I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Federal minimum wage increase not generous enough

Today, Fair Work Australia, the new body that the incoming Labor government set up to replace the Fair Pay Commission, which the conservatives had crafted to cut real wages, released its first decision. The Minimum Wage Panel of FWA released its first Annual Wage Review under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Fair Work Act) and awarded minimum wage workers an additional $26 per week which amounted to a 4.8 per cent rise. With inflation running around 2.9, the decision provides for a real wage increase barely in line with productivity growth. The decision will apply over from July 1, 2010 to June 30, 2011. The decision does little to restore the real wage losses that low-paid workers have endured over the decade is it sufficient to restore the deterioration of low-pay outcomes relative to average earnings in the economy.

In the Full Decision handed down today, the Fair Work Australia panel said:

Official forecasts indicate that the Australian economy will continue to recover strongly from the GFC-related slowdown in 2009 over the remainder of 2010, and into 2010-11 and 2011-12. Both Treasury and the RBA expect real non-farm GDP to resume growth at levels approaching 4 per cent in 2010-11 and 2011-12, from a level of 2-2½ per cent in 2009-10, with growth driven by private sector consumption and investment and supported by a favourable terms of trade, particularly in 2010-11. The strong growth in output is expected to be reflected in the labour market, with employment growth at or in excess of 2 per cent per annum, average hours returning to more normal levels, increasing participation rates and a reduction in unemployment, notwithstanding an expansion in the labour force … Overall, Australia’s immediate economic outlook is positive, with official forecasts suggesting a resumption of strong growth in economic activity and further steady inroads into unemployment in the context of relatively stable aggregate wages and prices growth.

These are optimistic forecasts and are derived from the Treasury and RBA estimates at present. At present, the economy would have to really accelerate from its current stagnant growth rate to get near these forecasts. Please see my blog – Australia GDP growth flat-lining – where I consider the first quarter National Accounts results, published yesterday for more on the likely outcomes in the period ahead.

It is also interesting that the employers in recent months have been screaming for renewed targetted immigration to address the so-called skills shortage that they claim exists but in this wage hearing they are claiming the economy is not strong enough to pay a 4.8 per cent rise in the wages to the lowest paid workers.

In the Fair Work Australia conclusion their view on this issue is expressed as:

Our view is that the low paid need the highest level of wages that is consistent with all other objectives including low unemployment, low inflation and the viability of business enterprises. At the least, this level of wages should enable a full-time wage earner to attain a standard of living that exceeds contemporary indices of poverty. We are open to evidence that there are particular economic developments that are placing unusual and severe strain on the budgets of the low paid.

While this is a considerable change in emphasis from the previous minimum wage tribunal set up by the last conservative government as an explicit real wage cutting mechanism, the FWA vision falls short of what I find acceptable.

I would not set the minimum wage on capacity to pay grounds. So whether the forecasts are overly optimistic is irrelevant in my view. I would ignore cyclical patterns when considering what the level of the minimum wage should be.

The minimum wage is a statement of how sophisticated you consider your nation to be. Minimum wages define the lowest standard of wage income that you want to tolerate. In any country it should be the lowest wage you consider acceptable for business to operate at. Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

If small businesses or any businesses for that matter consider they do not have the “capacity to pay” that wage, then a sophisticated society will say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in their economy. Firms would have to restructure by investment to raise their productivity levels sufficient to have the capacity to pay or disappear. The outcome is that the economy pushes productivity growth up and increases standards of living.

No worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable standard of living just because low wage-low productivity operator wants to produce in a country.

If you examine the decision you can see what the various submitting parties representing labour and capital requested. The largest demand was from the Women’s Electoral Lobby (WEL) and National Pay Equity Coalition (NPEC) which jointly recommended that the NMW and increase of $49.00 or 9 per cent. As the Fair Work Australia decision says “(t)his would set the weekly rate at $592, a figure relative to average weekly earnings of 48.5 per cent – just short of the pre-AFPC era.”

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) want a rise of $27.00 a week and so will be happy with today’s decision. The main small-medium employers’ federations wanted a rise constrained to $12.62 per week which was consistent with the $12 per week demand from the large employers group. Then you had a ragbag of employers groupings (farmers, retailers. housing industry) all requesting very small rises.

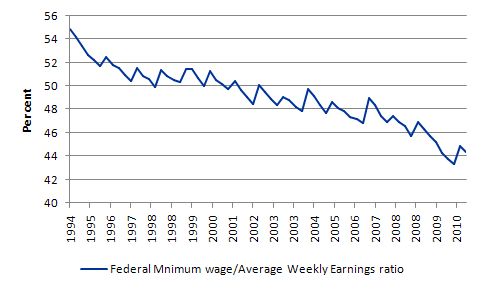

The following graph shows the ratio of the Federal minimum wage to the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings series provided by the ABS (since the third quarter 1994 until the end of 2010). The last three quarters in 2010 are simulated based upon a constant growth in earnings. The new FMW applies from July 1, 2010 so will be constant over the last 2 quarters of 2010.

The logic of the neo-liberal period which encompasses the data sample shown (and then some) was to cut at the bottom of the labour market. Today’s decision continues that trend and forces workers at the bottom of the wage distribution to fall further behind in relative terms.

Staggered wage decisions and real wages

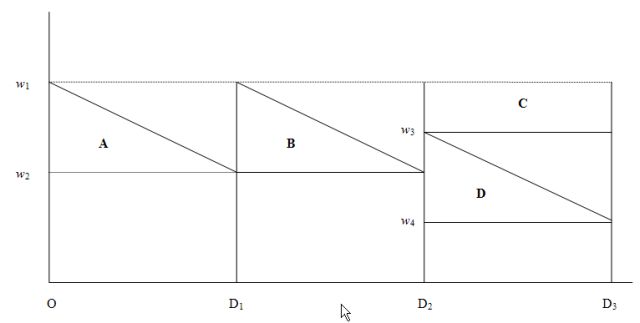

There are also problems with just “maintaining real FMWs” if there are long gaps between adjustments. With inflation going on continuously (more or less), the annual adjustments by the AFPC hand employers huge gains and deprive the workers of real income. The following discussion and diagram explain why.

Assume that at the time of policy implementation, the real FMW wage was wi and there was no inflation. The wage setting authority (in this case the AFPC) manipulates a nominal minimum wage (the $ weekly value) and the real wage equivalent of this nominal wage is found by dividing the nominal wage by the inflation rate. Assume that inflation assumes a positive constant rate at Point 0 onwards.

