In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Fiscal space has nothing to do with public debt ratios or the size of deficits

The Project Syndicate is held out as an independent, quality source of Op Ed discussion. When you scan through the economists that contribute you see quite a pattern and it is the anathema of ‘independent’. There is really no commentary that is independent, if you consider the term relates to schools of thought that an economist might work within. We are all bound by the ideologies and language of those millieu. So I assess the input from an institution (like Project Syndicate) in terms of the heterodoxy of its offerings. A stream of economic contributions that are effectively drawn from the same side of macroeconomics is not what I call ‘independent’. And you see that in the recurring arguments that get published. In this blog post, I discuss Jeffrey Frankel’s latest UK Guardian article (August 29, 2018) – US will lack fiscal space to respond when next recession comes – which was syndicated from Project Syndicate. Frankel thinks that the US is about to experience a major recession and that its government has run out of fiscal space because it is not running surpluses. We could summarise my conclusion in one word – nonsense. But a more civilised response follows.

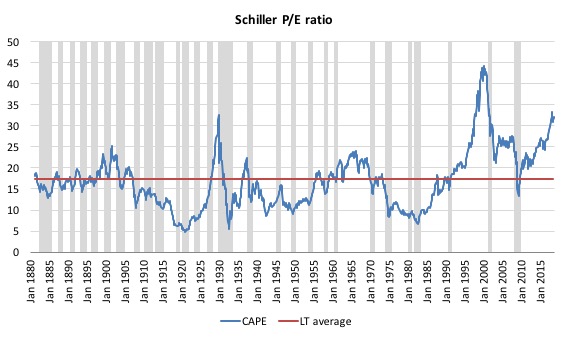

In 1987, American economists John Y. Campbell and Robert Schiller introduced the – Cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE) as a guide to assessing whether the US equities market is overpriced or not (the long-term average of 16 is considered the threshold).

Their research found that “the lower the CAPE, the higher the investors’ likely return from equities over the following 20 years.”

Schiller refined the measure and it became known Schiller P/E (aka CAPE).

By construction, the CAPE allows a comparison between the current market price and itsinflation-adjusted, average performance over a ten-year period.

Schiller’s rule of thumb is that when the ratio exceeds 25, a “major market drop” follows – Schiller’s 2000 book Irrational exuberance was a reflection of this observation.

The provenance of the CAPE goes back to the work of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd published in their 1934 book – Security Analysis.

As an aside, I drew on the work of Benjamin Graham in my early development of the buffer stock employment idea (now called the Job Guarantee).

His 1937 book Storage and Stability: A Modern Ever-normal Granary, New York: McGraw Hill provided some great insights into buffer stocks schemes and price stability – in his case, for agricultural products.

The CAPE is considered a flawed measure though because of the way it defines earnings (for example, accounting changes to definitions, the exclusion of retained earnings), which tends to inflate the ratio.

But the technicalities of that debate are not what this blog post is about.

The following graph shows the CAPE ratio calculated by Robert Schiller from January 1880 to August 2018. The long-term average (17.48) is the red line and the gray bars are the NBER recession periods (peak to trough).

As you can see the P/E ratio, which in August 2018 was 32.29, is now well above its long-term average and has been since August 2009.

It hasn’t reached the December 1999 peak (of 44.20) – the ‘Dot.com bubble’ – but it is certainly well above the pre-GFC levels.

What does this mean?

Well according the Harvard economist Jeffrey Frankel in his latest UK Guardian article (August 29, 2018) – US will lack fiscal space to respond when next recession comes – the level of the CAPE is “one possible trigger for a downturn in the coming years is a negative shock that could send securities tumbling”.

Which means? Share prices will fall.

Is the relatively high CAPE ratio a sign of ‘irrational exuberance’ which Alan Greenspan considered marked the Dot.com boom and bust? That looks doubtful to me.

There is no frenzied share buying going on. If you were an investor in that market then you realise the shares are over-priced, which is a relative term, and just means for anyone who knows what they are doing that their expected returns will be lower than if the CAPE ratio was lower.

But that is relative too – the returns on other financial assets (government bonds, etc) are equally low.

So the combination of the technical flaws in the CAPE ratio (overstating the true P/E ratio) and the overall state of the investment markets indicates to me that there is no major collapse coming from that quarter.

The graph tells us that the CAPE ratio falls during recession, which is unsurprising but there is no consistent eveidence that it leads a recession (that is, could cause it).

It is possible that investors are heavily leveraged and if the PE falls they cannot pay up and the banks enter crisis. But I think the GFC taught us that treasury departments and central banks have all the capacity they need to prevent that sort of financial kerfuffle spreading more broadly.

Which brings me to the next and substantive point.

Jeffrey Frankel believes that one source of shock or another (share market collapse, trade war, Turkey spreading, Italy, China, etc) will trigger a new crisis in the US economy.

