This is a second part of an as yet unknown total, where I investigate possible…

Bank of Japan’s ETF sell-off is a sideshow

On September 19, 2025, the Bank of Japan issued its latest – Statement on Monetary Policy – where they announced that there would be no change in the overnight call rate (the policy rate). However, they also announced that they would begin selling off their holdings of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and Japan real estate investment trusts (J-REITs). Many people are unaware of what these assets are and why the Bank of Japan would be holding them. Further, the media went wild and the Japanese share market gyrated (down) upon the news, suggesting that there was something significant going on or that the ‘markets’ are just dumb. It was the latter by the way. However, this has become an issue in Japan and this blog post is about sorting through the nonsense.

The September 19, 2025 announcement said:

… the Bank decided, by a unanimous vote, to sell these assets to the market in accordance with the fundamental principles for their disposal, which include the principle to avoid inducing destabilizing effects on the financial markets. The scale of the sales will generally be equivalent to that for the “stocks purchased from financial institutions”

The Bank stopped buying these assets in March 2024 as it concluded that “the price stability target of 2 percent would be achieved in a sustainable and stable manner.”

So now, more than a year later, the Bank announced it would start selling these assets off using the following guidelines:

(1) dispose these assets for adequate prices, taking into account the situation such as the condition of the ETF or J-REIT market, (2) avoid incurring losses as much as possible, and (3) avoid inducing destabilizing effects on the financial markets as much as possible.

The latest – Bank of Japan accounts (issued on September 24, 2025) – show that:

1. Total assets – 710,701,760,867 thousand yen.

2. Japanese government bonds – 572,147,949,539 thousand yen or 80.5 per cent of total assets.

3. Pecuniary trusts (index-linked exchange-traded funds held as trust property) 37,186,178,276 thousand yen or 5.2 per cent of total assets.

4. Pecuniary trusts (Japan real estate investment trusts held as trust property) 655,021,089 thousand yen or 0.09 per cent of total assets.

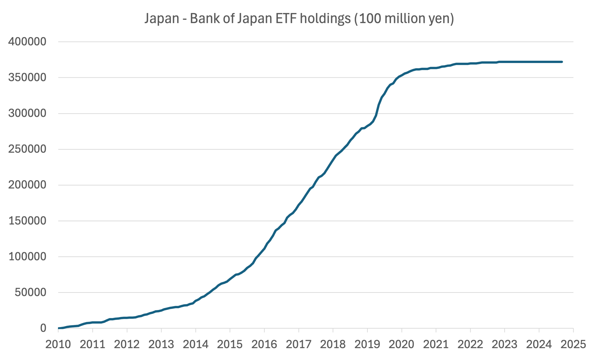

This graph charts the Bank’s ETF holdings since December 2010 up until August 2025 (latest time series data).

The REITs graph (not shown here) follows a similar trajectory albeit at a much lower scale).

So there was a continuous process of acquisition

Th Bank will start selling its stock back into the market at 330 billion yen a year for ETFs and 5 billion yen per year for J-REITs will constitute “about 0.05 percent of the trading values in the markets”.

So very small impact.

So what is going on?

Is this problematic?

This saga all began in October 2010, at the height of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when the Bank of Japan decided to start speculating in the Japanese share market.

The speculation was seen as an essential part of its Large-Scale Asset Purchasing (LSAP) program, which had been focusing on the purchase of Japanese government bonds since 2001 and its zero interest rate policy that began in 1999.

The new purchase plan was absorbed into its – Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) which they announced on April 2013.

The decision by the Bank of Japan to start buying products linked to the share market was quite a deviation from normal central bank practice – rarely do central banks buy shares.

It had bought shares of some individual banks between November 2002 and September 2004 as part of a plan to underwrite their viability.

These purchases were designed to ease the non-performing loan problems that were an overhang from the asset bubble collapse in the early 1990s.

In other words, the Bank of Japan feared there would be a collapse of some leading banks and as a stability policy they bailed them out.

This was not motivated as a monetary easing policy,

So the Bank of Japan moved in and bought up shares held by the commercial banks that were rated at BBB- and above.

By September 2004, when the program was discontinued, the Bank of Japan held 2,018 billion yen of such shares and they started selling them again in October 2007 but then ended the sales as financial markets deteriorated in the lead up to the GFC.