The nominal wage is the $-value of your weekly wage whereas the real wage equivalent is the quantity of real goods and services that you can purchase with that nominal wage. For a given nominal wage, if prices rise then the real wage equivalent falls because goods and services are becoming more expensive.

The following diagram depicts the real income losses that arise when indexation is not continuous, that is, when the AFPC makes, say, an annual adjustment in the FMW (you may want to click it to get it in a new window so you can print it while you follow the description):

Over the period O-D1 the inflation rate continuously erodes the real value of the nominal wage and immediately before the next indexation decision, the real wage equivalent of the fixed nominal FMW is w2. The real income loss is computed as the area A, which is half the distance (0-D1) times distance (w1-w2).

At point D1 the wage setting authority increases the nominal wage to match the current inflation rate which restores the real wage to w1, but the workers do not recoup the deadweight real income losses equivalent to area A.

The same process occurs in the period between the D1 and the next decision D2, resulting in further real income losses equivalent to area B. These losses are cumulative and are greater: (a) the higher is the inflation rate; (b) the longer is the period between decisions; and (c) the higher is the real interest rate (reflecting the opportunity cost over time).

Clearly, the patterns of real income loss are different if the wage setting authority adopts a decision rule other than full indexation (that is, real wage maintenance). For example, say it decides not to adjust nominal wages fully at the time of its decision (or in fact at the implementation date of its decision) to the current inflation rate then the real income losses increase, other things equal.

So at time D1 the authority decides to discount the real wage (less than full indexation) and increases the nominal wage rate such that the real wage at that point is equal to w3.

Over the next period to D3, the real wage falls to w4 and at the time of the next decision (implementation time D3) the real income losses would be equal to the triangle D (reflecting the inflation effect over the period D2- D3, plus the rectangle C, which reflects the losses arising from the decision to partially index at D2.

Similarly, one can imagine that the adjustment at a particular time might involve a real wage increase (more than full compensation for the current inflation rate) which would then partially offset some of the real income loss borne in the previous period when nominal wages were unadjusted but inflation was positive.

So if you understand the saw tooth pattern of indexation shown here you will see that the triangles A and B represent real losses for the workers between wage setting points even if real wage maintenance is the preferred policy. These losses are worse (areas C and D) if there is only partial adjustment. These losses occur because inflation is a more continuous process than the adjustments in FMW and accrue to the employer. The employers are pocketing these wage losses every day because their revenue is geared to the price rises and they are paying constant nominal wages to the workers.

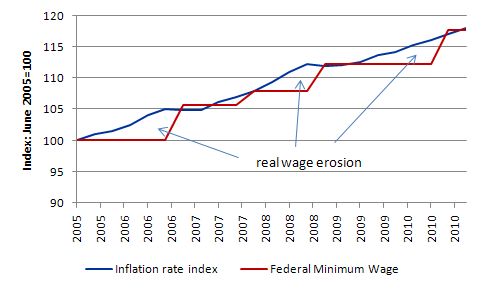

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage since July 2005 extrapolated out to the end of 2010 based on a constant inflation rate. You can see the saw-tooth pattern that the theoretical discussion above describes. Each period that curve is heading downwards the real value of the FMW is being eroded. Each of the peaks represents a formal wage decision by the wage setting tribunal (now Fair Work Australia).

When the workers get the pay rise on July 1, 2010 their real wage equivalent of the nominal FMW will be around what it was five years ago. However, in the meantime, between the wage determination decisions, their purchasing power has been cut significantly – these are permanent losses.

The next graph shows the erosion of the real wage more clearly. The red line is the inflation index and the blue line the nominal Federal Minimum Wage index (June 2005=100).

Minimum wages and employment

Many academic studies have sought to establish the empirical veracity of the neoclassical relationship between unemployment and real wages and to evaluate the effectiveness of active labour market program spending. This has been a particularly European and English obsession. There has been a bevy of research material coming out of the OECD itself, the European Central Bank, various national agencies such as the Centraal Planning Bureau in the Netherlands, in addition to academic studies. The overwhelming conclusion to be drawn from this literature is that there is no conclusion. These various econometric studies, which have constructed their analyses in ways that are most favourable to finding the null that the orthodox line of reasoning (that wage rises destroy jobs) is valid, provide no consensus view as Baker et al (2004) show convincingly.

In the last 10 years, partly in response to the reality that active labour market policies have not solved unemployment and have instead created problems of poverty and urban inequality, some notable shifts in perspectives are evident among those who had wholly supported (and motivated) the orthodox approach which was exemplified in the 1994 OECD Jobs Study.

In the face of the mounting criticism and empirical argument, the OECD began to back away from its hardline Jobs Study position. In the 2004 Employment Outlook, OECD (2004: 81, 165) admitted that “the evidence of the role played by employment protection legislation on aggregate employment and unemployment remains mixed” and that the evidence supporting their Jobs Study view that high real wages cause unemployment “is somewhat fragile.”

The winds of change strengthened in the recent OECD Employment Outlook entitled Boosting Jobs and Incomes, which is based on a comprehensive econometric analysis of employment outcomes across 20 OECD countries between 1983 and 2003. The sample includes those who have adopted the Jobs Study as a policy template and those who have resisted labour market deregulation. The report provides an assessment of the Jobs Study strategy to date and reveals significant shifts in the OECD position. OECD (2006) finds that:

- There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

- The level of the minimum wage has no significant direct impact on unemployment; and

- Highly centralised wage bargaining significantly reduces unemployment.

This latest statement from the OECD confounds those who have relied on its previous work including the Jobs Study, to push through harsh labour market reforms (such as the widespread deregulation in Australia as a consequence of the WorkChoices legislation), retrenched welfare entitlements and attacked the power bases on trade unions. It makes a mockery of the arguments that minimum wage increases will undermine the employment prospects of the least skilled workers.

In their decision today, Fair Work Australia said:

In relation to the relationship between minimum wage rises and employment levels … Although a matter of continuing controversy, many academic studies found that increases in minimum wages have a negative relationship with employment, but there is no consensus about the strength of the relationship. Strong employment growth over the past decade in Australia, in the context of annual increases in minimum wages (other than in 2009) suggests that any impact of moderate minimum wage increases on employment levels is swamped by other factors affecting the demand for labour. We judge that in current economic circumstances, the increase in minimum wages we have decided on will not threaten employment growth.