He concluded:

Whatever the immediate trigger, the consequences for the US are likely to be severe, for a simple reason: the US government continues to pursue procyclical fiscal, macroprudential, and even monetary policies. While it is hard to get countercyclical timing exactly right, that is no excuse for procyclical policy; an approach that puts the US in a weak position to manage the next inevitable shock.

There are several recurring themes in that paragraph:

1. What is a pro-cyclical policy? Does counter-cyclical policy require fiscal deficits/low interest rate in a downturn and fiscal surpluses/high interest rates in an upturn?

2. How can the US policy institutions – Treasury Department and Federal Reserve Bank – be in a “weak position to manage the next inevitable shock”? Is there any meaning to the term “weak”? If so, what is a ‘strong’ position?

The title of Frankel’s article should tell you where he stands.

He is one of those mainstream macroeoconomists (supervised by Rudiger Dornsbusch) that believes there is a time for fiscal stimulus, when monetary policy hits the zero-bound (yes, that!) but that essentially at other times, monetary policy should be firmly in charge of counter-stabilisation duties.

In that context, he defended President Obama’s fiscal stimulus in 2009 but now thinks that the fiscal party has gone on for too long and that Trump is setting the US economy up to fail.

He has been an advisor the Clinton Administration, which also should tell you something.

He has long claimed that policy makers pursuing ‘Keynesian’ fiscal positions fell into disrepute because (Source):

… politicians often failed to time countercyclical fiscal policy – “fine tuning” – properly. Sometimes fiscal stimulus would kick in after the recession was already over. But that is no reason to follow a destabilizing pro-cyclical fiscal policy, which piles spending increases and tax cuts on top of booms, and cuts spending and raises taxes in response to downturns.

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy worsens the dangers of overheating, inflation, and asset bubbles during booms, and exacerbates output and employment losses during recessions, thereby magnifying the swings of the business cycle.

He also wrote in a 2013 Symposium published in the Spring issue of The International Economy – his response to the question “Does Debt Matter?” – is HERE.

He wrote on public debt in the context of the Rogoff-Reinhart 90 per cent threshold that was prominent during the crisis, until their Excel incompetence (at least) was exposed, that:

Yes, debt matters. I don’t think I know of anyone who believes that a high level of debt is without adverse consequences for a country. There is no magic threshold in the ratio of debt to GDP, 90% or otherwise, above which the economy falls off a cliff. But if the debt/GDP ratio is high, and especially if the country’s interest rate is also high relative to its expected future growth rate, then the economy is at risk. One risk is that if interest rates rise or growth falls, the economy will slip onto an explosive debt path, where the debt/GDP ratio rises without limit. In the event of such a debt trap, the government may have no choice but to undertake a painful fiscal contraction, even though that will worsen the recession. (The resulting fall in output can even cause a further jump in the debt/output ratio, as it has in the periphery members of the eurozone over the last few years.)

So before I consider those two themes above, you can see the problem he has.

The previous paragraph comes down to this:

1. Debt matters.

2. Why? Because in a recession debt will rise as governments (under current arrangements match their deficit spending with debt-issuance).

3. Why is that a problem?

4. Debt matters.

Of course, the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) response (the purist one) is that currency-issuing governments such as the USA do not have to issue any debt when they are running fiscal deficits.

But that ignores the institutional realities.

Taking reality into account, however, doesn’t alter the conclusion.

Central banks can effectively buy whatever volume of public debt they choose and keep interest rates around zero for as long as they like no matter the quantity of public debt (in absolute or relative terms (to GDP)).

The private bond markets have no traction in those cases.

I last considered that sort of situation in this blog post – The bond vigilantes saddle up their Shetland ponies – apparently (February 12, 2018).

I concluded:

1. The private bond markets have no power to stop a currency-issuing government spending.

2. The private bond markets have no power to stop a currency-issuing government running deficits.

3. The private bond markets have no power to set interest rates (yields) if the central bank chooses otherwise.

4. AAA credit ratings are meaningless for a sovereign government – they can never run out of money and can set whatever terms they want if they choose to issue bonds.

5. Sovereign governments always rule over bond markets – full stop.

I also updated my analysis of central bank holdings of US governemtn debt in this blog post – Central banks still funding government deficits and the sky remains firmly above (August 23, 2017).

Here is the latest update.

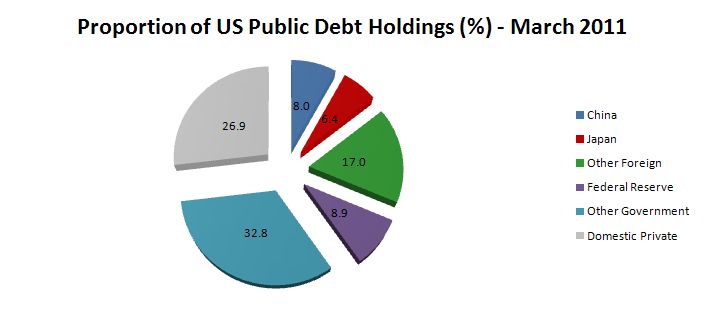

First, cast your mind back to March-quarter 2011.

