I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

How large should the deficit be?

Today I am in Melbourne (my home town) presenting a workshop on skills development for the new green jobs economy which is a joint Victorian Government/Brotherhood of St Laurence show. But that is not what I am writing about here. Regular readers of billy blog will know that when I talk about budget deficits I typically stress two points: (a) that the Government is not financially constrained and therefore all the hoopla about debt and future tax burdens are just a waste of time. But just because the Government can buy whatever is for sale by crediting relevant bank accounts doesn’t mean they should not place limits on the size of the deficit; and so (b) given the federal deficit “finances” private saving, it should therefore be aim to “fill” the spending gap left by the private desire to save. If the Government does that then it can maintain full employment and price stability and move towards a more equitable society. So it is of importance that we have some idea of the size of this spending (or output) gap.

The first thing that the Government has to understand, which it currently does not – if all its “tough budget talk” is a reflection of their state of cogniscance – is that the size of the deficit is a totally useless thing to become obsessed with. The size of the deficit – which is just an accounting statement after all – is not a viable or legitimate policy target.

The fact that the Government is still thinking it has to worry about the particular deficit figure reflects the destructive neo-liberal overhang that still dominates macroeconomic policy.

I am reminded here of a statement that the doyen of Monetarism, Milton Friedman made when talking about so-called Balance of Payments problems. He said …. more or less … that we would all be happier if governments did not calculate or publish balance of payments data.

While the suppression of information was a hallmark of the previous federal regime. For example, their refusal to publish wage data once WorkChoices was imposed on us was one of many examples of the way they tried to censors information and restrict what researchers such as me could do. Censorship is, therefore, not a palatable option. But I have some sympathy with the view that if we stopped publishing the deficit data we would realise the sky isn’t falling in and might actually start focusing on the problem at hand.

In yesterday’s blog – What if the IMF is right? – that problem was fairly starkly laid out. The entire World economy is in the grip of a very substantial recession which in some countries is bordering on depression. For Australia, the backlog of primary commodity orders has helped delay the onset of this destructive tide but now it is clear that our economy is falling fast. All those years of fiscal drag – the surpluses that were praised – are now coming back to haunt us. During those years of surplus, we failed to build structures that would really insulate us from the worst ravages of recession.

We allowed our public infrastructure to degenerate; we ran down our higher education and research capacities; we allowed hundreds of thousands of workers to languish in unemployment and promoted legislation that created record levels of underemployment – the low-skill, low-wage, low productivity path to job creation. The surpluses undermined the nation’s future and imposed huge costs of certain segments of the population who had to carry the burden of persistent labour underutilisation.

When we could have creatively implemented a Job Guarantee which would have re-engaged all those we were leaving behind. This would have allowed the nation to integrate a forward-looking skills development framework within a paid-work environment. Instead, we chose to run the disadvantaged around in circles of Centrelink office abuse; pernicious work tests; and futile training courses divorced from any real paid work environment. It was stupid policy and wasteful of the potential of the future generations.

Far from deficits “mortgaging the futures of our children”, it was the surpluses that undermined their future by wasting the opportunities each day for people to re-skill, to work and accumulate savings. This would have allowed them to develop risk management systems which would have increased their capacity to cope with economic uncertainty. Now we are back in recession – as we were always going to be at some point – and we have hundreds of thousands of workers without sufficient skills to cope; many households so indebted that they are highly exposed to the slightest changes in their economic circumstances ; and a Government without any real policy structures in place to lead the nation out of this.

And now on a daily basis we have to endure this nonsensical debate about whether the deficit is too large already and that a tough budget is going to be necessary to keep the budget deficit at a minimum and that hard decisions are going to be made to ensure the deficit doesn’t blowout and all the rest of the absurd rhetoric that dominates the so-called policy debate.

Journalists and business economists (mostly bankers who clearly have vested corporate interests such that their comments should be taken with a grain of salt mostly) feed this conservative torrent daily with their use of terms such as “runaway deficit”; “deficit blowout”; “debt mountain”; “deficit spike”; “unchecked borrowing” and other nomenclature. All of this is designed to raise alarm and frighten us back into the conservative hole that we have been cowering in for the last several years. While we were cowering we stood by and allowed our national government to abuse office by maintaining high levels of labour underutilisation and then punishing the victims of their policy folly with their pernicious welfare-to-work type policies.

So in the coming budget the size of the deficit should not be a target. The target should be on correctly estimating the spending gap and filling it in the most effective way possible. By that I mean creating as many jobs as are necessary to ensure that we finally return to full employment (by which I mean 2 per cent or less official unemployment and zero underemployment) while also ensuring that government spending does not create production bottlenecks which could generate inflationary biases once higher rates of capacity utilisation return. As I have argued relentlessly, the first place to start is to generate “loose” full employment via a Job Guarantee.

