I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

I vote, I am unemployed and I live in your electorate

Today, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time. Today he is writing about the uneven impact of the government’s withdrawal of its COVID economic support packages aka JobSeeker and JobKeeper. Keeping with some of his earlier blog posts here, Scott takes a spatial angle and considers what might be some of the implications when exposure to the impacts of the government’s changes are concentrated at the level of federal government electorates. Anyway, while I am tied up today it is over to Scott …

I vote, I am unemployed and I live in your electorate

There is no doubt that the Australian government’s COVID-19 economic support program has helped a number of people and companies during the economic slowdown associated with the health crisis.

Although it has fallen short in a number of areas, in for example the arts and in universities, it has stopped a much bigger economic calamity occurring than would have been the case if it wasn’t undertaken and has, provided the unemployed with higher levels of support than they have had in the past.

Given this, there certainly was no surprise that the news that the government was going back to its old ways of hand wringing about not being able to afford to support some of our most disadvantaged individuals – the unemployed – and those who might become unemployed has been an area of increasing concern across many in the community.

In a 9News Report yesterday (March 29, 2021) – “>Treasurer defends end of JobKeeper – the Treasurer commented on his decision to end of the Federal wage subsidy program, Jobkeeper:

JobKeeper had to end to revitalise the economy … [because] … It would prevent workers moving across the economy to more productive roles.

Last year, the Australian newspaper story (July 26, 2020) – Treasurer Josh Frydenberg defends JobKeeper payment cuts – quoted the Treasurer as saying:

Australia cannot afford to continue spending $11 billion a month on JobKeeper …

Similar comments have been made about the necessity to wind back the amount of income support provided to the unemployed.

The usual old arguments about responsible fiscal management or excessive payments being a disincentive to find work.

Just another bunch of comments showing how out of touch the Treasurer and others are with how things work in the real world. How nice it must be to reside in the Canberra bubble.

The concerns within the community about the demise of JobKeeper have been widely reported.

Headlines have warned:

1. “Up to 250,000 jobs could be lost as JobKeeper ends” – Source (March 5, 2021).

2. “At least 2.6 million people face poverty when COVID payments end and rental stress soars” – Source (March 24, 2021).

3. “Covid supplement end will mean being pushed further into poverty, Australia’s jobless warn” – Source (March 9, 2021).

Only time will tell as to how bad the reversal in employment growth will be as a result of the abandonment of the wage subsidy.

But for individuals who have been reliant on income support through the JobSeeker program or those who have managed to keep their jobs because of the JobKeeper payment, there is clearly real trepidation.

But it is not just the individuals directly impacted that are cause for concern.

Some communities will face greater exposure to the withdrawal of government support measures which will have much wider implications.

I talked about this in my blog post – Using a regional lens reveals the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash (February 11, 2021) – where we saw that:

When we use a regional lens to consider economic outcomes we are faced with another picture of social and economic winners and losers …

The gist of the blog post was that further problems begin to emerge once we start thinking about how disadvantage becomes concentrated in communities.

These things often appear lost in government thinking, especially when they are more focused only on the big picture national or state level economic outcomes.

And so too does the potential political fall-out from significant concentrations of disadvantage including unemployment.

There is plenty of evidence about what can happen when there are enough ticked-off voters.

Rex Davis and Robert Stimson analysed the rise of the One Nation party in the Queensland state election in 1998 in their article – Disillusionment and disenchantment at the fringe: explaining the geography of the One Nation Party vote at the Queensland election (May 4, 2017).

They saw the rise as being, in part, a result of a significant number of disgruntled voters wanting to send the traditional parties a message.

In a similar way, many believe that the 2016 election win by Donald Trump in the US was partly a result of his ability to reach out to voters disenchanted with the establishment and similarly, the support that the vote to leave the EU (Brexit) received in the UK signalled a similar discontent.

As the LA Times Editorial (June 24, 2016) put it – Brexit’s lesson: Do not underestimate angry voters.

This point was made in a recent report from the Australian Council of Social Services (March 15, 2021) – New data shows people affected by JobSeeker cuts could decide results in next Federal election.

They pointed to the potential political impact of concentrations of unemployed people in marginal electorates and I have made the same point in some recent analysis of the data – Covid-19 Economic Support and Withdrawal Exposure.

From my analysis, that looks at the impact of the stopping of JobKeeper and the reduction in the level of support for JobSeeker, we learn that there are serious inequalities in the potential exposure to the withdrawal of the government’s COVID economic support package.

The basic argument here is that in electorates that have high proportions of people on job seeker and higher proportions of people getting job keeper, the governments changes leave them exposed to significant economic uncertainty and disadvantage.

From the data we see that putting aside the Northern Territory which only has two electorates, electorates in the states of Queensland and South Australia and to a lesser extent Victoria have significant exposure, relative to other states.

The following Table tells the story.

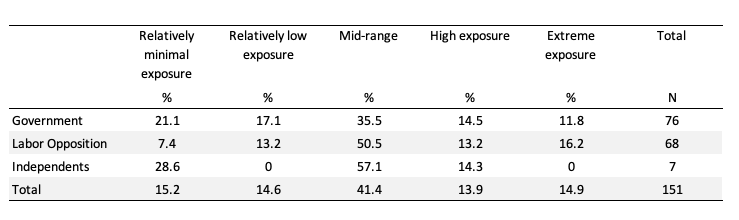

The next Table tells us that seats held by the Australian Labor Party (Federal Opposition) are over represented in those electorates classified as facing extreme exposure, compared to seats held by the conservative Liberal-National Coalition which were well over represented in those electorates with relatively minimal exposure.