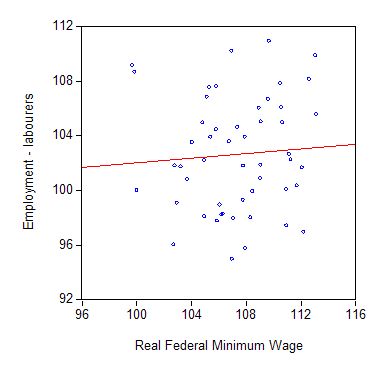

To get some idea of what the data looks like I created a scatter plot of the real federal minimum wage (indexed to 100 at September 1996) (horizontal axis) and the Employment of labourers (vertical axis). The red line is a simple regression which looks pretty flat to me (indicating no relationship). If there is any relationship it is positive which means the higher the minimum wage index the higher is the labourers’ employment index. But when you run the regression in change form (don’t worry about what this means if you don’t know) one concludes there is no relationship.

In a job-rationed economy, supply-side characteristics will always serve to shuffle the queue. Internationally, there is a growing sentiment that paid employment measures must be a part of the employment policy mix.

The lack of consideration given to job creation strategies in the unemployment debate stands as a major oversight. There is growing recognition that programs to promote employability cannot, alone, restore full employment and that the national business cycle is the key determinant of regional employment outcomes. In my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we consider the evidence in considerable detail.

There is also an interesting study from Stephen Machin entitled – Setting minimum wages in the UK: an example of evidence-based policy, which was presented to the Fair Pay Commission’s swansong research forum in Melbourne in 2008.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at University College London, Director of the Centre for the Economics of Education and a Programme Director (of the Skills and Education research programme) at the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, an editor of the Economic Journal (one of the top academic journals), has been a visiting Professor at Harvard University and at MIT. So in mainstream terms he is thoroughly one of the orthodox club.

He examined the impact of the creation of the UK Low Pay Commission, which the Blair Labour Government established to try to remedy some of the worst excesses that the neo-liberal era had delivered to low wage workers. Both sides of politics in the UK from Thatcher onwards were remiss in this regard.

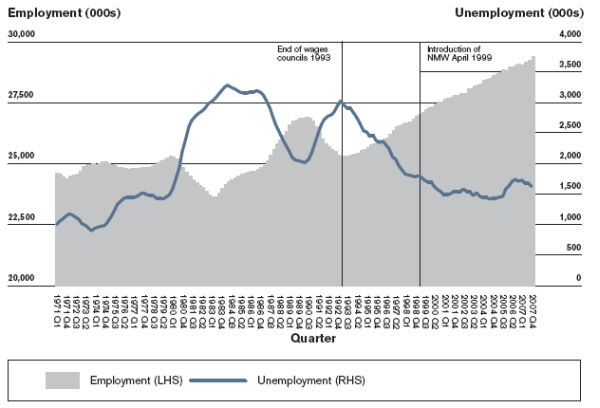

The UK Low Pay Commission (LPC) was established in 1997 and was given the task to define an effective National Minimum Wage (NMW). The following graph is taken from his Figure 1 (page 15) and is self explanatory.

Machin’s commentary is as follows:

The NMW was introduced in April 1999 at an hourly rate of £3.60 for those people over 21 years of age, with a development rate of £3.00 for those aged 18 to 21 years. The key economic question has been the impact of minimum wages on employment … Over the period 1999 to 2007, the macroeconomic picture indicates that employment continued to grow as minimum wages rose (Figure 1).

What about effects on specific age cohorts. Machin concluded that:

Across all workers, there was no evidence of an adverse effect on employment resulting from the introduction of the NMW.

What about the effects in the most disadvantaged sectors? Machin reports on research that “searched for minimum wage effects in one of the sectors most vulnerable to employment losses induced by minimum wage introduction, the labour market for care assistants”.

He concluded that:

Even in this most vulnerable sector, it was hard to find employment losses due to the introduction of the minimum wage.

Conclusion

While the $26 per week increase is welcome it is insufficient to restore the relativities at the bottom of the labour market which have been eroded over recent years.

Further, today’s decision to does not redress the significant erosion of real purchasing power that low-paid workers have suffered over the last decade. I would have used the next several minimum wage decisions to ramp up the level and restore the previous relativities with the average earner and the FMWs purchasing power.

I would also note that a sophisticated society requires a decent minimum wage that is determined on the basis of what we want the floor in living standards to be. In the absence of regulation it is almost certain that the “market” would drive the wage below that level.

In such cases, the employment is not desirable and so a Job Guarantee could set the minimum alternative employment that the private employers then have to better. They need to invest and ensure productivity can support the higher wage level. Its called a win-win.

That is enough for today!

cobbling together themes in the last 2 posts, the following link shows the disparity of earnings quite neatly (top chart)

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2010/06/the-anglosphere-and-highincome-concentration.html

Hi Bill,

Could you give us your opinion of the Resource Super Profits Tax (RSPT), please?

Regards,

Andrew

> The minimum wage is a statement of how sophisticated you consider your nation to be.

But what exactly do you mean by “sophisticated”? An online thesaurus suggested “cynical” as a synonym!

> Minimum wages define the lowest standard of wage income that you want to tolerate.

> In any country it should be the lowest wage you consider acceptable for business to operate at.

Not quite – it should be the lowest wage considered acceptable for businesses to employ people at. It may sound like splitting hairs, but I suspect many self employed people will appreciate the difference.

> Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

You’ve got that the wrong way round – the ability to use the minimum wage to meet your social objectives has to be conditioned by capacity to pay conditions.

> If small businesses or any businesses for that matter consider they do not

> have the “capacity to pay” that wage, then a sophisticated society will

> say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in their economy.

> Firms would have to restructure by investment to raise their productivity

> levels sufficient to have the capacity to pay or disappear. The outcome is

> that the economy pushes productivity growth up and increases standards of

> living.

But that’s just one possible outcome. Another is that previously viable businesses are forced to move overseas. Yet another is that they’ll shut down completely.

> No worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable

> standard of living just because low wage-low productivity operator wants

> to produce in a country.

STANDARD OF LIVING IS NOT MEASURED IN DOLLARS (or any other currency). The previous British government made that mistake, and rising wages did not translate into a higher standard of living. House prices skyrocketted so that often it didn’t even trantslate into higher disposable income.

Also, a low wage-low productivity operator could only produce in a country if they were able to find enough people willing to work for those low wages, which is only likely if the alternative is unemployment. And if the alternative is unemployment, it is difficult to justify denying people the opportunity to work for them.

“The previous British government made that mistake, and rising wages did not translate into a higher standard of living. House prices skyrocketted so that often it didn’t even trantslate into higher disposable income.”

