I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

The aftermath of recessions

In Paul Krugman’s New York Times Op Ed (January 2, 2011) – Deep Hole Economics we are advised not to get carried away with the signs that the US economy is at last showing signs of consistent growth. I discussed the positive movements in the US jobless claims data in this blog – The year is nearly done … but spending still equals income – last week. Krugman’s point is that while growth is good, the US economy has a huge aftermath (high unemployment) to deal with even once growth returns. The political imperative therefore is to ensure that growth is maximised and not to withdraw fiscal support as soon as the “green shoots” bob up. It is a point that most commentators are ignoring. So can we make sense of this caution?

Krugman said:

If there’s one piece of economic wisdom I hope people will grasp this year, it’s this: Even though we may finally have stopped digging, we’re still near the bottom of a very deep hole.

Recessions impact on a number of economic aggregates in addition to the most visible impact – the rise in unemployment. The great American economist Arthur Okun coined the term “The Tip of the Iceberg” and I borrowed that for the title of a book I co-authored in 2001. The point is that the costs of recession and the resulting persistent unemployment extend well beyond the loss of jobs. Productivity is lower, participation rates are lower, the quality of work suffers and real wages typically fall.

Within this context, Okun outlined his upgrading hypothesis (in the 1960s and 1970s) and the related high-pressure economy model, which provided a coherent rationale for Keynesian demand-stimulus policy positions. Two references are Okun, A.M. (1973) ‘Upward Mobility in a High-Pressure Economy’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1: 207-252 and Okun, A.M. (1983) Economics for Policymaking, Cambridge, MIT Press.

Okun (1983: 171) believed that:

… unemployment was merely the tip of the iceberg that forms in a cold economy. The difference between unemployment rates of 5 percent and 4 percent extends far beyond the creation of jobs for 1 percent of the labor force. The submerged part of the iceberg includes (a) additional jobs for people who do not actively seek work in a slack labor market but nonetheless take jobs when they become available; (b) a longer workweek reflecting less part-time and more overtime employment; and (c) extra productivity – more output per man-hour – from fuller and more efficient use of labor and capital.

The positive side of this thinking is that disadvantaged groups in the economy were considered to achieve upward mobility as a result of higher economic activity. The saying that was attached to this line of reasoning was “all boats (large or small) rise on the high tide”.

Okun’s (1973) results are summarised as follows:

- The most cyclically sensitive industries have large employment gaps, and were dominated by prime-age males, offered high-paying jobs, offered other remuneration characteristics (fringes) which encouraged long-term attachments between employers and employees, and displayed above-average output per person hour.

- In demographic terms, when the employment gap is closed in aggregate, prime-age males exit low-paying industries and take jobs in other higher paying sectors and their jobs are taken mainly by young people.

- In the advantaged industries, adult males gain large numbers of jobs but less than would occur if the demographic composition of industry employment remained unchanged following the gap closure. As a consequence, other demographic groups enter these ‘good’ jobs.

- The demographic composition of industry employment is cyclically sensitive. The shift effects are in total estimated (in 1970) to be of the same magnitude as the scale effects (the proportional increases in employment across demographic groups assuming constant shares). This indicates that a large number of labour market changes (the shifts) are generally of the ladder climbing type within demographic groups from low-pay to higher-pay industries.

The evidence is that when the economy is maintained at high levels of employment, workers in low paying sectors (or occupations) also receive income boosts because employers seeking to meet their strong labour demand offer employment and training opportunities to the most disadvantaged in the population. If the economy falters, these groups are the most severely hit in terms of lost income opportunities.

Upgrading also focuses on the mapping of different demographic groups into good and bad jobs. The groups who experience the greatest relative employment gains when economic activity is high are those who are stuck in the secondary labour market, typically, teenagers and women.

While these groups are proportionately favoured by the employment growth, the industries with the largest relative employment growth are typically high-wage and high-productivity and employ mostly prime-age males. Expansion is therefore equated with ladder climbing whereby males in low-pay jobs (as a result of downgrading in the recession) climb into better jobs and make space for disadvantaged workers to resume employment in their usual sectors. In addition, favourable share effects in predominantly male industries provide better jobs for teenagers and women.

