Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

The long-term unemployed are not an inflation constraint in a recovery

I gave some advice to a politician last week who had read some MMT literature that he said indicated that using the Job Guarantee reduces inflationary pressures in a recovery relative to a situation where a nation had an unemployment buffer stock. I was surprised by the question because the assertions didn’t appear congruent with the facts. It appeared to be rehearsing and endorsing the standard neoliberal supply-side agenda that defined the so-called ‘activation’ approach to unemployment, which militated against job creation programs in favour of training initiatives – the full employability rather than the full employment mindset. The fact is that long-term unemployment always lags behind the overall unemployment movements given it takes time for people to work their way through the duration categories until they get to 52 weeks, after which the national statistician terms a person long-term unemployed. The longer the recession the higher average duration of unemployment becomes and the larger the pool of long-term unemployed as people start to flow into that category. However, the way we think about solutions has been influenced by the myths about the way long-term unemployment behaves, which we summarise as the – ‘irreversibility hypothesis’. This idea has influenced governments to rely on training approaches rather than job creation as solutions to unemployment. And, it has led to the various pernicious unemployment management policies where the victims of the system’s failure to create enough jobs are considered culpable in their own misfortune and shunted through a series of compliance processes in order to receive income support, which do little to get them work.

The argument the politician presented to me was that:

1. Employers do not know whether a long-term unemployed person has desirable traits and will prefer to employ a short-term unemployed person.

2. So employers choose not to employ the long-term unemployed in a recovery and instead compete among each other for those already employed.

3. The wage chase then causes inflation.

4. So the long-term unemployed represent an inflation constraint until they are subjected to attitudinal training so they work with others, training etc.

5. In other words, stimulating the economy will only induce inflationary pressures if there is a significant pool of long-term unemployed.

6. The solution is to have a Job Guarantee, where the workers are ready for work and reduce the inflationary pressures in an expansion.

All but the last point, could have been written by a supply-side oriented, mainstream economist. The type I have been opposing for all my career.

The problem with this sort of reasoning is that it doesn’t reflect the empirical world.

1. Obviously, if there is an all out bidding war in the private labour market for labour for workers who are already employed then the rising nominal wage pressures may provoke an inflationary spiral.

Whether this does become inflationary depends on what else happens. For example, if productivity growth provides the room to accommodate the nominal pressures and unit labour costs do not accelerate then for given margins there will be no inflation.

2. The empirical evidence is clear – when a recovery occurs, employers bid for labour out of both the long-term and short-term unemployment pools.

The stronger the recovery, the more quickly the long-term get absorbed.

But usually there is not a sequential process where the employers exhaust the short-term pool and then turn to the long-term pool.

And when the labour market tightens, the employer’s job offer is typically a package, which combines some job specific training and a wage offer.

It is generally cheaper for firms to do that rather than try to bid workers away from other firms.

Moreover, firms with market power (meaning they have price setting volition) rarely try to compete on price (up or down).

When sales opportunities increase they defend their market share first and foremost.

They fear that if they push prices up and their immediate competitors do not then they will lose market share which is very costly.

As a result, they will avoid adopt non-price strategies that allow for increased production (and employment) to meet the rising demand for goods and services.

3. A Job Guarantee is not inflationary, in itself, because the government is buying off the bottom of the market – offering a fixed price for a resource that has zero bid in the market.

That is the point.

The government offers an unconditional job offer at a socially-inclusive minimum wage to anyone who wants to work and cannot find it. There is no competitive process from the side of the government.

They just act passively – that is, the Job Guarantee acts as an automatic stabiliser and the pool rises and falls on the tide of non-government spending.

The pool will increase for two reasons:

(a) The government is tightening policy settings to cut into an inflationary spiral in the non-government sector, or

(b) There are no inflationary pressures but the non-government sector cuts spending for any number of reasons – uncertainty, excessive debt, etc

4. Clearly, if there is a Job Guarantee in place, then in the early days of a recovery, when the Job Guarantee pool might be bigger than usual, the wage offers required to bid the workers back into the private labour market may be modest and there are plenty of workers available, so it is unlikely that there would be any inflationary pressures.

