I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Progressive movements bound to stall

I was going to write about manufacturing today in the light the Campaign for America’s Future staging of Building the New Economy conference in Washington DC today. I started investigating what it was about. It raises a lot of issues what a progressive position should constitute. However, I got way laid by other things which were also interesting and will leave my blog about the demise of manufacturing for another day. But what this conference demonstrates to me is that we have a long way to go before we get a united progressive understanding of the way the modern monetary system works. And until we have that understanding, no real progress will be made reforming the economy. We will always be trading off tax cuts for spending increases and all that sort of mainstream mumbleconomics and feeling defensive any time a deficit arises. And then today, I started reading the latest report from the IMF …

In terms of the Washington conference, slogans such as “Building the New Economy” sound good and some of the speakers though not known for their understanding of the way the monetary system works have written good research papers in the past. So it was worth reading a bit to see what was going on.

The Conference also released a background Research Report, which outlines the manifesto that the organisation (mostly driven by the AFL-CIO as far as I can tell) wishes to pursue.

The opening paragraph offers hope:

We can’t go back. We can’t pull out of the present downturn and return to the economy of the past – a high-consumption, low-wage economy based on asset bubbles and foreign borrowing. We need to look ahead. Our response to the current crisis must plant the seeds for the economy of the future.

I agree 100 per cent with that except I am always worried when the spectre of “foreign borrowing” is raised. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with foreign borrowing for private sector firms as long as they hedge the exchange rate exposure. For a manufacturing firm trading internationally this is sometimes a very efficient funding strategy – to match revenue with financing.

I think for the normal punter – borrowing in foreign currencies to speculate on a financial asset price trajectory, or to buy a home is ridiculous and bound for trouble.

But the basic point is that every reference to trade or current accounts in the Report and the other material accompanying the promotion of the Conference belies an understanding of the role of the external sector and how it interacts with the domestic sector. The understanding we would reach from reading the Report is that exports are a benefit and imports are a cost.

It is, exactly the reverse, of-course. So that sort of backwards reasoning always points back to a neo-liberal macroeconomics and then we are not in progressive territory at all.

The debate soon descends into arguments about acceptable deficit/debt ratios and fancy formulae are brought to bear by the so-called progressives (the deficit doves in this case) and the conservatives. But both camps miss the point completely because they fail to understand how the currency works. So I became worried as I read further.

But then a few paragraphs later I read:

Deficits generate concern across the political spectrum. Already bloated from Bush’s tax cuts and wartime operations, the deficit was pushed to alarming heights by the recession and the urgent recovery spending.

So what are we dealing with here was my thought? We will not build a new economy if we use terms like “bloated” and “alarming heights”. That is neo-liberal talk that has invaded the rhetoric of even the majority of so-called (self-styled) progressives (not!).

The Report then extols the virtues of rebuilding national infrastructure and focusing it on sustainable ways of doing things. I agree with that and the run-down of public infrastructure across the World is one of the greatest examples of neo-liberal myopia. I was doing my PhD in Manchester at the height of Thatcher’s attacks on the public sector.

At one point the sewers collapsed in Manchester due to lack of maintenance. The cost of repair and replacement was much larger than the on-going costs of maintenance. Myopic and stupid.

But then the Report gets to the crunch question. The basic tenet of the lobby is that for the new economy – “it’s important we build one not based on the assets bubbles of the past but on the firm rock of manufacturing.”

They say:

It would be folly to replace our dependence on foreign oil with a dependence on foreign manufacturing … Production was at the heart of our national identity and our national strength. But America’s once-robust system of economic production – the invention, design and manufacture of products – has steadily eroded. Instead of building, we import. Instead of producing, we consume.

They argue that the rising service sector “has not served our country well” (meaning America). I wonder if the Norwegians would say the same thing. I suspect not. The difference of-course is in how the service sector is constructed (public versus private) and what it does (personal care/environmental care services versus selling mobile phones in shopping centres).

So they consider a return to manufacturing to be the mainstay of the rebuilding of America and an industry policy is now urgently required.

