It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Brexit is delivering better pay for British workers (on average)

I find it amusing when some self-styled ‘progressive’ commentator, usually writing in the UK Guardian newspaper, bemoans Brexit and points to claims by business that there is a shortage of workers. The ‘shortage’, of course, is results from not being able to access unlimited supplies of cheap foreign workers as easily as before. When I see a shortage of workers, I celebrate, because it means employers will have to break out of their keep wages growth low mentality to attract labour; that they will have to offer adequate skills training to ensure the workers can do the work required; and, that unemployment will be driven as low as can be. What is not good about that? Brexit has done a lot of things, one of them being to provide the British working class to arrest the degradation in their labour market conditions that neoliberalism has wrought in a context of plenty of low wage labour always being in surplus. A similar thing will come from the pandemic in Australia where our external border has been shut for nearly 18 months now.

On August 6, 2021, KPMG and REC (the Recruitment & Employment Confederation) published the latest – KPMG and REC, UK Report on Jobs – which revealed that:

Recruitment activity continued to rise sharply across the UK at the start of the third quarter … Permanent staff appointments and temp billings both rose at near-record rates, while growth of demand for staff hit a fresh series high as COVID-19 restrictions eased further and economic activity continued to pick up.

However, the availability of candidates continued to decline rapidly in July, driven by concerns over job security due to the pandemic, a lack of European workers due to Brexit, and a generally low unemployment rate. As a result, pay pressures intensified, with starting salaries rising at the fastest rate in the survey history, and temp pay inflation also accelerating notably on the month.

The Report said that:

1. “the rate of salary inflation was the sharpest seen in nearly 24 years of data collection”.

2. “an unprecedented rise in demand for staff” – well not really, just since the late 1990s.

There have been similar statements issued by employer and industry groups, such as the British Chambers of Commerce.

All bleating that Britain hasn’t got enough skilled workers.

Well, that just tells me that they need to train more workers given that last time I looked (a minute ago), there were more than 1.6 million who were unemployed.

There are also reports that “Employment experts believe people are being put off from work in certain sectors that have developed reputations for low pay and poor conditions in recent years” (Source).

So the cure is obvious – offer better training opportunities to the available workforce and better wages to induce the workers to invest the time in the training.

Pretty simple.

Brexit is done.

There are other reports about wage inflation in the UK becoming a problem and another negative from Brexit.

So this is the ‘market’ working.

The Office of National Statistics published the latest wage data – Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: August 2021 (August 17, 2021) – which shows that:

1. “Growth in average total pay (including bonuses) was 8.8% and regular pay (excluding bonuses) was 7.4% among employees for the three months April to June 2021 …”

2. “… since this growth is affected by compositional and base effects, interpretation should be taken with caution.”

I will come back to point 2 soon.

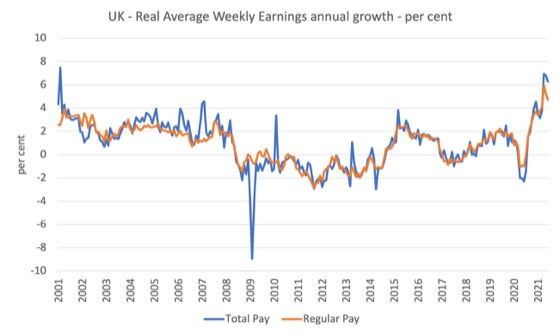

The following graph shows the annual growth in real (adjusted for inflation) average weekly earnings from January 2001 to June 2021 for Total Pay (which includes bonuses) and Regular Pay (which excludes bonuses).

The most recent rise looks dramatic.

But back to point 2.

The ONS does offer a warning in this blog post (May 19, 2021) – Beware Base Effects – for those who seize on month-to-month, or quarter-to-quarter results and think they are new trends.

But, this caution also applies to use of annual or longer-term data, when the base year one is using to compute growth is an abnormal or outlying observation.

As they note:

… it’s important to remember that we have just passed the first anniversary of the pandemic … the statistical effects of that landmark need to unravel before the real the path of inflation and other economic statistics becomes clear.

In other words, if, for example, retail sales had slumped by 20 per cent (because of the pandemic) then a year later any growth will look somewhat larger than is the historic norm because the ‘base’ of the growth calculation was historically very low.

