Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – July 27-28, 2019 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The immediate impact on the net worth of the non-government sector does not vary if the government issued bonds to exactly match ($-for-$) the increase in its net public spending or chooses not to so match.

The answer is True.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The textbooks fail to convey an understanding that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

They claim that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a fiscal deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

So in terms of the specific question, you need to consider the reserve operations that accompany deficit spending. Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management as explained above. But at this stage, M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. In other words, fiscal deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

You may wish to read the following blog posts for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

The wider the spread between the price the central bank sets on the reserves it provides the commercial banks on demand (so-called penalty rates) and the target policy rate the more difficult it becomes for the central bank to ensure the quantity of reserves is appropriate for maintaining its target policy rate.

The answer is True.

The facts are as follows. First, central banks will always provided enough reserve balances to the commercial banks at a price it sets using a combination of overdraft/discounting facilities and open market operations.

Second, if the central bank didn’t provide the reserves necessary to match the growth in deposits in the commercial banking system then the payments system would grind to a halt and there would be significant hikes in the interbank rate of interest and a wedge between it and the policy (target) rate – meaning the central bank’s policy stance becomes compromised.

Third, any reserve requirements within this context while legally enforceable (via fines etc) do not constrain the commercial bank credit creation capacity. Central bank reserves (the accounts the commercial banks keep with the central bank) are not used to make loans. They only function to facilitate the payments system (apart from satisfying any reserve requirements).

Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the requirements from other sources (other banks) then the central bank has to provide them. But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to the deposit creation (via the loan).

Fifth, if there were too many reserves in the system (relative to the banks’ desired levels to facilitate the payments system and the required reserves then competition in the interbank (overnight) market would drive the interest rate down. This competition would be driven by banks holding surplus reserves (to their requirements) trying to lend them overnight. The opposite would happen if there were too few reserves supplied by the central bank. Then the chase for overnight funds would drive rates up.

In both cases the central bank would lose control of its current policy rate as the divergence between it and the interbank rate widened. This divergence can snake between the rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves (this rate varies between countries and overtime but before the crisis was zero in Japan and the US) and the penalty rate that the central bank seeks for providing the commercial banks access to the overdraft/discount facility.

So the aim of the central bank is to issue just as many reserves that are required for the law and the banks’ own desires.

Now the question seeks to link the penalty rate that the central bank charges for providing reserves to the banks and the central bank’s target rate. The wider the spread between these rates the more difficult does it become for the central bank to ensure the quantity of reserves is appropriate for maintaining its target (policy) rate.

Where this spread is narrow, central banks “hit” their target rate each day more precisely than when the spread is wider.

So if the central bank really wanted to put the screws on commercial bank lending via increasing the penalty rate, it would have to be prepared to lift its target rate in close correspondence. In other words, its monetary policy stance becomes beholden to the discount window settings.

The answer is True because the central bank cannot operate with wide divergences between the penalty rate and the target rate and it is likely that the former would have to rise significantly to choke private bank credit creation.

You might like to read this blog for further information:

- US federal reserve governor is part of the problem

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 3:

Assume that a national is continuously running an external deficit of 2 per cent of GDP. In this economy, if the private domestic sector successfully saves overall, we would always find:

(a) A fiscal deficit.

(b) A fiscal surplus.

(c) Cannot tell because we don’t know the scale of the private domestic sector saving as a % of GDP.

The answer is Option (a) – A fiscal deficit.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

Refreshing the balances (again) – we know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

To refresh your memory the sectoral balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all taxes and transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total taxes and transfers (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAB] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down. The reference to the specific 2 per cent of GDP figure was to place doubt in your mind. In fact, it doesn’t matter how large or small the external deficit is for this question.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) seeks to increase its saving ratio and is successful in doing so. Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract – output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public fiscal balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its saving ratio then the contracting income will clearly push the fiscal position into deficit.