That was because of structural issues in the housing market. Nothing to do with wages. Primarily that land is a monopoly good and there is no levy for failing to utilise it. Hence we have land banking and other nefarious monopoly practices.

“Not quite – it should be the lowest wage considered acceptable for businesses to employ people at. It may sound like splitting hairs, but I suspect many self employed people will appreciate the difference.”

The lowest acceptable capitalist wage is zero – slavery. Capitalism will enslave nations and externalise any costs it can if left unrestrained. That’s why we have laws – control rods in the capitalist nuclear reactor.

I’m self-employed and I appreciate that competing with somebody who doesn’t look after their staff as well as I do puts me at a disadvantage. I would like them taken out of the game. Yes I will adjust prices upward as much as the market will allow afterwards.

We had this argument when the minimum wage came in, and no doubt when unemployment benefit was introduced. You can view a job guarantee as ‘unemployment benefit’ where society derives value from an individual (and an individual gains value) rather than paying them to do nothing.

People don’t exist to support businesses. Businesses exist to support the people. Churchill’s words are the best: a safety net above which all may raise, but none should fall.

Neil Wilson –

Of course it was because of structural issues in the housing market. But claim that it was nothing to do with wages is completely wrong, because one of the main constraints on house prices was what people can afford. However my point was that standard of living is determined by factors other than wages. Indeed reducing the cost of living is, though more difficult, a much better strategy than just trying to force up wages. See http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/natint/stories/s1533804.htm

> The lowest acceptable capitalist wage is zero – slavery.

Most capitalists would not regard that as acceptable.

> Capitalism will enslave nations and externalise any costs it can if left unrestrained.

> That’s why we have laws – control rods in the capitalist nuclear reactor.

Strawman – nobody’s disputing that we should have laws!

> I’m self-employed and I appreciate that competing with

> somebody who doesn’t look after their staff as well as I do puts me at a

> disadvantage. I would like them taken out of the game. Yes I will adjust

> prices upward as much as the market will allow afterwards.

And so the benefits flow to the few (the employees) rather than the many (the customers).

> We had this argument when the minimum wage came in, and no doubt when

> unemployment benefit was introduced. You can view a job guarantee as

> ‘unemployment benefit’ where society derives value from an individual (and

> an individual gains value) rather than paying them to do nothing.

But we don’t have a job guarantee.

> People don’t exist to support businesses. Businesses exist to support the

> people. Churchill’s words are the best: a safety net above which all may

> raise, but none should fall.

I’m all in favour of a safety net, but I don’t believe providing it should be the role of businesses. Supporting their employees isn’t their raison d’etre, nor should it be.

Dear Bill,

Very interesting post. The capacity to pay is an important concept that firms need to deal with when they consider operations. Instead of paying the social reproduction cost of labor they want to reduce their private cost by running inflation with market power rather than paying for private investment and costs of rearranging the mode of production (adequacy) with innovation. Mantaining unemployment as a reserve privately and socially they can fight off any wage inflation that can preserve the real wage. Thus it is not surprised that during times of high unemployment real wages and wage purchasing power decline and in decreasing unemployment from investment growth and expansionary fiscal policies we see real wages and wage purchasing power face less erosion (there is an asymmetry of course!). Good old Marx here that supports your position!

The opposite occurs.

During boom times, prices rise faster than wages –> capital captures most of the surplus

During busts, prices fall faster than wages –> capital takes most of the loss

The problem is when the government prevents capital from taking the loss during the busts — for example, by preventing the bust or otherwise guaranteeing assets — but does not somehow boost wages during the boom. In that case, you have stabilized capital income but real wages are falling, and this puts downward pressure on NGDP and therefore yields. In that case, you need more and more stimulus from outside the system to keep NGDP growing (and real wages falling).

… In other words, inflation is the enemy of real wages, and the friend of capital income. Inflation *volatility* is the enemy of everyone, because it’s difficult to make investments or manage spending in that environment. So an argument that we have an unemployed buffer stock to manage inflation or suppress real wages doesn’t hold. First, the unemployed are not going to be competing with the high wage earners, whether they find work or not. It will not boost or lower the salaries of the in-demand professions.

Rather I think the buffer stock of unemployed is a symptom of our economic priorities. It does not “accomplish” anything positive for capital, and is a slight negative (due to income effects). But the private sector cannot fully employ everyone, and a society in which the power is in the hands of the wealthy has, in its interests, a desire to show that we are living in the best possible arrangement. As a result, it is the fault of the unemployed that they are not working, and it would be harmful to intervene on their behalf.

But it’s absurd to think that if the unemployed managed to find some poorly paid service work, that this would either put upward pressure on wages or inflation, or that this would take money out of capital.

“During busts, prices fall faster than wages -> capital takes most of the loss”

Lets talk about some asymmetries – unemployment is higher during busts. To say that government “prevents” capital from taking the loss during busts assumes that the state and capital have some kind of fundamental rather than formal separation of interests.

Also, I am becoming more of the persuasion that inflation is the enemy of creditors and that it is precisely during a deflationary period that real wealth is concentrated and incomes crater. There is nothing I would rather be doing than repaying banks with “debased” currency – they can have it all as long as I have continue to have access to it. That would be justice for banking’s collective crimes – actually being repaid for debts they had no intention of ever collecting in full.

Inflation expectations were serious prior to summer 2008 – shows what the public knows – didn’t think about what a mild deflation could do.

The only way to ignite inflation in the economy is through wage income increases (exception: raw material disruption) – there will be price adjustments as part of a cost push and some interest rate increases, but debt load will be reduced – it’s a form of debt restructuring that doesn’t require as severe human suffering as foreclosure and unemployment, although a many of us would bitch while we drink our $20 pints (which we could afford on our ridiculously over-priced wages).

RSJ,

I suggest you read carefully what I said about inflation and market power. Furthermore, about investment, fiscal expansion and innovation and their effects upon demand and why they are beneficial to productivity that can sustain real wage. All the rest has nothing to do with my comment regarding the capacity to pay. As about the evidence you are presenting (what about the period 1945-1965) and then explaining it with other factors is another example of spurious thinking. Why all this discussion in the rest of your comments? When did I say that before? I presented a hypothesis about the capacity to pay! Of course there could be other factors but we need to be disciplined in our analysis and not mix up relationships.