It is also true that Job Guarantee workers are more attached to the labour market than the unemployed.

But the hysteretic mechanisms that see firms relax and tighten hiring standards and combine training slots with jobs slots at different points of the economic cycle also mean that the long-term unemployed are absorbed along with the short-term unemployment when economic growth is strong enough coming out of a recession.

I provide some evidence of that below.

In a deep and long recession, the number of long-term duration Job Guarantee workers will be higher than if the recession is short and sharp.

If the recovery is strong enough, then they will get absorbed back into the employed workforce just as they would be if they were long-term unemployed.

5. But once the economy gets close to capacity and the Job Guarantee pool is minimised, then any extra bidding from that pool will be stronger than before and the margin over the Job Guarantee wage that would arise will be larger than before. Again, this might not spark inflation but it is more likely to than before.

6. The point is that the price anchor provided by the Job Guarantee becomes moot when the pool of jobs becomes very small, just as in the case when the unemployment pool is small.

The difference between the two buffer stock mechanisms, however, is that if there are inflationary pressures in the non-government sector, and the government tightens policy settings to suppress them, then under the unemployment buffer stock approach, workers lose their jobs, whereas under a Job Guarantee workers are redistributed from the inflating sector to the fixed price job sector.

While neither system is ideal, the employment buffer approach is vastly superior to using the unemployed as a front line fighting force to discipline distributional struggles between labour and capital.

Definitions

The first issue to clear up is the definition of long-term unemployment. Long-term unemployment tracks the total unemployment rate in a lagged fashion. So as governments abandoned full employment in the in the 1970s and allowed unemployment to rise significantly, they also had to then contend with the politically troubling issue of long-term unemployment.

The solution they took was the purely political – they redefined long-term unemployment. So in the early 1970s, a person was long-term unemployed if they has been unemployed for 13 or more weeks. This was changed in the late 1970s to 26 weeks and from the mid-1980s to 52 weeks. There is on-going pressure change the threshold to 104 weeks and confine it to a small number of so-called intransigents.

The changes were designed to disabuse the citizens of the severity of the problem that occurs when government’s fail to deal with an economic downturn in a timely and sufficient manner.

This has become a common problem during the neoliberal period.

Patterns of unemployment duration

First, what is the pattern of unemployment duration?

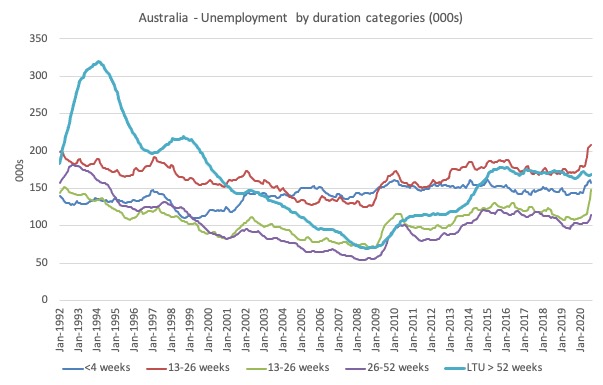

The next graph shows the pattern of unemployment duration in Australia since January 1992.

It shows the evolution of the workers (000s of persons unemployed) across the duration of unemployment categories (in weeks) since February 1992.

The consistent dataset begins in January 1991 and I have calculated 12-month trailing moving averages of raw ABS data to allow you see trends a bit better.

The graph provides interesting information about how the pool of unemployment builds as the cycle turns down. After a long period of growth, long-term unemployment (currently defined as more than 52 weeks of continuous joblessness) is relatively low and workers enter and exit the unemployment pool regularly as jobs are created and destroyed.

The initial spike is because the series starts about a year after the severe 1991 recession and the lack of policy response over the 1990s saw a slow decline in all categories of unemployment. But the longer the recovery was delayed the more workers flowed into the LTU category.