So there are many benefits from growth which spread out across rising participation, rising wages, rising hours of work, rising employment and falling unemployment.

But the downside is that the iceberg takes a long time to melt if (a) it is large; and (b) if the recovery is not robust enough. Recovery alone is not sufficient. Real GDP growth has to be consistently strong for some years before the iceberg melts and the upgrading bonuses accrue.

That is Krugman’s point.

Further, when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) met on December 14, 2010 to decide monetary policy settings in the US they issued their usual statement, which at one point said:

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in November confirms that the economic recovery is continuing, though at a rate that has been insufficient to bring down unemployment.

So what do they actually mean?

In this context, the ILO released a report – Recovery and growth with decent work – published June 18, 2010, which urges the G-20 to place “employment and social protection at the centre of recovery policies”. The ILO note that:

… we must not forget that for many working women and men, and for many enterprises in the real economy, recovery has not yet started … Although job growth has reappeared, global unemployment is still at record levels. This is just the tip of the iceberg of discouraged jobseekers, involuntary temporary and part-time workers, informal employment, pay cuts and benefit reductions. There is still much suffering in many countries. Insecurity and uncertainty abound both for enterprises and for workers.

This is borne out by the persistently high unemployment that will remain for years to come not only impoverishing those directly involved but also setting up the conditions for intergenerational disadvantage as the children who grow up in jobless homes have been shown by the extant research to inherit the disadvantages of their parents. They suffer poor work histories and transit between one poorly paid job after another interspersed with lengthy periods of unemployment.

Krugman thus cautions against too much optimism and urges policy makers not to “look at a few favorable economic indicators … [and] … decide that they no longer need to promote recovery, and take steps that send us sliding right back to the bottom.”

I also think that is a major danger quite apart from the on-going political haranguing coming from the deficit-terrorists.

Krugman rightly says that while real GDP is showing growth it is:

Jobs, not G.D.P. numbers, are what matter to American families. And when you start from an unemployment rate of almost 10 percent, the arithmetic of job creation – the amount of growth you need to get back to a tolerable jobs picture – is daunting.

What is this arithmetic? Well it relates to Okun’s work referred to earlier. He developed the so-called Okun’s Law arithmetic to estimate the deficiency in GDP growth which leads to rising unemployment rates. Okun’s Law (it was in fact a statistically estimated relationship with stochastic variation) is the relationship that links the percentage deviation in real GDP growth from potential to the percentage change in the unemployment rate.

The algebra involved in the conceptualisation of this “law” can be manipulated to come up with a “rule of thumb” which is a way of making guesses about the evolution of the unemployment rate based on real output forecasts.

What is a rule of thumb? It is not a rigid exact relationship. There are no such relationships in social sciences. It is rather a recognition that labour market and product market aggregates are intrinsically linked by construction and behaviour and over time allow us to make guesses about the future of one variable based on the evolution (hypothesised) of other variables.

Here is a simple explanation of this rule of thumb. We can relate the major output and labour-force aggregates to form expectations about changes in the aggregate unemployment rate based on output growth rates. A series of accounting identities underpins Okun’s Law and helps us, in part, to understand why unemployment rates have risen. Take the following output accounting statement (which is true by definition and not a matter of opinion or conjecture):

(1) Y = LP*(1-UR)LH

where Y is real Gross Domestic Product, LP is labour productivity in persons (that is, real output per unit of labour), H is the average number of hours worked per period, UR is the aggregate unemployment rate, and L is the labour-force. So (1-UR) is the employment rate, by definition.

Equation (1) just tells us the obvious – that total output produced in a period is equal to total labour input [(1-UR)LH] times the amount of output each unit of labour input produces (LP) .

Using some simple calculus you can convert Equation (1) into an approximate dynamic equation expressing percentage growth rates, which in turn, provides a simple benchmark to estimate, for given labour-force and labour productivity growth rates, the increase in output required to achieve a desired unemployment rate.

Accordingly, with small letters indicating percentage growth rates and assuming that the hours worked is more or less constant, we get:

(2) y = lp + (1 – ur) + lf

Re-arranging Equation (2) to express it in a way that allows us to achieve our aim (re-arranging just means taking and adding things to both sides of the equation):

(3) ur = 1 + lp + lf – y

Equation (3) provides the approximate rule of thumb that if the unemployment rate is to remain constant, the rate of real output growth must equal the rate of growth in the labour-force plus the growth rate in labour productivity.