RSJ,

If you are interested to consider the role of unemployment, realize that in a situation of asymmetry ( I presented this before) the firms can offer a nominal wage that is consistent with labor aspirations and then procceed to employ subject to demand (leaving a reserve unemployment) and run inflation if they have market power to reduce the real wage. Unless investment demand and fiscal policy raises employment reducing unemployment without inflation, so the real wage is sustained (asymmetry again!). What is you do not understand? Is this model correct? It is hard to say because there are many other factors such as the financial sector via inflation beyond full empolyment, institutional factors, etc., that influence the real wage!

Dear Bill,

You are a labor economist with a lot of research in the labor markets and relations and knowledge regarding the empirical evidence in this field. Although I have read some of the theoretical literature on the subject and I have taught a course I am not as familiar as you are. Please answer the following;

1. In a previous comment I presented a hypothesis regarding your idea of the “capacity to pay”. How do you find this hypothesis?

2. What is the empirical evidence regarding the relation among growth, employment and the real wage?

Sorry this is going to be off topic. If there is a place where Bill would prefer to post off topic comments then I can do that.

anyway, I’m looking for any papers or books which deal with the justification for why the central bank and treasury can be consolidated. Frequently I am finding that people object to the realism of the consolidated government. My responses are:

1. It is consolidated from the perspective of the private sector in that it doesn’t use ‘state money’, instead transactions between the two are merely internal transactions. But this point still presupposes the consolidation.

2. Historically the central bank was created as a clearing house for banks but also as the government’s bank.

3. That all central banks are required to give their ‘profit’ to the treasury at the end of each year.

4. That the treasury and central bank are required to work together so that the central bank can maintain its target rate.

anyways, I’m sure there are more reasons why. I don’t mind if people just post other arguments but if you have a paper, book etc, (a paper by Wray and Bell comes to mind) then that would be appreciated.

Aidan:

Bill is very clear on distinguishing nominal and real wages. Increasing real wages for workers WILL increase their standard of living.

“> The lowest acceptable capitalist wage is zero – slavery.

Most capitalists would not regard that as acceptable.”

Really? Who ran the slave trade – communists? Who are the people paying third worlders less than a dollar a day to make crappy sneakers for 14 hours? Are you seriously suggesting that if a corporation could somehow get a hold of slave labour, it would be at a competitive disadvantage? Don’t tell me people would boycott them – Nike still makes a huge profit and everyone knows what they do. Your idealized view of the markets is not borne out by reality.

“And so the benefits flow to the few (the employees) rather than the many (the customers).”

When is a customer not an employee?

“I’m all in favour of a safety net, but I don’t believe providing it should be the role of businesses. Supporting their employees isn’t their raison d’etre, nor should it be.”

Providing a safety net should be the responsibility of the government – and it should do it by either setting a minimum wage or providing a job guarantee.

“> Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

You’ve got that the wrong way round – the ability to use the minimum wage to meet your social objectives has to be conditioned by capacity to pay conditions.”

No, you missed Bill’s point and have it the wrong way around. Businesses are there for people, people are not there for businesses. If a job is not profitable unless it pays a soul-crushingly low wage, then it should not exist. If it really needs to be done, then pay a decent wage. Your prioritisation of organizations over people is inhuman, and leads to the same outcomes that we saw in the Soviet Union, where the collective always came first to the detriment of the individual. All these measures have to be evaluated by how they impact on actual people, and if someone can’t make millions by paying people awful wages, then all the better!

MDM

See Randy’s description on page 7 of this paper http://k.web.umkc.edu/keltons/Papers/501/Seigniorage%20or%20Sovereignty.pdf

I agree with most of what Aidan says. Like Aidan, I’m self employed. The latter tends to force one to relate economic theory to reality in a way that is sometimes lacking in academia. Note that Warren Mosler actually runs a bank.

Grigory Graborenko says “If a job is not profitable unless it pays a soul-crushingly low wage, then it should not exist.” Wrong. If the latter sort of job is the best available for a particular person in a particular place at a particular time, then the job SHOULD exist. It will result in GDP being larger than if the job did not exist or was banned. It will or can lead to Pareto optimality.

Obviously the take home pay of the employee should not be crushingly low. In other words the state should make up the wage to the socially acceptable level. Indeed the latter principle is already in effect on a HUGE scale (at least in the UK) in that a sizeable proportion of the workforce get “in work” benefits (e.g. extra cash from government for those in low pay jobs and with several kids).

Of course the availability state support for low paid jobs leads employers to exploit the situation: creating low paid jobs with a view to getting the state to subsidise such jobs. But I can think of counter measures.

RSJ, I find your first graph very confusing and have many questions about your argument. E.g. changes in participation rate which will boost per capita GDP but there is no automatic driver of wages. Then I have doubts about your separation of production and services. Obviously GDP is much more driven by services today but your graph makes reference to production only comparing it to the whole GDP output. Next, shouldn’t you take GDP per employed capita as there might be a lot of capita drivers which are not related to GDP production per se.

Ralph & Aidan, the idea of limited resources and unlimited needs clearly defines which jobs have right to exist and which do not. A job which financially can not justify its existence means that there should be better way to use this resource rather than use the monetary power of a sovereign to prop up this particular wasteful usage. Then the task of sovereign is to use its monetary power and come up with a better, i.e. more value adding job. And the argument of Bill, if I understand it correctly, is that the government should set and move the hurdle for private sector which should drive productivity higher rather than drive resource rents higher that private sector wants to extract from _all_ resources available.

MDM,

The reason treasury and central bank accounts are not consolidated operationally is to prevent the government from using the central bank to finance the deficit. The salient feature of the unconsolidated structure is the existence of the bank deposit account that treasury keeps on the books of the central bank. That account must be kept at a positive balance, and therefore requires debt financed inflows before corresponding deficit expenditure. The account would disappear with operational consolidation, allowing free form deficit spending. The whole point of the deconsolidated structure is that it imposes the financing constraint that MMT wishes to see eliminated.

Arguing the merits of the financing constraint is a separate topic. But that’s why the system is not consolidated operationally.

Bill has not responded to my questions and I would like to elaborate further on his concept of “capacity to pay’ and the hypothesis I assume it is behind it. Today I have more time and my comments yesterday were short.

First, let us present the asymmetry ASSUMPTION of imperfection. Firms have an information advantage regarding their products over consumers. On the other hand, workers have an information advantage regarding their skills prior to their employment. Thus asymmetry assumption implies that firms set the price of their products, not neccessarily equal to the notional value expected by the buyer and the quantity is set by the buyer, also not neccessarily equal to the notional level required by the firm. Similarly, workers set their aspiration nominal wage, not neccessarily equal to the notional value for the firm and the level of employment is set by the firm given the level of demand for its products, also not neccessarily equal to the notional level required by the worker (ONE source of involuntary unemployment). If we can agree on these behavioral relationships we can procceed further.

