I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Macroeconomics get lost in the kitchen cupboard

Today we go into the kitchen cupboard for a lesson in macroeconomics. That is according to the main economics writer of the Sydney Morning Herald, which is published in a city of over 4 million people. The reality is that while we are encouraged to get our heads into the cupboard, all we succeed in doing is further obscuring any understanding at all of how budgets work and the opportunities and capacities of a sovereign government operating within a fiat monetary system. We were really scraping the barrel today!

Also today, intelligent readers had to put up with opinions of the former treasurer who was crowing about the performances of his government. When will he go away?

It was also as if he and the economics writer of the SMH (Ross Gittins) had been out having a cup of tea together such was the similarity and fogginess of their respective articles.

The former (failed) treasurer begins his article with a bushfire analogy. He argues that if you manage the risk ahead of the time by building fire breaks and clearing the undergrowth then the danger will be reduced when the fire season comes. Maybe.

He then generalises that to the current economic situation by saying that:

Over a long time, combustible undergrowth built up in the US financial system – poor credit practices, complex derivatives, off-balance sheet liabilities and lax prudential standards allowed by gaping holes in the regulatory system. The housing bubble collapse ignited the mix.

I agree with that. But the important question is why did that all happen. Why did sovereign governments allow the financial sector to do that? Why did we think that self-regulation would work? The former treasurer belongs to the same club that pushed the world economies into this state – the neo-liberal club.

He goes on to argue that:

Over the course of the decade, both the US and Britain had run large budget deficits. Their national governments carried huge debt. In an attempt to recover from recession, each has undertaken large stimulus spending. Their debt starting point was bad enough; their finish will be even worse.

You might like to read this blog – Some myths about modern monetary theory and its developers to see some historical analysis of US budgets.

The fact is that between 1998 and 2001 the US Government ran increasing surpluses which started to taper off in 2001 as the US economy went into recession on the back of the fiscal drag. During that time, the private sector became more heavily indebted than before as the fiscal drag squeezed liquidity. Further, the surpluses set up the conditions for a major recession in 2001-02 with unemployment rising sharply and the automatic stabilisers pushing the budget back into deficit.

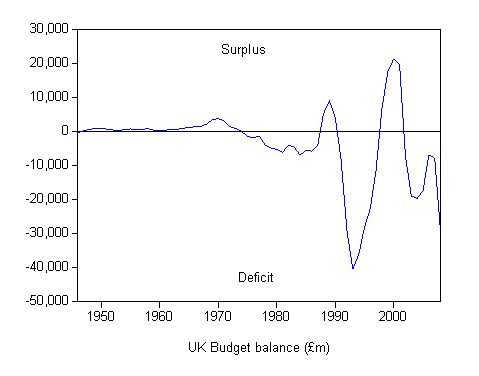

Here is the history of the UK government budget balance (from UK National Statistics) from 1946 to 2008. Again the former treasurer is not quite accurate. The UK ran surpluses from 1998 through to 2001 and left the same sort of legacy that the Clinton surpluses left in the US.

I think it is always better to get our facts straight before we make too many claims. I guess “over the course of the decade” is the opt out clause. It doesn’t exactly mean over the entire decade but the impression is given that the US and UK governments were profligate in their spending and have made the mess messier as a consequence.

But the biggest misconception being pushed is that past deficits (and past debt) somehow makes it harder for a sovereign government to react to a major economic downturn via fiscal policy. That is totally erroneous in an economic sense. It might be that politically it is more difficult but that just reflects the ignorance of the electorate fuelled by miscreant analysts and commentators who fail to understand the nature of the monetary system they are pontificating about.

The former treasurer then claims that:

A country cannot just spend its way out of recession. If it were just a question of spending, the US and Britain would have avoided the downturn. Neither Barack Obama nor Gordon Brown’s government is a slouch in the spending department. The fundamental causes were the combustible mix – the unstable financial system and the housing correction which set it off.

Well a country can spend its way out of a recession – actually, its the only way to get out of it.

Ignoring the complexities of whether we should judge the status of a downturn via the labour market or the product market, a recession is when output growth becomes negative for 2 consecutive quarters. That occurs because aggregate demand falls below the current aggregate output being produced by firms. They react to the growing inventories by laying off labour (or cutting working hours) and reducing production. It spirals downward and we get negative GDP growth.

The only way to get out of the output (spending) gap is to fill it with … spending. That is the whole logic of using fiscal policy as a counter-stabilising measure.