The purchases resumed in February 2009 because the Bank of Japan assessed that the commercial banks were recording massive losses from non-performing loans which threatened their solvency.

They ended this phase in April 2010 adding a further 388 billion yen to its holdings.

The essential point is that these purchases were not about monetary easing.

But the ETF purchases was another matter altogether.

On October 2010, the Bank of Japan announced its – Comprehensive Monetary Easing (CME) – policy, which was explicitly designed as a monetary easing approach.

It was considered to be highly unconventional, although that is a Western loaded term.

The asset purchase program was one part of CME, which was dominated by the purchase of JGBs.

The Bank had already been purchasing risky (non-government) assets as noted above.

But it extended that approach – in a very unconventional manner – by buying up ETFs and J-REITs directly in the share market.

The motivation was to break into the cycle of pessimism that the Bank believed had created a ‘coordination failure’ in the financial system.

This failure was evidenced by stagnant bank lending which arose because the banks were unable to assess the risk associated with new areas of investment opportunity.

This was a hang over from the bubble collapse.

The banks were still drowning in their non-performing loans and cutting and the Bank of Japan embarked on its CME program to help reduce the extreme pessimism (risk aversion) that had set in among investors.

The investment community basically stopped investing in what were considered to be riskier assets and this become a self-fulfilling cycle of pessimism and dysfunction.

And so the Bank of Japan started buying up these riskier assets to prop up demand and take those at most risk of collapse out of the market.

The aim was to break the risk aversion and provide a spark to struggling enterprises that were unable to attract capital.

The Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) purchases are not direct share purchases from corporations.

Rather they are considered to be indirect share purchases given these funds track the – Nikkei 225 – and the – TOPIX (Tokyo Stock Price Index).

These indexes are combinations of individual company shares traded on the share market and they created their composite using different weighting methods (Nikkei 225 uses prices, TOPIX market capitalisation).

ETFs are assets that are effectively combinations of many assets in the share market – a sort of composite index, and has the advantage that if one part of the index (a specific share) falls in value it can be offset by another share that is part of the index rising in value – so they diversify risk to some extent.

But for all intents and purposes you can think of them as shares.

The BoJ bought a massive quantity of these assets during the period beginning with the GFC as the graph above shows.

It also varied the emphasis of the program over time.

For example, in December 2015, the Bank of Japan shifted focus of their EFT purchases towards corporation that were seen to be leading investment in physical infrastructure and human capital development.

As time passed, the rate of EFT acquisition increased and I won’t take you through all the announcements that were made as to the new increments.

There was a lot of angst around 2015 and 2016, that the Bank was biasing its purchases towards shares that were included in the Nikkei 225.

In some cases, the Bank of Japan acquired more than half of the shares in some specific corporations (for example, Fast Retailing Co).

The Bank responded to these concerns by shifting its purchases more to shares traded on the TOPIX.

After some years of large-scale purchases, the Bank of Japan now owns (indirectly) about 7 per cent of the Japanese share market, which is massive.

What was the impact of doing this?

The Bank of Japan effectively became a financial market speculator and pushed the share prices up on the Nikkei 225 and the TOPIX, providing wealth gains to the already wealthy.

Foreign investors also did very well.

To some extent the different elements of the CME worked against each other in relation to share prices.

The negative interest rate policy pushed the yen up and share prices down while the EFT purchases pushed share prices up.

The starkest aspect of this exercise is that while it was a totally unnecessary operation, it has made the Bank of Japan one of the top investors in the Japanese share market.

This is an odd status to have for a central bank, particularly as the Bank does not have voting rights in the corporations it has large shareholdings in.

Many called the Bank a ‘silent’ investor.

The purchases also probably created situations where the share prices in small firms became overvalued, which distorts investment calculus.

While, the purchase of JGBs was justified because it kept the ‘borrowing’ yields down for government, given its obsession with issuing debt (another totally unnecessary operation), the ETF purchases (and REIT purchases) just provided support for the already wealthy.

It was corporate welfare writ large.

Now the Bank of Japan has a problem. It is a large shareholder in the Japanese market.

It knows that if it sells those ETFs and REITs back to the market at market prices, the increase in supply will drive the price down and private shareholders will make losses.

This is the reverse impact of the initial purchases which provided private shareholders with massive profits.

