The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Exploring the essence of MMT – the Job Guarantee – Part 2

This is Part 2 of an irregular series I am writing on some of the complexities of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) that are often overlooked by those who rely on reading airport-style books or Op Eds on the topic. In – Exploring the essence of MMT – Part 1 (March 29, 2022) – I dealt with some conceptual issues about values and theory. Today, I am considering the way to think about the – Job Guarantee – within the MMT framework. The Job Guarantee is at the centre of MMT because it contains an insight that is missing from the mainstream economics – the concept of spending on a price rule. This insight leads to the conclusion that the price level is determined by what the monopoly issuer of the fiat currency – the government is prepared to pay for goods and services. This, in turn, means that the Job Guarantee goes well beyond being a job creation program and constitutes within MMT a comprehensive macroeconomic stability framework – where the so-called trade-off between inflation and unemployment (Phillips Curve) is eliminated. However, while in the real world, complexity enters the scene and we need to be aware of the nuances so that we do not fall into the trap of thinking of the Job Guarantee as an inflation killer.

Origins of the Job Guarantee

In this blog post – The provenance of the Job Guarantee concept in MMT (April 20, 2020) – I traced the origins of the Job Guarantee within the MMT tradition.

I noted that as an agricultural economics student in 1978, I determined that the tradition of using commodity buffer stock in agricultural markets to achieve price stability could be applied to the labour market and alter the way we conceive the Phillips curve.

My motivation was the Australian Wool Reserve Price Scheme, introduced by the Australian government in November 1970.

It was a typical commodity storage scheme and required the government to maintain a wool buffer stock to stabilise wool prices in the face of market fluctuations.

The same principle operates for a Job Guarantee – the government operates a buffer stock of jobs to absorb workers who are unable to find employment in the non-government sector.

The pool expands (declines) when non-government sector activity declines (expands). Workers would also be able to choose the hours they desire up to full-time, which would significantly reduce time-based underemployment.

The unconditional job offer would be at a socially-inclusive wage, which would be set at the bottom of the wage distribution and become the wage floor for the economy.

At the point of introduction, government could set the wage above the prevailing minimum wage to facilitate an industry policy function (that is, shift resources out of low productivity, high cost private firms).

The novelty of the Job Guarantee is that the government purchases labour off the ‘bottom’ of the labour market rather than competing at market prices.

By definition, the unemployed have zero bid in the non-government sector for their services.

As an aside, many people have written to me claiming that if the – Australian Wool Reserve Price Scheme – which ran for 31 years between 1970 and 2001, was the model I used to design a Job Guarantee then it would fail as the wool scheme failed.

The problem with these criticisms is that they usually do not understand why the wool scheme failed.

All they know is that it was discontinued and they may have heard some negative things about it.

The facts are clear and lead us to conclude that the failure of the wool scheme, in no way compromises the integrity or the sustainability of the Job Guarantee mechanism.

I will write another day about the reasons that led to the collapse of the wool scheme (greed from farmers and neoliberal outsourcing by government etc). But it is important to note that those reasons are not applicable to a Job Guarantee scheme.

The Phillips Curve and MMT

I wrote about this topic in this blog post – Flattening the curve – the Phillips curve that is (April 7, 2020).

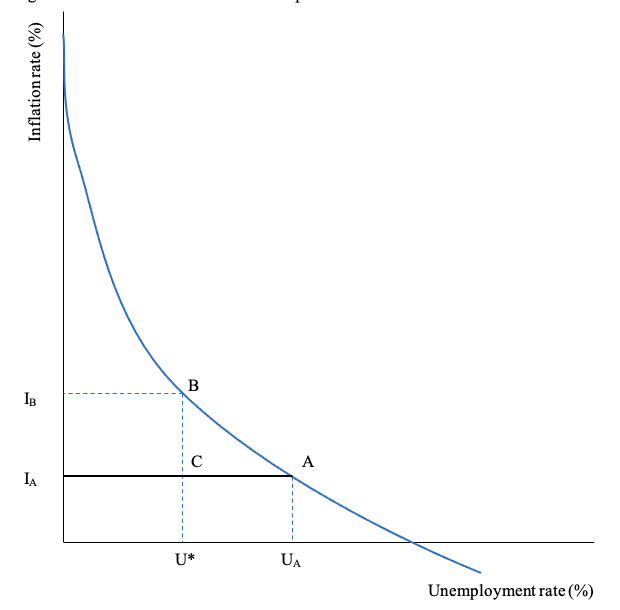

The following diagram captures the traditional Phillips curve and the way the Job Guarantee alters the trade-off.

We begin with an unemployment rate at UA and an inflation rate of IA.

The full employment unemployment rate is U*, which defines frictional unemployment.