Final spending (aggregate demand) is also a mix of private, foreign and government decisions. Private spending can fall away very quickly and unless there are large “ready-to-roll” public projects available and a will to deploy the necessary public spending, output growth can quickly turn negative. So avoiding a downturn is sometimes rather tricky.

Further, the fiscal reactions of the US and UK governments have hardly been to my taste. The UK government relied heavily on quantitative easing, which I have argued before was an ineffective way to deal with the crisis.

The US government has poured cash into the top-end-of-town while watching consumer spending (and jobs) plummet. The fiscal response has helped the executives get their bonuses back in full but done less for consumer spending overall.

Of-course, the purpose of the former treasurer’s article is to self-congratulate himself for what he sees as a stellar performance while he was in government. But he didn’t need to do that. The Fourth Estate was at it today doing it for him.

Come in Ross Gittins …

I think there is a race on among journalists around the World as to who can misrepresent the macroeconomy the most. The article Give the old blokes a little credit, by Sydney Morning Herald economics writer Ross Gittins today (September 16, 2009) is one of the worst articles I have read in the current period.

In this article, we delve to new depths into the fallacious household-government analogy.

He starts off by noting that he doesn’t “have a problem with high blood pressure … My pressure’s low, better than many my age – but that’s because I always take my pills”. He uses this later to make an analogy with the health of the economy. But as you will see, I have another theory.

He then says that the fiscal and monetary policy stance at present is “working well” but claims you have to look backwards in time for reasons why the economy has not gone deeper into the recession abyss. He says:

… John Howard, Peter Costello and the Liberals are entitled to a lot of the credit for our comparatively comfortable position. In seeking to deny them that credit, Kevin Rudd is being disingenuous and churlish.

For overseas readers, Howard (immediate past Prime Minster and only the second to not only lose government but also his personal seat in Parliament) and Costello (the failed former treasurer who coveted Howard’s job but never had the courage to challenge for it) were the two top ministers in the previous conservative Liberal government. Although there is not much difference between them and the current government led by Prime Minister Rudd.

The point that Gittins wishes to make then follows:

In other words, although our position owes much to the size and speed of the Government’s response to the global crisis – and the Reserve Bank’s – it owes much to the good state we were in when the global financial crisis hit a year ago. And since Rudd had been in office less than a year, the economy’s state was largely the consequence of his predecessors’ policies.

First, he tackles the bank question – why haven’t our banks failed? We do have better regulation than elsewhere and that goes back into history. This is a conservative place. The previous government didn’t invent that.

Further, the current government gave the big-4 banks a public guarantee on their borrowing at the onset of the crisis and they have been merrily reaping profits and pushing interest rates up (as the other non-guaranteed mortgate originators lost market share because they couldn’t access funds as cheaply as the guaranteed banks).

But after dealing with the banks which is a side issue in my view, Gittins then takes us into the kitchen to give us a lesson in macroeconomics:

The Liberals’ other great contribution was to have returned the federal budget to surplus and paid off the federal government’s net debt, which they did to a fair extent using the proceeds from the progressive privatisation of Telstra.

Here it’s important to remember – as the present Opposition seems to have forgotten – the great advantage of returning the budget to surplus and eliminating debt is it leaves you well placed for the next time you need to run up deficits and debt in the interests of stabilising the economy.

The budget is like a set of dinner plates. You wash them and put them away after the last meal so they’re ready for next time. All this was implicit in the Howard government’s stated medium-term objective for budgetary policy, to maintain the budget in balance only on average over the course of the economic cycle. Budget deficits are appropriate when the economy is very weak; budget surpluses are appropriate when it’s strong. On average, the deficits and surpluses should cancel out.

It was because our fiscal (budgetary) affairs were in such good order that there needed to be no hesitation in the decision last October for the Government to spend big in an effort to reduce the downturn in the economy. (Remember, however, the downturn would have pushed the budget into deficit even without any additional spending – that’s how budgets work.)

After reading that absolute nonsense, you just have to wonder what he is on. After all, he opened the article telling us he was taking pills.

Rather than being the exemplar of prudence and responsibility, the federal surpluses between 1996 and 2007 damaged Australia. They undermined public infrastructure development. They restrained public employment and were ruinous to our skill development processes.

They compromised the universities so badly that standards have generally fallen across the sector.

They also squeezed private liquidity and the only way the economy was able to continue growing (and the surpluses repeating) was because the financial engineers loaded the household sector with increasing levels of debt – levels that are dangerous and unsustainable in the medium-term. A significant portion of the nominal wealth that was “created” with this debt is now been destroyed.

Many households are facing negative equity in their homes and declining superannuation balances.