In the context of developing an industry policy, the Report poses several interesting questions: Where does the steel for the new rail line come from? Who operates the equipment? Where was it made? Who designed the software? How did they pay for school?

They thus argue for “a strategic collaboration between the private sector and the government to reach our shared national goals.” This would be in the form of new pro-business legislation, direct federal involvement, tax changes to stop production moving offshore; and subsidies to manufacturers to allow them to invest “in a modern infrastructure and providing seed money for research and development in key sectors whose commercial application will come later”.

A manufacturing spokesperson is quoted as saying:

But chalking up the blame to a few bad apples on Wall Street and their risky financial instruments, and responding by simply providing appropriate regulation in the financial services sector, will ultimately be unsatisfying. There are much deeper, structural issues which must be urgently addressed. Otherwise, the absurd positive feedback loop will continue: consumer debt, subsidized Chinese imports, American job loss and factory closures, the growing U.S. current account deficit, burgeoning Chinese currency reserves reinvested in American debt … These will only inflate new bubbles and reinforce our current problems.

So not a firm grasp of MMT there.

But the Report and the Conference raised a lot of questions in my mind.

Is a manufacturing base required to sustain high wages and high productivity and therefore high standards of living. I think not!

Further, do you need to produce things to maintain high employment levels? I think not!

If you can only maintain a strong manufacturing sector through protection who wins out of that? Clearly there are many losers within the nation? Who are they?

A beggar-thy-neighbour approach to world economic interactions is also likely to backfire – who wins and loses out of that? Are these characters really wanting the US to become autarkic?

Further, what is the role of the public sector. Do progressives really want the government to be giving out corporate welfare to manufacturers who are unable to pay sufficient wages given the technology and working conditions expected to compete against low wage nations?

What is the responsibility of post industrial nations to allow the poorer nations to develop in the same way that they did – via industrialisation?

Finally, is trade bad or is only unfair trade bad?

The worry I have is that this so-called progressiveness is not what I call progressive at all. It is still grounded – you pick this up by reading some of the literature supporting the agenda – in a macroeconomics – that is, in my view, at the heart of the problem – they seek to redress.

Further, this so-called progressiveness thinks that selective government handouts to private industry will bring back the glory days of manufacturing. I think not!

I know there are a lot of billy blog readers who are sympathetic with this view though (the need for manufacturing etc). I was having a cup of tea with a friend this morning (early) after we installed a new water tank (my second) at my house (manufactured locally by the way to high standards). I now have 20,000 litre capacity (average family uses 42,000 litres a year (but doesn’t have the urban farm lot to water that we have created here!). So the extra capacity will reduce the probability of us running out and having to rely on the mains supply. They fill up and empty around 3 times a years.

Anyway, my mate was saying that he thought we needed manufacturing for strategic (defence) reasons. That is the old argument for protecting an inefficient sector – you might need it one day – just in case our northern neighbours invade. My view is that we have buckley’s chance of repelling any invaders who can find enough ships to get here. So why even have an army much less a factory system that can make tanks and guns!

The conversation was interesting and so in a future blog I will give a more detailed viewpoint on what I think a progressive position on industry policy might look like – and I don’t think it relies on the presence of a manufacturing sector – in the same way that the Washington conference will be arguing for. It certainly will not involve handouts to private capitalist firms. And it will certainly have a lot of public activity as its mainstay.

So a blog sometime soon about manufacturing. That might get Lefty back commenting!

I was also thinking about this in the light of George Soros setting up his Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), which will be located at the Central European University in Budapest. The INET will apparently “foster research, workshops and curricula that will aim to develop an alternative to the prevailing economic system”. Sounds great – until you see who is involved.

INET’s founding Advisory Board members include Nobel laureates George Akerlof, Sir James Mirrlees, A. Michael Spence and Joseph E Stiglitz, Willem Buiter, Markus K. Brunnermeier, Robert Dugger, Duncan Foley, Thomas Ferguson, Roman Frydman, Ian Goldin, Charles Goodhart, Anatole Kaletsky, John Kay, Axel Leijonhufvud, Perry Mehrling, Y.V Reddy, Ken Rogoff, Jeffrey Sachs, John Shattuck, William R. White and Yu Yongding.