See also this ONS blog post (July 15, 2021) – Far from average: How COVID-19 has impacted the Average Weekly Earnings data

– which explains the ‘compositional’ impacts on the average.

We learn that:

During the pandemic, we saw lower-paid people at greater risk of losing their jobs. Fewer lower-paid people in the workforce increased average earnings for those who remained in work.

Imagine the economy has two sectors, one paying $1000 a week to its 2 workers and the other paying $500 per week to its 2 workers.

The average weekly earnings would be $750 per week.

Now, say the low-wage sector shed a worker, then the average weekly earnings would be $833.30, a rise of 11.1 per cent, event though no individual worker was being paid any more per week.

That is an illustration of compositional effects.

ONS estimated that in June 2021 “the headline regular earnings growth rate is 6.6%”.

Taking into account the base and compositional effects, ONS indicated that:

… the base effect would reduce the headline rate by between 1.8 and 3.0 percentage points based on the two methods set out above. In addition, the compositional effect we estimate at 0.4 percentage points above pre-pandemic levels. This would give an underlying rate of between 3.2% and 4.4%.

So not as dramatic as the previous graph indicates.

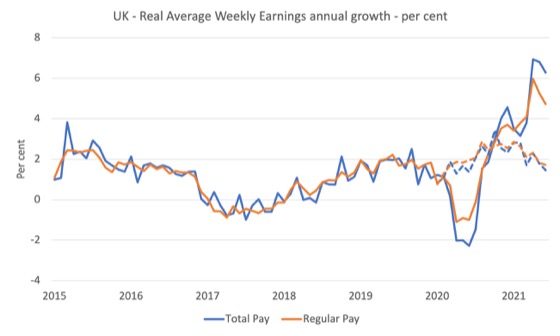

Consider this revised graph, which adds the two dotted lines.

The growth rates in real AWE shown by the dotted lines are calculated by expressing current year AWE in relation to AWE in each corresponding month in 2018 (as the base year), which to some extent overcomes the ‘base’ problem.

The difference is quite stark.

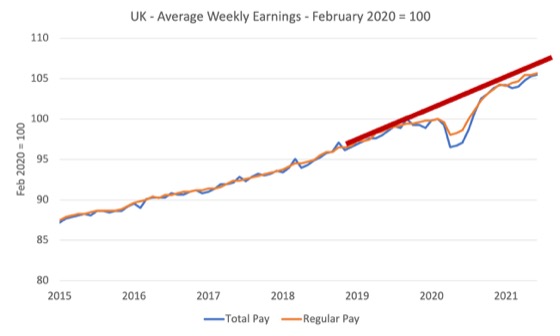

Another way of appreciating what is going on is to compute the series as index numbers with the base-month of 100 being February 2020.

The following graph – which is in nominal terms – provides a good guide to the current wage movement and hardly suggests out of control wage inflation.

The thick red line just guides your eyes away from the period coming out of the pandemic and suggests that wages growth is just returning to the pre-pandemic trend, which wasn’t spectacular by any stretch of the imagination.

But the even more important point is not to try to argue that low wages growth is a good thing or a return to pre-pandemic wages growth, which was hardly flash, is a good thing.

Rather, we should celebrate the ‘market’ working to improve the lot of workers in Britain as the ‘artificial’ excess supply of labour brought on by the unlimited access to low wage labour from the poorer countries in the EU is reduced.

Go back to the first graph and you will see that real wages growth was negative for years after the GFC.

Real AWE fell in June 2008 and then fell continuously until September 2014.

The real wage gains made then turned out to be temporary and real wages started falling again in early 2017.

If we index Regular AWE and the CPI to 100 in April 2008 then it wasn’t until January 2020 that the two indexes coincided again, with the CPI being above the AWE throughout the period.

That is a shocking result for workers, given that during this period, productivity growth was ongoing (albeit weak) – meaning profits were taking an increased proportion of the national income generated.

Overall, the current real gains do not make up for the real losses in the post GFC period.