So it has to sell their ETF holdings slowly (and the governor told the media that it would take 100 years to relinquish their total holdings).

Even then it will act as a dampener on the share market, which is why there was widespread selling among shareholders immediately after the Bank of Japan announcement last week.

Conclusion

I think the Bank of Japan is smart enough though not to destabilise the share market and will tailor their sales volumes to achieve that purpose.

The point though is that the original purposes represented corporate welfare – totally unnecessary and a boon to the already wealthy in Japan.

It is another demonstration of how capitalism depends on the state for its survival.

It is likely that many more banks and corporations would have become insolvent during the GFC and its aftermath had not the Bank of Japan bailed them out with EFT and J-REIT purchases.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“It is another demonstration of how capitalism depends on the state for its survival.”

Thanks for another important post, Bill. I was just commenting on FB on a podcast by new Green Party leader Zack Polanski interviewing a young economist who introduces herself as a Marxist. By rejecting MMT she, like the rest, doesn’t understand how capitalism works.

Hi Bill, thanks for the explanation. I’m one of the many people that don’t know what these are or why the Bank of Japan would be holding them. I was just wondering if the BOJ receives dividends on these holdings and, if it did, would MMT consider dividend payments to the Central Bank as functionally equivalent to a tax?

Dear Jerry Brown (at 2025/09/26 at 12:23 am)

Thanks for the question, which opens a Pandora’s box.

Yes, the Bank of Japan earns dividends on the EFT holdings and also profit or loss on their sale. It pays profits it earns, including from the ETF dividends, to the Ministry of Finance.

In other words, the government (Bank) speculated in the financial markets by purchasing financial assets and delivered massive profits to the private sector.

It then sends the profits etc on holding and trading these assets back to itself (Ministry of Finance) and everybody thinks this is fine.

Further, there is a growing chorus here in Japan among economists, who are claiming this is a way to ‘shore up the fiscal deficit’. My god!

best wishes

bill

BoJ uses exchange-traded funds (ETF’s) because its goal is to provide financing, not to “own the means of production.”

Share ownership is company ownership, even when only a fraction of the available shares are owned. Direct share ownership entails responsibilities, such as choosing among competing slates for boards of directors and voting on significant corporate actions. The BoJ wishes to avoid having to make potentially controversial choices like these. ETF managers step in to relieve the BoJ of the responsibility to vote its shares.

Higher stock prices make increased capital investment more appealing to stockholders who, in turn, press management to expand capital expenditures. Higher stock values also relieve debt pressure on firms by allowing them to undertake actions to substitute equity for debt.

The increased capital investment and reduced debt pressure on firms are what the BoJ seeks through ETF purchases.

The BoJ wants to provide financing without taking ownership.

Thanks. I am just trying to figure out what possible redeeming qualities this policy might have had. Or whether it falls into the usual ‘socialize the losses, privatize the profits’ game that is generally played.

Another indication governments should not be selling (or buying) bonds – or ETFs for that matter.

Government *debt monetization* is rejected because of the risk of inflation, but there are alternative methods to control inflation other than via “central bank independence” manipulating interest rates.

But I wouldn’t expect people who think “opportunity costs” are more important than ensuring everyone is decently housed would be interested in examining said alternative methods of inflation control….

Neil Halliday: You keep revealing your lack of understanding of the opportunity cost (OC) concept and the fact that OCs don’t disappear if you ignore them. They accompany every benefit, and they matter! Many OCs have been, and continue to be, ignored to the detriment of us all.

You also need to carefully read what I write. With a grounding in Ecological Economics, I place ecological sustainability first (nothing matters if it isn’t sustainable), distributional equity second (full employment and decent housing for all for starters), and allocative efficiency (where considerations of OC matter) third.

Philip,

I regard the concept of ” opportunity cost” (OC) itself as flawed, being based on *free market* ideology.

eg, when I suggested to a well known mainstream economist the BIS should purchase the entire global fossil industry with money created ex nihilo, in order for the globe to speed up transition to a green economy, he pointed to OC as the barrier.

In fact *choice* – not “opportunity” – is the important consideration.

We need to *choose* to utilize resources to implement a sustainable economy, not be diverted by the free-market-based concept of “OC”.

How can humanity transition to a sustainable economy without *central planning* in the macro-economy (as opposed to “OCs” in the micro – market – economy)?

