I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The real World Cup

Regular readers will by now know I am not a soccer fan. And my national team (now locally known as the shockeroos) seemed like rank amateurs the other day against the might of Deutschers. The German coach described the game as “a good warm-up”. Reality check! But of-course, there is a competition going on in South Africa that a lot of people are interested in. So I have been following it myself. I am of-course referring to the The First Poor People’s World Cup which is currently underway in South Africa. This event involves 36 teams from 40 different communities coming together on a shoe-string budget to play soccer. In cost benefit terms it will add a lot more value to South Africa than the other less important competition that is being simultaneously run in South Africa.

We learn that:

On the 13th of June 2010, the Poor People’s World Cup successfully kicked-off their first day of matches at the Avendale soccer fields, next to Athlone stadium in Cape Town. Early in the morning, the first minibuses with soccer teams arrived from all over Cape Town to play their first games in this Poor People’s tournament. Everybody was excited and the atmosphere was amazing, considering the bad weather forecasts.

The motivation of the event is to have an open community-based event.

The organisers explained:

… this tournament is not only for the soccer teams, but also for the whole community and for the people who struggle everyday against water and electricity cut-offs and against evictions from their homes and working places. The message during the meeting was clear: while the poor people in Cape Town and in South Africa as a whole are suffering, the rich are enjoying themselves in the expensive stadiums at the expenses of the poor.

The “traders and communities” who were trampled by the “FIFA related urban renewal projects and by the implemented by-laws” are included in this event. As you will read, the developments made by the South African government in preparation for the FIFA event led to mass evictions and considerable urban dislocation. The poor were kicked out of their dingy homes (and made homeless) to make way for a new stadium or something.

I am particularly interested in South Africa, having worked there recently and having a good understanding of its economy. So I have been following the preparation developments and the government outlays closely as the unreal World Cup has approached. My conclusion: the poor will not benefit from this huge waste of resources. And … this conclusion has nothing to do with my opinion of soccer. That only extends to boredom rather than scandal.

Unemployment and poverty in South Africa

At least 25 per cent of South Africans of working age are unemployed. If you broaden the measure you might reach upwards of 60 per cent (underemployment, discouraged etc). More than 50 per cent of South Africans live below the poverty line (and that line is set very low indeed).

The link between poverty and its major cause – unemployment – is undeniable. But in noting this obvious link I always emphasise that these two twin evils are both political problems. There is nothing intrinsic to a modern monetary economy such as South Africa that makes either poverty or unemployment inevitable.

The resolution of these twin evils overwhelmingly reflects the choices made within the political system and while the problems are significant in South Africa they are not insurmountable if an appropriate policy framework is put in place.

In fact, South Africa would seem to have the preconditions that would make the task of achieving full employment and poverty alleviation more easy than other nations. It has no shortage of space and is resource-rich in both natural and human terms. It has also developed the highest quality education, health care and personal care support systems that are available anywhere in the World but these are still beyond the grasp of the majority despite transition.

It is no surprise that these resources were applied and distributed highly unequally under the apartheid system. The logic of that system was, in part, to deny the rights of the vast majority for the benefit of the few. However, despite abandoning the formal apartheid system as a legal framework to define rights, South Africa does not appear to have abandoned the underlying economic organisation and structure that underpinned and perpetuated it.

In fact, the same system that generated economic inequalities under apartheid continues to deny the majority of South Africans access to the production and distribution systems.

The continuation of this economic organisation and the strong policy support for it from the national government (for example, pursuing budget surpluses under the neo-liberal mandate) indicates that the dramatic inequalities that continue in democratic South Africa today are undeniably a result of political choice.

In saying that, I also recognise that the transition to democracy placed significant pressures on the political machinery available in South Africa. This machinery had not evolved under apartheid to deliver social democratic outcomes.

Further, in making the transition towards the adoption of social democratic ideals, the South African government has received poor advice from external governments and international institutions and has been under incredible pressure to confirm to the “world economic order” which is typified by the neo-liberal agendas set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

That agenda makes the elimination of poverty and unemployment difficult to accomplish because it places the necessary fiscal tools in a straitjacket and does not support redistributive policies that more equably share the wealth generated by a nation economy.

The South African government does have the policy capacity available to it to enable full employment and the significant reduction of poverty. The challenge is for it to identify this capacity and use it to develop the policy structures which will improve employment outcomes for all and reduce the widespread poverty.

