The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

ECB confirms monetary policy has run its course – Part 2

This is Part 2 of my two-part commentary and analysis of the – Monetary policy decisions – by the ECB (September 12, 2019). In Part 1, I discussed the shifts in the deposit rate and the changes to the Targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). In Part 2, I am focusing on the decision to introduce a two-tiered deposit rate on excess reserves, which is designed to reduce the costs of the penalty arising from the negative deposit rate regime that the ECB has had in place since June 2014. But the most important aspect of the ECB decision was not the monetary policy changes, which will have relatively minor impacts on the real Eurozone economy. The telling part of the whole episode was Mario Draghi’s comments on fiscal dominance. We are entering a new era where the neoliberal obsession with so-called monetary policy reliance is becoming increasingly discredited and exposed by the evidence base. Fiscal dominance is approaching. And the only body of work that has consistently argued for this approach to macroeconomic policy making has been Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) despite what the mainstream economists who are now starting to realise their reputations are in tatters might say.

Negative deposit rates go further negative

In its latest decision – spelt out in the Press Release cited in the Introduction, the ECB also decided to :

(a) Set the interest rate “at the level of the average rate applied in the Eurosystem’s main refinancing operations over the life of the respective TLTRO”.

This rate is currently set at zero.

(b) If a bank lends over a benchmark “the rate … will be lower” and “be as low as the average interest rate on the deposit facility prevailing over the life of the operation”.

This rate is now -0.50 per cent.

Overall, even though this is providing the banks with cheaper credit than before, the fact remains that the rather weak credit growth in the Eurozone is driven by the lack of demand from credit worthy borrowers rather than the supply cost of finance.

With weak growth and the ever-present danger of reversion back into recession, it is little wonder that demand for investment loans remains subdued.

The ECB explained the logic of its negative interest rate in this statement (June 12, 2014) – The ECB`s negative interest rate.

The ECB wants monetary policy to be ‘accommodative’ yet, the banks are motivated to pass the cost of the excess reserve penalties onto their borrowers which works against the intent of the policy.

For the German media, the meaning of the ECB’s monetary gymnastics is clear.

Mario Draghi was asked at his press conference to comment on the claims by:

… the CEO of the Deutsche Bank recently said at a conference that if the ECB is continuing this type of monetary policy it may lead or will lead to a destabilisation or a collapse of the financial system

The popular press in Germany is clearly running a campaign against the ECB.

This graphic appeared in the conservative daily German newspaper Bild-Zeitung and depicts ECB boss Mario Draghi as a blood-(saving)-sucking monster preying on the hard efforts by Germans to save.

The Bild story (September 12, 2019) carried the headline “So Draghila sucks our accounts empty. During his tenure we have lost billions”.

Choice.

The story said that Draghi was costing German savers billions in lost euros and his “monetary madness” was “devastating”.

Immediately following this rather scandalous depiction of Mario Draghi, Bundesbank boss, Jens Weidmann, gave an interview to Bild – Ist unser Geld in Gefahr? (September 13, 2019) – or “Is our money in danger?”.

The link is to the English translation provided by the Deutsche Bundesbank. Their translated version (September 14, 2019) carries the heading “Weidmann: ECB Governing Council has gone too far”. I will return to his assessment a bit later.

But the fact he gave an interview to the Bild-Zeitung soon after they had displayed Mario Draghi in that light tells you a lot about the German mentality in this respect.

Anybody else would avoid dealing with a rag like Bild-Zeitung for displaying Draghi as Dracula. Especially when, as you will see later, the German banks will be the largest beneficiaries of the changes the ECB announced last week.

The Financial Times article (September 14, 2019) – There’s a German word for negative rates – said that there is:

… a widespread perception across Germany that the ECB is penalising savers through its monetary policy … former finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble blamed it for 50 per cent of the rise of the anti-European Alternativ for Deutschland party.

The President of the De Nederlandsche Bank, Klaus Knot also joined the chorus.