Remember that labour productivity growth reduces the need for labour for a given real GDP growth rate while labour force growth adds workers that have to be accommodated for by the real GDP growth (for a given productivity growth rate).

It is an approximate relationship because cyclical movements in labour productivity (changes in hoarding) and the labour-force participation rates can modify the relationships in the short-run. But it should provide reasonable estimates of what will happen once all the cyclically-sensitive components of the economy return to more usual values.

For example, labour participation rates in the US prior to the downturn were around 66 per cent whereas over the 11 months in 2010 for which data is currently available the average was 64.6 per cent. The average over the entire period 2000-2010 was 66 per cent. So in the short-term as growth strengthens we will expect the labour force participation rate to rise again back towards 66 per cent or thereabouts.

In other words, the labour force growth in the short-run will be more brisk than it will be once growth is sustained which will tend to mean our rule of thumb will overestimate the decline in the unemployment rate in the short-term although over a longer period the rule of thumb will be more accurate.

Krugman clearly is considering this rule of thumb. He says:

First of all, we have to grow around 2.5 percent a year just to keep up with rising productivity and population, and hence keep unemployment from rising. That’s why the past year and a half was technically a recovery but felt like a recession: G.D.P. was growing, but not fast enough to bring unemployment down.

Growth at a rate above 2.5 percent will bring unemployment down over time … Now do the math. Suppose that the U.S. economy were to grow at 4 percent a year, starting now and continuing for the next several years. Most people would regard this as excellent performance, even as an economic boom; it’s certainly higher than almost all the forecasts I’ve seen.

Yet the math says that even with that kind of growth the unemployment rate would be close to 9 percent at the end of this year, and still above 8 percent at the end of 2012. We wouldn’t get to anything resembling full employment until late in Sarah Palin’s first presidential term.

Now do the math! Okay, I decided to look at the data to make some projections. Here is what I came up with.

I used the average labour force growth from 2002 to 2007 being the recent periods that we less affected by recovery (early 2000s) or downturn (2008-2010). The average labour force growth rate was 1.05 per cent per annum.

You can get productivity growth data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. They supply annual growth rates for Total Manufacturing Output per Hour of All Persons; Business Output perHour of All Persons; and Nonfarm Business Output per hour of all persons.

So what if we take a low productivity growth scenario (1.5 per cent per annum) and a high productivity growth scenario (2.5 per cent per annum) to see how sensitive the projections might be. I computed the historical averages over the 2002-2007 period of real GDP per person to check whether these rates were realistic. The answer is that the actual productivity growth rate is likely to be somewhere within the high-low range.

I also took two real GDP growth rates: (a) the four per cent that Krugman mentions; and (b) the actual real GDP trend growth rate trend taken from data provided by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis – 2.6 per cent per annum. Once again I used the average rate prevailing between 2002 to 2007 to reduce the cyclical-sensitivity somewhat.

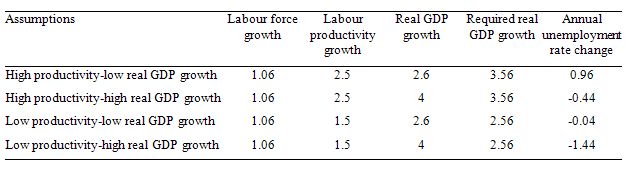

The following Table sets out the assumptions I used for these “rule of thumb” simulations.