None of this is to say that the task is easy. The logistics alone of transforming an apartheid economy into a more equal and inclusive social system are daunting. But the task has to be pursued within the correct economic and social policy framework which has not been particularly forthcoming in democratic South Africa.

The post-apartheid South African administration adopted what the neo-liberal economic understanding of the world and the policy apparatus that is concomitant with that understanding. The most explicit example of this is seen the transition from the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Programme (GEAR).

The RDP was envisaged to be the cornerstone for building a better life of opportunity, freedom and prosperity. It was to be the policy that actualised civil society’s call for equality, redistribution and access. The RDP spoke of poverty alleviation and economic reforms, and provided a broad framework for the socio-economic restructuring of South Africa.

In 1996 RDP was superseded by GEAR. GEAR adopted explicit economic growth strategies that were oriented towards private sector investment and assumed the role of the public sector and government programmes to be minimal. The GEAR strategy pursued fiscal discipline by minimising deficits and maintaining high real interest rates, which paradoxically constrained economic and employment growth.

The failure of GEAR is never more evident than in the discrepancy between the economic modelling, which predicted that a 6 per cent growth rate would create an average of 270,000 additional jobs annually in the formal sector, and the outcomes, which saw formal sector employment, stagnate and fall.

It is no surprise then that the richness of resources have not been used to benefit the greater population.

Neo-liberal economics emphasises the primacy of the private market place and uses “private costs and benefits” as the basis of resource allocations, largely ignoring the broader and more inclusive concept of “social costs and benefits”.

In the case of South Africa, this translates into the hard to understand combination of a government running fiscal surpluses (prior to the crisis) and more than 60 per cent of the population without adequate housing or income. The surpluses were justified by the erroneous claim that they are fiscally responsible management, a central misnomer of neo-liberal thinking which remains stuck in a time when fixed exchange rates and commodity money was the norm.

In a flexible exchange rate world and where the government maintains sovereignty over its currency, these notions are inapplicable. The application of them results in dysfunctional outcomes which we see in the stark reality of the South African situation.

Throughout the policy literature one reads that unemployment in South Africa is a complex and manifold problem. The construction of unemployment in South Africa as being a “structural problem” dominates the debate with contributions supporting this perspective coming from all sides of the political landscape. Various academic researchers also argue that unemployment is structural.

I have never shared the view that the overwhelming unemployment problem is structural in nature. In a modern monetary economy, the government always has the capacity to create a pool of jobs that would be inclusive of the most disadvantaged workers and be spatially matched to the pattern of economic settlement.

In that sense, to say the unemployment is structural is to assume all jobs have to be created by the dynamics of the private market place and selection and offer of training slots should reflect the prejudices of the private sector employers.

In my work in South Africa on the Expanded Public Works Programme it was clear that when jobs were made available in a region there were always enough workers to be productively engaged. The problem was that the programme did not offer enough jobs because it was budget constrained by the Treasury under IMF dictate.

By any standards, the unemployment problem in South Africa is what economists call a demand deficiency situation rather than a structural problem. This means there is not sufficient demand for labour being generated overall. The South African economy does not produce enough jobs and the labour queue then reflects the distribution of skills with the least skilled in the most disadvantaged position in the face of job scarcity.

There is not a shortage of meaningful job opportunities that could be pursued in South Africa if there was a willingness to fund the employment. The private sector is clearly unable to generate the level of employment commensurate with the willing labour supply. This chronic state is a prima facie justification for a direct public sector job creation.

It is clear from the most cursory examination of the South African labour force data that this is an economy that fails to generate enough jobs not one that generates enough work in areas unsuited to those who are seeking work. That situation is not one of structural unemployment by any definition of the word. The solution to South Africa’s unemployment problem is to generate more work.

Further, it is highly unlikely that the private sector will provide the impetus to solve this problem. It therefore falls back on the South African government to generate the necessary employment via direct job creation.

Democracy in South Africa

With the end of the apartheid system in South Africa in 1994, the new democracy inherited the legacy of the years of economic isolation which had left a mal-functioning economic system incapable of stable positive growth and incapable of generating enough employment to satisfy the willing labour force.

So the country not only faced the social challenges of bringing its population together as a nation, but also faced the daunting economic challenge of improving growth and, significantly, providing for significant redistribution of the growing wealth to reduce the massive inequalities that had been created. The redistribution of wealth and opportunity was a crucial aspect of redefining South Africa as a united nation.