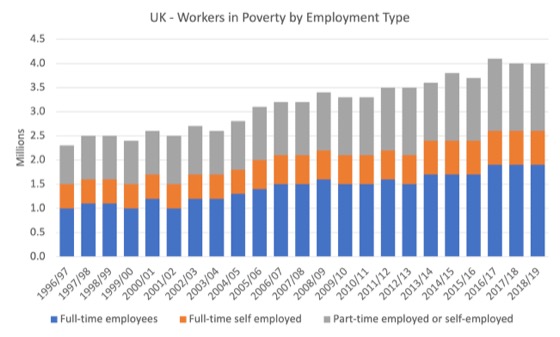

The analysis presented by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation – Workers in poverty – reinforces the conjecture that the British labour market has been failing the workers.

The JRF conclude that:

The number of workers in poverty has increased in recent years. Just under half of workers in poverty are full-time employees, just over 30 per cent are part-time employees and around 20 per cent are self-employed.

The following graph is derived from JRF data and shows the number of workers in different categories who are considerd to be poor.

In modern Britain, poverty has moved into blight those who have jobs as well as those deprived of work as a result of flawed macroeconomic policy settings.

So if wages grow faster than in the past, what’s the problem with that?

UV curve behaviour

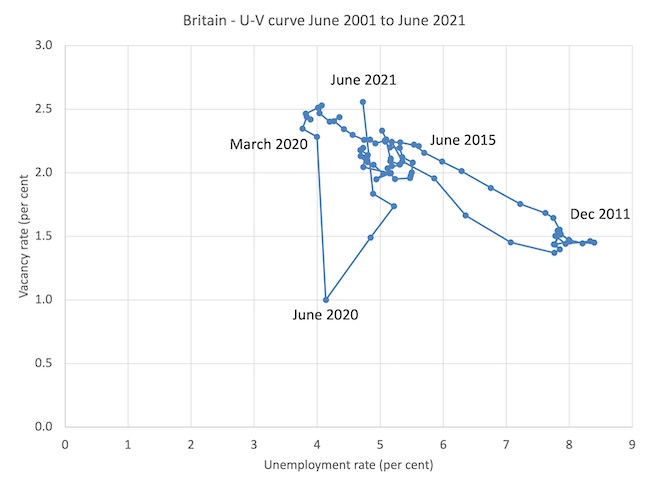

The UV (or Beveridge) curve shows the unemployment-vacancy (UV) relationship plots the unemployment rate on the horizontal axis and the vacancy rate on the vertical axis and is used by economists to differentiate between cyclical and structural shifts in the labour market.

Refer to the blog post – Latest Australian vacancy data – its all down to deficient demand (July 2, 2013) – for a conceptual discussion about how to interpret this framework in terms of movements along curves and shifts in relationships.

Mainstream economists interpret movements along the curve as being cyclical events and shifts in the curve as structural events.

So, in that framework, a movement ‘down along the curve’ to the south-east suggests a decline in the number of jobs available due to an aggregate demand failure, while a movement ‘up along the curve’ indicates improved aggregate demand and lower unemployment.

If unemployment rises in an economy where there are movements along the UV curve it is referred to as “Keynesian” or “cyclical” unemployment – that is, arising from a deficiency in aggregate demand.

The mainstream economics literature claims that ‘shifts in the curve’ – (out/in) – indicate non-cyclical (structural) factors (more efficient/less efficient) are causing the rising (falling) unemployment.

Allegedly, the UV curve shifts out because the labour market was becoming less efficient in matching labour supply and labour demand and vice versa for shifts inwards.

The factors that allegedly ’cause’ increasing inefficiency are the usual neo-liberal targets – the provision of income assistance to the unemployed (dole); other welfare payments, trade unions, minimum wages, changing preferences of the workers (poor attitudes to work, laziness, preference for leisure, etc).

Using this logic in the 1970s, when the shifts were first noticed, mainstream economists argued that the Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment (NAIRU) had risen and that ‘Keynesian’ attempts at reducing unemployment through the use of expansionary fiscal policy would only cause inflation.

They argued that structural policies were needed, which marked the beginning of the neoliberal activation program and the attacks on trade unions etc.

Micro policies like cutting unemployment benefits and/or making it harder to get and remain on benefits became the norm.

The pernicious work test mentality entered the fray.

Industrial relations legislation in many nations made it hard for trade unions to prosecute successful wage claims and minimum wage adjustments stalled or were weak.

The problem was that the evidence used to justify all this was wrongly interpreted.

The shifts in the U-V curve had nothing to do with microeconomic or structural factors.