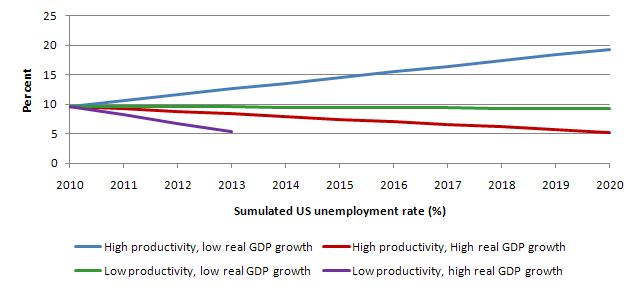

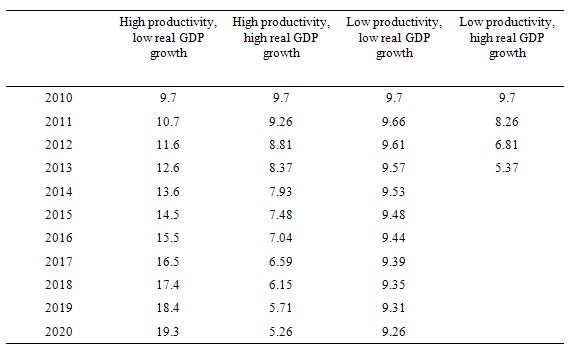

The following graph shows the simulations (aka mindless application of the rule of thumb) from the starting point of an average unemployment rate in 2010 (to November) of 9.7 per cent out to 2020. I stopped the most optimistic scenario after 3 years because it would be associated with the national unemployment falling below the average over the last decade. I do not think this scenario is realistic at all given past data trends.

The following Table shows the simulated values that are graphed above for those who prefer numbers to graphs.

The most realistic assumptions are low productivity growth and low real GDP growth (the green line in the graph or column three in the table). Remember the low real GDP growth assumption is the average growth between 2003 and 2007 so is based on actual data. I do not expect the US economy to grow at 4 per cent for very long.

So under that scenario the unemployment rate hovers around 9 per cent for the next decade.

That is Krugman’s concern.

It is possible that you could get a strong recovery in the next year or so (say the high real GDP growth assumption for 2010-2012) with growth then settling back to historical averages (low real GDP growth). Under this scenario, the unemployment rate would be 6.46 per cent by 2020. So after a decade, the rate would still not be below the average of the previous decade.

The estimation of the required GDP growth rate is clearly dependent by construction on the labour productivity growth estimates. In recent years, labour productivity growth has been lower than in the past because of the dumbing down of the labour market – the dominance of service sector employment and the dominance of casualised work within that compositional shift.

As a result, the lower is the labour productivity growth rate the easier it will be for the US economy to meet the required real GDP growth rate. However, in terms of growth in material standards of living, it is labour productivity growth that matters. So the higher employment growth that might accompany the low productivity growth rate scenario will also be associated with lower growth (if any) in real wages.

What the updgrading hypothesis tells us is that there is an imperative in restoring strong real GDP growth and high productivity growth. This not only reduces the unemployment rate more quickly (although the higher the productivity growth the less the real GDP growth will eat into the pool of unemployed) but it also provides support for faster real wages growth.

Krugman says of all this:

Seriously, what we’re looking at over the next few years, even with pretty good growth, are unemployment rates that not long ago would have been considered catastrophic – because they are. Behind those dry statistics lies a vast landscape of suffering and broken dreams. And the arithmetic says that the suffering will continue as far as the eye can see.

That is the aftermath of the recession and requires a long-term commitment by the government to ensure that job creation is strong enough earlier enough to absorb the unemployed.

But of-course, high rates of real GDP growth are not necessarily desirable. First, the inflation risk rises. Second, from an environmental perspective we have to ensure that growth is sustainable in terms of the natural resource base. Green growth might not be high growth. The bias has to be towards slower real GDP growth.

So where does that leave us? Krugman also asks “what can be done to accelerate this all-too-slow process of healing?” and says:

A rational political system would long since have created a 21st-century version of the Works Progress Administration – we’d be putting the unemployed to work doing what needs to be done, repairing and improving our fraying infrastructure. In the political system we have, however, Senator-elect Kelly Ayotte, delivering the Republican weekly address on New Year’s Day, declared that “Job one is to stop wasteful Washington spending.”

Given the green growth constraint but the need to get as many jobs per growth percent, the best solution in my view is for the US government to immediately introduce a Job Guarantee.

Please read the blogs that the following search string – Job Guarantee – provides.

A Job Guarantee would break into the rule of thumb in a significant way by ensuring that every dollar that the government spends is contributing directly to wages.

Conclusion

It is clear that the US polity is moving in exactly the wrong direction than what is required and seem to be in denial about the realities of the situation (the aftermath) that they are responsible to improve.