The difference between U* and UA is what we term involuntary unemployment and serves an inflation-suppression force.

Why?

The unemployment buffer stock disciplines wage demands by workers (who fear they will be next to join the unemployment pool) and also reduces the incentive of corporations to raise prices for fear in a weakening market they will lose market share to competitors.

In the traditional Phillips Curve world there is thus a trade-off between unemployment and inflation along the blue curve.

There was a lot of discussion in the 1960s and 1970s about how steep the trade-off was. The flatter the curve, the greater the gains in reducing the unemployment rate for a given inflation rise.

Empirical studies of the trade-off revealed the curve was also unstable – it moved around – which made it difficult to deploy as a policy vehicle.

In 2008, we published a research paper – Labour underutilisation and the Phillips Curve (the link is to a working paper version as the published paper is behind a paywall), which showed how the relationship between inflation and unemployment had waned in the 1990s and that the real trade-off was between broad labour underutilisation and inflation (the former including underemployment).

Anyway, referring to the diagram,

Accordingly, if the government sought to eliminate involuntary unemployment through generalised fiscal expansion then the economy would move up the curve to B with inflation rising to IB.

However, Milton Friedman and his Monetarists claimed that there would be no guarantee that inflation would be stable at that level.

When the concept of a Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment (NAIRU) was introduced into the literature by the Monetarists, it was argued that wage and price bargaining forces (unions, firms) would build the higher inflation rate at B into their expectations and resulting behaviour.

As a result, they would demand higher nominal wages and price-setters would push up prices further, irrespective of the state of the labour market.

This would result in this framework with the Phillips Curve moving out undermining the trade-off.

Mainstream economists came to believe that there was only one unemployment rate where inflation would stabilise and expected inflation would equal actual inflation – the so-called ‘natural rate’.

It was asserted that the government could not use fiscal policy to alter that rate and so any attempts to reduce the unemployment rate below it using fiscal expansion would just result in accelerating inflation and eventually (through the expectations movements) the unemployment would be reestablished at the NAIRU (which was the ‘natural rate’) at a higher systemic inflation rate.

However, whether that happens or not is not germane to the following discussion.

A Job Guarantee would provide jobs to (U* – UA) workers.

The improved labour market prospects would no doubt attract additional workers back into the labour force (hidden unemployment) who would be likely prefer the Job Guarantee to remaining without an income.

As a result, the economy would move from A to C instead of A to B as the government fights the inflationary pressures.

In other words, the introduction of the Job Guarantee flattens the Phillips Curve.

The macroeconomic opportunities facing the government are not dictated by a perceived unemployment and inflation trade-off which might be unstable (as in a NAIRU world).

Full employment and price stability can be simultaneously achieved.

The steeper the original Phillips curve, the smaller will the required increase in the Job Guarantee pool be to stabilise inflation at some desired level.

Now the distance A-C reflects private employment losses being the workers that are available to work in the private sector but who are employed in the Job Guarantee.

Government would clearly aim to minimise the Job Guarantee pool, while still allowing for higher levels of non-Job Guarantee employment to be sustained with stable inflation.

Initiatives that may reduce the size of the pool, include public education to stimulate skill development and engender high productivity growth; institutionalised wage setting processes where productivity growth is shared equitably across all income claimants, and restrictions on anti-competitive cartels which should reduce pressures for profit margin push.

So what is complicated about that?

Plenty.

First, recall that I saw the employment buffer stock approach as being superior to using unemployment as a disciplinary force against inflation at a time (late 1970s) when governments, under pressure from mainstream economists, were abandoning their Post War commitment to sustaining full employment because they thought it was inflationary.

Inflation was high at the time and governments were pursuing policy settings that had pushed up unemployment rates and the Post War consensus had crumbled.

The fact they also bought the line that fiscal policy should not try to reduce the unemployment rate and was an ineffective way to manage inflation spawned the reliance on monetary policy and tolerated elevated levels of mass unemployment.

As a postgraduate student, I wanted to devote my research work to coming up with an alternative approach that did not require large pools of unemployment to sustain price stability.

Hence the employment buffer stock approach.

But be clear about it.

A Job Guarantee works by the government creating unemployment in the non-government sector which is undergoing inflationary pressures, and, transferring the workers into the Job Guarantee pool, which is a fixed price job offer.

The transfer occurs through tightening fiscal and monetary policy settings, which we now refer to in summary as ‘austerity’.

In this context, the goal should be to keep the Job Guarantee pool as small as possible.

Yes, in better times, the Job Guarantee pool would still be occupied by the most disadvantaged workers who would otherwise count among the long-term unemployed.

But its primary purpose is to stabilise inflationary pressures without creating mass unemployment by creating the transfer of workers from the inflating sector to the fixed price sector.

