common usage can be traced back to January 13, 2009 when he gave a speech at the London School of Economics – The Crisis and the Policy Response. In that speech he said:

The Federal Reserve’s approach to supporting credit markets is conceptually distinct from quantitative easing (QE), the policy approach used by the Bank of Japan from 2001 to 2006. Our approach–which could be described as “credit easing”–resembles quantitative easing in one respect: It involves an expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet. However, in a pure QE regime, the focus of policy is the quantity of bank reserves, which are liabilities of the central bank; the composition of loans and securities on the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet is incidental. Indeed, although the Bank of Japan’s policy approach during the QE period was quite multifaceted, the overall stance of its policy was gauged primarily in terms of its target for bank reserves. In contrast, the Federal Reserve’s credit easing approach focuses on the mix of loans and securities that it holds and on how this composition of assets affects credit conditions for households and businesses. This difference does not reflect any doctrinal disagreement with the Japanese approach, but rather the differences in financial and economic conditions between the two episodes. In particular, credit spreads are much wider and credit markets more dysfunctional in the United States today than was the case during the Japanese experiment with quantitative easing. To stimulate aggregate demand in the current environment, the Federal Reserve must focus its policies on reducing those spreads and improving the functioning of private credit markets more generally.

So the LSAP – or credit easing in 2009 is quantitative easing in 2012. Small point though.

The LSAP policy was intended to “influence longer-term rates” and involved the Federal Reserve undertaking:

… large scale purchases of Treasury and GSE mortgage-related securities … the securities that the Fed has been purchasing are government-guaranteed securities, either Treasury securities … or the Fannie and Freddie securities, which recall were guaranteed by the U.S. government after Fannie and Freddie were taken into conservatorship.

He offered the following slide to show the impact of the LSAP relative to the normal Federal Reserve holdings of government debt (which said in “normal circumstances, the Fed always owns a substantial amount of U.S. Treasuries” anyway).

The logic of the LSAP was clear:

The basic idea is that when you buy treasuries in GSE securities and bring them on to the balance sheet, that reduces the available supply of those securities in the market. Investors want to hold those securities and–or they’d be willing to hold a smaller amount, they have to receive a lower yield. Or put in another way, if there’s a smaller available supply of those securities in the market, they are willing to pay a higher price for those securities, which is the inverse of the yield.

So they wanted to lower interest rates on the assets purchased which would, in turn, create spillover effects onto other corporate bond rates (increasing the demand and lowering the yields).

The aim was to “lower yields across a range of securities” because they believed “as usual, lower interest rates have supportive stimulative effects on the economy”.

While it might be “conventional wisdom” (as usual) that lower interest rates are stimulative the evidence is less clear. There are several factors that have to be taken into account. The state of private balance sheets, the state of the economy, the distributional effects of rates changes on creditors and debtors, etc.

The mainstream belief that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantititative easing provides those reserves.

Mainstream macroeconomics create the illusion that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

This is clearly an incorrect depiction of how banks operate in the real world. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

The major formal constraints on bank lending (other than a stream of credit worthy customers) are expressed in the capital adequacy requirements set by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) which is the central bank to the central bankers. They relate to asset quality and required capital that the banks must hold. These requirements manifest in the lending rates that the banks charge customers. Bank lending is never constrained by lack of reserves.

Further, when times are tough and households are intent on increasing their saving rate and reducing their consumption growth, which, in turn, puts a brake on investment plans by firms (they will have enough capacity to produce to the current diminished demand levels), the demand for credit is not particularly sensitive to interest rate changes.

Slightly lower interest rates may lower the cost of borrowing but if the expected return over the lifetime of the loan (of the productive asset purchased) is unfavourable then there will not be an upsurge of demand as a result of quantitative easing interventions. That is exactly what we have been witnessing over the last three years.

The Federal Reserve Chairman’s lecture yielded some other interesting insights. The question that came up in the hysteria when the interventions were first announced, in part, focused on how these purchases were transacted? Or in more common parlance “where did the money come from”? Taxes? Issuing Debt?

The Federal Reserve Chairman was very specific in answering his own question:

“Well, the Fed is going out and buying $2 trillion of securities. Well, how do we pay for that?” And the answer is that we paid for those securities by crediting the bank accounts of the people who sold them to us. And those accounts at the banks showed up as reserves that the banks would hold with the Fed. So the Fed is a bank for the banks. Banks can hold deposit accounts with the Fed essentially, and those are called reserve accounts. And so as the purchases of securities occurred, the way we paid for them was basically by increasing the amount of reserves that banks had in their accounts with the Fed … Sometimes you hear that the Fed is printing money in order to pay for the securities we acquire, and I’ve talked about that in some–you know, in some–in giving some conceptual examples. But as a literal fact, the Fed is not printing money to acquire the securities.