In an official DNB Press Release (September 13, 2019) – Klaas Knot comments on ECB policy measures – criticised the ECB’s policy decisions, claiming:

This broad package of measures, in particular restarting the APP, is disproportionate to the present economic conditions, and there are sound reasons to doubt its effectiveness.

He claimed that there was no need for any further stimulus as the “euro area economy is running at full capacity”. More on that claim later.

But the idea they are fermenting that interest rates should be increased soon and that the Euro economy is at full employment is an outrageous insult to the millions who remain unemployed!

This view was endorsed by the Austrian central bank governor and some other governing board members.

Mario Draghi responded to the question by acknowledging “the negative side effects on the people especially in those parts of the eurozone where the negative rates are being passed to corporate … depositors”.

He went on:

… the banks would like to have positive rates, unquestionably …

But he denied that the “negative rates would cause the collapse of the financial system because before getting there one has to look at other things of our banks.”

He said that the “certain structural weaknesses in the banking sector” in the Europe were not much to do with the negative deposit rates.

While his language was typically cautious, his statement on this was really reflecting on the poor management of the commercial banks, that have grown used to taking positions of excessive risk to grab profits out of the system, and, then, when the risk impacts and the strategies backfire, they put their hands out for public sector bailouts.

Privatise the gains, socialise the losses – the neoliberal way!

The two-tiered deposit approach

Accompanying the decision to go further into the negative range for the deposit rate, the ECB determined that:

In order to support the bank-based transmission of monetary policy, a two-tier system for reserve remuneration will be introduced, in which part of banks’ holdings of excess liquidity will be exempt from the negative deposit facility rate.

Both Japan and Switzerland have introduced tiered systems for bank reserves, although their particular schemes differ in design.

The bottom line is that once the deposit rate is negative, banks are then punished for holding excess reserves. The deposit rate has dropped from -0.4 per cent to -0.5 per cent.

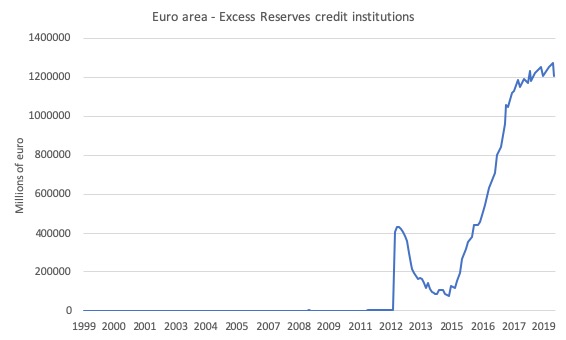

The following graph shows the evolution of excess reserves in the Eurosystem from its inception to July 2019. The early spike relates to the LTRO scheme and the subsequent decline was due to the fact that as financial stability improved the banks took advantage of ECB rule changes to pay back the refinancing liabilities ahead of schedule.

You can read about that in the ECB – Ad hoc communications.

The subsequent positive spike relates more to the continued ECB QE bond purchases.

One of the features of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) that is neglected by mainstream macroeconomics and monetary theory is the concept of bank reserves.

The mainstream treatment of bank reserves is mostly wrong.

Students learn that reserves are necessary for banks before they can make loans, as if they make the loans from the reserves – both propositions are not applicable to a real-world monetary system.

It is crucial to understand why, because that understanding allows us to correctly, in this case, appraise the ECB’s decision in relation to excess reserves.

Banks do not loan out reserves to retail customers.

Rather, bank reserves are an integral part of the ‘payments system’, where commercial banks use their exclusive accounts with their relevant central bank to settle transactions between themselves.

So, on any particular day, a multitude of transactions occur that have claims on funds between banks (for example, Bank A customer deposits a cheque from Bank B Customer which has to be cleared).

In some jurisdictions, the payments system has been referred to as the ‘clearing house’, harking back to when there were a lot of paper cheques that had to be reconciled each day.