The way I read the new congress is that they will introduce policies that could actually put the brakes on the modest growth that I expect is emerging at present. Then the unemployment rate rises and the hardship mounts.

It would be a truly mindless strategy but that seems to be the nature of American politics at present.

That is enough for today!

“But of-course, high rates of real GDP growth are not necessarily desirable. First, the inflation risk rises. Second, from an environmental perspective we have to ensure that growth is sustainable in terms of the natural resource base. Green growth might not be high growth. The bias has to be towards slower real GDP growth.”

“Given the green growth constraint but the need to get as many jobs per growth percent, the best solution in my view is for the US government to immediately introduce a Job Guarantee.”

What about a retirement guarantee? If there are more retirees, will that tighten up the labor market without higher real GDP growth?

With your sumulated (simulated???) US unemployment rate chart and under the high productivity/low real GDP growth scenario, should some to most of the productivity gains go into the retirement market so the labor market does not become oversupplied?

“As a result, the lower is the labour productivity growth rate the easier it will be for the US economy to meet the required real GDP growth rate.”

Nope. If real GDP growth is high enough and labour productivity growth is low enough to tighten up the labor market so that most workers can attempt to get real wages into positive terms, the fed will raise rates (and/or get congress to stop producing enough gov’t debt) to stop it to benefit their rich friends and banking buddies.

It seems to me that we have a paradox growing. We need innovation so that we can produce more stuff more efficiently with less input, unfortunately that will currently lead to less labour being used and therefore less income to purchase the stuff.

Surely at some point we have going to have to break the link between income and ‘work’?

Thank you, Bill. This is an important point to get across given that more and more economists are instead viewing current events through the lens of a rising “natural rate of unemployment.”

Surely at some point we have going to have to break the link between income and ‘work’?

It simply the inertia of the idea that people “must” work in order to deserve. Purely ideological. See, for example, Robert H. Nelson’s Economics as Religion for an investigation of this kind of inertia that gets transferred across time. I like his encapsulation of this transfer of theology to economics as “Calvinism without God.” And, of course, “the invisible hand” is the shadow of God.

The basis of the market system is price. Prices ration distribution, and since ability to pay is based on income, labor is a key factor. However, in capitalism, labor is a commodity, the wage being the price of a resource along with other resources.

The base price of labor, “the wage,” is the subsistence wage. Everything extra is surplus. The game of capitalism is to direct as much of the surplus as possible to capital. Here industrial capital and finance capital view with each other for the bulk of the surplus. Recently, this led industrial capital to compete with finance capital directly through financial arms such as GMAC. The inordinate rise of finance, which creates debt, relative to production led to the GFC. But even without this, for decades gains in increases in productivity have been allocated to productive capital instead of being shared with labor. This trend is accelerating in a “race to the bottom” due to global labor arbitrage. As debt goes bad, the ruling elite in the various countries are forcing government to take the bad debt on their balance sheets through their political influence.

This is all pure ideology. It is based on assumptions that become fixed as rules of the game aka norms.

In the spirit of disclosure, since summer jobs during high school, I have never had a “job.” Yes, it is possible to work gainfully without having “a job.” Lots of people do it.

With respect to green growth:

The US could employ many millions of people providing daycare, elder care, health care, intercity and urban public transit, etc. It is one of the most under-serviced countries of the developed world with respect to such basic services. The provision of these services is green in the sense they do not imply increased pollution, urban sprawl or other negatives in and of themselves. The jobs are highly labour intensive and so low productivity, but they would increase the non-material standard of living tremendously.

The same applies to many other countries but to a lesser degree.

Increased employment in these areas would increase aggregate demand and the likelihood of environmental negatives so appropriate regulation would be required to prevent that.

This is all quite doable but requires political mobilisation, something that is often difficult to do these days. It seems only the most retrograde and confused elements of society are able to organise effectively in the US (see among other articles by Chris Hedges: http://www.truthdig.com/report/page2/the_left_has_nowhere_to_go_20110102/). In some other countries workers and students appear to be able to mobilise but mainly in defensive actions.

I think that we also have to recognize that there is a not-so-hidden agenda at work to divert more of the surplus (value in excess of production cost) that is produced toward capital by changing tax policy, cutting social spending, suppressing wages and benefits, and increasing generally increasing rents.

