I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Why doesn’t this attract headlines?

Why doesn’t this article get headlines in the newspapers? Today I read a recent article – Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves? – from two researchers at the New York branch of the Federal Reserve Bank. It is obvious that the authors understand much more about the modern monetary system than most of the journalists, economists and politicians who make so-called informed commentary about such matters. Three messages emerge: (a) bank reserves play an important role in the conduct of interest rate policy and budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates; (b) the money multiplier conception of economics is inapplicable to a modern monetary system; and (c) the current build-up of bank reserves will not be inflationary. I thought that it would be nice for you to read this stuff from someone other than billy blog (and my fellow modern money travellers!).

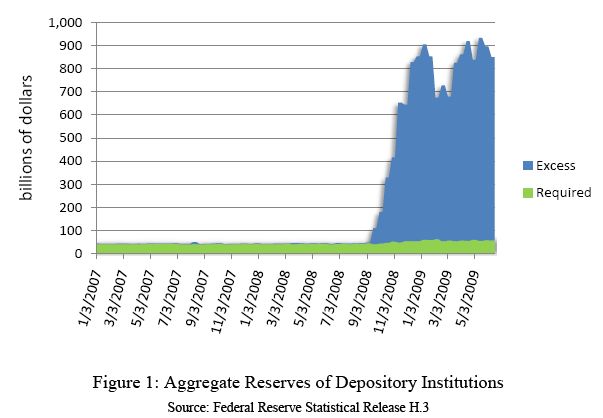

To condition our minds, the following graph, taken from the Fed Report, shows the huge growth in the quantity of reserves held by American banks since September 2008. The authors note that:

Prior to the onset of the financial crisis, required reserves were about $40 billion and excess reserves were roughly $1.5 billion. Excess reserves spiked to around $9 billion in August 2007, but then quickly returned to pre-crisis levels and remained there until the middle of September 2008. Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, however, total reserves began to grow rapidly, climbing above $900 billion by January 2009. As the figure shows, almost all of the increase was in excess reserves. While required reserves rose from $44 billion to $60 billion over this period, this change was dwarfed by the large and unprecedented

rise in excess reserves.

The questions of interest are: (a) “Why are banks holding so many excess reserves?”; and (b) What does this data “tell us about current economic conditions and about bank lending behavior?”

The Fed Report defines bank reserves (and this holds for Australia as well as any country) as:

… funds held by depository institutions that can be used to meet the institution’s legal reserve requirement. These funds are held either as balances on deposit at the Federal Reserve or as cash in the bank’s vault or ATMs. Reserves that are applied toward an institution’s legal requirement are called required, while any additional reserves are called excess.

The Report notes that these excess reserves are considered problematic by so-called informed commentators who believe their existence means banks prefer to hoard cash rather than lend – hoarding is then the reason for the credit crunch. For example, one of the top mainstream macroeconomics textbook writers Gregory Mankiw actually wrote in the New York Times on April 19, 2009 that something had to be done to stop banks “cash hoarding” and forcing them to lend. Other well-known mainstream monetary commentators have been recommending taxes on reserves and/or caps to stop the banks “hoarding”.

The authors appear to share my perspective – that these major players in the macroeconomics debate do not have a clue as to how the monetary system actually operates (or lie about it) and draw their commentary from standard mainstream macroeconomics textbooks which develop theory that is virtually about another planet – gold standard dynamics and constraints and money multiplier fractional reserve banking models. Clearly they don’t say it in this way but that is the message of their report.

You will also understand from this that our students across the world are being fed total nonsense in their macroeconomics courses and it is no wonder the myths are perpetuated when the leading professors are themselves unable to comprehend how the system operates.

Let me state again for the millionth time – banks can lend any time they want and do not need prior reserve balances to do so. Loans creates deposits which are then backed by reserves subsequently. The only reason that the banks are not lending at present is that they have tightened their conception of a credit-worthy customer because they have become risk-averse in the face of the crisis. The level of reserves is irrelevant to this “stand-off”.