Banks try to assess their daily reserve requirements but also, typically, will not choose to hold in excess of those clearing requirements because the reserves usually return less than a commercial return.

As we know, the deposit rate in the Eurozone, for example, is now -0.50 per cent. A ‘penalty’ rate on excess reserves.

Banks reserves also play a crucial role in the operations of central bank monetary policy. Reserves are provided exclusively by the central bank although that does not mean that the central bank can reasonably control their level.

I won’t go into the detail of how reserve accounts have broadened in some jurisdictions (for example, Britain) to include non-bank financial institutions. That sort of detail is unnecessary here.

Central banks use reserves management as a means of implementing their monetary policy – that is, maintaining a particular short-term policy interest rate.

So, typically, if there are excess reserves, which would otherwise drive the short-term rate down below the current policy rate, because the competitive process whereby banks try to loan those reserves to each other drives the rate down, the central bank would sell interest-bearing securities and drain the reserves.

And vice versa in the case of a shortage of reserves.

In the current post-GFC environment, central banks just pay a support rate on the reserves and this quells any incentive of banks to try to rid themselves of excess holdings.

It eliminates any need for the central bank to engage in traditional open-market operations (selling bonds and draining excess reserves or vice versa).

In this case, there is little difference between a reserve balance and a holding of short-term government debt – both are highly liquid (can be exchanged for cash at will) and both deliver some a return on holding (usually). The only real difference is the ‘name’ on the central bank account that records their existence.

The point to be clear about is that when MMT economists talk about the government currency-issuing capacity (which allows us to conclude that a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency), we are not talking about ‘money’ in the way people usually think about that term.

We are, instead, talking about the monopoly supply of bank reserves from the central bank and actual cash.

Many critics, who haven’t read our work closely enough, but conclude they are experts nonetheless, miss this point, when they claim that MMT is wrong in asserting that the government is the sole source of currency because banks creates deposits whenever they create loans.

The latter point is true – loans create deposits – which bears on the mistakes that mainstream monetary theory makes when it thinks deposits are needed before loans can be made.

But while banks can create ‘money’ in that broad sense, it is not the same ‘thing’ as currency creation.

Further, fiscal deficits push reserves up on a daily basis. This process helps us to understand why the claims that government borrowing pushes up interest rates and crowds out private investment is contrary to the reality.

If the central bank does nothing, then the pressure on interest rates from on-going deficits is downwards not upwards. Of course, the central bank might construe that the fiscal deficits are likely to be inflationary and push up rates through policy decisions.

But this is an entirely different argument than that based on ‘classical’ loanable funds reasoning, which Keynes negated convincingly in the 1930s, but which has resurfaced in this neoliberal era.

The other point to understand is that QE programs also increase bank reserves and contributing to the growing excess reserves in the system.

In this way, as we will see, there is a tension between a negative deposit rate policy stance, which penalises excess reserves, and QE which add to the excess.

The decision to introduce tiering reflects the fact that the various policy initiatives are not internally consistent.

The reduction in the deposit rate provides an incentive for banks to reduce their excess reserves.

But QE does the opposite because it works against the banks’ desire to run down reserves. In a QE system, the volume of reserves in the system are driven by the central bank – they are what we call supply-determined by the extent of the bond-buying program.

Without the QE system, the level of reserves in the system are at the call of the commercial banks with the central bank standing ready to supply the level demanded.

And so at present, if there are excess reserves in the banking system, the banks themselves cannot eliminate that, even though and individual bank can reduce their excess by pushing it onto another bank.

Do some arithmetic:

1. As at July 2019, the ECB reported that Excess reserves for credit institutions that are subject to minimum reserve requirements stood at 1,204,271 million euros.

2. The current penalty on those credit institutions for holding those reserves at the ECB would be 4,817 million euros over 12 months.