Firms have a mode of production based on their technology and any market power in their product and resource markets. This mode reflects a fixed productive capacity with a fixed level of indirect labor (Minsky) while output changes with a variable direct labor employment. (Notice that I have presented a simple model of AS and price level functions reflecting this mode of production concept in a comment May 18, at 2:00). The technology/product market power mix (business leverage) allows for price rises at lower output levels and these reduce real wages, one source for the capacity to pay wages by firms.

Similarly, any labor market power of firms allows, in the presence of higher nominal wages aspired by workers, the employment of less direct labor, given the fixed indirect employment capacity (employment leverage). This implies a proportional employment gap which is equal to the reserve unemployment (Marx) that can be reduced when there are increases in product demand. The reserve level of unemployment helps the firm capacity to pay by controling nominal wage aspirations by workers. Notice that productivity rises when by innovation the firms reduce the indirect to total employment level so that real wages can be sustained or even rise.

During times of rising product demand that can be induced by fiscal expansion, investment growth, exports, etc., firms increase direct employment, raise their productive capacity with embedded technology and lower the indirect to total empoyment ratio via innovation and these factors as a whole raise productivity. Thus the firm capacity to pay higher nominal wages or sustain existing ones increases and prices do not have to rise. Real wages in this scenario can be sustained or raised as long as labor is unemployed. At full employment firms raise their prices in excess of nominal wages if they have market power so real wages decline assuming there is financial accomodation of price increases. However, there are forces that can affect this scenario such as monetary policy, debt growth, interest payments and institutional factors that can alter price and wage inflation.

Scott,

Thank you for the article. Wray makes a similar argument in a paper with Bell.

Anon,

I haven’t had a chance to catch up on the discussions you have had here or on Mosler’s site. so you may have already been arguing against this point.

I was looking for justifications for the ‘consolidated government assumption’.

For those interested this is what Wray says (Note I haven’t read the paper in any great detail yet):

“Obviously the take home pay of the employee should not be crushingly low. In other words the state should make up the wage to the socially acceptable level.”

No. That is subsidising the crushingly low wage, allowing that company to exist in a market when it shouldn’t. Why should businesses that pay a living wage subsidise those that don’t? That’s the fundamental problem with tax credits, housing benefit, unemployment and the rest. They are ultimately subsidising exploitation of the work force.

Much better that the public sector sets the minimum wage, and provides jobs at it (in place of all the other benefits). The public sector then gets the value of the individual rather than the private sector. The private sector then has a choice – allow the public sector to grow absorbing people (which ultimately the exchange rate movements would ‘fund’), or come up with ways of employing people at higher rates of pay (ie work on productivity improvements to make people worth more).

MDM,

Yes that was a long discussion! To help you appreciate your reading, here’s something from me.

This is what neoclassicals think:

Some of them do know the operations between the central bank and the government but fail to see its implications and questions such as “what is money?”. The amount of money M (some monetary aggregate such as M1, M2 etc.) is fixed by the central bank. Borrowing reduces M and since this leads to a scarcity, interest rates go up which prevents the government from spending more and simultaneously leads to increased borrowing costs for the private sector (the “crowding out”). They fail to see that firstly, the central bank does not and cannot control the money supply (any such target will be harmful for the economy) and secondly, that the government borrowing replenishes the system by government spending. Non-observance of crowding out is “explained away” saying that the central bank monetized the debt – i.e., that the central bank purchased government debt.

And how does inflation happen according to neoclassicals/monetarists ? They will claim that the central bank purchased government debt and since this creates reserves, banks will “lend out those reserves” (as if, if the reserves increase by $10b, the banks will lend out $100b assuming a reserve requirement of 10%). Some neoclassicals will know that banks can’t lend those reserves out, but think that it will give them more capacity to lend etc. So according to this theory, debt monetization leads to price rise.

But how does budget deficit lead to price rise in this silly neoclassical theory ? Their story is that since deficits lead to crowding out, possible government default etc, the “non-independent” central bank monetizes part of the deficit and then on top of that the story of banks lending those reserves out. So that is why you see so much “independence” of CBs written all over the media and neoclassical economists’ papers.

That in brief is the neoclassical theory of central banks and governments.

MDM,

Not arguing one way or another, and haven’t done so – just pointing out some facts.

Wray doesn’t really make an argument for consolidation. What he says is that consolidation is operationally feasible, and de-consolidation is a nuisance – because non-MMT economists aren’t smart enough to understand it.

Neither of those things are effective arguments for consolidation. They are advantages in implementing consolidation, but not reasons for it.

Moreover, he says:

“Procedures that they have imposed on themselves and which are not dictated by logical necessity”

The fact is they are logically necessary – if you want to prevent the government from deficit spending via net money creation.

Again, the debate should be focused on that last point, rather than the elegance of operational consolidation as a purported rationale on its own.

Wray says:

“As we have seen, a nation that operates with a fiat money on a floating exchange rate, treasury debt is really nothing more than reserves that pay interest, and the purpose of sovereign debt issue is to drain excess reserves to allow the central bank to hit its overnight interest rate target. This really cannot be called a borrowing operation… it makes no sense to argue that a government operating in such a system needs to borrow its own liabilities in order to deficit spend.”

This is factual/counterfactual conflation.

The fact is that in the present deconsolidated system the treasury does borrow, but it does not borrow its own liabilities. Wray himself admits that most taxes (and therefore bond settlements) are paid in “bank money” rather than fiat money. That is mostly what the treasury is borrowing in the deconsolidated system.

The description “is really nothing more” refers to the consolidated counterfactual system. It is an implicit structural conversion that MMT should make more explicit more often.

Bill, although I agree completely with your analysis, and the direction you took in this post, it omits a key factor.

In our shrinking, globalised world, production will naturally gravitate to the country with the lowest production costs. Your statement “No worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable standard of living just because low wage-low productivity operator wants to produce in a country.” ignores the point that there are huge differences between countries as to the “lowest tolerable standard”.

By ignoring this, we finish up with huge trade imbalances, and an unsustainable global economy.

I’d be delighted if all countries in the world shared our standard of living. But it appears that that is just not sustainable. So, where do we go from here? Protectionism? Capital controls?