I often get criticized (by E-mail) for stressing the fact that the Federal Reserve was not printing money during this period. Apparently I would garner more support for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) ideas if I conceded the “facts” and made it easier for those indoctrinated with mainstream macroeconomic thinking to cross the MMT line.

It reminds me of the debate in the 1930s between Keynes and his (sympathetic) critics who urged him to abandon the inverse relation between employment and the real wage rate based on marginal productivity theory that dominated Chapter 2 of the General Theory. This use of “marginal productivity theory”, a centrepiece of the dominant neo-classical view was controversial.

While it is the topic of another blog – the rationale of the criticism is that by building on the then received “wisdom”, Keynes would open his theory up to hijacking – back into the received “wisdom”.

Keynes resisted the critics and Chapter 2 is what it is. Not long after the General Theory came out what became known as the Neo-classical-Keynesian synthesis emerged which bastardised many of the unique features of the General Theory and made way for all the spurious notions that form the mainstay of the mainstream approach to this day (for example, crowding out; fiscal policy ineffectiveness etc). In other words, the critics were correct.

The MMT developers have discussed this issue at length for the last 18 or so years and we hold the view that terminology is power and as such we don’t want the essential ideas to be blurred through use of conventional terminology which is of the loaded variety.

Anyway, as the Chairman stressed – the Federal Reserve were not in this instance – printing money.

So what were they doing? In this blog from March 2009 – Quantitative easing 101 – I outlined how QE works and why it would not be successful.

The Federal Reserve were in fact swapping reserve balances for the assets they purchased. If you want to learn more about the role of reserves please read these blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

The transactions they engaged in were electronic entries in the same way that most government spending is made operational by a series of electronic entries to the banking system. There are no financial limits entailed in that sort of activity. There can be voluntary limits imposed by the players themselves for political and ideological reasons.

But in recognising that distinction, we open a new avenue of debate when the government makes a political statement such as “we have run out of money” or “we cannot afford to pay decent unemployment benefits” or whatever. If the population broadly understands that a sovereign government can never run out of money and can always make these electronic transactions then the questions they might ask their politicians will change and force the latter to be more accountable for their political choices.

On reserve balances, the Chairman said that:

Those are the accounts that banks, commercial banks, hold with the Fed and their assets to the banking system and their liabilities with the Fed, and that’s basically how we pay for the–for those securities. And so the banking system has a large quantity of these reserves, but they are electronic entries at the Fed. They basically just sit there. They’re not in circulation. They’re not part of any broad measure of the money supply. They’re part of what’s called the monetary base. But again, they’re not–they certainly aren’t cash. Then there are other liabilities including Treasury accounts and a variety of other things that the Fed does. We act as the agent, the fiscal agent for the Treasury. But the two main items you can see are the notes in circulation and the reserves held by the banks.

That should be very clear and should cure you of all the mythology that you will read in mainstream macroeconomic textbooks where the concept of a money multiplier is central and a transmission vehicle for the Quantity Theory of Money – which says that increasing the money base will cause inflation because the money supply rises.

Please read my blogs – Money multiplier and other myths and Money multiplier – missing feared dead – for more discussion on this point.

Note that dismissing the monetary multiplier theory does not, in itself refute the QTM explanation of inflation. All it does is break the transmission mechanism between the central bank increasing the monetary base and the money supply rising.

I also remind readers of an interesting Working Paper (No. 292) from the Bank of International Settlements (November, 2009) – Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal – which I have referred to in the past.

The authors are very clear:

… changes in reserves associated with unconventional monetary policies do not in and of themselves loosen significantly the constraint on bank lending or act as a catalyst for inflation …

I refer you back to the two blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion on that point.

The BIS paper also reminds us that:

… central bank balance sheet policies need to be viewed as part of the consolidated government sector balance sheet. The main channel through which they affect economic activity is by altering the balance sheet of private sector agents, or influencing expectations thereof. As a result, almost any balance sheet policy that the central bank carries out can, or could be, replicated by the government; conversely, anything that the central bank does has an impact on the consolidated government sector balance sheet.

Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank and Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on this point.

The question that arises is one of effectiveness. Treasury fiscal operations which directly inject aggregate demand into the spending stream are likely to be effective than asset swaps which lead to an increase in reserves but do nothing to improve the confidence of the households and firms.

After all, quantitative easing does not lead to job offers as a matter of course. Fiscal policy can be expressed in terms of explicit job offers and you cannot get a more direct stimulus than that.

This is why I consider a Job Guarantee to be the first necessary plank in any government policy. By operating as an automatic stabiliser it guarantees that a certain level of income support will be available in return for productive activity – at all times.