3. The new penalty (-0.05) will rise to 6,021 million euros.

4. Then add in the next round of QE (APP) and that penalty rises as more reserves are forced into the system by the ECB.

The tiering initiative is designed to reduce the costs on the banks and those with bank deposits. It means that the reintroduction of QE can go hand-in-hand with further movements into the red for the deposit rate without increasing the costs on the banks.

How?

The ECB Press Release (September 12, 2019) – ECB introduces two-tier system for remunerating excess liquidity holdings – noted that:

1. “All credit institutions subject to minimum reserve requirements … will be eligible for the two-tier system”.

2. “The two-tier system will apply to excess liquidity held in current accounts with the Eurosystem but will not apply to holdings at the ECB’s deposit facility.”

3. “The volume of reserve holdings in excess of minimum reserve requirements that will be exempt from the deposit facility rate – the exempt tier – will be determined as a multiple of an institution’s minimum reserve requirements.”

4. “The multiplier that will be applicable as of that maintenance period will be set at 6.”

5. “The exempt tier of excess liquidity holdings will be remunerated at an annual rate of 0%. The non-exempt tier of excess liquidity holdings will continue to be remunerated at zero percent or the deposit facility rate, whichever is lower.”

So do the sums again:

1. As at July 30, 2019, the excess reserves stood at 1,204.3 billion euros (Source).

2. The overall required reserves were 132 billion euros.

3. So 6 times 132 = 788.4 billion euros, which comprise the ‘exempt tier’ from the deposit rate of -0.5 per cent.

4. Thus, when the deposit rate was -0.4 per cent without the tiered approach, the penalty was 4.81 billion euros. With the tier at the deposit rate of -0.5 per cent, the penalty falls to 2.078 billion euros, a ‘saving’ of 2.738 billion euros.

And who benefits from the tiering initiative the most?

You got it – the German banks.

They account for around 35 per cent of the excess reserves in the Eurosystem.

French banks account for around 22.5 per cent of the excess, Dutch banks 12 per cent, then banks in Finland, Luxembourg and Spain.

I will write about the distribution of the excess reserves – the reasons and implications – in a later blog post.

But the point is that the German banks gain the most from the introduction of the two-tier system.

The period of fiscal dominance is approaching

The most important aspect of the ECB’s latest policy machinations is that they broaden the group of commentators and observers that are realising that monetary policy is being pushed further into the non-standard realm yet the effectiveness of these shifts is increasingly questioned.

The ECB has been forced by the straitjacket that the Treaty laws have placed Member State governments in to increasingly entertain so-called ‘non-standard’ monetary interventions.

We have an array of policy interventions that the ECB has introduced over the last seven years in a desperate attempt to maintain their price stability charter (they have failed) and stimulate the stagnant European economies (mostly failed).

While previous ECB policy positions were defined in terms of end-dates, the latest statement makes it clear that interest rates will remain low:

… until we have seen the inflation outlook robustly converge to a level close to, but below, 2%.

The most significant point that emerged from the ECB’s press releases and interviews last week, was Mario Draghi’s insistence that:

First of all let me start from one thing about which there was unanimous consensus, unanimity, namely that fiscal policy should become the main instrument … it’s quite clear that in order to raise demand in an effective … you’ve seen the language of the Introductory Statement after many years I think of being more or less the same about fiscal policy that has changed and I think there was complete agreement about that …

… it’s high time I think for the fiscal policy to take charge.

The ECB is thus now joining the chorus despite renegade statements from officials from the Bundesbank, Nederlandse, and the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, and others who continue to claim that the Eurozone is operating at full employment and that interest rates should rise not fall.

Bundesbank boss Jens Weidmann said in the Bild-Zeitung interview that it was crucial, in the words of Bild, that “monetary policy does not become harnessed to fiscal policy, because that jeopardises the central bank’s ability to keep prices stable.”

In his own words, he told the newspaper that:

The decision to buy even more government bonds has exacerbated this risk, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for the ECB to exit this policy.

The problem for the likes of Weidmann is that the horse bolted long ago and the evidence base fails (dramatically) to support his inflation obsession.

