Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – February 24-25, 2018 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Estimates of cyclical fiscal balances by the IMF and other bodies are typically biased upward.

The answer is False.

The answer relies on the knowledge that the implicit estimates of potential GDP that are produced by central banks, treasuries and other bodies are too pessimistic.

The reason is that they typically use the NAIRU to compute the “full capacity” or potential level of output which is then used as a benchmark to compare actual output against. The reason? To determine whether there is a positive output gap (actual output below potential output) or a negative output gap (actual output above potential output).

These measurements are then used to decompose the actual fiscal outcome at any point in time into structural and cyclical fiscal balances. The fiscal components are adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal outcome is in deficit when computed at the ‘full employment’ or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal balance into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

As you can see, the estimation of the benchmark is thus a crucial component in the decomposition of the fiscal outcome and the interpretation we place on the fiscal policy stance.

If the benchmark (potential output) is estimated to be below what it truly is, then a sluggish economy will be closer to potential than if you used the true full employment level of output. Under these circumstances, one would conclude that the fiscal stance was more expansionary (the structural deficit was larger) than it truly was.

This is very important because the political pressures may then lead to discretionary cut backs to “reign in the structural deficit” even though it is highly possible that at that point in time, the structural component is actually in surplus and therefore constraining growth.

The mainstream methodology involved in estimating potential output almost always uses some notion of a NAIRU which itself is unobserved. The NAIRU estimates produced by various agencies (OECD, IMF etc) always inflate the true full employment unemployment rate and completely ignore underemployment, which has risen sharply over the last 20 years.

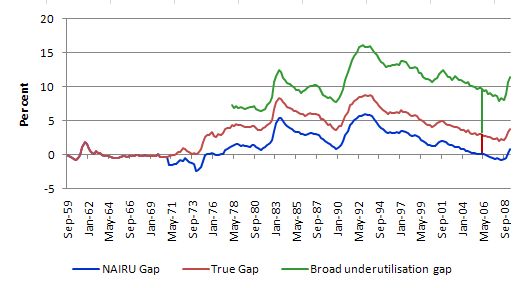

The following graph is for Australia but it broadly representative of the types of constructs we are dealing with. It plots three different measures of labour market tightness:

- The gap between the actual unemployment rate and the Australian Treasury estimate of the NAIRU (blue line), which is interpreted as estimating full employment when the gap is zero (cutting the horizontal axis).

- The gap between the actual unemployment rate and a 2 per cent full employment rate (red line), again would indicate full employment if the line cut the horizontal axis.

- The gap between the broad labour underutilisation rate published by the ABS (available HERE), which takes into account underemployment and our 2 per cent full employment rate (green line).

Some might ask why would we assume that 2 per cent unemployment rate is a true full employment level? We know that unemployment will always be non-zero because of frictions – people leaving jobs and reconnecting with other employers. This component is somewhere around 2 per cent. The other components of unemployment which economists define are seasonal, structural and demand-deficient. Seasonal unemployment is tied up with frictional and likely to be small.

The concept of structural unemployment is vexed. I actually don’t think it exists because ultimately comes down to demand-deficient. The concept is biased towards a view that only private market employment are real jobs and so if the market doesn’t want a particular skill group or does not choose to provide work in a particular geographic area then the mis-match unemployment is structural.

The problem is that often there are unemployed workers in areas where employers claim there are skills shortages. The firms will not employ these workers and offer them training opportunities within the paid work environment because they exercise discrimination. So what is actually considered structural is just a reflection of employer prejudice and an unwillingness to extend training opportunities to some cohorts of workers.

Also, the government can always generate enough demand to provide jobs to all in every area should it choose. So ultimately, any unemployment that looks like it is “structural” is in fact due to a lack of demand.

So there is no reason why any economy cannot get their unemployment rate down to 2 per cent.

Given that, the NAIRU estimates not only inflate the true full employment unemployment rate but also completely ignore the underemployment, which has risen sharply over the last 20 years.

In the June quarter 2006 the Australian NAIRU gap was zero whereas the actual unemployment rate was still 2.78 per cent above the full employment unemployment rate. The thick red vertical line depicts this distance.

However, if we considered the labour market slack in terms of the broad labour underutilisation rate published by the ABS then the gap would be considerably larger – a staggering 9.4 per cent. Thus you have to sum the red and green vertical lines shown at June 2008 for illustrative purposes.