The Fed Report tackles the ignorance of mainstream macroeconomists head on. It motivates the paper in this way:

The total level of reserves in the banking system is determined almost entirely by the actions of the central bank and is not affected by private banks’ lending decisions. The liquidity facilities introduced by the Federal Reserve in response to the crisis have created a large quantity of reserves. While changes in bank lending behavior may lead to small changes in the level of required reserves, the vast majority of the newly-created reserves will end up being held as excess reserves almost no matter how banks react. In other words, the quantity of excess reserves depicted in Figure 1 reflects the size of the Federal Reserve’s policy initiatives, but says little or nothing about their effects on bank lending or on the economy more broadly.

This conclusion may seem strange, at first glance, to readers familiar with textbook presentations of the money multiplier. After presenting our examples, we discuss the traditional view of the money multiplier and why it does not apply in the current environment … We also argue that a large increase in the quantity of reserves in the banking system need not be inflationary, since the central bank can adjust short-term interest rates independently of the level of reserves.

The Report begins by providing a simple accounting example to show that central bank actions determine the level of reserves in the banking system. I won’t repeat that example here as it is basic accounting. Some readers might find it interesting though to concentrate ones mind on the framework being discussed.

The authors then consider the impact of excess reserves on the interest rate. In the US, bank reserves have historically earned zero interest. In Australia, the RBA pays 25 basis points below its target interest rate on overnight reserves.

Using an example with two commercial banks interacting with the central bank (The Fed), the Report shows that:

If Bank A earns no interest on the reserves it is holding … it will seek to lend out its excess reserves or use them to buy other short term assets. These activities will, in turn, decrease the short-term market interest rate. Recall, however, that we assumed that the central bank has not changed its target interest rate. The central bank thus has two distinct and potentially conflicting policy objectives in our example.

The appropriate short-term interest rate is determined by macroeconomic conditions, while the appropriate lending policy is determined by the size of the problem in the interbank market. If the amount of central bank lending is relatively small, this conflict can be resolved using open market operations. In particular, the central bank could sterilize the effects of its lending by selling bonds from its portfolio to remove the excess reserves.

So you see that when there are excess reserves and the central bank offers no return on them to the banks, the latter drive down the short-term money market rate (interbank rate) as they try to rid themselves of the excess reserves. This brings the reality in the interbank market into conflict with the central bank’s monetary policy target rate (assumed to be unchanged). In other words, the central bank loses control over its monetary policy position.

The only way they can regain control is to prevent this interbank competition from occurring and they do that through “open market operations” – that is, selling government bonds “from its portfolio to remove the excess reserves”. Fundamental operation. Debt issuance to remove excess reserves rather than to finance net government spending.

Further, so-called horizontal transactions between non-government entities net to zero. The Fed Report says:

… it is important to keep in mind that total reserves in the banking system are determined almost entirely by the central bank’s actions. An individual bank can reduce its reserves by lending them out or using them to purchase other assets, but these actions do not change the total level of reserves in the banking system.

If you read my blog – Money multiplier myths – you will find more about the reasoning here. It is a crucial point. Only vertical transactions between the government and non-government sector can add or drain reserves. All the leveraging transactions between non-government entities only redistributes reserves. If there are excess reserves in the system, only an intervention from the government can reduce them – so a bond sale will do that.

Note that budget deficits will result each day in excess reserves. If the central bank does not drain these reserves then interest rates will fall. Clearly, budget deficits in their own right put downward pressure on interest rates. The debt issuance then allows the central bank to curtail this market pressure and maintain higher rates according to its current monetary policy stance.

But the higher rates have nothing to do with the net spending – or having to “finance” it – as you will read to your detriment in the standard macroeconomics textbooks under “financial crowding out”. The higher rates are just a statement of the central bank’s intended monetary policy stance and it can change that whenever it wants to.

Now how does paying an interest rate on the excess reserves change things? The bond sales in the previous case choked off the incentive that the banks who held excess reserves had to lend the reserves out. This curtails the downward pressure on the interest rate. If the central bank doesn’t want to sell treasuries (bonds) then it has another alternative.