Tightening aggregate policy settings to stifle non-government spending creates unemployment under a NAIRU approach.

Under a Job Guarantee, the transfer of workers, at some point, disciplines the distributional conflict driving the inflation.

The Job Guarantee generates ‘loose’ full employment because skill-based underemployment would remain.

The adoption of the costly NAIRU approach reflects the fact that current fiscal policy practice is based on a flawed understanding of the capacity of the currency-issuing government.

Claims that governments are financially constrained bias fiscal policy towards surplus creation.

As a result, governments spend on a quantity rule, which means they allocate $x, guided by what they think is politically acceptable.

What defines political acceptability depends on a range of factors, including the economic literacy of the voters.

The problem is that $x may not bear any relation to what is required to address the non-government spending gap arising from the private desire to save and/or spending drains via external deficits.

As a consequence, mass unemployment persists at elevated levels, which describes the history in most nations over the last 3-4 decades.

Once we appreciate that the fiscal space available to government is limited only by the real resource availability rather than any erroneous financial constraints then we can adopt policies such as the Job Guarantee.

Accordingly, government spending would follow a price rule, by providing an unconditional job offer at a fixed Job Guarantee wage and taking on whatever labour is forthcoming at that price.

It is this insight that points to the statement that in MMT, the government sets the price level by what it is prepared to pay.

Second, so with inflation now, does this mean that the Job Guarantee is the way to combat it?

No!

Why?

Obviously, if the government drives the Job Guarantee pool up, eventually the joblessness in the non-government sector will end any inflationary episode.

But this is a costly approach with the virtue that it is the least costly approach relative to creating mass unemployment.

It still requires workers be transferred to the fixed pay Job Guarantee pool by the government cutting aggregate spending in the economy.

What you should understand is not that the government sets the price level at all times by what it is prepared to pay, but, rather, that this capacity is a ‘conditioning’ force around which other influences interact.

We also need to understand that the scenario I outlined above – the transfer principle – while damaging, is less so if the inflationary pressures are arising from the demand-side – expansion of nominal spending against a steadily growing supply-side (productive capacity).

If the inflationary pressures arise from supply-side factors, as in the current episode, then the damage is greater if we want to use the capacity of the government to influence aggregate spending as the solution to the inflation.

Think about that for a moment.

The pandemic arrives at a time when inflation is low, which means that nominal spending growth is more or less in tune with the growth in productive capacity (supply).

Then factories close, workers get sick, shipping and truck transport becomes severely disrupted, workers are restricted by government in their movements, etc – and so the supply-side contracts for the time these disruptions are in force.

Also the pattern of spending shifts towards goods (as workers are in lockdown etc) and away from services (as cafes, etc are forced to close), so there are also intensification of sectoral imbalances at work.

Inflationary pressures rise even though total nominal spending might be below where it was at the beginning of the pandemic.

Yes, the government could use the ‘transfer principle’ and cut aggregate spending, withdraw stimulus support to workers, and the like and eventually total spending in the economy would fall to the level consistent with the supply-chain constraints.

And that would eventually make things so bad that shipping agents would stop hiking prices etc.

We would stop the inflation, increase the Job Guarantee pool substantially, and make matters worse.

If it was a demand-side event, cutting the excessive spending would for a time create higher unemployment (or more workers flowing in the Job Guarantee if it was in place).

But the extent of the cuts would take the economy back to a higher supply level than we have seen during the pandemic.

The point is that there are other influences on the price level operating here that can persist for lengthy periods and the fact that the government can ultimately discipline those influences doesn’t alter the fact that doing so involves damage under certain circumstances.

Then introduce cartel behaviour and wars

These become additional real world influences on the trajectory of the price level, which can operate quite separately from the monopoly currency-issuing capacity of the government.

Yes, eventually OPEC will stop hiking prices if unemployment becomes so severe that people stop driving cars.

We have seen that in the past.

But until that point, the cartel works as a separate influence on the inflationary process and any attempts by government to assert the discipline of ‘spending on a price rule’ will require huge increases in the Job Guarantee pool.

The question focuses on whether the relative costs of leaving inflationary temporarily high versus creating recession and stagflation.

And the Russian invasion at present is another chaotic factor entering the supply-side.

The existence of a Job Guarantee doesn’t alter that fact.

Conclusion

In the real world then, there are many influences on the price level and a full understanding of MMT requires us to recognise them and how they interact and the way in which government policy can militate against them.

It is not just a case of having a Job Guarantee in place.

Any attempt to stifle inflationary pressures using demand-side policy (austerity), which would invoke the ‘transfer principle’ will be costly – and the cost in terms of lost incomes and all the rest of the problems that accompany austerity could be massive in the case of an entrenched supply-side event.