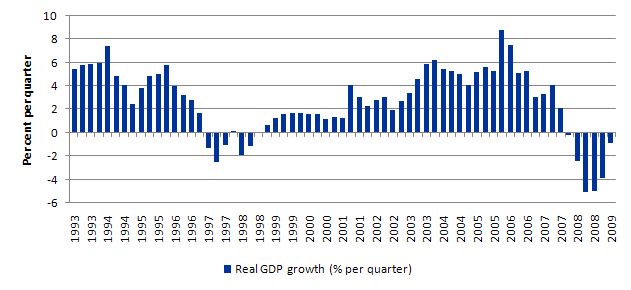

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in real GDP from March 1993 to March 2010, so the entire period of democracy. The data is available from Statistics South Africa.

After more than a decade of democracy, the economy began to enjoy sustained growth riding on the global commodities boom that has benefited many commodity exporting nations. StatsSA data show that real GDP growth was an annualised 6.2 per cent in 2006, 5.25 per cent in 2007, falling to 2.3 per cent in 2008 and plunging to -4.1 per cent in 2009 as the crisis hit.

The growth period constituted the longest period of growth in its history. The outlook after the crisis still looks bleak. The March quarter growth rate was -0.9 per cent. The Treasury estimated that the World Cup would add only 0.5 per cent to GDP growth in 2010, so perhaps not enough to get it out of recession.

Prior to the crisis, as well as enjoying the benefits of the global commodities boom, South Africa’s population growth rate was slowing which means that real per capita income had been rising. This fact stands in contrast to last decades of the apartheid era. Between 1980 and 1990 the population grew by around 56 per cent (24.3 million to 37.9 million). The growth rate slowed to 15.1 per cent over the next decade (see http://populstat.info/Africa/safricag.htm) and StatsSA estimated the population in mid-2007 to be 47.9 million compared to the 2001 Census total of 44.8 million. The population growth rate is now around 1.4 per cent per annum compared to an average of 5.6 per cent in the 1980s.

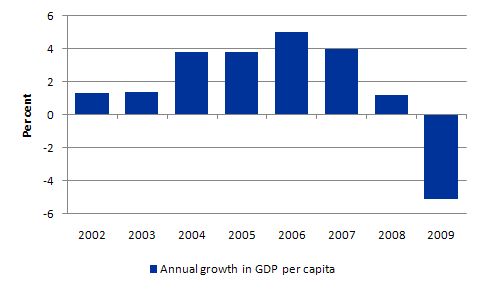

However, the crisis has had a devastating impact on the growth in per capita incomes. The following graph shows the annual growth in real GDP per capita from 2002 to 2009. In 2009, per capita GDP fell by more than 5 per cent wiping off 5 years of growth. The situation will worsen in 2010.

The other striking feature of the democratic era has been the major restructuring of industry that has occurred in South Africa. This is in part a response to the trade liberalisation which helped diversify its export base. South Africa has moved from being predominantly a primary commodity exporter to increasingly exporting elaborately-transformed manufactures which require high-skills and capital intensive production methods.

However despite the positive growth, the South African economy remains highly segmented and the politicians have not seen fit to distribute the wealth it creates to reduce the gross inequities that were inherited from the apartheid era.

In the two-tiered South African economy, advantage and opportunity are largely confined to the first-tier workers who enjoy middle to high incomes by World standards, relatively stable employment, access to skill development and well-defined career paths. The dominant industries in the formal economy are mining, manufacturing, agriculture and the services sector are all sophisticated in terms of technology and organisation. In the second-tier economy these characteristics are absent and low pay and inadequate employment growth predominates.

Furthermore, a significant proportion of the population are almost completely locked out of the economic production and distribution system.

The other aspect of the South African economy which is atypical of a developing nation is that it has a small informal sector and very little home production (subsistence agriculture). As a consequence, most people are dependent on market employment for earnings supplemented with government transfers.

Despite the economic growth, the opportunities being created by the formal sector are not helpful to unskilled workers with little formal education and training nor are the government transfers (either direct or via programmes) sufficient. The result is that unemployment (however defined) and poverty rates are high.

A major problem constraining the social development of the South African economy is the policy framework that the government has adopted since the democratic era began. The commitment by the Transitional Executive Council (TEC), made up of representatives of the NP government, business leaders and the ANC leadership, to the ‘Statement on Economic Policies’, which was signed as an accord with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (who was lending the Government $US850 million in short-term aid), ensured that a neo-liberal macroeconomic future would ensue (see Terreblanche, 2005, who documents these details of the transition phase between the apartheid system and the democratic era).