This means that the Australian Treasury are providing advice to the Federal government claiming that in June 2008 the Australian economy was at full employment when it is highly likely that there was upwards of 9 per cent of willing labour resources being wasted. That is how bad the NAIRU period has been for policy advice.

But in relation to this question, in June 2008, the Australian Treasury would have classified all of the federal fiscal balance in that quarter as being structural given that the cycle was considered to be at the peak (what they term full employment).

However, if we define the true full employment level was at 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment, then you can see that, in fact, the Australian economy would have been operating well below the full employment level and so there would have been a significant cyclical component being reflected in the fiscal balance.

Given the federal fiscal balance in June 2008 was in surplus the Treasury would have classified this as mildly contractionary whereas in fact the Commonwealth government was running a highly contractionary fiscal position which was preventing the economy from generating a greater number of jobs.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 2:

For nations with an external surplus (such as Norway), it is sensible for the government to run fiscal surpluses and accumulate them in a sovereign fund to create more space for non-inflationary spending in the future.

The answer is False.

The public finances of a country such as Australia – which issues its own currency and floats it on foreign exchange markets are not reliant at all on the dynamics of our industrial structure. To think otherwise reveals a basis misunderstanding which is sourced in the notion that such a government has to raise revenue before it can spend.

So it is often considered that a mining boom which drives strong growth in national income and generates considerable growth in tax revenue is a boost for the government and provides them with “savings” that can be stored away and used for the future when economic growth was not strong. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows:

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending capacity is independent of taxation revenue. The non-government sector cannot pay taxes until the government has spent.

- Government spending capacity is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about “crowding out”.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

These principles apply to all sovereign, currency-issuing governments irrespective of industry structure. Industry structure is important for some things (crucially so) but not in delineating “public finance regimes”.

The mistake lies in thinking that such a government is revenue-constrained and that a booming mining sector delivers more revenue and thus gives the government more spending capacity. Nothing could be further from the truth irrespective of the rhetoric that politicians use to relate their fiscal decisions to us and/or the institutional arrangements that they have put in place which make it look as if they are raising money to re-spend it! These things are veils to disguise the true capacity of a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system.

In the midst of the nonsensical intergenerational (ageing population) debate, which is being used by conservatives all around the world as a political tool to justify moving to fiscal surpluses, the notion arises that governments will not be able to honour their liabilities to pensions, health etc unless drastic action is taken.

Hence the hype and spin moved into overdrive to tell us how the establishment of sovereign funds. The financial markets love the creation of sovereign funds because they know there will be more largesse for them to speculate with at the expense of public spending. Corporate welfare is always attractive to the top end of town while they draft reports and lobby governments to get rid of the Welfare state, by which they mean the pitiful amounts we provide to sustain at minimal levels the most disadvantaged among us.

Anyway, the claim is that the creation of these sovereign funds create the fiscal room to fund the so-called future liabilities. Clearly this is nonsense. A sovereign government’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained. So it would always be able to fund the pension liabilities, for example, when they arose without compromising its other spending ambitions.

The creation of sovereign funds basically involve the government becoming a financial asset speculator. So national governments start gambling in the World’s bourses usually at the same time as millions of their citizens do not have enough work.

The logic surrounding sovereign funds is also blurred. If one was to challenge a government which was building a sovereign fund but still had unmet social need (and perhaps persistent labour underutilisation) the conservative reaction would be that there was no fiscal room to do any more than they are doing. Yet when they create the sovereign fund the government spends in the form of purchases of financial assets.

So we have a situation where the elected national government prefers to buy financial assets instead of buying all the labour that is left idle by the private market. They prefer to hold bits of paper than putting all this labour to work to develop communities and restore our natural environment.

An understanding of modern monetary theory will tell you that all the efforts to create sovereign funds are totally unnecessary. Whether the fund gained or lost makes no fundamental difference to the underlying capacity of the national government to fund all of its future liabilities.

A sovereign government’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing. Therefore the creation of a sovereign fund in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations. In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system.

The misconception that “public saving” is required to fund future public expenditure is often rehearsed in the financial media.

First, running fiscal surpluses does not create national savings. There is no meaning that can be applied to a sovereign government “saving its own currency”. It is one of those whacko mainstream macroeconomics ideas that appear to be intuitive but have no application to a fiat currency system.

In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we note that governments spend by crediting bank accounts. There is no revenue constraint. Government cheques don’t bounce! Additionally, taxation consists of debiting an account at an RBA member bank. The funds debited are “accounted for” but don’t actually “go anywhere” and “accumulate”.