Some of these characters are hostile to modern monetary theory (MMT) and there is not a women in sight.

So while I think some of the things Soros does are excellent – for example – this group of economists will not lead the way to a new future and are anything but progressive macroeconomists.

IMF somewhat circumspect about Asia’s future

As a followup to yesterday’s questioning of the need to start contracting monetary policy, the IMF has released a report – Regional Economic Outlook (REO) for Asia and the Pacific – which suggests that continued economic growth in Asia is from certain.

The IMF REO press release says:

Asia is rebounding rapidly from the depth of the global crisis … [and] … Asia’s growth is forecast to accelerate to 5¾ percent in 2010 from 2¾ percent in 2009, both higher than previously projected … Asia’s fortunes remain closely tied to that of the global economy. The other key driver of Asia’s recovery … has been the region’s rapid and forceful policy response. This reaction was made possible by Asia’s strong initial conditions: fiscal positions were sounder, monetary policies more credible, and corporate and bank balance sheets sturdier than in the past. These conditions have given policymakers the space to cut interest rates sharply and adopt large fiscal packages, helping to sustain overall domestic demand.

The last two sentences are total nonsense of-course, other than perhaps the state of the banking system. There is no valid concept of having more or less fiscal or monetary policy capacity as a result of what your policy settings were yesterday or last year.

It is clearly the case that the required fiscal intervention is path-dependent – so if you had been running budget surpluses for some years (as in Australia) and undermining private saving, then the swing in budget outcomes will be greater than if you had already been running deficits and supporting private saving.

The main problem the IMF foresees is the continued weakness of US property markets. At present, housing is recovering slowly but commercial real estate remains in a state of near collapse. How the exposures in that segment unwind (resolve) is unknown but pain is coming.

The overnight news that the US GDP bounced back to growth (modest at that) may allow the remaining vulnerabilities to work themselves out without provoking a further collapse.

But the IMF clearly believes that it is premature to pronounce an end to the crisis. They are also urging the Asia/Pacific governments to maintain their fiscal stimulus packages and avoid the political pressure to cut them back.

They claim that the fortunes of Asia are still locked into the World economy and trade will remain subdued as consumers in the West maintain their current plans to increase saving and reduce their balance sheet vulnerabilities that arose from the credit binge.

The IMF continues

… overseas demand for Asia’s products will remain subdued, keeping the region’s growth well below the 6 2/3 percent average recorded over the past decade … In this environment, policymakers will face two major challenges … In the near term, they will need to manage a well integrated balancing act, providing support to the economy until the recovery is sufficiently robust and self-sustaining while ensuring that the support does not ignite inflationary pressures or concerns over fiscal sustainability. Over the medium term, policymakers will need to find a new momentum to return to sustained, rapid growth in a new global environment of likely softer G7 demand. In this “new world”, Asia’s longer term growth prospects may be determined by its ability to recalibrate the drivers of growth to allow domestic sources to play a more dynamic role. To be successful, rebalancing will require greater exchange rate flexibility and structural reforms that will allow for a smooth reallocation of resources across the economy.

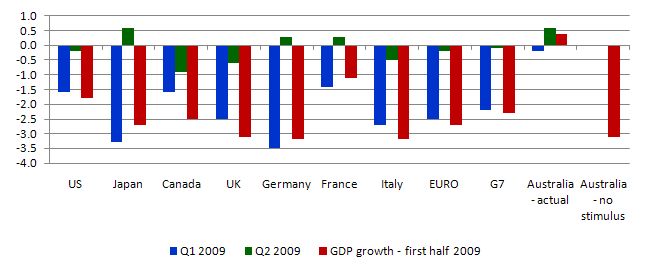

What about Australia? Well for those deficit-haters out there including the federal opposition, who appear to be putting up a good job of being the opposition only to themselves at present (for example, climate change?), the IMF says that the government stimulus packages probably added about 3.5 per cent to GDP in the first six months of 2009.