By acceding to a litany of neo-liberal constraints on macroeconomic policy from the outset (such as tight fiscal policy) it is hard to see how any coherent policy development could have been achieved which addressed the major problems of unemployment and poverty endured by at least the bottom half of the population.

What South Africa needed desperately then, as it does now, is wide-scale job creation, which in itself would generate wealth redistribution. Some commentators would suggest that ‘comprehensive redistribution’ was the key to reducing poverty in South Africa and could be achieved through budget balances with both increased spending and taxation.

However, such an approach is unlikely to reduce unemployment, the principle cause of poverty, if the non-government sector has a positive desire to save.

Given that the private sector has not proven capable of generating enough employment growth to provide the essential opportunities for the most disadvantaged South Africans to participate in the development process, the case for large-scale public sector job creation funded via deficit spending is compelling.

But in signing up to the austerity approach imposed on countries by the unelected and unaccountable world organisations such as the World Bank and the IMF, the South African government initially and voluntarily hamstrung itself from doing anything significant by way of restoring the balance between labour supply and labour demand.

The unwillingness of the new democratic South African Government to use its fiscal capacity (as an issuer of a sovereign currency) to move the country towards full employment was formalised in 1996, when it adopted the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy as its major macroeconomic framework. The GEAR encapsulated the major neo-liberal principles embodied in the Statement and which had been imposed on many developing countries by the IMF and World Bank in the decade prior to that at great cost to the countries in question.

The neo-liberal agenda is based on the erroneous notion that promoting growth in income and wealth for the most advantaged will “trickle down” to the most disadvantaged. The mechanisms via which this trickle down is alleged to occur are difficult to discern. The reality is that the “trickle down” has not occurred

and this failure is common in economies that have relied on the flawed neo-liberal doctrine.

One of the understandings you reach from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is that the doctrinaire approach adopted by the IMF will is never able to deliver widespread benefits to an economy.

The stark realisation of the failed policy framework is reflected in South Africa’s income distribution and the labour market situation. The fact that it has taken a significant escalation in the coverage and level of the social grants system to make a dent in the poverty outcomes is a further testament to the importance of public sector intervention in reducing inequality and improving economic outcomes for the most disadvantaged.

The labour market reality facing the South African government and the persistence of the problem suggests that major new approaches are warranted.

A substantial proportion of the poor population live without the benefits of employment, in “workerless households”, that is, households without employed workers. Life for those in the poorest households indicates that a large portion of the population are clearly living in income poverty. The average household budget for the poorest quintile amounted to 7072 Rands per annum. Over 55 per cent of that income (4040 Rand), is spent on essential food.

After food, a large proportion of housing income is spent on energy consumption. These people live in rural areas in traditional dwellings and in urban areas in informal shack settlements. Service delivery and access to basic infrastructure has been increasing, however black Africans are still 12 times more likely than other population groups to obtain water from sources outside their homes.

Although all of these households receive some income from a variety of sources, such as government social grants or remittances from migrant workers, none of it is from earnings generated by household members. In 2001, there were 14.6 million persons (overall population 49.6 million) in “workerless households” and by 2004, they had increased to 15.7 million.

Within such a context, it is felt that while provision social grants are necessary, and provides over 11.2 million people with an income source annually, strategies to alleviate poverty should be coupled with provision of employment to put the economy on an equity growth path.

The true extent of unemployment is difficult to measure in South Africa as a result of the informal economy but is in the range of 25 to 35 per cent. (Source). There is also massive hidden unemployment. Some credible estimates could place the total labour underutilisation rate above 60 per cent once you factor in underemployment and marginal status.

These results emphasise the urgent need for policy to come to grips with demand deficiency and chronic poverty. Further, opportunities to perform meaningful roles in the labour market exist in the substantial quantities due to service and infrastructure deprivation from the apartheid era and more recent neoliberal government.

In poor communities poor service provision provides a context for the persistence of poverty, with slack in service delivery becoming the burden of women and children. A strategy that works to address both issues would be advantageous.

The labour market reality facing the South African government and the persistence of the problem suggests that major new approaches are warranted.

And now to the unreal World Cup

So how much has the South African government spent on the World Cup and what is the expected gain?

The 2010 Budget Highlights reports that:

The 2010 FIFA World Cup is expected to contribute about 0.5 per cent of GDP growth in 2010. To date, government has spent about R33 billion in preparation for the tournament.

So 33 billion rand for 0.5 per cent growth in 2010.