In most countries, shifts in the UV curve occur during major demand-side recessions – that is, they are driven by cyclical downturns (macroeconomic events) rather than any autonomous supply-side shifts.

Once the economy resumes growth the unemployment rate fall more or less in line with the new vacancy rate and the economy moves back up towards the north-west of the graph.

Here is the British UV curve from the June-quarter 2001 to the June-quarter 2021. I have marked some key date markers to aid your understanding.

It is clear that the British labour market moved down along the lower loop from the centre cluster as the GFC ensued and the Cameron government imposed misguided austerity policies.

As the delayed recovery took hold, the response was expected – vacancy rates rose and the unemployment rate fell in lockstep.

Then the pandemic hit and between the March-quarter 2020 and the June-quarter 2020, vacancies collapsed (falling from 785 thousand or 2.2 per cent to 340 thousand or 1 per cent), while the unemployment rate was largely protected by the policy intervention.

Over the next 12 months, vacancies have risen sharply without the commensurate decline in unemployment. I expect the latter will come soon as firms realise they will have to train local workers if they are to realise their own expansion plans.

Conclusion

Clearly, some firms will be finding it difficult to immediately fill their vacancies and training takes time.

But in the true full employment period, when vacancies tended to outrun unemployment, firms developed a forward-looking mentality to ensure their training programs were concident with their expected labour needs.

Years of unemployment and access to low-paid foreign labour has altered that sense of preparedness.

Brexit will force an adjustment on firms that will serve to benefit the low-paid workers I suspect.

It might make home help a bit more expensive, however, for bankers and other high-paid professional workers in London.

And it is that cohort that tend to scream about the negative consequences of Brexit.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“there were more than 1.6 million who were unemployed.”

Not to mention another 1.7 million “Inactive – wants a job” (sequence LFM2).

Although that sequence is at the lowest it has ever been in the 28 years it has existed.

Just occasionally Larry Elliott in The Guardian braves the mainstream EU loving instinct of his employer and howling Guardianistas – https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/aug/29/so-whats-so-wrong-with-labour-shortages-driving-up-low-wages ‘The evidence is that where workers from overseas complement home-grown workers, they boost earnings. This tends to benefit those at the top end of the income scale. It is a different story at the other end of the labour market ….it is perhaps unsurprising that Brexit divided the nation in the way it did’. Equally unsurprising which way the Parliamentary Labour Party steered; into uselessness.

I’m glad it looks like British worker’s pay may be increasing. Here in the US we are beset by economists telling us that any wage increases are overcome by rising prices as we were hopefully emerging from this pandemic. Which unfortunately does not seem to be happening very well for us.

It would seem that the premise of this analysis, accurate though it undoubtedly is, is that the pandemic is in its final stages, the other “good news” being that Britain will apparently return to business as usual with somewhat higher wages than pre-Covid/pre-Brexit. What happens if the pandemic is not waning, however, in fact is just getting up a new head of steam, as indicated by a number of eminent epidemiologists? I wish that Bill would lay out a scenario for THAT situation, in which Covid mutations and surges intermittently freeze not only local economies but the entire global neoliberal world order. Is anyone aware of any MMT economist who has analyzed how such a chronic Covid future, which we possibly face, might play out?

The capitalist system reached its limits, as exploitation of human beings and resources can no longer be in lockstep with continuous economic growth (meaning continuous profits growth).

It doesn’t work anymore, not even in the UK.

They need ever lower wages and they are searching for workers (that is, workers willing to accept the conditions they have to offer) in ever greatest distances.

In Portugal, the agrobusiness is getting workers from countries like Nepal, on the other side of the world.

But that doesn’t mean that there are pressures on the labor market to rise wages and so, on prices of goods and services.

Rising prices are coming from elsewhere.

They are coming from fossil fuel rising prices, that drives everything else (“green” politics see petrol as dirty energy and look the other way, as companies try to profit big with the recovery).

They are coming from interrupted supply chains.

Long supply chains grew with globalization and were severed with the pandemic.

So, cars manufaturers in europe are interrupting production for shortage of semiconductors, which come entirely from China.

The same with everything else.

I think Bill is over simplifying by claiming that the current labour shortage and wage pressure has been caused by Brexit.