If that is even remotely correct then, it suggests that the so-called resilience of the Australian economy may be overstated. The IMF also said that exports to China have helped but that would be on top of the 3.5 per cent attributed to the fiscal stimulus packages.

For mainstream economics which is continually publishing so-called research papers which find fiscal multipliers are low to negative 3.5 per cent of GDP in 6 months is a huge real dividend on the fiscal intervention. I will write more about the flaws in the research about fiscal multipliers but suffice to say for now the models used to estimate them are deeply inadequate.

To give you some idea of what the IMF estimates mean, I created the following graph which compares the first half of 2009 GDP outcomes for Australia with the performance of some other nations – and shows what our relative performance would be like without the stimulus (assuming the IMF is right – which I admit is dangerous). However, in this case, I think they are somewhere in the ballpark.

The blue bars are GDP growth for the first-quarter 2009, the green are for the second-quarter (in the spirit of the “green shoots” rhetoric that is everywhere now), and the red columns are for the first half of 2009 in total (simple sum of the two). Note the sum of the two separate quarters is not the same thing as the growth calculated from January-start to June-end, which is what the IMF 3.5 per cent is about. But the difference will be fairly immaterial to the point being made.

If the IMF is correct, then Australia would have been down in the gutters with the other large economies, which in my view, did not have as rapid a fiscal response as we enjoyed in this country.

Digression: colour matters

Here is a comparison of the US Government stimulus versus the Australian Government’s stimulus package advertising billboards (on sites where money is being spent). I am partial to blue so I like the Australian sign – which was taken in the front garden of the local primary school near where I live in Newcastle.

But all governments advertise like this – some call it waste. I call it spending on sign writing and it creates work. The Australian Government was forced to add the usual electoral office information because the Australian Electoral Commission deemed it political advertising.

Digression: Saturday Quiz

Back tomorrow tougher than tough!

I have been reading Billyblog but not commenting on account of my poor sick PC. It has become extremely unreliable but is soon to be replaced with a new model, complete with all whistles and bells.

Bill, you know I agree staunchly with you on nearly everything. But:

“What is the responsibility of post industrial nations to allow the poorer nations to develop in the same way that they did – via industrialisation?

I don’t think poorer nations are developing in the quite same way. Or at least, the implications are different. Did the shifting of rural workers to the factories displace tens of millions of existing workers from employment? As far as I am aware, there was nobody to be displaced as such in those days. Which is why it is not the same thing.

I know this could be completely offset – and SHOULD be – with the job gaurantee. Still, I feel that abandoning the capacity to do certain things for yourself is asking for trouble in the long term. I have to agree with your mate. If we could assure peace by throwing all our weapons into the sea, everybody would have done it long ago. Most of the time, nobody really wants to fight – that’s why weapons are rarely for using. They are for having.

My own life experience has taught me that displaying that you have no capacity to defend yourself does not ensure peace. Quite the opposite. I believe that applies up to the macro level as well.

As for the rest of your blog – excellent as always.

The understanding we would reach from reading the Report is that exports are a benefit and imports are a cost. It is, exactly the reverse, of-course

This was Thatcher’s view as well, in selling off the public goods in order to achieve a short term fiscal boost.

A waiter is not going to be more productive over time, whereas a manufacturer is. To the extent that an increase in consumption comes at the expense of liquidating capital that has increasing returns, and replacing it with capital that has decreasing returns, then this is a net harm, not a net benefit.

What would be the cost of trying to re-establish a domestic machine tool manufacturing sector? Much higher than the cost of replacing a sewer.

The workers understand this, and they intuitively understand that wage arbitrage and de-industrialization reduces their prospects for a good life. You can spray-paint “imports are a net benefit” all over the shuttered factories, and offer $8/hr jobs to the laid off engineers and machinists who were earning $40/hr, but to the degree that any nation has successfully improved living standards, it is because it has shifted its industries from fields with decreasing returns such as cash crops and service sector jobs to fields with increasing returns such as manufacturing. When the U.S. stops being an industrial country and starts being a nation of haircutters and retail clerks, then we will become a subsistence-wage nation, regardless of the current account or the size of the private sector fiscal balance.