So if there is an external deficit and the private domestic sector saves (a surplus) then there will always be a fiscal deficit. The higher the private saving, the larger the deficit.

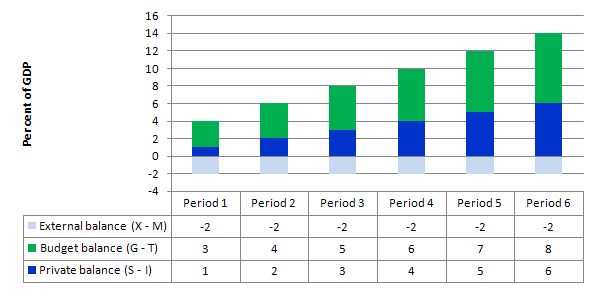

The following Graph and related Table shows you the sectoral balances written as (G-T) = (S-I) – (X-M) and how the fiscal deficit rises as the private domestic saving rises.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

In his response to Question 1, Bill writes, “The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate ….” And in his response to Question 2, Bill writes, “Where this spread is narrow, central banks “hit” their target rate each day more precisely than when the spread is wider.”

The target interest rate in question is, if I understand correctly, the rate at which banks lend funds to one another overnight to that borrowing banks can satisfy reserve requirements.

I find that I often have trouble articulating exactly why the central bank is so concerned with targeting this rate on a daily basis.

* Is it part of its legislative mandate?

* Is this concern with hitting a target rate something the central bank has always been very concerned with, or is it something that has evolved over time?

* What would be the consequences if the central bank were unable to “hit” its target interest rate? Who outside the central bank would care?

I find myself unable to answer those questions in ways that satisfy myself or other people.

I was thinking about they way reserves system works as you describe it, and I was trying to understand what insolvency means for a bank. If the central bank will always create enough reserves to fund the loans a commercial bank makes, then doesn’t a commercial bank always have some kind of guarantee? I am pretty sure this is wrong, but I haven’t gone through the process to figure out why (e.g. if the commercial bank has a high enough proportion of bad debts)

From my perspective, I think we just have to get it right, even if I don’t happen to understand the full significance on the 250 basis points fed funds rate.

It’s giving banks free money. They don’t need it to create credit anyway. Probably funds those bankers making 100K while scientists bust their behinds all across this country making 30K to 50K.

Whatever credit they create is largely asset price inflation and not for capital formation if i’m not wrong.

Randall Wray has also mentioned that it is a policy choice.

Probably doesn’t really matter much in the grand scheme of things if fed funds rate can’t be hit today. Try again tomorrow.

Commercial banks don’t have guarantees in the sense of infinite reserves. I think mortgages are backed by the fed so banks are guaranteed in that sense that the FED will bail bad mortgages out.

Reserves are for the payment system. Reserves do NOT fund bank loans at all. 3 things limit credit-creation:

1. If the bank wants to make money.

2. If the customer wants a loan.

3. If the customer is creditworthy.

Then the success and the degree of success of the bank operation depends on:

1. Whether the customer is able to pay off the loan.

2. How cheap the bank can get reserves.

A bank’s equity to the credit it creates is very small. so a bank goes insolvent even if a small portion of its loans go bad because it will have to pay out of its own pockets

Consider getting your hands on the macroeconomics textbook. It lays out everything pretty clearly.

If i’m wrong in any way, someone please don’t hesitate to point it out.

@vote for pedro

The cb’s main purpose apart from inflation- and interest-control is making sure the paymentsystem works including lending reserves. Insolvency-risks involves lack of shareholder-capital or not high enough equity. If other banks think another bank is at risk they demand higher interest when lending. Banks are engaged with each other in many ways, not only through their daily clearing-operations. That is why the interbank-rate would rise if there is a crises-situation. If a particular bank is no longer thrusted the cb has to step in. Depending on the situation several things could happen. Usually the bank will get cb-finance but at a new higher rate-level. During the GFC thd US FED swapped bad assets against good. This not working for non-securitized assets. Here the bank normally have to emitt new shareholder-capital. Insolvency due to lack of liquidity is the first sign of problems in businesses generally. Corporate reconstructions involves selling of (good) assets and even closing of other business. In the US the SEC has the oversight responsibility over banks wich includes monitoring their minimum equity-ratios etc.