The following pie-chart shows the proportions of total US Public Debt held by various categories as at the March-quarter 2011.

The government sector held about 42 per cent of its own debt. These holdings were either in the intergovernmental agencies or the US Federal Reserve Bank.

The US Federal Reserve held 8.9 per cent of total US public debt. Its total holdings were around $US 1,274.3 billion.

The three largest foreign US debt holders at the March-quarter 2011 were China (8 per cent), Japan (6.4 per cent) and Britain (2.3 per cent). The total foreign held share was equal to 31.4 per cent.

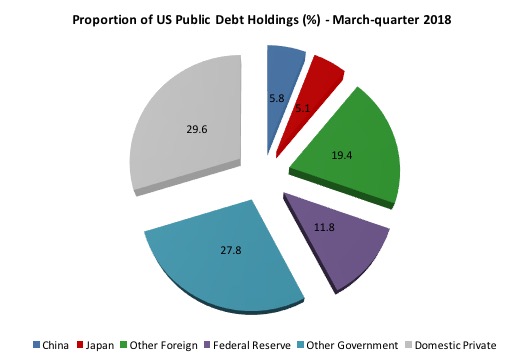

Now, to the most recent data – March-quarter 2018 – some 7 years later. Some of the data, by the way, is available for the June-quarter 2018, but only the complete set required for this analysis is available for the March-quarter.

As at the end of March 2018, there were $US21,089.9 billion Federal Securities outstanding.

These were broken down into:

1. Privately held – $US12,360.60 billion (60.3 per cent of total).

2. Federal Reserve and Intragovernmental holdings (SOMA and Intragovernmental Holdings) – $US8,132.10 billion (39.7 per cent of total).

3. Foreign and international – $US6216.60 billion (29.5 per cent of total) – of which $US4049.1 billion held by Foreign Official institutions (central banks etc).

A comparison of movements over the last 7 or so years in the composition of US Treasury debt holdings is provided by the two pie charts

1. The government sector overall held about 39.6 per cent of its own debt in the March-quarter 2018. This is slightly down on the proportions held in the March-quarter 2011 (40.3 per cent).

2. These holdings were either in the intergovernmental agencies (27.8 per cent) or the US Federal Reserve Bank (11.8 per cent). The central bank has increased its holdings over the period in question (though proportionally now holds less).

3. The Chinese holdings were around 5.8 per cent of the total and hardly consistent with the rhetoric that China was bailing the US government out of bankruptcy. These holdings have fallen in recent years.

4. The three largest foreign US debt holders at the March-quarter 2018, were China (5.8 per cent); Japan (5.2 per cent) and Ireland (5.1 per cent).

The recent history provides a very important lesson. The US central bank can initiate very dramatic shifts in the mix of debt holders whenever it chooses.

This means that the central bank can always purchase any debt that the private sector chooses not to purchase via the primary auctions.

There is never a reason for US government bond yields to rise above a level that the government considers to be accpetable.

Lets move on.

In this blog post – The full employment fiscal deficit condition (April 13, 2011) – which I consider to be core MMT, I showed the conditions that determine the fiscal deficit, once the government assumes its responsibility to achieve and sustain full employment.

The lessons, in summary are:

1. A macroeconomy is in a steady-state (that is, at rest or in equilibrium) when the sum of the injections equals the sum of the leakages. The point is that whenever this relationship is disturbed (by a change in the level of injections, however sourced), national income adjusts and brings the income-sensitive spending drains into line with the new level of injections. At that point the system is at rest.

2. The injections come from export spending, investment spending (capital formation) and government spending.

3. The leakages are household saving, taxation and import spending.

4. An economy at rest is not necessarily one that coincides with full employment.

5. When an economy is ‘at rest’ and there is high unemployment, there must be a spending gap given that mass unemployment is the result of deficient demand (in relation to the spending required to provide enough jobs overall).

6. If there is no dynamic which would lead to an increase in private (or non-government) spending then the only way the economy will increase its level of activity is if there is increased net government spending – this means that the injection via increasing government spending (G) has to more than offset the increased drain (leakage) coming from taxation revenue (T).

So in sectoral balance parlance, the following rule hold.

To sustain full employment the condition for stable national income defines what I named the Full-employment fiscal deficit condition:

(G – T) = S(Yf) + M(Yf) – I(Yf) – X

The sum of the terms S(Yf) and M(Yf) represent drains on aggregate demand when the economy is at full employment and the sum of the terms I(Yf) and X represents spending injections at full employment.

If the drains outweigh the injections then for national income to remain stable, there has to be a fiscal deficit (G – T) sufficient to offset that gap in aggregate demand.

If the fiscal deficit is not sufficient, then national income will fall and full employment will be lost. If the government tries to expand the fiscal deficit beyond the full employment limit (G – T)(Yf) then nominal spending will outstrip the capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output and while income will rise it will be all due to price effects (that is, inflation would occur).

What that means in relation to the issues I identified above is that there is a difficulty in defining pro-cyclicality in terms of a given fiscal balance.