The idea that manufacturing is required for increased national/worker wealth is somewhat reminiscent of the physiocrats.

Of course manufacturing increases productivity over time. Lets imagine at some point China has all the global manufacturing capability and there is 1 worker pushing the button making it happen. What is her wage and what does everyone else do to make a living? You might think she makes $20 trillion a year with pay deductions of $19.9+ trillion (and a world central bank to distribute the booty).

Or, everyone else (including the non-manufacturing Chinese workers) have service jobs that provide them sufficient wage to purchase the output of that one productive worker.

Production may create value, but consumption realizes value.

Unfortunately, I believe that even if manufacturing were re-established in the US, the lack of a union culture (destroyed) and the increased “productivity” of employers to suppress unions would end up with manufacturing jobs paying $8/hour.

I don’t know that going back in time using old tactics is the proper strategy here. I realize that some unions are adjusting – not union bashing here, but there is an element of the “good old days” in some of rhetoric.

The solution is to build more public wealth and goods – whether these are assets, products or services. Producing more commodities to circulate in private markets is not going to increase the public’s share of wealth regardless of where the factories are located.

Pebird,

Or, everyone else (including the non-manufacturing Chinese workers) have service jobs that provide them sufficient wage to purchase the output of that one productive worker.

Therein lies the rub. We can export all of our increasing return industries today in exchange for a bit of extra consumption, sure, but what happens when this productive capacity is gone and China no longer wants to trade on terms that allow us to buy that output? It is very hard to get productive capacity back when it is gone — ask Argentina, which used to be a rich nation prior to World War I. This is why each nation should contain sufficient increasing-return industries to allow it have increasing productivity internally, so that button pusher is under the political control of those who can ensure that the goods are distributed to the population. Sell off the button pusher to boost consumption, and you will lose out, long term.

The same goes for developing countries. They can cultivate their own increasing-return industries, protected behind trade barriers, as has every industrial power. The richer powers can send aid in terms of skills, education, and training. When those industries become a bit more mature, then can trade with nations of similar developmental level, eventually graduating up to the majors. When an industry cannot compete — well it is better to have an inefficient industrial sector than to not have one at all. An inefficient industrial sector has the potential to be more productive in the future. A nation of waiters and exporters of cash-crops will never be more productive. That nation has reached its peak standard of living, and the only possible increase is a long slog of trying to acquire more productive capital.

The key is self-reliance, just as with currencies, also with productive capacity.

The fallacy (respectfully submitted) is that manufacturing is an increasing return industry. Perhaps, but to whom?

Manufacturing has increased productivity by such a degree that planned obsolescence was incorporated in the 50’s, duplicative product design (branding) in the 60s-70s, throwaway electronics in the 80-90s, and overproduction of auto, electronics, aircraft, consumer goods in the 21st century.

The increasing return in manufacturing is the ability to produce more quantity with less labor.

Now, the US still has relatively strong capital equipment manufacturing (Caterpillar, machine tools), but there is not a lot of job growth there either, overcapacity and output productivity the reasons.

I don’t dispute your thesis on productive capacity – of course a nation must provide value in excess of their needs, and there is the risk of specialization, so there has to be diversification of industries.

But I don’t want to privilege any industry sector. What provides a nation competitive survival is flexibility and quickness in response to change. How do you get that? Public goods: education, rebuilt cities (livable density for speed of information), modern transit, health care, legal apparatus, research, public technology, etc.

Remember that when investment poured into China, the most recently available capital goods were placed into factories (maybe not in the density that would be in the West due to higher cost labor). If the US rebuilds its manufacturing capability, it will be with the most productive capital equipment available – how many manufacturing jobs can realistically be provided without creating immense overcapacity?

Of course countries should have manufacturing, they should also have agriculture, energy, pharmaceutical, chemical and defense industries and more. And they all do. But how much is really necessary? What is the proper proportion?