The unemployment figures are not reflective of the socio-economic reality, for example, owing to the tendency, which is really a tactic in the above strategy, to replace full time jobs carrying benefits with part time jobs without benefits. While wages have been flat for decades, employee compensation has remained constant due to increasing benefits, especially health care. Thus, the job that shows up in the data as a job created is not really a job in the sense implied.

Similarly, a lot of the increase in employment due to productive investment resulting from rescue and stimulus, which has increased the bottom line of multinationals based in the US, is due to outsourcing.

These folks are rolling out every trick in the books and some not in the books. So while the numbers may be improving, the green shoots may be weeds as far as most people are concerned.

Tom Hickey said: “The base price of labor, “the wage,” is the subsistence wage. Everything extra is surplus. The game of capitalism is to direct as much of the surplus as possible to capital.”

And is this because almost all economists make the mistake of assuming real aggregate demand is unlimited, leading them to believe the faster aggregate supply can grow with or without debt the faster the economy will grow?

10 Signs That Our Nation [US] Is Becoming Poorer

Putting some numbers on the deteriorating employment and compensation situation.

Fed Up, neoliberal economists do not recognize a number of things – surplus, economic rent, public goods, the existence of society as a social system, the relation of economics to biological and social science, etc. They create models based on made up assumptions that fitted to produce the desired ideological outcome. They are doing theology rather than science.

Here is a worthwhile read from Foreign Policy. More examples from foreign policy than economics but still relevant to the discussion here.

Where Do Bad Ideas Come From? And why don’t they go away?

TEN THESES ON NEW DEVELOPMENTALISM

Several PK’ersm e.g, Paul Davidson and MMT’ers, e.g., Randy Wray, are original subscribers to this.

Neil Wilson: “It seems to me that we have a paradox growing. We need innovation so that we can produce more stuff more efficiently with less input, unfortunately that will currently lead to less labour being used and therefore less income to purchase the stuff.

“Surely at some point we have going to have to break the link between income and ‘work’?”

Didn’t Henry Ford address that problem rather successfully without breaking that link? 🙂

We can create jobs that put almost no strain on the environment.

For example, we could hire people to walk around in public places, smile at and be polite to everyone they meet. Over the long term, this would improve the health and well-being of the citizenry.

Min said: “Neil Wilson: “It seems to me that we have a paradox growing. We need innovation so that we can produce more stuff more efficiently with less input, unfortunately that will currently lead to less labour being used and therefore less income to purchase the stuff.

“Surely at some point we have going to have to break the link between income and ‘work’?”

Didn’t Henry Ford address that problem rather successfully without breaking that link?”

If wages are increased and people have enough stuff, will they take the increased real earnings and save/earn a return on their savings so they can retire earlier?

Keith: “could employ many millions of people providing daycare, elder care, health care, intercity and urban public transit, etc. It is one of the most under-serviced countries of the developed world with respect to such basic services.”

I absolutely agree. Not just in the US either. The issue is the workers in it are considerably underpaid for what they do and I imagine it would have a high level of stress and a high emotional toll in doing such work.

Whilst I’m extremely thankful for those in the ‘care’ industry, I have no idea how they do it.

Keith: could employ many millions of people providing daycare, elder care, health care, intercity and urban public transit, etc. It is one of the most under-serviced countries of the developed world with respect to such basic services.

Guaranteed that progressives would howl that government would be creating a servant and serf class with a JG. Whats’ the response?

“I think that we also have to recognize that there is a not-so-hidden agenda at work to divert more of the surplus (value in excess of production cost) that is produced toward capital by changing tax policy, cutting social spending, suppressing wages and benefits, and increasing generally increasing rents.”

It’s been happening for a long time. And now Republicans want to slash $100 billion from the budget, and they’re targeting programs that benefit the most vulnerable in our society.

I’m advising my children to emmigrate to a civilized country.

Tom Hickey mentioned the subsistance wage. Seems to me we could stimulate the economy while maintaining productivity or even increasing it by freezing wage increases for anyone being paid 3 times the subsistance wage and giving it to anyone who is paid less than 2 times subsistance wage. That should boost consumption at the cost of reduced savings.