To make matters worse, when Gittins says the previous government “paid off the federal government’s net debt”, as if it a good thing, he fails to recognise that that debt was the private sector’s risk-free wealth holdings and provided regular income streams.

So there was nothing good in that.

What about Telstra (our former public telecommunications monopoly)? Well that is another story that I wouldn’t be crowing about.

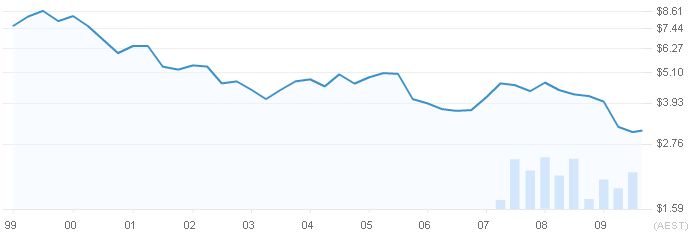

What does the following graph symbolise? The graph symbolises the failure of privatisation in Australia. It is one of many indicators I could assemble across an array of firms/activities which all tell the same story. The time series shows the history of Telstra’s share price since 1999 a few after the previous government began privatising it.

Telstra is in the news today because the current government has finally determined that they will break up the now-privatised monopoly into a wholesale part (running the network) and the retail part (offering competitive services). This should have been done long ago but the previous government that Gittins is so glowing about didn’t have the nerve to do it because the privatisation was a disaster.

How many shareholders would have bought into it if they were told that the company (their investment) would be broken up and face a reduced profit trajectory as a consequence? The breakup will stop the capacity of Telstra to gouge the access prices paid by competitors to its largely monopolised network into homes and businesses.

What about the float in the first place? Initially, the T1 float in 1997 was sold out at $3.60 a share. The T2 tranche was released into the booming dotcom market, and buyers, under constant urging from the federal government of the day, paid $7.80 a share. Soon after, by June 1999, the high was achieved at $8.66 and the neo-liberals were announcing that the float was a huge success.

Remember all that rubbish about the end of the classes (capital and labour) – every home was becoming a capitalist! This ideological trash was pushed across the airwaves and in the written media constantly at the time. Until things went sour that is.

My constant reaction at the time was “why pay for something that I had already own”. I did not buy any Telstra shares!

Then the whole deal turned sour. As is now well known the price crashed not so long after the peak price was reached and the company, mis-managed in the extreme by a sequence of corporate nobodies, failed to enjoy any of the benefits of the strong share market that was to follow.

By then, the government had already fully privatised the company – well sort of – as a consequence of the T3 sale which sold shares at $3.30. I say sort of because the Future Fund bought a lot of this issue and that is just the government in disguise. Readers might like to read this blog – The Future Fund scandal to see how mislead we have been about the Future Fund.

Anyway, back in Telstra land, as a private company it still maintained, by and large, monopoly over the copper wire network into houses and offices, and like all monopolies sought to extract as much profit as it could from this arrangement. It charged ridiculous access prices to all and sundry who the government had encouraged to create a competitive environment in the retail telephone and information services market.

Consumers were dudded by this and only a chimera of competition emerged. Further, the company failed to invest in upgrades of the broadband network and Australia is left behind other nations in having expensive and slow network access.

Now the government is going to order the break up of the company’s operations into wholesale and retail arms which has already seen its prices fall overnight.

So a big success story is Telstra. Not!

Back to macroeconomics.

The claim that “the great advantage of returning the budget to surplus and eliminating debt is it leaves you well placed for the next time you need to run up deficits and debt in the interests of stabilising the economy” is just plain false. The capacity of a national government which issues its own currency to net spend today is neither diminished or enhanced by what it did yesterday or last year or whenever.

A sovereign government can net spend whenever it wants as long as there are things for sale that it can buy.

The only constraint that a past deficit might impose on the government today is if those past initiatives had pushed the economy up to the real capacity limit. Then any further nominal spending growth will be inflationary. But then why would a government want to push the economy past that point anyway?

And, that situation is not evenly remotely like the current environment.

Then we get into the kitchen with the dinner plates and learn from Ross that “The budget is like a set of dinner plates. You wash them and put them away after the last meal so they’re ready for next time.”

I collapsed laughing at this analogy – a deeper appeal to the intuitive wisdom of the householder so they can truly understand the nature of a public fiscal balance.

The dinner plates represent a stock, Ross! Government spending and taxation are flows. On a daily basis, we might take a snapshot of the net result of these flows and that is called the budget balance. But any balance is here today gone tomorrow.

But more importantly, the stock of dinner plates sits in the cupboard and represents a surplus of china. The corresponding budget surplus cannot be found anywhere other than in the accounting records of the government. There is no storage of “money” that is available for later use.