Despite there being no real evidence, the Federal Reserve Chairman claimed that the quantitative easing policy:

… was generally successful. For example as you probably know, 30-year mortgage rates have fallen below 4 percent, which is a historically low level, but other interest rates have fallen as well …

There is no doubt that mortgage rates fell in 2009 – the announcement came in November 2008 and the purchases started in January 2009. But they were falling before the US Federal Reserve started the purchasing program.

At any rate, we can agree that the program lowered long-term rates. But there is no hard evidence that this provided a major stimulus to demand. There is a lot of evidence to the contrary that likely interest-sensitive spending components have been fairly insensitive in the face of persistently high unemployment and low confidence.

Conclusion

The emphasis on monetary policy as being the vehicle to provide the primary stimulus to ailing economies instead of fiscal policy is contrary to the evidence and reflects the ideological shift that occurred under Monetarism and was refined over the, more recent, inflation targetting era.

Early in the crisis, the reliance on monetary policy to arrest the collapse in aggregate demand around the world only made the real crisis worse although it did stabilise the financial sector, for a time.

Until policy makers realise that fiscal policy is a much more effective way to stimulate aggregate demand this crisis will continue to grind on. I think we need a period of unemployment easing not quantitative easing.

That is enough for today!

“At any rate, we can agree that the program lowered long-term rates.”

That’s all it did.

Do you know why economists get so excited about lowering interest rates? I have yet to see a business proposition stall because the interest rate was 0.25% higher or lower. Modern business works on pay back periods counted in months not years – a trend that has accelerated as business has become more uncertain and more service driven.

Where are the investment plans that are so long term that they are affected by the odd quarter of a percent shift in interest rates?

Looking at the recent balance sheets of the Australian major banks, you see that the official reserves, i.e. their deposits with the RBA, are very small or negligible, although they seem to have some other financial assets apart from deposits. Also, their loans, which are the major part of their assets, are quite lot higher than their deposits. The deposits seem to be 2/3 to 3/4 of their loans. They make up the difference with borrowings.

Does this mean that the Australian banks are significantly different to the American ones?

Am I reading the balance sheets correctly?

Where has all the endogenous money gone?

Thanks for another insightful and easy to understand explanation

Great analysis.

Little in the way of real solutions – beyond MMT theory.

Like exactly what policies are going to achieve what is NEEDed?

We already know conventional policy(ZIRP) does less than nothing.

And that QE does nothing but drive up non-spendable excess reserves.

We already know that the “fiscal-space” MMT solution involves government spending directly on the job-creation solution.

But…… we can’t get there from here.

So-called ‘self-imposed constraints’ are what we call the law.

So, in order to get into the realm of :

“”where the treasury departments, supported by their respective central banks, immediately set about directly creating jobs and reducing the unemployment rates around the world….. Putting cash (wages) into the hands of those that are most constrained (the unemployed)…””

So, here’s the thing, Bill.

There IS a proposal to do exactly that.

It is called the “National Emergency Employment Defense (NEED) Act of 2011”.

It was introduced into the US Congress as H.R. 2990 by progressive Congressman Dennis Kucinich on September 21 of last year.

The questions I have are two:

1. Why do MMT proponents not support the advancement of the law(H.R. 2990) that promotes and enables the public policies that MMT is advocating?, and

2. What goals of the MMT school can not be achieved by the passage of the Kucinich Bill?

If not the Kucinich Bill, then what?

Thanks.

Politically, Steve Keen’s “A Modern Jubilee” (scroll down) is more tenable. Conservatives and libertarians are opposed to increases in the size of government but simply handing out new money to the entire population, including non-debtors, can be done with the same size or even smaller government. I don’t recall much opposition to GW Bush’s “stimulus checks”, for example.

I’d be just as happy to see the money loaned out [to all creditworthy citizens normally resident for tax purposes] at a similar rate of interest that the banks pay, with the proviso they pay down their old debts first, before spending on new goods. 2-5000 a month should do the trick.

“we hold the view that terminology is power and as such we don’t want the essential ideas to be blurred through use of conventional terminology which is of the loaded variety.”

Indeed, and surely the greatly over-used word ‘markets’ ought to be replaced.

Dear Joebhed,

H.R. 2990 is very interesting, but it doesn’t seems to include a job guarantee (JG). A JG is the means MMT theory has developed to control inflation while enabling full employment. H.R. 2990 does have provisions to stimulate the economy but stimulus by itself may not lead to full employment (see Tcherneva article http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00346764.2011.577348#preview).

Also, H.R. 2990 does provide for ample education funding but, if unemployment is due to a slack in demand and not only because of a skill mismatch increases in education will not lead to full employment.