It’s a combination of factors, and you also need to include the effect of the pandemic as well as UK’s more restrictive immigration system, which is a matter of policy, not Brexit.

Vehicle haulage is one area where there is around a 100,000 vacancies, which is impacting on deliveries. Its been caused in part by the inability of the haulage industry to train new drivers due to the pandemic restrictions. Attracting workers for a relatively low paid high responsibility job is also proving problematic, and the UK government is refusing to make visa exemptions to source EU drivers to plug the shortfall. Supply chain disruption will last at least 6 months.

Another area is social care, which again has around 100, 000 vacancies. It’s a low paid job, averaging £8.50 per hour and often has poor terms and conditions. It’s also a highly demanding job and it is not unusual for recruitment drives by care homes to turn up zero applications. The problem is that it is not just about increasing pay, as many homes are running on very tight margins, and would become unviable. It requires significant increases in funding, which is unlikely to appear. It’s another sector affected by the UK’s immigration policies. And the “no jab, no job” policy is like to lead to around another 40,000 vacancies.

Another area is fruit picking. It’s not just that there is a lack of people willing to do this kind of work, it’s highly demanding and skilled work. The average person simply can not pick fast enough to justify their salary. I don’t know how serious it is as a problem, but I was reading reports that fruit crops are spoiling because of a lack of labour.

Mark, there is always this thing that seems to puzzle so many people at times. A company is having problems “attracting workers for a relatively low paid high responsibility job”. Well maybe that job just sucks and if it needs to be done then the people who you need to do it need better compensation. It’s like all these people who say the market will always provide the best outcomes suddenly have some kind of stroke when it comes to the cost of labor for what they deem low-status work.

Saying your average worker just can’t pick fruit fast enough to justify their salary? I don’t know how someone could arrive at that conclusion. If that was the case the fruit won’t be picked. It won’t be delivered to stores. And most of us won’t be able to eat it. And those who really want to will probably have to pay a higher price for it- which will ‘justify’ the fruit picker’s salary. That is how it is supposed to work in economic theory.

Hi Jerry,

The care sector has always had a recruitment problem. I walked into a well paid care job in the late 80’s with zero experience, because I was the only applicant. The UK care sector employs 1.5 million of which around 250,000 are migrant workers. It’s long been sustained by immigrant workers.

The bit about fruit and veg picking was explained to me by a farmer, as to why he didn’t as a rule employ british people. He said he had tried but they weren’t generally fast enough. According to him it’s apparently all too possible to pick less fruit than you are paid. He said he preferred east European workers because they were already experienced and importantly very accurate and fast. Farming is run on very tight margins, it’s a young person’s profession, the average age of a farm worker is around 35 compared to 45 for office workers. It’s also poorly paid and has significant occupational hazards such as pesticide exposure.

It’s one of those low paid supposedly low skilled jobs which only a narrow group of people can perform well, very much like care work.

Mark,

Bananas down here in Western Australia are about $3/kilo. The northern part of WA has many plantations, as does the northern part of Queensland. A few years ago, there was a disaster in Queensland that pretty much wiped out their banana crop. Prices rose to over $15/kilo. The growers in WA made millions in profit. If they had to pay two local workers to have the same output as a trained fruit picker? They still would have made millions in profit.

Immigrant workers aren’t born fruit-picking machines – they have experience and on-the-job training (and, coincidentally, a lack of knowledge about local labour laws). Of course a local person given their first fruit-picking job with no prior training is gonna be slow. But they’ll get faster, if the farmer sees them as an investment instead of a sunk cost.

It is about time employers were forced to offer better training and wages to workers in the toughest jobs. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a good economy as Mosler calls it. Maybe finally I will?

Hi Matt B,

What does a crop failure have to do with a labour shortage? For sure if your crop is fetching $15/kilo, then you can be more relaxed about who you hire. On the second point, it’s not about learning on the job, it’s about workers who have sufficient stamina, accuracy and speed. Care work, haulage drivers, and farm workers are not jobs anyone can do or indeed want to do. Farm work in particular are difficult jobs to fill locally because they are seasonal and most people generally need year round work. Australia is similar to the UK in that 50% of it’s short term contracts are filled by migrant workers.