Taking a deeper dive into the data, we see that the seats held by the Prime Minister, the Treasurer and the leader of the opposition are all classified as having relatively minimal exposure.

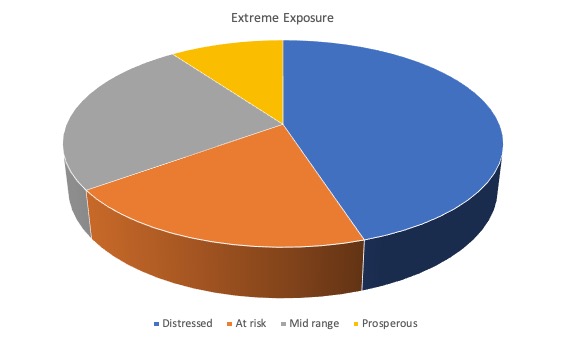

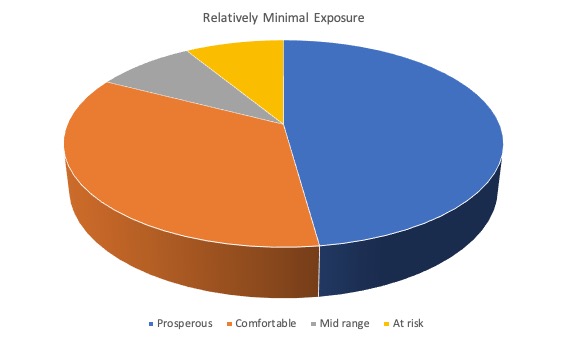

Going further, if we were to overlay this data with data from our research published in the paper – Prosperity and Distress in Australia’s Cities and Regions (May 2019) – we see that the large majority of electorates counted as being highly exposed to the withdrawal of COVID support, were among those that our early research identified as being among some of the country’s most distressed or at-risk localities, while those with relatively minimal exposure were among the country’s most prosperous localities.

So once again, as I pointed out in my blog post – Using a regional lens reveals the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash (February 11, 2021) – it is those places that were already disadvantaged prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 that will be hit hard and when recovery does take place the gulf between the advantaged and disadvantaged will remain and might have even grown.

As I have said in the past, ‘we are all in this together, except when we are not’.

One would imagine that if the politicians were doing their jobs, representing the people and communities that voted for them, then those MPs representing the electorates that are most exposed to the withdrawal of the economic support (or in fact all MPs) should be jumping up and down and demanding that their leaders do something.

After all, they are working with our best interests at heart. Right?

Looking at the carry on that takes place in the name of political debate and the development of informed policy, it seems unlikely that many MPs have their constituents are front of mind.

Instead, they just seem to fall in behind the party machine and do a lot of nodding while the leaders talk about the need for fiscal responsibility, the strength of the economy or some such thing.

We have all seen those stickers ‘I shoot and I vote’ and there is plenty of evidence of the political clout that organisations such as the Australian shooters union or the National Rifle Association in the US has.

Imagine if we started to see ‘I am unemployed and I vote’ stickers popping up? Maybe the message might start getting through?

Conclusion

As always … the fight continues!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Please could you match up the segment colours on your pie charts so that the eye is not deceived by the same blue that shows distressed in the first showing prosperous in the second.

“As I have said in the past, ‘we are all in this together, except when we are not’.” The question is what this “this” is that we’re supposedly together in. I see two quite different versions of “this.” One is that we’re together, supposedly, in weathering the Covid storm so that things can go back to the neoliberal normal. The other is that we’re together, supposedly, in a great socioeconomic reset of our prior way of life, recognized even by many in the mainstream (i.e., in recent Davos rhetoric) as inhumane and ecocidal. While both versions of “this” involve getting us through the pandemic, the divergence couldn’t be sharper when it comes to how we are to come out the other side of it, whether Covid is merely something to put behind us ASAP in order to return to business as usual, or whether Covid is an unprecedented opportunity, almost a gift given us, to go somewhere new, to move, supposedly together, toward a better, more beautiful world. We gloss over this sharp distinction at our peril.

Great article. I think the breakdown of the impact is significant and is an important lesson. Getting angry and voting Trump et al is not a solution either, as we saw 2016-2020.

If the jobs are more productive, then wouldn’t workers move to those jobs without government having to retract the jobkeeper?

Given the word choice and logic, one is tempted to think that the treasurer is trying to force people into higher productivity but same wage (therefore, more surplus value) jobs.

I think people don’t realize that the best way for someone to come off income support is for them to have employment that pays a decent wage. There is no incentive for capital do that. In fact, the incentive is for it to do the opposite.

My family was not doing well even before COVID (USA). For our Black population, this system is absolutely brutal (but not news, sadly). Can’t tell you how many mentally ill & homeless people of color we have in Los Angeles.

Fact is that we are still living in a class society. The rich’s wealth is built on poor people’s poverty. Their happiness is built on poor people’s misery.

Finally, I disagree with the idea that politicians are there to serve poor people because there is no evidence for it. Its high time we recognize that. They are there to rule and deceive. If “they” make all the decisions, it doesn’t matter even if COVID has made “us” learn anything about capacity of the government to spend and so on…

We need to organize a working class movement (trade union etc) armed with the best theories.

Yes, the fight continues!