Ramanan,

Thank you for that. To be honest, I’m not sure what the mainstream position is. When I ask my lecturers and professors whether the money supply is endogenous they have all said “yes, it is”, some have even added that it has a horizontal supply schedule and that there Post Keynesians are going on about nothing, as the mainstream accept that the money is endogenous. There is always the possibility that the two schools mean something different when they say endogenous money, but I am unsure.

Anon,

I didn’t mean the ‘consolidated government assumption’ as a policy prescription, rather I was asking for the justification for why that assumption is used in MMT models. The quote by Wray is NOT a policy prescription rather it is a justification for the assumption that the government can be treated as consolidated (for operational purposes) with no significant consequences or limitations arising from this. In order words it is an assumption to simplify the theory/model.

When Wray states that taxes are paid in bank money he is talking about it from the perspective of the non-bank private sector. So for anyone who has a deposit account, they can use this to pay taxes BUT behind the scenes, that banks reserve account is being debited down by the equivalent amount. So yes bank money from the perspective of the non-bank private sector is used to pay taxes but in actuality it is governments liabilities (reserves) which are extinguishing the liability.

When the government debits tax and loan accounts (borrows in your words) it isn’t doing this in order to spend. Rather it is doing this to minimise its ‘reserve effect’ – which makes the central banks policy of maintain its target rate more difficult and volatile. Furthermore it isn’t borrowing bank money. Tax and Loan accounts are the temporary ‘storage devices’ used to minimise the reserve effect arising from taxation. They exist as deposits which have a corresponding reserve but that cannot be used for any other purpose (though in certain circumstances bonds may be purchased with them). So the treasury isn’t borrowing bank money (bank credit) it is debiting the tax and loan account and therefore drawing down the bank’s reserve account.

Anyway I am trying to write a political economy essay on the atomistic and organic theories of the state so I may not be able to respond for a while.

If I have made any mistakes please point them out.

MDM,

Probably the lecturers have picked up “endogenous money” but I am sure that they live in the same old paradigm. For example, if you read Nouriel Roubini, you can see that he is always arguing about the dangers of debt monetization and inflation. So what I outlined is essentially the mainstream position. On the other hand, its funny – since the mainstream theory is so self-inconsistent, there is room for including endogenous money and remaining inconsistent. For example in one of John Taylor’s texts, he seems to adopt the view that money is endogenous and then later goes on to the same old multiplier story. I am not even sure if they understand the horizontal supply schedule. They may mention it in one chapter and then use Stiglitz’s theory of credit rationing where the supply is not horizontal. The horizontal supply schedule is not so obvious. The detailed mechanism on how interbank markets make it so is not written elsewhere than in Post Keynesian literature. There are more detailed dynamic mechanisms at work to make it so too.

One way or the other, neoclassicals are “Verticalists” in the sense used by Basil Moore – with the exception of Michael Woodford.

“The quote by Wray is NOT a policy prescription rather it is a justification for the assumption that the government can be treated as consolidated (for operational purposes) with no significant consequences or limitations arising from this.”

You’re right. It’s not a policy prescription. And that’s exactly my point all the way through. The fact is that there IS a significant consequence arising from operational consolidation, as I described. So its not an adequate justification.

The consequence is that operational consolidation means that the government treasury integrates the central bank into its own operations. That’s what allows it not to issue bonds. It uses the central bank like an unlimited credit card, where it simply spends and creates bank deposits and bank reserves. Nothing operationally constrains it from doing that. That’s the structural foundation for the MMT “theory”. But it’s a counterfactual monetary system structure.

The point is that this requires a change from the existing operational configuration, which is overdraft constrained and bond constrained.

MMT “theory” about how the system works is based on its own counterfactual, not the factual.

So it is inconsistent “not to prescribe policy” when at the same time describing the operation of a counterfactual system that requires a structural change from the factual system.

Working in reverse, again, the reason for the unconsolidated operational structure now is to prevent the operation of the system according to the way MMT defines as “intrinsic”.

The idea that reserve transactions replicate “clearinghouse” transactions is factual but not very relevant here. There are no net reserves in a zero reserve system like Canada’s. Reserves are a clearing and settlement device. That they are used directly in settling up with the government’s central bank is of no particular significance other than the central bank must take this into account in setting system reserve levels after ALL system transactions are taken into account.

And Wray himself says in the article that most taxes are paid with bank money, not fiat money. The same holds for bond settlements. Those aren’t my words. They’re his.

Anon, completely agree on this.

anon:

From Wray: “First, most payments in modern economies do not involve use of a fiat money; indeed, even taxes are almost exclusively paid using bank money.”

I think that Wray is including central bank liabilities (Federal Reserve Notes) in this sentence, in which case I don’t see the relevance. Also, I don’t understand how one can differentiate from “bank” money and “fiat” money in circulation – of course treasury debt is transformed into bank money via Fed Reserve – but are you saying that only money with corresponding private liabilities are what is “borrowed” by the Treasury? If that is really what is operationally happening, how do net financial assets increase as the economy grows? It would seem that net financial assets are then contingent on private bank behavior – which I can understand as a goal that private interest would want to accomplish.

pebird,

Wray includes reserves and currency in his definition of fiat money – i.e. liabilities of the central bank.

(He “extends” this definition loosely to government bonds, when he wants to use it in a broader context, since bonds are another form of government liability.)

The key is that his definition requires that fiat be a state liability.

Commercial bank deposit liabilities are not fiat.

So the government is borrowing non-fiat money, operationally, in the case of non-bank bond buyers (i.e. the bulk of bond buyers).

The government spends from its central bank account, as described earlier.

When payees of government expenditures are non-banks, they are credited with commercial bank deposits. This again is non-fiat money.

The central bank controls the final level of reserves quite independently, taking into account the net effect of this spending and borrowing and tax activity.

Net financial assets are created when the total of new reserves, currency, and bonds created in a given period is balanced out against the total of government spending net of taxes for that period. The fact that bonds are purchased mostly with non-fiat money (the same as Wray says for taxes) is not necessarily inconsistent with the fact that bonds end up being net financial assets for non government.

More generally, non-fiat money can be exchanged routinely for fiat money – bank deposits for currency, and bank deposits for bonds (if you want to extend your definition of fiat to bonds).

Septimus here’s my attempt at an answer from an Australian perspective (easily translated to any advanced post industrial economy). Australia is a service economy, its not like we are competing with china in a global market for widgets. Therefore all the state needs to do is set the wage level and this becomes the cost of doing business, like any input (Export exposed industries could apply for a tax credit or the like). The state can maintain aggregate demand at this level through any one of the methods previously proposed, the most effective being a job guarantee.