It is nonsensical to say a fiscal surplus is always pro-cyclical and a deficit is always counter-cyclical. It all depends on the spending and saving patterns of the non-government sector.

We can only really appraise the impact of the fiscal balance in terms of changes at specific points in the cycle.

So if an economy was at full employment and the fiscal deficit was, say 2 per cent of GDP and that satisfied the condition specified above.

That is not a pro-cyclical position even if the economy is growing – it is maintaining a steady-state growth path.

Should the government, with no other changes evident, increase its net spending to say 3 per cent of GDP, under those circumstances, we might consider that a pro-cyclical policy change because it is pushing the cycle beyond its full employment steady-state growth path.

So the fact there is a fiscal deficit coinciding with strong GDP growth should not be taken as a case of irresponsible and dangerous policy.

What about running surpluses when recovery is apparent?

The same logic holds. It might be that the non-government spending and saving decisions drive overall spending so fast that total spending then starts to outstrip capacity.

Then, to restore the full employment steady-state (and this also requires stable inflation), the fiscal stance has to contractionary – which might require a fiscal surplus.

For example, nations such as Norway will typically solve the Full-employment fiscal deficit condition with a fiscal surplus given how strong their external sector is (energy resources).

The second issue relates to Jeffrey Frankel’s notion of ‘fiscal space’.

I considered that issue in these blog posts:

1. Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 (June 15, 2009).

2. Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 (June 16, 2009).

3. Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 (June 17, 2009).

Frankel claims that the:

The US deficit is being blown up on both the revenue and expenditure sides … As a result, when the next recession comes, the US will lack fiscal space to respond.

The next recession, when it comes, will coincide with millions of workers in need of jobs, capital equipment lying idle, and other productive resources looking for a buyer (user).

That is what fiscal space relates to in a modern monetary economy.

It has nothing to do with what the current fiscal balance is or has been and what the current public debt ratio is or has been.

A sovereign government can purchase any idle resources that are for sale in its own currency, including all idle labour.

That is the fiscal space the US will have.

And, it can never run out of funds to do that.

So a past deficit poses no particular constraints on what the US government can do in the future, except to say that if the deficit has been properly calibrated to satisfy the Full-employment fiscal deficit condition then there will be less to do should the private sector contract.

The rest of Frankel’s article is irrelevant to this discussion.

The questions that the US policy makers have to answer are:

1. How close the economy is to being at full capacity – labour, capital and other productive resources.

2. If, it is, is the current net public spending position driving total spending beyond the Full-employment fiscal deficit condition.

My assessment of Question 1 is that there is still some idle capacity in the US economy. Just look at wages growth and the broader indicators like participation rates.

There is a massive public infrastructure shortfall – in terms of quality and scope.

Inflation is benign as is wages growth.

Conclusion

Frankel’s argument is like a cracked record. It just keeps being recycled by mainstream economists as if it is common sense.

The facts are:

1. We can never conclude that the coexistence of a fiscal deficit and strong growth requires the government push back into surplus. Sometimes yes, usually no.

2. Fiscal space has nothing to do with what the current fiscal balance is or has been and what the current public debt ratio is or has been.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Countdown to when you change the title of this post to:

Fiscal space has nothing to do with public debt. (Or something similar)

In 3..2…1

Bill, you know sarcastic titles don’t work on the internet and you end up having to change the title once people start sharing your articles en mass because you end up spreading the opposite of what your article is saying (since people don’t read and they don’t get sarcasm)

You had to change a recent title as you recall for the same reason.

🙂

Dear Charles Como (at 2018/08/30 at 9:33 pm)

There you go.

Fair comment.

best wishes

bill

“1. What is a pro-cyclical policy? Does counter-cyclical policy require fiscal deficits/low interest rate in a downturn and fiscal surpluses/high interest rates in an upturn?”

The second sentence does not make much sense. Frankel, in the article, seems to take a simple approach to defining pro- and counter-cyclicality in terms of negative and positive correlations. So, if a given process is increasing in value, then a counter-cyclical process will be going in the opposite direction. They are negatively correlated. When pro-cyclical processes are both either increasing or decreasing together, they are positively correlated.

As your subsequent discussion shows, this rather simple view is nonsensical in the context of a modern economic system, however good it might be when assessing the sonic attributes of your hifi system. You don’t want positive feedback there. Especially telling I thought was the point about what does a policy maker do when the system is in a kind of equilibrium (of the steady-state growth kind)? Well, if a system is in equilibrium and it is desired that it should stay that way, then the policy maker should do nothing, other than observe.

I know that economics can be a difficult subject. But I am still amazed at how simple, yet elegant, are the finances of a monetary sovereign.

I quite agree with Bill: the entire “fiscal space” idea is a load of BS. I first started taking the mick out of it on my own blog six years ago. Unfortunately the deluded folk at the IMF and OECD are very much wedded to the idea.

Does the revolving set of persons who run plutocracies have power?

If YES, then policy (including monetary policy) is not crucial.