Once the downturn started (February 2008), the short-duration categories obviously take the initial unemployment. So the 4-13 weeks; 13-26 weeks; 26-52 weeks categories all rise sharply in a lagged pattern with the shorter-duration categories lead.

As the recession persists, you start to see the longer-duration categories rising sharply (the dynamics are suppressed somewhat by the moving-average construction of the time series).

The irreversibility agenda

As unemployment started rising in the 1970s and has mostly persisted at high levels ever since, orthodox economists concentrated on the supply side of the labour market, hypothesising that full employment should be redefined to occur at much higher unemployment rates than in the past.

My definition of full employment is less than 2 per cent official unemployment, zero hidden unemployment and zero time-based underemployment.

I base this on the view that the government can always run the economy at sufficient pressure to absorb all the workers who desire a job.

And if we introduce a Job Guarantee, then the problem of involuntary unemployment disappears as does time-based underemployment (because Job Guarantee workers can always choose their own hours).

Skills-based underemployment where a worker may not be able to find a job in their given skill range is more difficult and open to all sorts of definitional issues.

The reminder from American economist Michael Piore (1979: 10) is also worth remembering:

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original)

(Reference: Piore, M.J. (ed.) (1979) Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc.: White Plains.)

The orthodox approach, however, has been to consider long-term unemployment to be a (linear) constraint on a person’s chances of getting a job.

The so-called negative duration effects (scarring etc) are meant to play out through loss of search effectiveness or demand side stigmatisation of the long-term unemployed.

That is, they become lazy and stop trying to find work and employers know that and decline to hire them. Over this period, skill atrophy is also claimed to occur.

All sorts of vile nomenclature was then introduced to make sure that the workers were divided between those who worked and those who didn’t – the latter being bludgers and more.

So it has been common for mainstream economists and policy makers to postulate that there is a formal link between unemployment persistence, on one hand and so-called ‘negative dependence duration’ and long-term unemployment, on the other hand.

Although negative dependence duration (which suggests that the long-term unemployed exhibit a lower re-employment probability than short-term jobless) is frequently asserted as an explanation for persistently high levels of unemployment, no formal link that is credible has ever been established.

However, despite the lack of evidence, the entire logic of the 1994 OECD Jobs Study which marked the beginning of the so-called supply-side agenda defined by active labour market programs was based on this idea.

This was the period when governments abandoned their Post World War 2 commitment to full employment, and, instead, adopted the diminished, supply-side goal of full employability.

The import of that shift was that governments stopped dealing with downturns in non-government spending, especially when the downturn was severe, with direct job creation programs, and, instead, introduced supply-side programs – training, attitudinal coaching, CV preparation and all the rest of it.

Labour market recoveries from downturns in the full employment era were much more rapid because governments used their fiscal capacity to address the spending gaps.

In the neoliberal era, a major downturn which drives unemployment up sharply, results in a slow, drawn out recovery where unemployment takes many years to recover.

This period also coincided with the creation of a new industry. We mostly think of industries as being where production occurs – adding value to our lives.

In the neoliberal period, the Financial sector grew quickly which is largely unproductive (wealth shuffling).

But another, new industry was also created – the unemployment industry.

In Australia, the government privatised the Commonwealth Employment Service and created a sort of quasi-market where all sorts of private companies (including Churches – to their eternal shame) tendered to offer case management services for the unemployed under the guise of preparing them for work.

In addition, the governments (federal and state) started starving the public education system of funds and created a private training system where all sorts of fly-by-night operators emerged, where a steel set of shelves with a single book would be called a ‘library’ and millions of dollars were given to them under the guise of vocational training.

And the job service providers became the front-line attack dogs for government in that they implemented the pernicious welfare-to-work regulations.

The entire system was a depoliticised farce with terrible impacts for the victims – the unemployed seeking income support at a time when the government austerity starved the economy of job creation potential.