The central bank can:

… eliminate the tension between its conflicting policy objectives … [by paying] … interest on reserves. When banks earn interest on their reserves, they have no incentive to lend at interest rates lower than the rate paid by the central bank. The central bank can, therefore, adjust the interest rate it pays on reserves to steer the market interest rate toward its target level.

Simple as that! There are no opportunity costs to banks in holding reserves and the central bank’s target interest rate becomes independent of the level of reserves in the banking system.

What about the money multiplier?

The authors note that:

The idea that banks will hold a large quantity of excess reserves conflicts with the traditional view of the money multiplier. According to this view, an increase in bank reserves should be “multiplied” into a much larger increase in the broad money supply as banks expand their deposits and lending activities. The expansion of deposits, in turn, should raise reserve requirements until there are little or no excess reserves in the banking system. This process has clearly not occurred following the increase in reserves depicted in Figure 1.

I recall one of my early teachers (an unnamed mainstream professor at a leading University) made the comment once in a lecture that given the “empirical facts or data” didn’t accord with neoclassical economic theory then we should conclude that the “facts were wrong”. He was serious. It was not a flippant comment. These characters are welded to their textbook theories and just deny the existence of any facts that are contrary to their models.

You can also see why a curious young mind not intent on climbing the corporate world would start looking to alternative theories to find some sense of understanding. My journey into modern monetary theory started way back then ….!

The money multiplier is one of those welded on concepts that the orthodox economists refuse to relinquish. They teach it day in-day out in universities – largely because the theory is taught via some algebra and some ratios that make the lecturers look scientific in the eyes of their students. The models seem to satisfy some childlike (anal) desires for formality and rigour (as they not me conceive it) . Who can tell why otherwise smart characters continue year after year to teach in great detail a model that has no bearing on the way the monetary system operates?

Anyway, the Fed Report seeks to explain why the money multiplier doesn’t help up understand the current situation. If you read the article you will soon realise that the authors themselves are struggling to jettison the myth. They say that:

The textbook presentation of the money multiplier assumes that banks do not earn interest on their reserves. As described above, a bank holding excess reserves in such an environment will seek to lend out those reserves at any positive interest rate, and this additional lending will decrease the short-term interest rate …

This multiplier process continues until one of two things happens. It could continue until there are no more excess reserves, that is, until the increase in lending and deposits has raised required reserves all the way up to the level of total reserves. In this case, the money multiplier is fully operational. However, the process will stop before this happens if the short-term interest rate reaches zero. When the market interest rate is zero, banks no longer face an opportunity cost of holding reserves and, hence, no longer have an incentive to lend out their excess reserves. At this point, the multiplier process halts.

Well not really. The real issue is that the money multiplier theory conceives of banks as waiting for deposits and when they come along they are then able to lend. That is deposits provide the reserves which then promote lending. That is not the way the system operates. Loans create deposits and reserves are added later.

The reason why banks try to lend out excess reserves in the interbank market is because they are assets that are earning no return. A somewhat different conception and motivation. And clearly, once the overnight rate is zero, the banks have no further profit opportunities to exploit. The other point is that they realise that this interbank activity does not rid the system of the excess reserves – it just shuffles them around as the competition is driving the interest rate down and wresting control of monetary policy target from the central bank.

But the Fed Report then says:

When reserves earn interest, the multiplier process described above stops sooner. Instead of continuing to the point where the market interest rate is zero, the process will now stop when the market interest rate reaches the rate paid by the central bank on reserves. If the central bank pays interest on reserves at its target interest rate, as we assumed in our example above, the money multiplier completely disappears. In this case, banks never face an opportunity cost of holding reserves and, therefore, the multiplier process described above does not even start.

So they are calling the interbank competition process the multiplier process which is stretching the conception in my view. But semantics aside, the process they describe is correct. Any support rate below the target monetary policy rate will create a corridor in which the interbank competition will move the overnight rate. Once the overnight rate is at the support rate (which may be zero), then the interbank competition stops because there are no further profit opportunities for any single bank.