If NO, then policy (including monetary policy) is not saving even them.

In case of doubt read this, for example: [No one believed that Apple and Google and Facebook and all of these companies had created secret mechanisms to provide exact copies of users’ data from their servers and give it to the intelligence services, but they had. Now, we are aware that these things are not only possible, they are happening. And as a result of this, while the predation is still occurring, we can begin to resist it.] answer of Edward Snowden to ICIJ.

Look what the super rich are thinking… so far away of policy making… listen (11 minutes only) [Survival of the Richest. The wealthy are plotting to leave us behind] by Douglas Rushkoff in MEDIUM.

I accept Paul Fagan’s invitation to respond to Bill Mitchell’s critique of my column at Project Syndicate and the Guardian (“US will lack fiscal space to respond when next recession comes”) and my subsequent blogpost (“The next recession could be a bad one”).

1. As my column made clear, I don’t know when the next recession will come or what will cause it. I take as given that someday there will be another recession. Does anyone disagree with that? My mention of the high stock market among the possible triggers for a new downturn is not material.

2. To answer the question “What is a pro-cyclical policy? Does counter-cyclical policy require fiscal deficits/low interest rate in a downturn and fiscal surpluses/high interest rates in an upturn?”: Yes, it does indeed call for smaller budget balances and easier monetary policy in a downturn and stronger budget balances and tighter monetary policy in a boom.

3. I may be a “mainstream economist” and former Clinton advisor; but No, as it happens, I don’t believe that the only time for fiscal stimulus is when monetary policy hits the zero lower bound or that “at other times, [only] monetary policy should be firmly in charge of counter-stabilisation duties.” The ZLB after all was almost unheard of until the most recent decade. Regardless, I believe in fiscal stimulus when the economy is in recession (except perhaps in countries where debt is already so high that sustainability is in doubt and creditors demand a steep default premium). Leaving aside the politics, I even think the effect of fiscal policy on the economy is generally more reliable than the effect of monetary policy. I don’t know where Mr. Mitchell deduced something different from my views.

4. Evidently Mr. Mitchell believes that there is literally no limit to the extent to which a country can incur and monetize vast levels of debt relative to GDP without adverse consequence such as risking inflation and interest rates. I am sure he is familiar with economic disasters from history, including extreme example such as the current hyperinflation in Venezuela and the preceding one in Zimbabwe. Does MMT really hold that all advanced countries are somehow immune from consequences of debt, no matter how high? Just the US?

Back to basics, MMT asserts that (G-T)+(X-M)+(I-S)=0. This follows from asserting that C+S+T = GDP = C+I+G+(X-M). What is “C”? Maybe not the same on the two sides of the equation? On the left side of the GDP equation, “C” is the consumption of currency. On the right side, “C” is the consumption of assets. Two different variables. So the algebra doesn’t work. Please advise.

Dear F.Thomas Burke (at 2018/08/31 at 6:46 pm)

The C in both cases is the household expenditure on final goods and services. There is no difference. C contributes to final demand for goods and services (in the first case), and is one of the uses of national income from the second perspective.

There is no contradiction or anomaly.

best wishes

bill

Ralph, the notion of fiscal space is not in itself a load of BS, but often what is said about it is. You are right about the OECD and the IMF, though the IMF is a tad schizoid in a number of respects.

Okay. What if, out of desperation, I eat my own seed corn, reducing my capital in effect, versus eating corn from my larder or purchased at the farmers’ market? Consumption is not just a single variable?

Charles Como.

I love it LOL

Framing MMT…….a “tip of the hat” to you

Dear F.Thomas Burke (at 2018/08/31 at 9:16 am)

These aggregates are defined specifically within the National Income and Production Accounts (NIPA) and have meaning in that context.

Your example would not constitute consumption in NIPA because there is no expenditure on final goods and services at market value.

best wishes

bill

Mr. Frankel, the risk of inflation occurring from excess government spending, and/or any excess spending, is always pointed out by Bill Mitchell. Your point #4 is very uninformed as far as MMT and Bill Mitchell.

And have you looked at the Japanese economy and debt levels lately?

Mr. Frankel, while remaining critical of your point #4, I really do admire that you responded here.

Dear Alan Dunn (at 2018/08/31 at 2:46 pm)

Here is Bob at Newport on July 25, 1965 with his Fender Stratocaster.

He was playing a 1964 L-series sunburst model. The best vintage of all Stratocasters.

Here is a link to one of the songs from the concert – https://youtu.be/G8yU8wk67gY

Mike Bloomfield is playing the white telecaster.

Best wishes

bill

Bloomfield’s 63 telecaster is still in circulation – I wonder what ever happened to Dylan’s Strat ? Hopefully someone is still playing it rather than one of those cork sniffing collector types owning it.

Dear Alan Dunn (at 2018/08/31 at 4:35 pm)

Rolling Stone reported (December 6, 2013) that Bob Dylan’s 1964 Stratocaster was sold for $US965,000 by Christie’s. It “included the original leather strap and hardshell case” and first estimates were that it would sell for between $US300k to $US500k.