The Job Guarantee is just a better framework than relying on unemployment.

But triggering increases in the Job Guarantee pool should not be the first thing a government does when confronted with rising price pressures.

Note also: I haven’t talked at all about the impact administrative pricing decisions (indexation arrangements, user cost charges, etc) play.

It may be the most effective way to deal, for example, with price gouging from OPEC is to make public transport more available and free of charge.

That will divert spending from petrol usage to trains etc and achieve the same sort of demand effects on OPEC member income as a generalised austerity purge, without the concomitant rise in mass unemployment.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I remember Patrick Minford in the 80s saying that there was no involuntary unemployment – workers just need to reduce their wage demands and someone will employ them.

He’s still around.

Can we talk of labour and capital in the same way we did in the 1970’s?

In the deindustrialized west, Labour was exposed to all sort of abuses, stemming from deregulation of the labor market.

Do you remember the truck drivers deficit in the UK only a few months ago? It wasn’t because drivers suddendly died in droves.

It was because employers wanted uber-like contrats with drivers, carrying them to serfdom.

Young people in the west finish school and don’t know what to do. There’s almost nothing to do. Good paying jobs are for the elites. There’s only disposable jobs available.

So, the neoliberals are saying: this is just like in the 1970 and we need to cut wages, and so we’ll start a major crisis.

The trickle down, trickles up.

The vicious cycle has to be torn down.

A job guarantee is a way to go in the right direction. It might not be perfect, but it’s the best we can manage to get right now, as we have to move from a heavy fossil fuel dependent society to a ever greener way of life.

We need to recapture the State.

As we can see right now, the status quo has only one answer to all troubles: drill more.

We have to drill less.

If the Russians can’t sell their oil, that’s a good thing.

Unfortunately, the EU just needs more and more oil and natural gas.

We won’t go anywhere we this bunch in charge.

This is how I came to the conclusion that we should have buffer stock price controls on all strategic assets.

The following extract from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/apr/06/climate-scientists-are-desperate-were-crying-begging-and-getting-arrested, I see as applying mutatis mutandis to the trajectory for expanding the acceptance of Modern Monetary Theory as being the way of understanding money, banking and economics and not as taught and promoted by neoclassical economists and their fellow travelers:

“I hate being the Cassandra. I’d rather just be with my family and do science. But I feel morally compelled to sound the alarm. By the time I switched from astrophysics into Earth science in 2012, I’d realized that facts alone were not persuading world leaders to take action. So I explored other ways to create social change, all the while becoming increasingly concerned. I joined Citizens’ Climate Lobby. I reduced my own emissions by 90% and wrote a book about how this turned out to be satisfying, fun, and connecting. I gave up flying, started a website to help encourage others, and organized colleagues to pressure the American Geophysical Union to reduce academic flying. I helped organize FridaysForFuture in the US. I co-founded a popular climate app and started the first ad agency for the Earth. I spoke at climate rallies, city council meetings, and local libraries and churches. I wrote article after article, open letter after open letter. I gave hundreds of interviews, always with authenticity, solid facts, and an openness to showing vulnerability. I’ve encouraged and supported countless climate activists and young people behind the scenes. And this was all on my personal time and at no small risk to my scientific career.

Nothing has worked.”

The above well states the problem for MMT but how to achieve its acceptance as the way it is without having to live through one death at a time to get there. The existential crisis that confronts us all doesn’t have anymore time to wait for adoption of a solution if humans and current lifeforms on the planet are to have an equable future. We are being bombarded by one crisis after another with barely breathing space in between. I was hoping that the pandemic might have been “it” for the wake-up with the “magical” fiscal power of the state fully on view to expose all of those with a vested interest in the orthodoxy. Silly me.

Will we have to await pitchforks in the street, by which time it will be “game over” and into Mad Max territory?

I’ll risk an attempt to modulate Bill’s demure view of the JG. It does not have to be a terribly bad cost if used as counter-cyclical stabilizer. People can actually experience improved standard of living on less income, in many ways: less rat race anxiety (so healthcare savings), less bullsh*t jobs (so less spirtitual violence), more family time, still enough income to live decently. Maybe on a JG income you are not saving too much, or guzzling as much boutique beer, but then MMT would say we aught to be paying pensioners decent incomes too, so there is no excessive and incessant need to save like a Scrooge.

I mean to say, no MMT’er is saying the JG work should not be meaningful and enriching in many other ways other than financially.

The JG is much more than wool buffer stock price stabilization. It has implications for human dignity that cannot be measured by monetary pricing. Do we constantly have to go back, for the pedants, and look at the anemic Jefes y Jefas, which yet had amazing benefits even when so anemic?

How much will a Job Guarantee cost UK in £s max in 2023. I am convincing politicain but insist ‘pay for’