Conclusion

The most important aspect of the ECB decision was not the monetary policy changes, which will have relatively minor impacts on the real Eurozone economy.

The telling part of the whole episode was Draghi’s comments on fiscal dominance.

We are entering a new era where the neoliberal obsession with so-called monetary policy reliance is becoming increasingly discredited and exposed by the evidence base.

Fiscal dominance is approaching.

And the only body of work that has consistently argued for this approach to macroeconomic policy making has been Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) despite what the mainstream economists who are now starting to realise their reputations are in tatters might say.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It is interesting to parse Draghi’s words:

There is an evident contradiction between these two phrases. If it is high time for a rethinking of fiscal policy, why was this never hinted at in previous statements? Note that Draghi is on his way out, and probably feels freer to speak his mind. It is quite possible that the first statement under Lagarde’s leadership will see a return to the usual obfustication.

I love your optimism Bill.

Before fiscal policy rises from the ashes again the banks will need to be put back in their box and be bowler hat boring again. There’s not one political party in the West willing to take them on. On top of that they are in unelected positions which means they are difficult to remove and Simon Wren Lewis and his pals want to make it even more difficult to remove them and create even more unelected liberal technocrats and give them a fancy name.

The SNP gave me a little hope but it was false hope built in lies and deceit, as they have chosen the Irish model and to be at the heart of EU central.

Today where is the changes going to come from ? I simply do not see any political party willing to do what is needed.

“Fiscal dominance is approaching.” bill

Except the economy, due to government privilege such as deposit insurance instead of allowing the non-bank private sector to have inherently risk-free accounts at the Central Bank itself, runs on bank deposits, not on fiat*.

And the banks themselves create deposits when they “lend.” And those deposits created for the private welfare of the banks themselves and for the rich, the most so-called “credit worthy” , compete for real resources with deficit spending for the general welfare.

Yes, the monetary sovereign can (in principle) always out-bid the banks but at the cost of using up precious politically acceptable price inflation space.

And if unacceptable price inflation results what then? Taxes on the non-rich to curtail their consumption? Rather than eliminating privileges for the banks to curtail their ability to create deposits for private interests?

*Except for mere physical fiat, paper bills and coins.

Great.

If fiscal policy is coming now, maybe we should get some tattoos or something about the uselessness of monetary policy, so future generations won’t have to fall flat on their face for decades to learn that.

Andrew Anderson,

What is unacceptable price inflation? On what products? Why is there inflation?

There are many things that could cause what most people think is inflation. I think inflation and price rise are two different things. Inflation happens when economy gets too hot — supply cannot be met. Big deal! businessperson will build more supply over time. Not the end of the world.

Unemployment is far bigger issue in terms of social damage. Inability to confront climate change is far bigger issue.

When there is a price increase:

If businessperson is getting rich, that must mean the price inflation is caused by incomplete competition? right? Monopoly price, free lunch, charge w/e you want.

If houses are getting more and more expensive not by the cost of construction, then its a supply issue? right?

When you control the supply of houses, you can limit supply to jack the price up sky high (see Hong Kong).

When you control monopoly of a product, you can jack the price sky high.

People can’t find jobs do not care about inflation.

The word inflation just gets thrown out there too much nowadays.

I believe you can always find out what is causing “inflation” and arrest it with policies (public housing, price controls, take over monopolistic industries).

Of course, you run into the capital that has corrupted government and beaten unions down to a pulp so its a very powerful entity that has given us thorough neoliberalism in the first place.

All the framing and political limits are set by these people, so what we don’t dare to think outside the box these people have set us.

Anyway, as long as people can find jobs, I don’t really find some inflation is a big issue.

Only rich people and people who sit on their butts care about inflation thats what i feel like.

What destroy my own finances is the ridiculous rent, taxes, insurance and low pay here in Los Angeles, not the 2 percent inflation w/e.