Some analysts call sovereign funds (such as the Future Fund) such a storage. They are not. They represent government spending on speculative financial assets instead of public goods, education, hospitals, employment and whatever else the government might have purchased with the spending.

Gittins then rehearses the standard mainstream mantra about budgets – that it is prudent “to maintain the budget in balance only on average over the course of the economic cycle. Budget deficits are appropriate when the economy is very weak; budget surpluses are appropriate when it’s strong. On average, the deficits and surpluses should cancel out.”

As I have said often, this amounts to saying that the non-government sector net saving balances out to zero over the business cycle. With a country like Australia in current account deficit more or less continually, this means that the private sector will be permanently in debt.

That could never be a sustainable and responsible strategy. The private sector (households) typically desire to save a fraction of their disposable income in aggregate. So a strategy to push the budget into surplus will usually be thwarted by income adjustments as the fiscal drag comes up against the saving desire.

Gittins, of-course, couldn’t finish such an article without a venture into the debt-hysteria angle. He says:

By contrast, the Americans and most of the Europeans had big annual budget deficits and high levels of accumulated debt when the crisis hit. That didn’t stop them spending heavily to stimulate their economies as well as to bail out their banks. Needs must when the devil drives. But this is why there’s now so much worry about the huge levels of debt the developed world is acquiring. The need to service and slowly pay it down will be a major constraint on the world economy for many years.

Exactly what is the reason for the “so much worry”. It is just an assertion – the “dogma chorus” rehearses its line on a daily basis in case they forget their lines. Nothing is explained here.

Is the fear inflation? Maybe, if spending (including debt servicing) pushes the economy up against the inflation barrier. But things are so bleak at present that these economies have so much “spending” capacity left that inflation should not be a concern.

How about Japan in the late 1990s Ross? They had what Gittins would call crippling levels of debt but kept expanding fiscal policy as the private sector increased their saving desire and finally the former won out against the latter and the economy resumed reasonable growth in the early 2000s. The debt didn’t stop that happening at all.

Conclusion

Must be time to start another blog … like raising flowers in ten simple steps. At least, I could escape the drivel that passes for economic analysis these days.

Dear Bill,

I just love the way you let ’em have it – all guns blazing! It is so entertaining yet so sad that the earth remains flat.

Just this evening in the 7.30 report on the ABC-TV there was a segment on the recent cutting of the Federal Government subsidy for renewable energy in the bush – because the money had run out!

Bill,

I agree a govt can spend its way out of recession, but I do not believe it is the only way. Tax cuts for consumers can be just as effective. The second qtr of 2007 the US gave a tax rebate ($600/300) and that qtr saw a spike in gdp. A tax cut of course is the same thing as a rebate except instead of taxing and returning you let the taxpayer keep the money in the first place. Yes the govt needs to spend on infrastructure and education, but I would prefer a tax cut over spending money on bridges to nowhere.

Dear markg

Tax cuts may be expansionary but clearly less so than government spending. If in the late 1990s, the Japanese government had have tried to lower taxes as their only vehicle to revive the economy then saving would have risen and the economy would have plunged further into recession.

A mix of the two (spending, tax relief) is often a good strategy but it also depends on the balance of private and public spending that you want in the overall economy.

Further, the “bridges to nowhere” reference always seems to crop up when we discuss the differential spending capacities and virtues of the private and public sectors. A lot of private spending is on “junk” and I see no end of high quality, high outcome things for the public sector to spend on.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

Let’s not forget how Smirky Pete Costello sold off two-thirds of Australias gold reserves in 1997 at a price of $330 an ounce. I’d love to hear Gittins explain how pissing $5billion away like that is in anyway sound economic management?

Cheers, Alan

It strikes me that the conservative opposition in the major economies like to push the effect of monetary policy as the real driver for economic recovery, highlighting less so the effect of deficit spending/tax breaks. This is because the latter represents a ‘problem’ that said opposition feel they would need to ‘tackle’ if/when they get voted in. This goes back to the msm erroneously likening govt. finances to houshold finances. Highlighting monetary policy over fiscal is also important for them as their criticism of the govt. in power is about the deficits being run.