The Government made major improvements to the Johannesburg airport (which the likes of me think are wonderful) and a new airport in Durban. They built five new stadiums across the country, including one located right in the heart of the tourist drag in Durban. They have invested around R2 billion on protecting visitors from crime and terrorism.

Do you get the impression that none of this will filter down very far? Who is going to use all the stadiums? Answer: they will mostly be white elephants.

Further, in creating these new sporting major disturbances were made to local communities. There were widespread evictions and urban disruption.

You will be advised to explore the War on Want World Cup Home Page.

They have also created an excellent Interactive Map of Capetown where you can “explore in depth the issues facing the city’s residents in the lead-up to the World Cup”.

The following film provides some insights into how the poor have been treated in the lead up to the World Cup.

With 50 per cent of South Africans in dire poverty, how will five new stadiums help?

Given the public outlays on the World Cup, what would the South African government been able to do by way of job creation?

To get an idea we can consult an actual on-going program – The Expanded Public Works Programme which began in 2004.

If you are interested in reading the complete evaluation report on the first five years of the Extended Public Works Program, which I did for the ILO, then this link will take you to the final draft version – Complete draft ILO Report (5.4 mg). The final version was changed a little but not much.

The first five years of operation aimed to create a million jobs. All government departments and state owned enterprises were to create productive employment opportunities by: (a) Ensuring that government-funded infrastructure projects use labour intensive methods; (b) Creating work opportunities in public environmental programmes and social programmes; and (c) Using government procurement to help small enterprise learnership and support programmes.

So the four main sectors involved were:

- Infrastructure: mostly provincial and local infrastructure suitable to the use of labour-intensive methods; roads, water provision, sanitation, schools, parks, sport fields.

- Environmental: Removal of invasive alien vegetation (Working for Water), Fire protection, wetland rehabilitation, greening, coastal cleaning etc.

- Social: Early Childhood Development, Home and Community Based Care.

- Economic: Small Enterprise Development through government procurement.

The EPWP program targetted the unemployed and marginalised workers – unskilled workers not receiving adequate social transfers with some quota positions for youth and workers with disabilities.

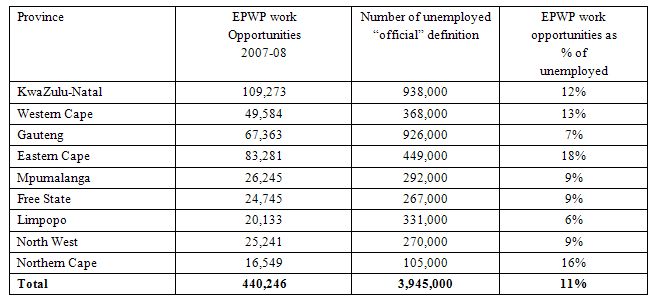

In 2007-08, it created 440,000 jobs and given the fractional nature of the positions (which was one of the shortcomings of the scheme) this translated into 148,000 person-years of employment.

How much had been outlaid to achieve that? In 2007-08, R13.6 billion was spent. The total EPWP expenditure was equivalent to 0.7 per cent of GDP and 2.4 per cent of total government expenditure.

So while the scheme was very successful in reducing poverty among the participants it was too miserly by far. The second five year plan (2009-2014) is more ambitious but still suffering as a result of the failure of the Treasury to release enough funds.

The following table is a snapshot of the EPWP for 2007-08. You can see how inadequate the initial outlays were in terms of dealing with the scale of the problem.

The arithmetic is easy. The South African government has spent R33 billion on the World Cup to date. They could have created more 375,000 full-time jobs for one year directly and even more would flow on via the multipliers. That would have been a much better source of their spending. As it is the World Cup will provide very little to the poor in that country.

The formal evaluations that have been done suggest fairly modest returns to the South African economy (For example). Most of the gains suggested will come from South Africa being a “more attractive investment climate” etc. So fairly speculative gains at this stage especially when FDI has been very apprehensive about South Africa given its very high crime rate.

Conclusion

Don’t get the impression I am anti-sport. I actually am the opposite. But I fail to see the priorities here.

South Africa could have really made a dent in their poverty rate and provided the conditions for the next generation of adults to have skills and hopes by investing the World Cup money in jobs, housing and education.

Then FIFA would have to siphon of their share from another country.

And the real World Cup (the Poor People’s World Cup) would have continued as an inclusive event binding these impoverished communities together.

That is enough for today!