The fiscal injection needed to accomplish that policy goal is the minimum necessary to get us back to full employment and represents a considerably smaller impulse than that required if the Government tried to create the same number of jobs through private market stimulus. After all, the Job Guarantee requires only that the Government offer a job to anyone who wants one at the current minimum wage. By definition, the unemployed are not required by the private sector. There is no demand for their services and so no market pressure occurs as a result of the Government offering them a job. The extra spending the JG workers might make would be fairly trivial given we are supporting them on unemployment benefits anyway. Once you have the safety net Job Guarantee in place then you can think about what other public investments are desirable.

In the current debate I have heard no statement from the Prime Minister, the Treasurer, the Finance Minister, the Minister for Employment nor any of their Opposition counterparts as to what they think the spending gap actually is. Lots of hot air about the size of the deficit but no discussion at all about the extent to which the economy needs further net government spending. That lacuna says it all for me. The recession is being politicised and this represents a clear failure of our political process to deliver responsible government policy.

If we are facing the worst recession since the 1930s and some countries are bordering on being in depression, then it is clear that any federal budget will have to be very expansionary. I read in the Australian the other day that the best advice for Government was to just hold still and try to achieve “balance”. To try to build a path back to a budget balance into this coming budget, which is the advice being given by all and sundry, would be the height of irresponsibility. We will need a much larger deficit as a percentage of GDP than we have envisioned to date. How large? Well that depends on what we think the spending gap is going to be and for how long it is likely to persist. That should be the topic of attention not the size of the deficit.

First, we know that the private sector (particularly those heavily indebted households) are now saving like they haven’t for years. The most recent National Accounts verifies a sharp rise in saving out of disposable income. A good proportion of the fiscal injections to date will have reinforced this trend as households struggle to restructure their precarious balance sheets and to get some risk margin back into their lives.

When the private sector increases its saving rate, aggregate demand (spending) falls, inventories accumulate, and firms reduce production levels and employment. If uncertainty increases as the employment growth falters and unemployment starts to rise, then people may try to save even more to increase their security. The problem is that this makes the situation worse – the so-called “paradox of thrift”.

The only way out of this malaise is for the Government to use it unique fiscal capacity to fill the void. Despite what the conservatives say – there is no other show in town!

What is our best guess of size of the output or spending gap? Well my blog yesterday – What if the IMF is right? – provided some of the parameters that might help us generate a rough estimate.

First, if the IMF output growth projections for Australia are at all accurate then we will contract by -1.4 per cent this year and grow moderately by 0.6 per cent next year. I actually think their projections are optimistic. The IMF have been revising their forecasts down continually over the last few years as the crisis deepens. This, of-course, indicates that they really do not have a good feel for what is happening and so I expect their latest forecasts will probably be revised down further, particularly the 2010 expectations.

In yesterday’s blog – What if the IMF is right? – I showed that Labour force growth is running at about 1.8 per cent per annum at present. This will rise to around 2 per cent at higher levels of activity. Further, while Labour productivity growth (that is, GDP per person employed) is wallowing around 0.25 per cent per annum at present this should rise to around 1.5 per cent (that is, GDP per person employed) as the economy recovers. So you already know that if you want the unemployment rate to remain constant then GDP growth has to be around 3.5 per cent per annum at a minimum.

But, while I like the article in the Melbourn Age today by Tim Colebatch, I do not agree that this is the full employment GDP growth rate at present. It is the long-run growth rate that will stop the unemployment rate from rising from where it is right now! And that is saying nothing about the huge overhang of underemployment that we will be left with once this recession is over.

Remember that we started the recession (that is, the rise in official unemployment) in February 2008 with a labour underutilisation rate of around 9.0 to 9.5 per cent, roughly equally divided between official unemployment and underemployment. In the first three months of 2009, this rate has risen to around 11.5 according to our latest CofFEE Labour Market Indicators.

So once growth resumes you are left with a huge overhang of slack in the labour market, even if the GDP growth rate is sufficient to absord all new entrants to the labour market (labour force growth) and the lower employment requirements that accompany labour productivity growth.

So we are going to have to run GDP growth above the long-run required GDP growth (which may be around 3.5 per cent per annum) for some time to mop up the huge pools of unemployment. That is why a Job Guarantee is such a sensible policy. It absorbs the labour slack into public employment when the economy is in a downturn and allows an easy transition back into the “market sector” once growth resumes. But you do not have a huge pool of workers doing nothing for long periods of time as the economy struggles to grow again. For the time they are in the Job Guarantee pool they are adding value to the economy (via various community development and environmental care service jobs) and maintaining their families on the wages they earn.