Rolling Stone also traced the history of the guitar since 1965:

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bob-dylans-newport-guitar-sells-for-nearly-a-million-bucks-244351/

best wishes

bill

I too appreciate Jeff Frankel’s willingness to engage with Bill M’s post.

As a self-taught MMT’er with just a little economics schooling, I must say that the MMT treatment of rising aggregate national debt over time has always fallen a bit short of coherent for me. Even if the government can keep rates very low, isn’t there a possibility that principal repayments could crowd out other needed spending? I.e., shrink fiscal space as Bill M defines it here. And is there a limit to how much the government should send out of the domestic economy to foreign investors? I guess if there is a limit, then Bill’s statement that the foreign/domestic investor mix could be shifted as desired would come into play.

Looking forward to details on MMT Univ. Thank you Bill for your outstanding contributions, which I’ve found tremendously insightful.

Thanks too for posting Bob Dylan’s Newport picture…excellent accompaniment to re-reading Chronicles as I’m doing today.

Dear Richard Genz (at 2018/09/01 at 5:59 am)

If there was a possibility of your scenario arising then the central bank can always purchase outstanding debt any time it wants. As we have seen, at various times in the past, central banks have done exactly that.

And during the GFC and in its aftermath, central bank balance sheets expanded beyond previously considered limits without inflation becoming an issue.

best wishes

bill

“2. To answer the question “What is a pro-cyclical policy? Does counter-cyclical policy require fiscal deficits/low interest rate in a downturn and fiscal surpluses/high interest rates in an upturn?”: Yes, it does indeed call for smaller budget balances and easier monetary policy in a downturn and stronger budget balances and tighter monetary policy in a boom.”

Dear Jeff,

Sincere thanks for participating from me also.

Hey, MMT regards high central bank interest rates as most likely to be stimulatory, rather than contractionary! That, I think is one of the main reasons MMT answers the question “no,” though I do not think it has not been mentioned so far in this thread!

Greg

I have a doubt…

When the government offers [interest bearing] public debt to the private sector, the private sector has a chance to invest its excess currency in that kind of almost risk-free investment.

So, currency is taken out of the private sector. So public debt expands the government’s fiscal space, doesn’t it? At least while principal/interested isn’t repaid…

If the private sector believed that investing in the public debt was risky, it would not be willing to invest as much currency at current interest rates as if public debt was risk-free. The government would not be able to expand its fiscal space so much as otherwise, or am I wrong?

If I am right, wouldn’t we be able to claim that private market’s perception of risk can indeed affect somehow government’s fiscal space?

Andre’,

I think that the Gov. still has infinite fiscal space until there is not more real resources, productive capacity, and/or available labor to increase production.

I think MMT feels that dollars in the form of a bond are not more or less inflationary than dollars in the form of a bank high interest money market account. Either can be easily converted to cash dollars to be spent. I saw a video of Stephanie Kelton where she said that the Cato Inst. put out a paper that found 56 cases of hyper-inflation in all of history, but all happened after 1900. She said that in EVERY case there was a huge element of shortages that went along with the too much cash. So I guess she is saying the the saying is “Too many dollars chasing too little stuff”; it isn’t “Way too many dollars chasing enough stuff.”

BTW — everyone can easily see that all US Gov. bonds are just IOUs and the Gov. has no need for them to be redeemed before it can issue more. So, why can’t people see that all dollars are just IOUs and that the Gov. doesn’t need dollars to be paid in as taxes before it can spend dollars?

Steve_American says

“So, why can’t people see that all dollars are just IOUs and that the Gov. doesn’t need dollars to be paid in as taxes before it can spend dollars?”

Why indeed.

But doesn’t the answer to the conundrum depend on who are “the people” who “can’t see”? Some of them can actually see just as clearly as you, but belong to the category to which Sinclair Lewis’s adage applies (the one about people who choose not to understand something when admitting that they do would cost them their salary, their standing among their fellows, or whatever). Most or all of the rest are blinded by the household-budget analogy myth which makes them unable to comprehend anything that doesn’t fit into it and furthermore haven’t acquired any understanding of what a fiat currency is: at the back of their minds lurks a vague belief that somewhere there’s an anchor in something of intrinsic value without which the whole thing would rest on nothing at all – and their minds simply can’t admit that as a possibility. “Sound finance” is just a euphemism (unacknowledged but ever-present) for “gold-backed”.

Only a generation (or two) exposed to the right teaching will make any inroads into that problem. So you’re looking at – what? – thirty years at least before light dawns.

It might help to speed-up the educative process a bit if the entire system of national accounts, shaped around the existence of the gold standard which ceased to play any part at all in the monetary system in 1971, was thrown out and replaced with one befitting a floating fiat currency regime. The terminology of the one in use sends all the wrong messages and powerfully reinforces perpetuation of a gold-standard mentality. (“Framing” again!).

Jeff

Venezuela and Zimbabwe are/were run by dysfunctional, corrupt governments, so your examples might be a tad too extreme. Could that apply to stable democracies? I doubt it!