“But while banks can create ‘money’ in that broad sense, it is not the same ‘thing’ as currency creation.” In fact, so-called bank money created by loans (and thus inherently linked to private debt) would seem to be the polar opposite of federal currency creation ex nihilo via governmental spending decisions. MMT must continue to highlight this essential difference, obscured by the artificial linkage of federal currency to the sale of federal bonds, which is itself but a prime example of the deliberate misapplication of household economy accounting to currency-sovereign nations. Until this essential distinction between federal currency and bank money sinks home, average citizens will tend to view increased federal spending in the same manner as extravagant household spending, which they know only drives families deeper into debt.

While I like Bill’s articles I have come to the conclusion that it is all too hard for the average Jo Blow. We have to have a one liner to say to the Bus driver, the Butcher the shop assistant when they say ‘ my taxes are paying for that and I don’t like it’. When they say that they are not asking for a conversation. I am working on that one liner!! It is hard because such a one liner must give food for thought and hope

I propose this one liner. Feel free to improve it.

“Think about this, the US Gov. {insert any sovereign nation} has as much need for dollars from tax revenue before it can spend them as it needs T-Bills and Bonds to be cashed in before it can sell more Bonds. Therefore, the US Gov. is not at all like a family, it’s the opposite of a family, in fact.”

@Patricia

I feel your pain! My personal favorite one-liner is

“Money isn’t wealth; it is just a way of keeping score. Taxes are just a way of resetting the scoreboard so it’s worth everyone’s time to play again tomorrow. The rich have nothing the rest of us need”.

“And who benefits from the tiering initiative the most?

You got it – the German banks.”

Well, color me surprised…

“the conservative daily German newspaper Bild-Zeitung”

This is akin to calling the Koch bros. succesful businessmen and philantropists. BILD is a fascist rag, but Bill is to civil to call it like it is. Note how the German tampering with the European finance system to benefit their banks is somehow spun into an aggression by a foreigner, a southerner (!), on the diligent and responsible German saver.

Indeed, I agree that fiscal supremacy is around the corner. However, it is but a tool that can be used for the most nefarious of purposes. Taking the increasingly de-democratization of European governments and the ever increasing influence of big money on them, I would not be surprised to see a neo-fascist system arise from the ashes of neoliberalism. In fact, I often think it was the purpose all along. The alliance of oligarchs and plutocrats actually need a new FDR and a “new new deal” that buys their system more time. In their arrogance and shortsightedness, the fail to grasp that they have reached a “gatopardo moment” (in allusion to G. di Lampedusa’s novel). In the afterwar scenario of that novel, an aristocrat makes the point that “everything has to change so all remains the same”. This side of the pond, barring the miraculous appearance of a European-scale Bismarck who succesfully cajoles the capitalist elite into a new “Revolution von oben”, I’m afraid the situation will be escalated yet again to a point where the question will be “socialism or barbarism”.

History does not necessarily repeat itself but, according to Mark Twain, it often rhymes and that would be bad enough.

@Patricia, Steve and Andrew

Sadly, the best one-liner I have heard in this regard comes form (99.9%) Dick (and only traces of) Cheney:

“Deficits don’t matter.”

I like to go with:

“Money isn’t wealth and wealth isn’t happiness. Happiness is happiness.”

But it is not only not that poignant and a bit too “new age”, it isn’t even a one-liner 🙁

I think Stephanie Kelton goes with “You say we think money grows on a magic tree, but you think it grows on rich people” or something. While rather good, it requires a certain degree knowledge about government central bank interactions and the mechanics behind corporation’s investments to fully grasp.

I’m remain open to suggestions.

@Patricia, Steve and Andrew

Sadly, the best one-liner I have heard in this regard comes form (99.9%) Dick (and only traces of) Cheney:

“Deficits don’t matter.”

I like to go with:

“Money isn’t wealth and wealth isn’t happiness. Happiness is happiness.”