Hence housing everyone (in a sustainable economy) is a necessity; “OC” is relevant only for *resource allocation* in profit-driven private-sector markets.

Neil Halliday: There is no point in me trying to convince you of the importance of opportunity cost (OC). You simply don’t ‘get it’. OC is as real as the Earth rotates around the sun. There is no ‘choice’ in the matter in the sense that when a real resource is used for a particular purpose, it can’t be used for another purpose. If you don’t believe that, don’t argue with me. Go and argue your contrary view with a physicist.

In a nutshell, when a resource is used for a particular purpose, you/we forego its use for another purpose. Surely you can understand that. If you can, then you are part of the way towards understanding the OC principle, since OC is the next best alternative use of a resource that is foregone – the cost – from having used the resource for a particular purpose. We can debate what is the best use of a resource, and therefore what the actual OC of using a resource is. We will all differ in our opinions here. But you can’t deny that there is an OC associated with the use of any resource. Indeed, it is the only ‘real’ cost and the only real reason why Economics exists as a sub-discipline. If we lived in the Garden of Eden, there would be zero resource scarcity, zero OC, and we could use real resources as profligately as we liked knowing there would always be a replacement resource to use for another purpose. Unfortunately, we don’t live in that world, and so we are stuck with OCs and the need to make choices – that is, how much low-entropy matter-energy (natural resources) we extract from the ecosphere and what we do with the real resources once they have been extracted. Humankind virtually ignores the first required choice (or chooses to extract real resource beyond the Earth’s carry capacity, as we are now doing to the extent of an excessive 80% of the Earth’s Biocapacity), and does a woeful job at the second, in large part because the full OC of resource use is not adequately reflected in market prices and because many resource allocation decisions are made by powerful individuals with no concern for society’s best interests.

Phil writes:

“OC is as real as the Earth rotates around the sun”.

Obviously we are defining OC differently.

I explained why I reject Danny Price’s assertion the BIS shouldn’t buy the global fossil industry because of OC (in his opinion).

How would you transition the globe to a green economy ASAP?

The private sector won’t do it without a carbon tax which will push energy prices through the roof.

“when a resource is used for a particular purpose, you/we forego its use for another purpose”

Got it – you, Danny and I all agree on that point.

Neil Halliday: Glad to see you get the point about foregoing something when a resource is used to provide something else. Now, what would you call something foregone? A benefit or a cost? It’s clearly a cost. It is all very simple. An inability to comprehend something foregone as a cost is also the reason why some people have trouble comprehending an export as a cost to a nation (and an import as a benefit). Again, very simple.

Phil:

The Oz treasury would undoubtedly say the export of WA’s iron ore is a benefit for Oz, earning foreign exchange and enabling Oz to import stuff we need but don’t have or make ourselves.

Admittedly, in a century’s time Oz might wish it had access to the (by then) depleted ore, so….should we become self-sufficient ASAP and ween ourselves off imports?

Of course the Oz treasury can create Oz dollars out of thin air, but Oz dollars can’t pay for imports.

And how would a nation like Japan, with *limted natural resources*, develop its economy without exporting manufactured goods? (Trump of course is frothing about the success of (eg) Toyota in world markets, because those exports pauperized Detroit whose own products could no longer compete in world markets).

Dear Neil Halliday (at 2025/10/08 at 12:21)

Thanks for your continued commentary and input.

But on this topic you are conflating the components of the transaction, which is common and is the reason people cannot get the MMT external sector analysis easily.

There are two components:

1. The iron ore, which is shipped abroad and as a result cannot be used by the domestic economy.

2. The imported goods and/or services which are made possible because the exports have earned foreign currency.

The imports are the benefit.

The exports are the cost that is incurred (investment if you like) to get that benefit.

The Treasury would agree with me.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill.

So nations must incur the the costs of exports, to earn the benefits of imports.

Got it.

There remains the issue of dealing with the outcome of *trade competition* in global markets, which surely requires a *global trade oversight mechanism* to ensure a positive outcome for all nations.

Obviously the current IMF/WTO methodologies fail to achieve that desirable outcome.

And then there’s the issue of AGW/CO2 emissions; Frontier Economics’ CEO insists OC is a reason to reject BIS/IMF management of the *global resource mobilization/allocation* required to achieve net zero ASAP.

He is ignoring the different resource endowments and capabilities of nations.