Best,

Justin

UE not QE…superb

In fiat non convertible currency system every man can get paid who is willing to work .

Somehow the current system prefers to pay people not work than make an effort to find them work .

This set up is neither Creative nor Godly . Any ethical/moral human being would know that paying the unemployed not to work is shirking his responsability to his fellow man and creator .

Whether it is laziness or ignorance or misguided evil that is maintaining the status quo …the first step is an easy one : Just give it a try ..betting on human ingenuity in a righteous cause will deliver returns a thousand fold beyond our current blinkered imagination.

This is not a political choice but a moral choice .

Any ethical/moral human being would know that paying the unemployed not to work Walid M

Who’s being paid not to work? People can still take care of their kids, volunteer their time, work around the house, the garden, etc.

Moreover, there is nothing about our money system, usury for counterfeit money – so-called “credit” – that is godly. The population deserves restitution for theft – not government make work.

Would someone please help me resolve my problem with the following: if reserves are not cash nor can they be lent out (MMT), why do banks ,in a QE operation ,offer their negotiable bonds to the Fed in exchange for apparently useless reserves? (I’m talking about reserves in excess of interbank “bookkeeping” needs).

why do banks ,in a QE operation ,offer their negotiable bonds to the Fed in exchange for apparently useless reserves? (I’m talking about reserves in excess of interbank “bookkeeping” needs). JB

Great question!

My guess: Because the Fed overpays for them?

To Justin Holt.

Thanks.

I don’t have the $36 to read through Pavlina’s article, perhaps it is otherwise available. I have seen it quoted elsewhere.

Regarding controlling inflation in a full-employment economy, I refer you back to the systems-dynamics-based. macro-economic monetary system modeling work of Prof. Kaoaru Yamaguchi of Japan’s Doshisha University.

http://www.old.monetary.org/yamaguchipaper.pdf

Dr Yamaguchi is the Director of the first Green MBA Program in Japan.

MMT is interesting but it doesn’t include the recapture of the national monetary system from the global private central bankers and for some progressive(?) reason leaves the money power in the hands of private corporations through endogenous money principles.

Can you say Occupy Wall Street frustrations.

I believe in full employment as a socio-economic construct.

I support Bill’s and others’ efforts to define a long-off detail of things like how much money the BIG should be or the wage-rate of the government created jobs.

The JG is a great socio-economic objective to have and we all agree that it must be pursued.

But it’s no different today than when I told my Dad I wanted peace, justice, and a sustainable planet in my time.

“If you do not control the money system, then you have no control over achieving any of those goals.”

So, I’m out for public control of the money system, and then peace and justice and sustainability.

I think that trying to define the JG at this stage of MMT advancement is an unnecessary distraction to the discussion. Merely identifying it as a goal of whatever legislative proposal MMT eventually becomes is sufficient.

Neither of us get ahead without change.

After the books are written, we will NEED an MMT legislative proposal.

Then we can see where we stand.

Thanks.

“Would someone please help me resolve my problem with the following: if reserves are not cash nor can they be lent out (MMT), why do banks ,in a QE operation ,offer their negotiable bonds to the Fed in exchange for apparently useless reserves? (I’m talking about reserves in excess of interbank “bookkeeping” needs).”

Because they were selling anyway for various liquidity reasons. There is always a continual turnover of these Bonds. That is what creates the liquidity in that market.

If the Fed turns out to be the buyer then overall the system will be short of bonds and some people who were looking to *buy* them will be disappointed.

ISTM that the effect of QE is on the frustrated buyer of bonds, not the seller. So the question is what did that buyer do instead? And since they were in the market for secure savings it is unlikely they decide to buy a yacht instead.

Bill – you state:

“If the population broadly understands that a sovereign government can never run out of money and can always make these electronic transactions then the questions they might ask their politicians will change and force the latter to be more accountable for their political choices.”

I have come over to MMT in the past couple of years, but when I am given a chance to explain its features to more intelligent folk (who know that “common sense” is never enough), I am invariably asked the following:

What is to prevent vote-pandering politicians from making all manner of promises in the spending arena, with little regard to the (potential) inflationary impact? I.E. at some point there is enough currency in circulation such that there is “full” employment and productive capacity is close to 100% so how do you turn off the spiggot? Obviously this is the role for taxation, but again it is difficult to sell that politically.

So we are left with the age-old conflict between sound policy and the need to get elected …

I just love the implied idea that governments can simply manipulate at will without any ill side effects that may not show up immediately but maybe only after years which is actually the case with the present crisis which is the result of manipulations in so many past years.

It seems that central planning is connected to just to great a good feeling for all the decision makers to forgo it.