All this was justified by the claim that the long-term unemployed were unemployable and unless they were trained up and disciplined to have better work attitudes then they would never be absorbed back into work.

And if governments tried to stimulate an economy where there was significant long-term unemployment then inflation would result – because employers would just compete among the existing employed workforce to expand.

The question as to why anyone was long-term unemployed fell to the back of the public debate.

Does long-term unemployment have strong irreversibility properties?

There is little credence in the irreversibility hypothesis.

Once you examine the dynamics of the data you quickly realise that short-term unemployment rates do not behave much differently to long-term unemployment rates.

The irreversibility hypothesis is unfounded.

Clearly, if the government allows a downturn in non-government spending to descend into recession and refuses to stimulate the economy in any significant manner then long-term unemployment rises just because of the movements of the short-term unemployed through the duration categories.

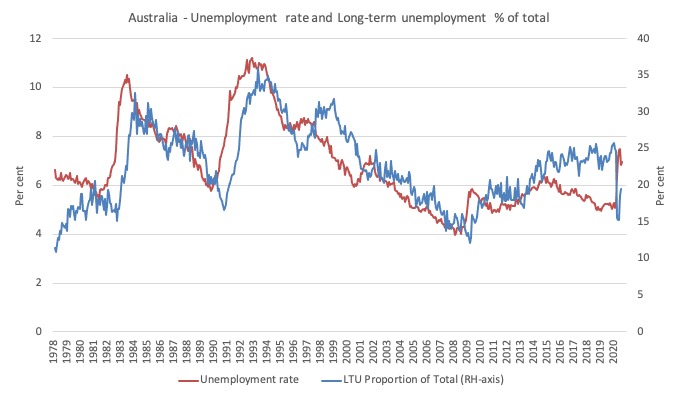

But the data shows that the relationship between long-term unemployment and the unemployment rate is very close as can be seen in the following graph.

We have defined short-term unemployment as the residual between long-term (above 52 weeks) and total unemployment. The dataset used here is seasonally adjusted from February 1978 to August 2020.

As unemployment rises (falls), the proportion of long-term unemployment in total unemployment rises (falls) with a lag.

Several studies have formally examined this relationship.

My earlier work has found that a rising proportion of long-term unemployed is not a separate problem from that of the general rise in unemployment.

This casts doubt on the supply-side policy emphasis that OECD governments have adopted over the last two decades.

So while the mainstream economics profession may claim search effectiveness declines and this contributes to rising unemployment rates, the overwhelming evidence is that both are caused by insufficient demand.

The policy response then is entirely different.

To argue that long-term unemployment is a constraint on growth and therefore needs supply-side programs rather than direct job creation, you would have to find that even during growth periods, long-term unemployment was resistant to decline.

How have the LTUR and STUR behaved over the business cycle? Is there evidence that the LTUR is resistant to growth as is claimed by the irreversibility hypothesis?

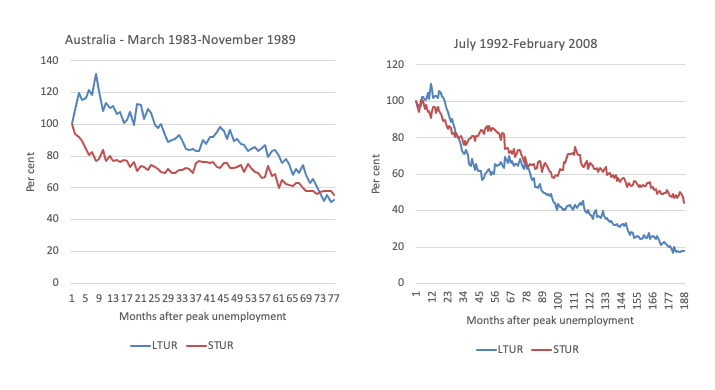

The following graph shows the decline in the LTUR and the STUR from the unemployment rate peaks coinciding with the 1982 and 1991 recessions, respectively.