The concept of pre-funding future liabilities does apply to fixed exchange rate regimes, as sufficient reserves must be held to facilitate guaranteed conversion features of the currency. It also applies to non-government users of a currency. Their ability to spend is a function of their revenues and reserves of that currency.

So at the heart of all this nonsense is the false analogy neo-liberals draw between private household budgets and the government fiscal state. Households, the users of the currency, must finance their spending prior to the fact. However, government, as the issuer of the currency, must spend first (credit private bank accounts) before it can subsequently tax (debit private accounts). Government spending is the source of the funds the private sector requires to pay its taxes and to net save and is not inherently revenue constrained.

You might have thought the answer was maybe because it would depend on whether the economy was already at full employment and what the desired saving plans of the private domestic sector was. In the absence of the statement about creating more fiscal space in the future, maybe would have been the best answer.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A mining boom will not reduce the need for public deficits

- The Futures Fund scandal

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

Question 3:

We would never observe a state where a nation was running an external deficit (trade and income flows), a fiscal surplus and the private domestic sector was spending less than it was generating.

The answer is True.

This question relies on your understanding of the sectoral balance relationships.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

You can see that if the external balance is in deficit and the fiscal balance is in surplus, then the private domestic sector must be spending more than it is earning (S < I), that is in deficit. Take an example - from Expression (5) (S - I) = (G - T) + CAD Let the fiscal surplus (G < T) be 2 per cent of GDP and the external deficit be 3 per cent of GDP. Then (S - I) = -2 + (-2) = -4 That is S < I. The private domestic sector is spending more than it is earning and running a deficit. That has to be the case as a matter of accounting. That is enough for today! (c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I wish we could find different language and framing for “tax revenue.” and use something else.

“Revenue” is good. Before something comes back, it has to leave.

“Estimates of cyclical fiscal balances by the IMF and other bodies are typically biased upward.

The answer is False.”

So – let me check if I’ve got this right – in truth, “estimates of cyclical balances by the IMF and other bodies are typically biased DOWNWARD.”

So the IMF etc are usually underestimating the cyclical component of the deficit because their estimate of what constitutes “full employment” is too high – i.e. 5% rather than 2%.

Somehow I got confused because I think it is right to say that the IMF etc assume structural deficits to be more expansionary than they really are due to the same causation – overestimating full employment rate. I should have been more careful when I saw the word “cyclical”.

I got the Norway question right – but I do remember some mention of one possible benefit of a sovereign wealth fund – is that it could facilitate the purchase of imports in foreign currency at a later date – something like that….?

As always very tricky questions that make sure you stay humble. One of the highlights of my intellectual week as an autodidact economist however!

Question 1:

Does anyone ever ask how a “negative output gap” is even possible for a country; how can it ever be producing more than it is capable of producing?

“To determine whether there is a positive output gap (actual output below potential output) or a negative output gap (actual output above potential output).”

Are these around the wrong way?

The discussion of Q2 focuses on the futility of a currency issuer accumulating the currency that they issue. However, sovereign funds often accumulate foreign assets, that they can spend abroad without generating local income. How does that change the inflation argument, if at all?

I did not understand question 1, to be honest, so I’m grateful for the detailed explanation.

One thing I’m still not clear about, even after reasonably extensive studying of Bill’s articles, some of his books, and some of those of other MMT experts, is to what extent a country can survive with a permanent trade deficit.

Yes, we know that the USA can and does survive, but the USD is surely a special case, and of course, the USA used to be in trade surplus (until around the early 1970s I think?).

A case in point might be Venezuela, which is/was so dependent on its oil, and for whom the world seems to have collapsed along with the price of oil collapsing. (Has Bill written explicitly about Venezuela, I wonder? – I will have a proper search later, but I don’t think there is an article that deals exclusively with it). I’m probably just a conspiracy theorist, but I’ve always thought that the fall in the oil price was deliberately engineered to attack countres like Venezuela and Russsia, who do not toe the US line (or is that too obvious even to need saying?)).

@ Mike Ellwood,

A country can survive indefinitely with a trade deficit. Indeed, it means that the country is able to consume more than it produces. If some countries want to consume less than they produce indefinitely, then other countries can indefinitely consume more than they produce.

Dear JT,

Is it reahlistic to figure that the people of any country would want to consume less than they produce for any long length of time? Predominately Christian countries? Predominately Sufi Muslim countries?

Curt