But it is not only not that poignant and a bit too “new age”, it isn’t even a one-liner 🙁

I think Stephanie Kelton goes with “You say we think money grows on a magic tree, but you think it grows on rich people” or something. While rather good, it requires a certain degree knowledge about government central bank interactions and the mechanics behind corporation’s investments to fully grasp.

I remain open to suggestions.

Sorry for the double-post 🙁

It’s tough. One line won’t do it all; the first line has to be a grabber.

The government creates money. The government doesn’t have to collect money.

The government has valid reasons to collect money, but not because they’re helpless without collecting it.

All that money for QE and Tarp? The U.S. government created it. Who else could? The banks? They were broke. That’s why they needed QE and TARP.

?? Might work.

@Patricia Smith:

You’ve already had some great answers. This one might be by way of a followup:

“Money isn’t the issue; real resources are the issue”.

and the good old standby, especially in the UK where memories of Mrs Thatcher, the ever-prudent housewife-PM, are etched deep:

“The government is not a household”

or

“Government finances do not work like household finances”.

Hermann wrote:

‘Taking the increasingly de-democratization of European governments and the ever increasing influence of big money on them, I would not be surprised to see a neo-fascist system arise from the ashes of neoliberalism. In fact, I often think it was the purpose all along. The alliance of oligarchs and plutocrats actually need a new FDR and a “new new deal” that buys their system more time.’

Yes, this is a real threat due to the ghastly failure of the Left. here in the UK what you write is already well in progress with polls showing significant support for the Tories and Brexit Party while Labour squabbles over the ‘remain’ position with Corbyn desperately trying to create unity around underlying dynamics which is like shouting in an anechoic chamber because of the Leave/Remain polarisation.

Meanwhile, the Lib Dems try to play the middle class, prtraying themselves as the ‘reasonable centre’ whilst being an ‘extreme centre’ (to use Tariq Ali’s phrase).

Things don’t look good!

@ Patricia Smith

I’m sorry but IMHO your quest no matter how worthy is futile, and I would argue that the suggestions you’ve had are evidence for that opinion.

Bear with me please.

MMT analyses and explains the inner dynamics of a fiat monetary system. That is by definition a conceptualisation. Therein lies your problem: although those dynamics’ *effects* manifest themselves in the real world they themselves inhabit only the world of ideas.

A good analogy is to be found in the field of thermodynamics. In both cases alike, induction into the respective theories’ elucidation *of what is really going on behind the surface-appearance* is a prerequisite for being able to grasp their counter-intuitive insights and thereby come to “own” them. For instance, the Second Law told its original dumbfounded Victorian audience that without a flow of heat from hot to cold their mighty steam-engines would be no more use than piles of scrap-iron, because there is nothing to physically drive the mechanism except the flow of heat-energy and in order for heat to flow it must have a path from hot to less-hot terminating in an ultimate escape (the cold sink). Thus it was not the palpable supply of steam from its boiler which – as was “obvious” to any contemporary observer – was the fundamental source of its power but the IMPALPABLE cold sink into which the waste heat was dumped without whose – albeit invisible – presence (in the form of the surrounding cooler atmosphere) no heat-engine can work.

I suggest that that provides a useful parallel for the functioning of taxation seen through the MMT lens. Just like the steam-engine the monetary system can’t do its job – which is to optimise the use of a nation’s available resources including labour – in the absence of some means (a “drain”) for evacuating any inflationary pressure which might otherwise build up in the system, and taxation is one of the only two means for doing that (the other being to reduce government spending)

No more than the inner working of a thermodynamic system (in the form of a steam-engine in this example) could be apprehended *merely through intuition * by the ordinary person then, so neither can the primary purpose of taxation within a fiat monetary system being *to take money out* of the economy be apprehended in like fashion by an ordinary person today. In fact the idea is completely *counter*-intuitive.

There are no short-cuts to understanding counter-intuitive concepts; that takes effort (assuming the desire and ability to learn). Slogans and catch-phrases will never do it.

That’s my opinion FWIW. Others may disagree.