In the UK fruit picking wages have gone up by 60% to around £20 per hour. It’s being caused by an acute labour shortage, which is not being filled by local workers. Since June, Farmers through the NFU have been reporting crops being wasted, and the latest I read is that around 70,000 pigs are at risk of being destroyed because not only is there a lack of haulage drivers, there is a lack of abbatoir workers. This is yet another industry where 60% are EU nationals – butchery is another low paid but high skill job, which British people are very averse to doing, regardless of pay.

The point is that Bill claims that it is Brexit which has led to higher wages for jobs, but I think he is over-simplifying it. It looks to me more like an acute labour shortage driven by 3 things, Brexit, the pandemic, and the UK’s more restrictive visa system. On the last 2, the Labour force survey has an estimated drop of around 800,000 for non-UK workers during the pandemic, and the NFU and the haulage association are reporting that the UK visa exemptions are not enough to fill the demand – the UK are allowing 30,000 temporary visas for farm work, and zero for haulage.

Dear Mark Redwood (at 2021/08/31 at 5:49 pm)

You note:

No-one said it was all down to Brexit. Given we have a once-in-a-hundred-year pandemic on our hands, only a fool would ignore that.

There is strong evidence that workers are hesitant to offer their services in exposed settings. Clearly.

The point is that Brexit will have labour supply effects in low-wage sectors which will benefit local workers. That is undeniable. There are other factors that will work both ways.

The other point was that it is rather amusing to hear/read the continual whining from middle-class Remainers who tout ‘progressive’ credentials about Brexit as if the sky was falling in. They seem to ignore these positive impacts on the low-wage workers who before it became harder for employers to draw on large pools of low-wage foreign workers had to compete with that pool.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the reply. I have been back through your piece, three times to make sure I understand it as best I can. From the information and arguments presented I think that a more accurate headline would be, “Pandemic is delivering better pay for British workers (on average)”

For the AWE graph the sudden large dip and subsequent recovery are attributed to the pandemic. How much of the effect was due to Brexit? And how would you tell in such a large swing? The baseline correction (dotted line) shows a rate of growth more less the same as 2019, which is when the UK was still in the transition stage. The nomimal graph shows a rate of increase on par with the increase prior to the pandemic and prior to brexit. I am really not seeing much of an effect, and I would also question whether it is possible to divine anything significant about the impact of Brexit on wages when it coincides with such a large impact effect like the pandemic?

Also the UV data shows a dramatic shift in the relationship between vacancies and unemployment, and again highlights how unusual the pandemic has been on economic activity. Is there a Brexit effect in this graph? ( I re-read the article, and I understood it to be a point about that the UV graph mostly shows what happens during recessions/recoveries).

On a side note, Brexit is often mentioned as being a factor. The problem I have with this shorthand is that Brexit is actually a political agreement between the UK and the EU. It’s effects will be determined by the shape those agreements have taken. It strikes me it used so casually, and without explanation, that it has become largely meaningless.

What is it about Brexit which will reduce the availability of labour to the UK? Because surely EU citizens are entitled to claim settled status? A large number have failed to do so in time and a number will be ineligible. We have a much more restrictive immigration visa system which can be temporarily waived if deemed necessary by a minister. These are political decisions, not necessarily a consequence of Brexit. Also what impact are social factors which are connected to Brexit having on migration? For instance about half of EU citizens in the UK report feeling discriminated against, which rises to 60% for Polish nationals, and hate crime spiked following the referendum, and has remained high. It’s around double the rate of 5 years ago.

And yet we in the U.K. still had fruit picked, and lorries driven before EU NMS immigration. How ever did we manage?

It’s delicious seeing farmers and logistics company owners squirm.

The comparison between the eager, Duracell Bunny Polish mangelworzel picker, and the lazy local Brit is specious; it’s comparing an HGVs to radishes.

Your NMS migrant worker is young, bright, physically and mentally healthy, free of caring responsibilities, motivated and adventurous – which is why he or she has left Plomsk and has travelled west to seek their fame and fortune. Comparable more to those Brits who head off to the US, Dubai, or Oz, to start businesses or chase higher pay in professional jobs.

Your average spotty Norfolk or Lincolnshire local is not the same creature, or he or she would have upped sticks and headed to uni or to London, at the first opportunity, to make something of themselves. They are likely instead to be less motivated, less educated or adventurous, and with narrower horizons, perhaps in less than perfect physical or mental health, and possibly with caring responsibilities. They absolutely have their identical counterparts right across the New EU Member States – but we never see them over here in the U.K., for obvious reasons.