I don’t think there is a simple or magic formula – its a constantly moving target. People are self-reliant – in a incredible variety of activities.

You know, from the perspective of the US public the relationship with China “could” have been financed by public spending instead of private debt. There could have been public jobs in a variety of service industries, the public would not now be is such financial trouble.

The paradoxical thing it that it *appears* that way – everyone talks about China “funding” the US debt – but that “debt” was used for Middle Eastern wars, building new surveillance and security capabilities, transfer payments to non-productive private industries and to wealthy private individuals. Why not use the spending capacity to provide opportunities to the people who are moving from manufacturing to service occupations?

By asserting some primacy of manufacturing over service jobs we end up justifying the low wages of service workers – WalMart the largest private employer in the US gets away with low wages and thin benefits – because “anyone can do that job”. What sense of equality and justice and honor of hard work do we have in the US?

It’s a false sense of power the one person pushing the button has; you are correct, they are just waiting to be bought off. Just as trade unions fostered that belief in their members over the poor ‘unproductive’ waiters – go get a meal in a restaurant without waiters – you’ll end up with a hamburger and fries.

The whole lost-manufacturing job theme is a head fake, IMHO.

The fallacy (respectfully submitted) is that manufacturing is an increasing return industry. Perhaps, but to whom?

I mean increasing return in the sense that it allows for the creation of more goods with less effort. The number of people employed are irrelevant, as the political system can allocate those goods as long as the capacity to produce is there.

When you sell off those types of industries because of currency imbalances or other short term reasons, you may find it very difficult to get that productive capacity back. I disagree that we can recover lost productive capacity if we just have enough public goods or are “flexible”. Productive industries require an ecology consisting of institutional knowledge, relationships with other industries, credit-relations and educational institutions. There are network effects. This is an area that is under-researched, as most people treat capital as the single letter K, with some constant factor in front. Perhaps Bill has some good insights here.

Historically, productivity gains have only come as the result of active government led-industrial policies, weather military-industrial complexes or export-industrial complexes. They have never just “arisen” out of flexibility. You cannot just acquire a flourishing aircraft manufacturing sector with good public goods. In the same way, we have an IT sector because of about 40 years of government subsidies prior to it ever making a profit. It didn’t just happen. From Biotech to IT to Aerospace, it was all protected, funded, and promoted by active government policy. The same thing for every western nation, and every developing asian nation. This is not to say that there are not excesses, but “imports are a net benefit” is patently wrong, unless your time horizon is one year, and you are agnostic about the distribution of that income.

That said, I am not advocating that we need full self-reliance. Only that as a nation we have an industrial policy that ensures a sufficient amount of increasing return industries to allow for enough growth. Then, we need a political system that ensures everyone benefits, even though those industries will only employ a few people.

I also believe that when less developed countries compete in an unfettered way with the west, the result is that their increasing return industries are killed off and they are forced into things like cash crops for export. So those countries need protection of their weak industries and competition with nations on a similar development level, together with the ability to export cash crops and receive aid and capital. It is cruel to force them to open their markets in industries that they are trying to develop, as we never did that in our history. As they improve, then they can compete with other nations. This is industry specific. Again, not every nation needs one of everything, but enough increasing industries to have the economy as a whole increase at a suitable level.

In terms of the manufacturing job theme, well there is good data that incomes fall in industries that outsource to countries with lower relative wages, and that incomes rise when we outsource to countries with higher wages. So the effect on wage inequality is pretty solid. How severe the loss of manufacturing capacity is will need to wait until some form of crisis, I guess. But I think much of the excess capacity we have now is fictional. A rapid currency adjustment would be a real shock that will be much more inflationary than the current excess capacity data suggests.

Hello Mr. Mitchel,

While I await your upcoming blog(s) on industrial policy for industrialised countries, I wonder if you could direct me to an analysis of the Australian government’s plan to install fibre optic cable to most homes, from a slant sympathetic to the public interest and public ownership.

Thanks.