Responding to Jeff Frankel’s comment above:

Jeff wrote, “1. My mention of the high stock market among the possible triggers for a new downturn is not material.”

It is an interesting question in its own right: the matter of whether a high CAPE (or other measure of market price) signifies a high risk of impending recession.

I agree that it is not material to the topic of “fiscal space” and government capacity to react to a downturn or recession.

On pro- and counter-cyclical policy, Jeff wrote,

“2. To answer the question “What is a pro-cyclical policy? Does counter-cyclical policy require fiscal deficits/low interest rate in a downturn and fiscal surpluses/high interest rates in an upturn?”: Yes, it does indeed call for smaller budget balances and easier monetary policy in a downturn and stronger budget balances and tighter monetary policy in a boom.”

There is a significant difference between the conditions in Bill’s question and Jeff’s answer here. Looking at the fiscal part, Bill asked if there should be fiscal deficits in downturns, surpluses in upturns. That is, he asked if Jeff thinks the balance should be net positive in booms and net negative in recessions. Jeff’s reply did not answer that: it said nothing about overall surplus/deficit, but only that the balance should be more positive in booms than in downturns (if I have understood Jeff’s use of “stronger” and “smaller” correctly).

That is an important distinction.

I was glad to see some points of agreement: Jeff wrote, “I don’t believe that the only time for fiscal stimulus is when monetary policy hits the zero lower bound,” and, “I believe in fiscal stimulus when the economy is in recession (except perhaps in countries where debt is already so high that sustainability is in doubt and creditors demand a steep default premium) … I even think the effect of fiscal policy on the economy is generally more reliable than the effect of monetary policy.”

But should fiscal stimulus be used ONLY during recessions? MMT shows that this is not necessarily the case: there can be (and often are) times when an ending of fiscal net spending (“stimulus”) would cause a recession, or at least a worsening of the lives of the country’s population.

As to the issue of doubtful sustainability and a steep premium being demanded by creditors, that is a non-issue for government spending in that government’s own currency. The government can cause the central bank to purchase government bonds at whatever premium it chooses (using base money created for the purpose by the central bank). Alternatively, there is no need to issue bonds: direct spending (with associated money creation) would work just as well.

Jeff’s fourth paragraph shows that (so far! there’s still time!) he has read next to nothing about MMT, by Bill or otherwise:

“4. Evidently Mr. Mitchell believes that there is literally no limit to the extent to which a country can incur and monetize vast levels of debt relative to GDP without adverse consequence such as risking inflation and interest rates. I am sure he is familiar with economic disasters from history, including extreme example such as the current hyperinflation in Venezuela and the preceding one in Zimbabwe.”

On the debt-to-GDP ratio: the accumulated net government spending held by the non-government sector may be in the form of “debt” (bonds or treasury bills) or in money reserves at the central bank; it makes little difference which. Those accumulated private assets are a stock, not a flow. The size of that stock is irrelevant to the government’s ability to provide a flow of spending to purchase a flow of new-made goods and ongoing services (services being inherently flow-like).

As Bill as said many times in this blog and elsewhere, inflation can be expected if net total spending in an economy (by all sectors summed) exceeds the current value of the available goods and services. Just like the private sector, the government cannot buy more than is available, and an attempt to do so will cause inflation. A government can use tax (or regulation) to reduce the purchasing ability of the private sector, thus leaving more available to be bought by government without causing inflation.

As for history, yes, Bill has written a great deal about economic history, including disasters, including the hyperinflation episodes Jeff mentions. In these cases, there was a rapid fall in the available quantity of many important goods, followed by an attempt by government to buy more than was available, so of course rapid inflation was the result.

Responding to Jeff’s final question, “Does MMT really hold that all advanced countries are somehow immune from consequences of debt, no matter how high? Just the US?”

The reasoning I have given above applies to any country working in its own currency, whether or not it is “advanced”. Of course a poor country with very limited real resources may have very little available for purchase in its own currency, but the reasoning still holds. (If a government has debt denominated in a foreign currency, things are very different.)

As an aside… even though Bill, like Jeff, holds both a doctorate and a professorship, Jeff twice refers to Bill as “Mr.” Mitchell. Bill is Australian; Jeff is USAmerican; I’m British and not so familiar with USA culture, so I don’t know: is Jeff being rude here, or just being USAmerican?

N,

He is being USAmerican.

N, very nice critique of Mr. Frankel’s response. As to your last question- I thought it bordered on rude, it got me a little angry, but what do I know. Mr. Frankel may just not care much for honorifics, in which case he should be happy to be called Mr. Frankel as well.

“As an aside… even though Bill, like Jeff, holds both a doctorate and a professorship, Jeff twice refers to Bill as “Mr.” Mitchell. Bill is Australian; Jeff is USAmerican; I’m British and not so familiar with USA culture, so I don’t know: is Jeff being rude here, or just being USAmerican?”