Yet these pasty locals managed, historically, to get by perfectly well pre-NMS immigration, picking produce and doing general agricultural labour. As did the farmers, using their labour.

Greedy and exploitative U.K. farmers and employers have been onto a very good thing for the past 20 years or so, scooping up the creme de la creme of motivated, eager, and adventurous foreign workers – at least until such a time as these workers realised they were on a complete hiding to nothing and had no future in the U.K. as caravan-dwelling crop pickers, eventually returning home, perhaps with a little bit of hard-earned cash if they’re lucky, only to be replaced by their just as eager, but sadly naive, younger brothers and sisters.

But enough is enough. These bleating and unscrupulous farmers and employers have been spoilt for too long, and need to up their game to create decent working conditions, proper training, and fair pay in order to once again attract local workers for proper rewards.

That should of course be : “comparing HGVs to radishes”!

Mark Redwood,

What does a crop failure have to do with a labour shortage? In either case there is product going to waste. QED. Decreased supply for any given demand leads to inflation of prices.

You know how workers obtain sufficient stamina, accuracy and speed? Experience and training. Sure, it’s not a job for everyone. No job is for everyone. Some people would hate being office workers, some would people hate manual labour, some people would hate septic tank cleaning, some people would hate driving people around all day. That’s not really a refutation of my point.

Those jobs are difficult to fill locally because farmers , for many years, decimated the local workforce by employing cheap immigrant labour through dodgy labour hire services. And now the bill has fallen due. There’s no inherent inability for seasonal work locally – we still have millions employed as temporary contractors, and there is no inherent difference between, say, laying bricks for a month and picking fruit for month.

Do you think that 20 quid an hour is an unreasonable wage to demand for a farm worker? I certainly don’t. I get about 18GPD sitting on my arse in an air conditioned office doing basic data entry, and I’m far from overpaid. I still get more than the average fruit picker here in Australia, so I’m never surprised about farm labour shortages.

I’m going to point out that if Aust. or the UK had a functioning Job Guarantee Program,

it would be perfectly possible for the Gov. to rent them out to farmers at a loss.

It would even be possible for the workers to work in pairs with one holding a sun shade (then trade places, etc.) so they don’t need to be working in the sun or constantly hard and fast with no time to rest.

This would let the workers have a ‘better’ job (not in the sun) for more money, and for the farmers to be able to make a profit; without having to raise to price of what they produce. Not raising prices is important, if the nation can import food to compete with locally grown food.

.

Hi Matt B

I don’t know what the situtation is like in Australia, however on these specific points in the UK

“You know how workers obtain sufficient stamina, accuracy and speed? Experience and training. Sure, it’s not a job for everyone. No job is for everyone.”

This is a quote from Hardman, director of Hops Labour in 2017,

“The DWP Welfare to Work scheme was an unmitigated disaster. We had about 100 people, and after 12 weeks we had one left. The majority of them walked off the job within two days.”

This is a commonly reported problem, and was highlighted by Migration Advisory Committee report in 2013.

The other two factors which affect recruitment, are that usually seasonal work requires you to lodge at the farm where you are working, relatively few people are willing or indeed able to do that. Also rural areas typically have low unemployment, most unemployment is in urban areas, which are typically a long distance from farms.

Seasonal farm work has always been done by migrant workers. in the 19th Century it was the Irish, in the 50’s and 60’s in the villages where my mother grew up it was gypsies. SAWS, Seasonal Agriculture Workers Scheme ran from 1954 to 2013. However the real drive to increase migrant workers in the sector was caused by the increasing centralisation and dominance of the supermarket chains which have squeezed prices. Supermarkets are noted for their sharp practices in negotiating contracts with farmers.

Thus farmers now rely on a relatively small group of specialised migrant workers, who as I said have high stamina, are very accurate whilst also being very fast. Around 90% of seasonal farm work in the UK is filled by migrant workers.

“Do you think that 20 quid an hour is an unreasonable wage to demand for a farm worker?”