It will also correct the compensation balance. I believe the guy who cleans the toilets in our office buildings is making a bigger contribution to our lives than mosts forcasters at the banks. To test that theroy just stop paying the cleaners in your office building for a month and see want happens to the toilets. Now do the same with 20 forcasters from the banks and then compare the results. The cleaners contribution to productivity should come out in front. No one will even notice that the forcasters didnt turn up to work for a month. Therefore the cleaners are grossly under paid. Eventually the cleaning class will get fed up with wages that dont keep pace with inflation and simply take what the bankers have. Inevitable in the long run.

bill, I hope you don’t mind if I add this for reference.

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/A-boom-in-corporate-profits-a-apf-3135711604.html

“A boom in corporate profits, a bust in jobs, wages

Economic disconnect: Corporate profits surge while jobs and wages remain at recession levels

Friday July 22, 2011, 6:36 pm EDT

WASHINGTON (AP) — Strong second-quarter earnings from McDonald’s, General Electric and Caterpillar on Friday are just the latest proof that booming profits have allowed Corporate America to leave the Great Recession far behind.

But millions of ordinary Americans are stranded in a labor market that looks like it’s still in recession. Unemployment is stuck at 9.2 percent, two years into what economists call a recovery. Job growth has been slow and wages stagnant.

“I’ve never seen labor markets this weak in 35 years of research,” says Andrew Sum, director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University.

Wages and salaries accounted for just 1 percent of economic growth in the first 18 months after economists declared that the recession had ended in June 2009, according to Sum and other Northeastern researchers.

In the same period after the 2001 recession, wages and salaries accounted for 15 percent. They were 50 percent after the 1991-92 recession and 25 percent after the 1981-82 recession.

Corporate profits, by contrast, accounted for an unprecedented 88 percent of economic growth during those first 18 months. That’s compared with 53 percent after the 2001 recession, nothing after the 1991-92 recession and 28 percent after the 1981-82 recession.

What’s behind the disconnect between strong corporate profits and a weak labor market? Several factors:

— U.S. corporations are expanding overseas, not so much at home. McDonalds and Caterpillar said overseas sales growth outperformed the U.S. in the April-June quarter. U.S.-based multinational companies have been focused overseas for years: In the 2000s, they added 2.4 million jobs in foreign countries and cut 2.9 million jobs in the United States, according to the Commerce Department.

— Back in the U.S., companies are squeezing more productivity out of staffs thinned by layoffs during the Great Recession. They don’t need to hire. And they don’t need to be generous with pay raises; they know their employees have nowhere else to go.

— Companies remain reluctant to spend the $1.9 trillion in cash they’ve accumulated, especially in the United States, which would create jobs. They’re unconvinced that consumers are ready to spend again with the vigor they showed before the recession, and they are worried about uncertainty in U.S. government policies.

“Lack of clarity on a U.S. deficit-reduction plan, trade policy, regulation, much needed tax reform and the absence of a long-term plan to improve the country’s deteriorating infrastructure do not create an environment that provides our customers with the confidence to invest,” Caterpillar CEO Doug Oberhelman said.

Caterpillar said second-quarter earnings shot up 44 percent to $1 billion– though that still disappointed Wall Street. General Electric’s second-quarter earnings were up 21 percent to $3.8 billion. And McDonald’s quarterly earnings increased 15 percent to $1.4 billion.

Still, the U.S. economy is missing the engines that usually drive it out of a recession.

Carl Van Horn, director of the Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, says the housing market would normally revive in the early stages of an economic recovery, driving demand for building materials, furnishings and appliances — creating jobs. But that isn’t happening this time.

And policymakers in Washington have chosen to focus on cutting federal spending to reduce huge federal deficits instead of spending money on programs to create jobs: “If we want the recovery to strengthen, we can’t be doing that,” says Chad Stone, chief economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a research group that focuses on how government programs affect the poor and middle class.

For now, corporations aren’t eager to hire or hand out decent raises until they see consumers spending again. And consumers, still paying down the debts they ran up before the recession, can’t spend freely until they’re comfortable with their paychecks and secure in their jobs.

Said Van Horn: “I don’t think there’s an easy way out.””