So the concept of an output gap varies depending on what your target unemployment rate is and the path that the economy has taken to get to where you are right now. While the steady-state full employment output growth rate is likely to be around 3.5 per cent once things settle down again, in the interim, the output gap is much larger than that and so requires a commensurately larger fiscal response.

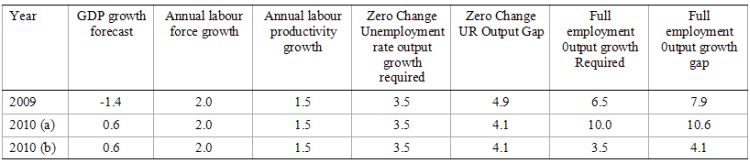

The following table which simplifies the issue a bit provides some guidance of the relevant magnitudes. In 2009, if we were aiming to achieve the long-run steady state growth path we would have to run GDP growth at 3.5 per cent per annum. Given the IMF forecast of -1.4 per cent, then for the unemployment rate to stay unchanged (and I am assuming it was around 5 per cent at the start of 2009), then we have a 4.9 per cent output gap at present.

But if you wanted to judge the gap by what would be required to restore a full employment unemployment rate (which I am assuming is 2 per cent and am abstracting from the extra hours of work you would need to generate to eliminate underemployment) then you would have to run GDP output growth in 2009 at around 6.5 per cent which means that the Full Employment output gap is around 7.9 per cent.

Of-course, it would be difficult to make that transition within a year unless you used direct public sector jobs creation. But the point is to demonstrate how much of a spending gap exists at present if we aim for full employment.

The situation gets more complex when we consider 2010. So 2010 (a) shows what might be the case if we hadn’t solved the rise in unemployment in 2009 whereas 2010 (b) shows what the output gap would be if we had have restored full employment in 2009. The simulation is of-course problematic because if we had have solved the problem in 2009 then the IMF forecast for 2010 of 0.6 per cent growth would have to be significantly increased. So the way of thinking about it is to assume we are actually in 2010 and the world is one year further into a recession. I estimated yesterday that the unemployment rate would rise to 8.5 per cent if the IMF forecast was correct for 2009 (although I used lower labour force and labour productivity growth forecasts for that analysis – which means that the 8.5 per cent unemployment rate projection is conservative if the underlying supply growth is higher).

So if you wanted to stop the unemployment rate from rising above say 8.5 per cent in 2010 – that is, just hold the fort, and if the IMF output growth projection is sound (0.5 per cent), then the output gap would be 4.1 per cent. However, if you were starting 2010 with an unemployment rate of 8,5 per cent then you would be facing a Full Employment output gap is around 10.6 per cent.

So the longer the Government allows the recession to deepen the harder is the way out!

What does this mean for the deficit? The projected budget deficit for 2009-10 has been estimated to be around $50 billion. The IMF are currently basing their output growth forecasts on a projected budget deficit of around 2.2 per cent of GDP. Accordingly, if you are happy with the Government just holding the unemployment steady at its current rate and not doing anything to reduce underemployment then I agree with Tim Colebatch that in 2009 the budget deficit will have to be something around $90 billion more than is currently projected (and reflected in the IMF growth forecasts).

Given that the estimated $50 billion deficit is sending the commentators into apoplexy one has to wonder whether any of them woould survive the budget deficit that would actually be required to make a responsible intervention into the economy.

But if the Government wants to eat into the rise in unemployment (and underpin more overall hours of work in the economy) then the budget deficit will have to rise considerably above a ratio of 5 per cent of GDP.

Estimating how far above is what the policy debate should be focused on because it will force our politicians to actually articulate what they are choosing the unemployment rate to be. They should be forced to discuss this question and therefore articulate their conception of the output gap – rather than getting sidelined by irrelevant issues about the size of the nominal deficit outcome.

My bet is that the Government will not be able to demonstrate the leadership necessary to make this intervention and the economy will muddle on for some years in states of insufficient GDP and employment growth. And you know what that means! Persistently high rates of unemployment; rising long-term unemployment; rising underemployment; skills atrophy; institutionalised intergenerational disadvantages (kids growing up in jobless households) and all the rest of the filthy business that has been wrought on us by the stultified neo-liberal thinking.

There have been scare journalism in the last days suggesting that this will reduce the nation’s ratings according to the corrupt system of ratings and will push up interest rates. I will write a separate blog about this presently.

Saturday Quiz

Tomorrow a billy blog quiz will be available for your consideration.

This Post Has 0 Comments