In professional interactions that are prof to prof, things in the U.S. are usually quickly on a first name basis, at least in most places. “Mr.” is odd perhaps for a professional context, though perhaps so are “Dr.” or “Prof.” Not so in the U.S. for a nonwork context (say at the store), where one is like any other customer, client, patient, voter, etc. There, it is more routine to use “Mr.” despite the fact that someone is a professor with a Ph.D. A good up-to-date source for writers on titles, foreign names, etc. is the internet-savvy style guide, A World Without “Whom”: The Essential Guide to Language in the Buzzfeed Age by Emma Favilla. Bloomsbury. 2017. The author is an editor for Buzzfeed.

N: Great points on fiscal space, by the way.

I am personally more bothered by signs of overvaluation, which by the way, Bill, have also included signs of elevated use of leverage, though I have not seen the margin-loan data recently. Of course, it remains hard to time the market. I see more clear signs of trouble in high-yield (junk) bond markets. Debt can of course cause problems for stocks of highly leveraged firms. I am interested to see your doubts, Bill.

Steve_American: Your comment is great; thanks for the anecdote about Stephanie. By the way, I think Venezuela has debt denominated in foreign currency. The currency-crises with hyperinflation tend to involve pegged currencies that crash, helping to cause inflation via import prices. The points about highly corrupt regimes&real resource constraints also holds.

There can indeed be absolutely no problem paying sovereign currency debt. Investors seem to understand this very well, and the ratings agencies generally give near-perfect ratings to such debt. Subjective beliefs do not move yields on sovereign-currency debt that much; capital losses have to do mostly with changes in the term premium and Keynesian liquidity preference (Keynes, General Theory Chapters 14 & 15), rather than nonpayment risk or default risk. That is why it appeared politically motivated when S&P downgraded U.S. debt slightly a few years back owing to high deficits. The only real way default can occur is by a decision not to pay a bill that can be paid at will.

Bill–one last thing: I hope you do have to delete my blog URL, as it does not appear online simply because I have entered it in the website blank on the comment form.

Thanks Bill for your ongoing contribution.

Greg

‘Cullen actually looked at 10 modern (post 1900) hyperinflations and found several common themes. First, most of the ten occurred during a civil war, with a regime change. A majority also occurred with large debt denominated in foreign currency (this included Austria, Hungary, Weimar Germany, Argentina, and Zimbabwe). I am not going to reproduce these excellent analyses, but let me just very quickly summarize key points about the Weimar and Zimbabwe hyperinflations to assure readers these were not simple cases of too much “money printing” to finance government that was “running amuck”.’

N and Jerry,

I have a moment between tasks so I would like to pose a question to each of you. Should someone who has a PHD and is a professor be given anymore respect than someone who is a just plain Mr. or Mrs.?

Someone with a PHD has spent a long time studying a discipline. Why is that more worthy of respect that the janitor who cleans up the university where the professor studied or teaches, or the garbage man that hauls away the trash from the university in all kinds of weather? Are PHD holders smarter so much more of the rest of the population that they should be given special honors? PHD holders may be a realitively small part of the population but know one should be fooled in to thinking that there are a lot lot more people out there who are capable of getting a PHD. Then on top of that considering how much damage PHD holders have done to the world pedaling in false knowledge, and considering the resources that they misused while aquiring their so called education and expertise makes me draw the conclusion that the customs of honoring PHD holders and university professors is a custom rooted in class warfare.

Dear Curt Kastens (at 2018/09/06 at 1:15 am)

It is not a matter of respect. The point is that one’s legal status changes, first when one gains a PhD – a male PhD recipient shifts legally from Mr to Dr (female from Ms/Mrs to Dr). Then in Anglo countries (excluding the US) when that person moves to the career position of holding a ‘chair’ at a university, their legal title shifts again from Dr to Professor for as long as they hold that position. Then, unless they receive the Emeritus title, they revert back to Dr upon retirement.

In European countries (particularly Northern) the legality is a little different. They move from Mr/Ms/Mrs to Dr but then become, legally, Professor Dr upon taking a job as a full professor.

So it is not about being smarter, special honors or any superiority.

It is just in law my title is Professor. I have to sign documents with that title etc.

Not that I cared for one moment that Jeffrey Frankel chose to step outside that convention for whatever reason.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

That is facsinating. Much of the western world has a legal costume that I was not even aware of. Having lived in Germany I was of course aware of the social custom of refering to people by their title.

I never liked it though because to me it seems like a form of (social) intimidation.

Dear Curt Kastens (at 2018/09/06 at 1:15 am). Hello. To answer your direct question to me- yes I saw it as a lack of respect, or at least, ignorance that any kind of simple investigation would have remedied. As were parts of the actual substance of the response that Jeff Frankel posted. Had Jeff Frankel written ‘Bill Mitchell’ rather than “Mr. Mitchell”, it would not have bothered me. It was the use of the inaccurate (and yes, less respectful title) that upset me.

But since Professor Mitchell has brushed it off as unimportant to him, I won’t complain about it anymore until next time :).