@Tom

Banks create deposits by making a custom-loan. A deposit sits on the right side of the balance-sheet (the passive side ). It is the bank’s debt, aka what the bank owns their customer. On the active left side we find the bookvalue of the customer-loan. The bank’s asset.

When the customer wants his loan payed out to another bank the transaction will be cleared together with all other transactions with corresponding banks. The sending bank will have it’s deposit-debt changed to a new debt when financing the payout. Normally this is done in the interbank-market. The cb will overwatch the level of necessary reserves with respect to monetary-pollicy and target-rate.

In normal times when new financial assets (cash from abroad or government deficits) enters the banksystem this will influence interest-rates due to cash-deposits. But interbankcash can change quickly from other internal activities like stockmarket-selloffs etc.

@Tom

Corporations have their cash in banks and banks have their cash at the cb. Net deposits by banks at the cb is netreserves. Normally banks does not want to have cash at the cb because it earns no interest (except in ior-times). Banks invest in the interbank overnight market instead (based on their cashmanagement-planning). If there is a deficit in the daily interbankclearing (normally managed in a cb-computersystem) banks that do not have enough cash get their account at the cb credited with the deficit-amount.

Forgot to say that for every net credit/loan that stays within the national banksystem increases the moneysupply (M2 i.e) aka cash-deposit.

@mr Keenan

The target-rate is a market-management system. The cb use the target-rate to signal changes in their intentions. A change therefore affects all businesses (and households) that needs capital! The financial markets are affected instantly in profits and losses on longer durations. Unintented deviations from target-rate can also cause market-speculations which is not proactive.

Hitting the target-rate on a daily basis is a part of cb’s Open Market Operations, repo-market i.e. Buy doing this they will better understand and manage the market. Instead of being unaware of what is going on.

Managing supply and demand is managing prices and price-expectations.

I’d like to attempt an answer to your question James (July 27 at 22:12) . Please keep in mind that this probably differs from what Bill would say. Also keep in mind that it is often more difficult to speculate ‘why’ someone does something than to observe that they actually do do that something.

So why do central bankers try to hit a target interest rate? It is because they believe that the economy is very responsive to changes in that rate and that it helps determine the rates of both inflation and unemployment. And sometimes, the foreign exchange value of the currency. MMT says that they mostly believe wrongly- especially when the central bank in question is part of a sovereign currency issuing government that does not try to fix its currency to any commodity or other currency.

Law in specific countries will vary, but this is what the US Fed says about itself and the goals it has been given by the US Congress-

“The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. It performs five general functions to promote the effective operation of the U.S. economy and, more generally, the public interest. The Federal Reserve

-conducts the nation’s monetary policy to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates in the U.S. economy;

-promotes the stability of the financial system and seeks to minimize and contain systemic risks through active monitoring and engagement in the U.S. and abroad;

-promotes the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions and monitors their impact on the financial system as a whole;

-fosters payment and settlement system safety and efficiency through services to the banking industry and the U.S. government that facilitate U.S.-dollar transactions and payments; and

-promotes consumer protection and community development through consumer-focused supervision and examination, research and analysis of emerging consumer issues and trends, community economic development activities, and the administration of consumer laws and regulations.”

So- there is no law that says the Fed must specifically target any interest rate. There are laws that instruct the Fed to try to achieve certain goals. But by observing the Fed’s conduct, it is very fair to say that they seem to consider the Fed funds rate as a primary tool to achieve those goals. MMT points that out. MMT also says that the central bank, as an agent of the currency issuing government, will always, always be able to hit whatever target interest rate it desires. So there really is no question about what the consequences of missing it would be- it won’t happen.