I feel sorry for the person who has to make my I-pod for 300 $US a month, but how does that impact on Australia, the US or any rich sovereign currency nation? We don’t need those jobs, we can buy that stuff and swap it for bits of paper and promises in the form of government bonds. The role of the state should be to ensure everybody is gainfully employed, housed and cared for inside its own borders. That is the limit of its fiscal capacity. This it can sustain as long as there are people to work, resources to exploit and life to be lived. 🙂

Professor Mitchell, thanks for the blog. Like lots of people out there its become a daily staple.

Grigory Graborenko –

> Bill is very clear on distinguishing nominal and real wages. Increasing real wages for workers WILL increase their standard of living.

If he’s so clear on it, why does he advocate increasing the nominal minimum wage rather than exploring other ways to increase real wages?

> > > The lowest acceptable capitalist wage is zero – slavery.

>

> > Most capitalists would not regard that as acceptable.

>

> Really?

Yes. Opposition to slavery today is overwhelming.

> Who ran the slave trade – communists?

Another strawman. Capitalists ran it, and capitalists abolished it. And in the American civil war, the North were just as capitalistic as the South.

> Who are the people paying third worlders less than a dollar a day to make crappy sneakers for 14 hours?

I don’t know? Are you sure they exist? The wages in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam are very low, but not THAT low!

> Are you seriously suggesting that if a corporation could somehow get a

> hold of slave labour, it would be at a competitive disadvantage? Don’t

> tell me people would boycott them – Nike still makes a huge profit and

> everyone knows what they do.

Yes – everyone knows that, despite the low wages of its workers, they DON’T use slave labour. And if they did, not only would people boycott them, but the directors may face criminal charges.

> Your idealized view of the markets is not borne out by reality.

It’s closer to reality than your cynical view of the markets.

> > And so the benefits flow to the few (the employees) rather than the many (the customers).

>

> When is a customer not an employee?

A great deal of the time.

> Providing a safety net should be the responsibility of the government

I’m glad you finally agree!

> – and it should do it by either setting a minimum wage or providing a job guarantee.

Preferably both! Indeed in the absence of a job guarantee, a minimum wage risks being counterproductive, particularly when it’s set too high.

>

> > > Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

> >

> > You’ve got that the wrong way round – the ability to use the minimum wage to

> > meet your social objectives has to be conditioned by capacity to pay conditions.

>

> No, you missed Bill’s point and have it the wrong way around.

No, I’ve REJECTED Bill’s point because I think Bill has it the wrong way around.

> Businesses are there for people, people are not there for businesses.

But the people who the business is there for are not primarily the ones who work for the business.

> If a job is not profitable unless it pays a soul-crushingly low wage, then it should not exist.

But who’s to say what “soul crushingly low” means? I was under the impression that it’s the type of work that people regard as soul crushing, not what it pays. Although better pay can compensate for this; you may have heard about Henry Ford paying his production line workers more – ostensibly so they could afford to buy the products they were making, but actually to stop them quitting in favour of less boring jobs.

> If it really needs to be done, then pay a decent wage. Your prioritisation of

> organizations over people is inhuman, and leads to the same outcomes that we saw

> in the Soviet Union, where the collective always came first to the detriment of the individual.

Individual rights are very important, and I’m not suggesting they be ignored. But denying people the right to work for a low wage doesn’t automatically give them the right to work for a high wage.

> All these measures have to be evaluated by how they impact on actual people, and if someone

> can’t make millions by paying people awful wages, then all the better!

It’s only better if the people currently on “awful wages” don’t end up eve worse off.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/jun/04/european-debt-crisis-eurobond-plan. This is besides the point. Is this the first step for the EZ to consolidate the fiscal authority and turn into a true federation?

More empirical evidence. “Country level data suggest that the largest wage increases over the last decade are generally associated with the strongest growth in domestic demand” and also higher real wages and employment growth! See http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/gros9/english. Apart from that the article has other points of analysis that I question!

Aidan:

“Capitalists ran it, and capitalists abolished it”

They didn’t abolish it because it was cheaper to, or the markets demanded it. There was something above and beyond. Basic human justice told us ‘screw the economic consequences, this is wrong!’.

“I don’t know? Are you sure they exist? The wages in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam are very low, but not THAT low!”

http://web.mit.edu/ipc/publications/pdf/02-007.pdf

Child labour, wages below minimum wage of those countries(!), and awful working conditions. This is what capitalism sinks to when no one’s looking.

“> When is a customer not an employee? A great deal of the time.”

Not really. You are making the classical mistake of seeing supply and demand as independent. Customers get the vast majority of their money from their employment.

“If he’s so clear on it, why does he advocate increasing the nominal minimum wage rather than exploring other ways to increase real wages?”

He does. Often he talks about wage share and profit share, and how the large pool of unemployed give governments and businesses excuses to deregulate labour markets. MMT has many facets, but it the end it’s just a description of how things are – not a policy prescription. Bill’s personal policy views are to improve long-term living standards for everyone by any means necessary, be it minimum wage, JG or whatever.

“But the people who the business is there for are not primarily the ones who work for the business.”

Stop thinking about what’s good for the market for a moment, and reflect upon why the market is there at all. Why do we even have businesses at all? Why is competition worthwhile? There was a time in human history when there was no market, and we lived in a nomadic/subsistence fashion, and we could return to that if we wanted to. Why don’t we? Because in the end, the market, and capitalism in general, mean we can live better lives. Thats the real bottom line. So this deference to business, an abstract organization, at the expense of actual human beings, really puzzles me. Business is there for everyone, including the employees. In some ways, especially for the employees.

“Although better pay can compensate for this”

Exactly!

“It’s only better if the people currently on “awful wages” don’t end up eve worse off.”

Relax, they won’t. As Bill and others have stated, research shows employment growing when minimum wages go up. Everyone wins, except the shareholders that profit off the backs of underpaid labour. So you’ll be OK unless you own a McDonald’s franchise (which seems likely for some reason).

“As Bill and others have stated, research shows employment growing when minimum wages go up. ”

They may have stated it, but is it confirmed? One of the problems with economic research is that it is almost always non-conclusive and arguable.

I have a feeling this argument has to be put forward in the same way as health care, education and personal liberty. Removing capital’s ability to profit from temporary casual minimum wage labour is the right thing to do, much as universal health care and public education are the right things to do.

Business and the market can then adapt to cope with those minimum standards or perish.