No, I don’t think it’s unreasonable, but even at £20 per hour, there is still a labour shortage. I believe though this is actually a piece rate. I would not even get close to that rate of pay, I’d be unlikely to be able to work fast enough to justify being paid even a minimum wage. (and yes according to a farming acquantaince I know this is actually a thing)

Farmers are saying that the current situation is not sustainable. One factor is the increased wage rates, but the main factor is the uncertainty, and nobody in the sector knows where the labour required is going to come from if it is not filled by migrant workers.

And I guess you can shout all you like about “[that] famers for many years, decimated the local workforce by employing cheap immigrant labour through dodgy labour hire services” but firstly it’s not true of all farmers, it’s only true of a few farmers, and secondly it does nothing to resolve the current problem farmers are experiencing. The long term solution is likely to be roboticisation of seasonal farm work.

“Farmers are saying that the current situation is not sustainable. One factor is the increased wage rates, but the main factor is the uncertainty, and nobody in the sector knows where the labour required is going to come from if it is not filled by migrant workers. ”

So how, exactly, did UK farmers manage in the years *before* immigration from EU New Member States in the early 2000s?

We didn’t starve, and the only period of significantly high inflation we suffered was due to the 1970s oil price hike.

“However the real drive to increase migrant workers in the sector was caused by the increasing centralisation and dominance of the supermarket chains which have squeezed prices. Supermarkets are noted for their sharp practices in negotiating contracts with farmers.”

I’d say that’s your problem, right there.

Dutch unions negotiated higher rates for HGV drivers, and once those were established, the supermarkets couldn’t haggle delivery costs down below that level. Perhaps the same thing needs to happen with agricultural wages. Farm workers need to be unionised and demand higher pay – no better time than now, while their bosses are desperate.

In time, farmers will increase automation, as they absolutely should.

Hi MrShigemitsu

“So how, exactly, did UK farmers manage in the years *before* immigration from EU New Member States in the early 2000s?”

Immigration has always been a part of seasonal farm work. From 1954 until 2013, the UK had the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Scheme. The UK also had the gangmaster system, which was less regulated but had problems with worker exploitation. The nostalgic picture you painted of norfolk and lincolnshire lads never really existed. Seasonal workers when they were from the UK would be bussed in from places like Yorkshire and the Midlands.

The Dutch agricultural system has similar problems around exploitation of migrant workers as the UK farming system. It’s time I think to take the rosy tinted spectacles off…

“The Dutch Labour Inspectorate (Inspectie Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid, ISZW) considers agriculture in the world’s second largest agricultural exporter one of the top risk sectors for unfair work. In Dutch agriculture, “a flexible contract with a low wage and little certainty is the rule rather than the exception and employment agencies, contracting and payrolling are also widely used” as a result of efforts by growers “to keep prices low by reducing labour costs with all kinds of mechanisms to below the legally required minimum or collective wage.” Consequently, many migrant farmworkers in this rich country experience working poverty. Migrant workers from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) form the bulk of the agricultural labour force. About a fifth of them work at or below the minimum wage, earning an average of ten euros an hour, half the wage of other European workers employed in the Netherlands.”

September 2020

https://www.arc2020.eu/the-netherlands-are-agri-food-workers-only-exploited-in-southern-europe/

All the Polish people I know in UK (and I know quite a few) are very very hard working. And that’s what all UK employers say about them.

It’s a wonder that Poland isn’t a very very prosperous country, isn’t it?

I grew up in Somerset in the UK where there was plenty of seasonal agricultural work, including fruit picking. Many of my friends and I made money over the summer holidays while at university in the late 90s doing such jobs. There was no sign of any labour from outside the local area (whether from elsewhere in the UK or from overseas) and it was definitely unskilled work.

Sure, people would get better with time and the farm manager preferred to hire the same people each year but there was absolutely no expectation that anyone had prior experience. Since it was acknowledged that it was hard work, we were paid above the minimum wage at the time and my friends who wanted easy jobs instead got summer work in offices and factories where they were paid less.

The last year I worked there was 1999, however, I was informed by a relative who worked on the farm that in subsequent years labour was provided by seasonal eastern European immigrant labour living in temporary accommodation who were paid less than us students but who were also less productive. I do not know what happened after those years but the farm did not go out of business and the farm owner is still a multi-millionaire (apparently).

Great comment, Xochil. I’ll share on FB and Twitter anon – ah, but you are anon.