But back to monetary policy, would it not be fair to actually say that it has helped as part of the recovereh process. I know you yourself have said that interest rates need to be kept low in such circumstances, and they do say rate cuts do tend to have a lagging impact. So part of the receovery indicators from the last quarter could be partly the result of IR decisions taken several months ago ? Plus IR cuts and the effect on houshold budgets [this much touted desire to save] cannot be denied, much of the UK housholders are on bank base rate trackers, and have seen the interest portion of their mortgage payments reduce dramatically – so even if banks aren’t ‘passing on’ rate cuts in full to new customers existing mortgage borrowers have benefted directly from central bank base rate policy. This has given them extra disposable income or put them in a position to pay down mortgage debt. And when they come off these base rate trackers the lenders standard variable rate is low enough not to cripple them with unreasonable mortgage repayments. This to me is monetary policy in action, not unlike following the 2001-recession.

Plus, the banks seem to be buoyed by the effects of quantitative easing [imagined or otherwise] they are after all big cheerleaders, plus the alphabet soup of schemes by govt. and central banks to save the financial system. Surely this has ultimately led to the return of confidence and boosting of banking sector share prices. Even the ones that required bailout with large govt. equity stakes. Can we be sure that monetary policy hasn’t contributed as much as fiscal policy to the recovery story ?

Dear Tricky

Good points.

I am not denying that monetary policy is useless. The problem is that the utility of it hasn’t been categorically established using credible research techniques and from a logical (theoretical) basis there are reasons to suspect its effectiveness. I am referring here to the two sides of the transaction issue – the creditors lose and the debtors win, those on fixed incomes (retirees) lose, etc. How this nets out is unclear and you cannot simply assume creditors have lower propensities to consume than debtors therefore it will be expansionary. It might be but then we are not sure.

The other problem is that any impacts will be lagged as you say and so tracing when the impact appears and how long it lasts etc is also very difficult.

Having said that, I have said that for those carrying very high debt burdens at present, the lower interest rates (in Australia) have eased the possibility that the falling hours of work will cause defaults. That is why I am arguing against any rate increases at present (and always actually). So I agree 100 per cent with you on that one – here and in the UK, and probably elsewhere.

I am not sure that bailouts and credit lines and currency swaps have done much for bank lending though. Maybe. How would we tell? I think they have transferred monumental volumes of public monies into the hands of the rich but done little to boost confidence and employment. The banks in the UK, for example, are still not lending very freely. Why not? Perhaps because the labour market is still in free fall. My prior is that fiscal policy is more potent in restoring confidence. How would I tell that? Good question. Logic tells me that because it is more direct and can be targetted. Empirically, it is very hard to establish that.

But overall I don’t think we are that far apart in our views on this specific issue.

best wishes

bill

the thing about the bank bailouts has been that it has been or rather will turn out to be a monumental win for govt. in the case where there is significant equity stakes in major banks. These preference shares were purchased when there was a belief that we were heading over a cliff.

the govt. would have known that they had the means to address a liquidity crisis [for this was a liquidity crisis NOT a solvency crisis as various commentators wrongly concluded] so long as there was a global effort to coordinate action, and so would have known from the start they were going to make big profits [eventually] from any undertaking to support the banks by taking large stakes at rock bottom prices, and by charging for participation in asset protection schemes following the problems in the wholesale funding markets that affected banks with big exposure to the securitized model.

i don’t understand this concept of the bailouts enriching the bankers specifically, unless we are talking about those who hedged on a startling recovery in stocks and various asset classes……but then i think we call these folk speculators. Govt. intervention has been a once in a lifetime opportunity for speculators to cash in on a rebound following two lows at the tailend of 2008 and Mar 2009, and all that cash and old money has dashed for assets as the govt. devalues savings and cash holdings, but we’ve always known that, as you’ve put it, debtors win. Cash in a bank is an albatross around one’s neck in a debt based system and where central bank action attempts to divert cash into assets.

Back to the banks, there were some banks in the US who would rather not have taken any TARP money, were sufficiently confident in raising additional capital themselves, but would have possibly been pressurised to do so. They then repaid this money in double quick time without much fuss.

All the policy response proved was that the banking sector is extremely competent at making money when the right conditions are created. Govt doesn’t want to tell the banks how to do their business, they’d certainly rather return nationalised banks into private hands and see a return on any investments made using public money. And that will happen eventually, and it appears everyone has already forgotten what the fuss was about as we talk of a stock market and financial sector recovery.

I say the main players will get what they want, more fool us the genral taxpaying public for blaming bankers squarely when we should be blaming govt. for abusing it’s power as monopoly issuer of currency, via the diabolical actions of the main central banks over the last decade, not to mention govt. not having the inclination to regulate correctly banking activity during a bubble that central bnaks created via a govt. mandate.

Yes, some actions of the banking sector were irresponsible, but govt. create the conditoins for any irresponsible risk taking. That’s my view, i’m open to being convinced otherwise.