This really highlights how absurd the subsidy of sporting events has become. The pro-subsidy studies are all flawed — they talk about the revenues from tourism as net gains but conveniently forget all of the businesspeople who cancel their plans due to the hassle of the event. The number of foreigners in Beijing during the 2008 Olympics was actually lower than normal for that time of year. And of course, after it all is said and done, the cities are left with white-elephant stadiums and venues which will never be profitable.

Now, not everything built with public funds must be profitable, but, at the very least, they should be public. A park or a museum, for example, might not ‘make money’ but still has a cultural/social value that everyone can enjoy. An empty stadium, however, has no social value — in fact, local governments need to hire security guards to keep the public from getting into the facility!

In the US, the extensive subsidies granted to professional sports teams by local governments is a huge problem. Sports team owners frequently play one city off against another, and threaten to move their teams if the home city fails to build a new stadium. These new stadiums cost cities hundreds of millions of dollars and are designed for exclusive use — so each team gets its own stadium even if there is no seasonal conflict between sports. This trend has been so pervasive that there are hardly any major sporting venues in the US more than 20 years old. Compare that to the average age of an inner-city public school and you can see where the priorities are.

Over the past decade or so, ratings and revenues from television have largely peaked for the major American sports, so owners are relying more and more on stadium revenues to fill the gap. The seating capacity of the new stadiums has actually declined, as more space is reserved for the high-revenue luxury suites. These suites are used primarily by the ultra-rich and corporations, who can actually deduct the cost of the suite from their taxes as a business expense. So all of this public subsidy, which is what is driving player salaries to stratospheric levels, is serving to benefit only the richest of fans.

About 20 years ago, one of the baseball teams in Chicago threatened to move to Sarasota, Florida, if the city did not build the team a new stadium. Even though the team had a 100 year history with the city, and Sarasota is maybe 1/30th the size of Chicago, the city and state caved in and built the team a new stadium. After it was built, the city requested to hold its high school baseball championship game in the new stadium, but the owner refused. This is typical of the mentality of sports franchise owners today.

Although I understand the arguments MMTers are making, you might want to work out a new analogy for the legions of soccer fans out there. Given its proclivity to produce 0-0 and 1-1 ties, soccer fans might actually be worried that the scoreboard operator will run out of points!

“Don’t get the impression I am anti-sport. I actually am the opposite. But I fail to see the priorities here.”

Might have applied just as well to the Olympic games in Greece in 2004.

I’m a soccer fan. Nonetheless I concur with the arguments of Bill. There are legions of papers documenting that no economy gains whatsoever from hosting such events. The “trickle down” argument is an economic zombie idea walking around in various disguises. But the problem isn’t the tournament as such but FIFA and it’s perverse grip on national governments. If Bill wants to add another international villain to IMF and World Bank, FIFA is the first choice!

FIFA is a medieval organisation resembling the worst traits of feudalism. Sepp Blatter the unelected kind handing out national fiefdoms to some unaccountable officials in return for questions not asked. FIFA tries to siphon as much revenue as possible from the beautiful game into it’s pockets for the enrichment of a bureaucratic pseudo-aristocracy. It’s an open secret, that you must bribe some of these mini-dictators to host a world cup tournament.

From a fan perspective we need a soccer Lenin to change things. What is to be done? First we need to abolish the concept of a host nation for world cup tournaments. Instead the world cup should rotate every 4 years from one continent to another and re-use established venues (stadiums). Investment should concentrate on infrastructure beneficial to economies in the absence of any tournament (transport, hospitality, …) This would also put a stop to these nonsensical beauty contests for hosting a world cup.

Next FIFA must be refocused on it’s original purpose. To promote and further soccer worldwide on a basic level. A lot of people think soccer is boring. Fine! Billions of kids don’t think so. This is the game of the poor. You don’t need infrastructure and even no gear to play it. That is the beauty of the game! My father played soccer after the end of WW2 in Vienna with 4 stones as goal posts and a “Fetzenlaberl”, which was fabric stitched together to resemble a ball.

And it’s not only about the kids of the world. It’s about people who associate. Another example: Here in Vienna we’ve a club of blacks who play in the local league. They all have no papers to be here. Thus their club name “FC Sans Papiers”. Once these guys played in the league and had contact to the other teams it was impossible for the police to harass them. Suddenly they had faces for the normal guy on the street and were not just some abstract foreigner in the newspaper. The first time police tried the local players and fans rioted.

FIFA has deep pockets and this should be their original and only task. To further public purpose via promoting soccer in the civil society.

I’ll start watching if they ban the Vuvuzela.

On the same theme:

http://www.whoreallywins.com/