The peaks were in July 1983 and July 1992. The observations are indexed with the peak observations being 100. The behaviour is charted out until low-point is reached.

The peaks for the short-term unemployment rate precede that of the long-term unemployment, which in turn, lag the related troughs in GDP.

The important finding is that the growth phase provides job opportunities for both pools of unemployment.

There does not appear to be any sequential accessing of the short-term first, followed by the long-term unemployed, as the irreversibility hypothesis would suggest.

Indeed, following the 1991 recession, the long-term unemployment rate fell much more sharply than the short-term rate.

I also have examined the possibility that this could have been due to labour force exit and I largely reject that proposition as an explanation.

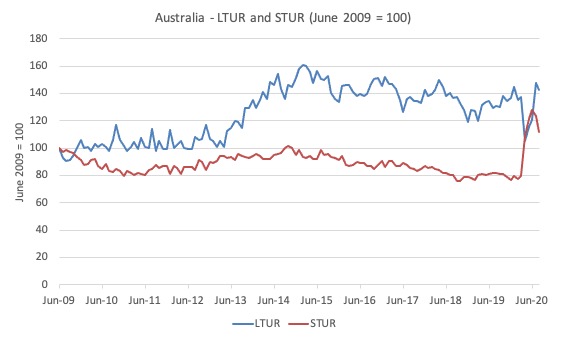

And this graph shows the most recent cycle after the GFC. The unemployment rate rose from 4 per cent in February 2008 (the low-point of the previous cycle) to 5.9 per cent by June 2009.

The initial fiscal stimulus then started to reduce the short-term unemployment rate but was not strong enough to start eating in to the long-term pool.

By 2012, the Federal government was under extreme pressure from the conservatives to start cutting the fiscal support, which they did, and the economy nose-dived and unemployment started to creep up again, which meant that more and more workers at the longer end of the short-term category started to move into the long-term unemployed pool.

And the on-going pursuit of fiscal surpluses has meant it has been very hard for the long-term unemployed to gain work.

This period shows what happens when the economy is slowed due to fiscal drag which reduces duration transitions away from the longer duration categories.

And then the pandemic struck and short-term unemployment has shot up.

Conclusion

The evidence very strongly supports the view that long-term unemployment rises and falls with net job creation. The stronger is employment growth the more quickly long-term unemployment falls.

When recoveries are stalled and slow, the long-term unemployed get trapped in that state.

And in the periods examined, there is no evidence that as the pool of long-term unemployed was declining (simultaneously with the short-run pool) that inflation was accelerating.

It is far better for the government to ensure there is strong spending support when non-government spending declines to prevent the build up of long-term unemployed in the first place.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“..following the 1991 recession, the long-term unemployment rate fell much more sharply than the short-term rate….”

Bill, have you considered the possibility that this could have been due to Hawke/Keating 1989 changes to the casual employment IR regs to eliminate a pre-existing 3 month time limit on casual employment?

Perhaps the enabling of lower paid ‘permanent casuals’ drew mainly from the LTU pool.

Soon after 1989 IR changes, the under-employment rate (which prior to that time ranged 2% to 4% below the unemployment rate) ‘crossed over’ and has continued to exceed the unemployment rate ever since – exceeded UR rate by ~3% pre Covid.

The disgusting statements of the politician are the reason why I came to a conclusion. Whenever I hear someone talk about CHIP, SNAP, Medicaid, or how the wealthy and powerful banks were forced to make loans to people who couldn’t afford them by the do-good liberals, I say if you look within the statements, you reach a truth about the wealthy and the powerful – THEY FEEL WE WOULDN’T HAVE ANY PROBLEMS IF WE DIDN’T HAVE TO TAKE CARE OF THE POOR, WEAK, SICK, OLD. The message is implied; contempt for the weak and vulnerable. The policies they are projecting, and here in the US, I tell them – the republican party isn’t really a Christian Party. It shuts them up.