We deal with this “corridor” issue in detail in my latest book – Full employment abandoned: shifting sands and policy failures.

Is the large quantity of reserves inflationary?

You will recall often that commentators consider the modern monetary approach to macroeconomics to be a recipe for hyperinflation. Even the debates about whether The Greens were neo-liberal or not centred, finally, on this claim.

The Fed Report addresses the issue head on and cites leading US mainstream macroeconomists (Feldstein, Meltzer etc) who claim that the reserves will underpin “faster money growth” and inflation.

The authors note (with some confusion I might add – that is, they stumble on the correct answer) – that:

When the economy begins to recover, firms will have more profitable opportunities to invest, increasing their demands for bank loans. Consequently, banks will be presented with more lending opportunities that are profitable at the current level of interest rates. As banks lend more, new deposits will be created and the general level of economic activity will increase. Left unchecked, this growth in lending and economic activity may generate inflationary pressures.

… where no interest is paid on reserves, the central bank must remove nearly all of the excess reserves from the banking system in order to arrest this process … By raising the interest rate paid on reserves, the central bank can increase market interest rates and slow the growth of bank lending and economic activity without changing the quantity of reserves. In other words, paying interest on reserves allows the central bank to follow a path for short-term interest rates that is independent of the level of reserves. By choosing this path appropriately, the central bank can guard against inflationary pressures even if financial conditions lead it to maintain a high level of excess reserves.

This is a very important piece of text and it is crucial to understand the operations that are being described. The authors are saying that interest rate levels affect aggregate demand (we can argue about that but at this point that is not the issue). Assuming the central bank thinks that – then it seeks to adjust monetary policy (overnight interest rates) to reflect the state of demand in the economy relative to real capacity left to respond to that nominal demand (spending) growth). Pretty conventional really.

If they think there are inflationary pressures they seek to hold interest rates higher than otherwise and vice versa. The only way they can do that is to ensure that there are no excess reserves in the system at any point in time which will provoke interbank competition and drive the interest rate drown to zero (Japan case!). In that situation, the central bank would lose control of its target interest rate and monetary policy would be too loose for their liking.

So what do they do? They have to “remove … all of these excess reserves from the banking system”. How? By issuing government debt securities which provide the banks with a competitive interest-bearing asset instead of the non-interest bearing reserves. So government debt issuance is about interest-rate maintenance and has nothing to do with financing treasury fiscal positions. That is what the authors are saying in this paper.

But the central bank can avoid the necessity of draining the excess reserves quite simply by paying the banks an interest rate on the reserves. This is equivalent in operational terms to issuing debt but in this case it separates the central bank’s “path for short-term interest rates” from the level of reserves. They become independent of each other.

In other words, the banks have no incentive to loan out the reserves in pursuit of competitive returns on non-performing assets. This means the central bank can hold its target interest rate (which is targetting an anti-inflationary position) and according to that logic, stifle any inflation pressures arising from excessive aggregate demand.

So do all you hyperinflators out there get that? It should stop you raising this issue once and for all and also disabuse you all of the notion that debt issuance has something to do with financing fiscal policy positions. The Fed Reserve authors are not me remember!

Interestingly, the authors see advantages in retaining high reserve levels even in normal times. They say:

A central bank may choose to maintain a high level of reserve balances in normal times because doing so offers some important advantages, particularly regarding the operation of the payments system. For example, when banks hold more reserves they tend to rely less on daylight credit from the central bank for payments purposes. They also tend to send payments earlier in the day, on average, which reduces the likelihood of a significant operational disruption or of gridlock in the payments system. To capture these benefits, a central bank may choose to create a high level of reserves as a part of its normal operations, again using the interest rate it pays on reserves to influence market interest rates. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has used this type of framework since 2006.8

Again, this should choke off a few of those hyperinflators as long as they have the grey matter left to actually understand how the system operates in practice rather than how they (erroneously) conceive of it operating – all the time being conditioned by textbooks that bear no relation to the real monetary system they purport to describe and explain.

Conclusion

So how about all that? Imagine the headlines:

1. Budget deficits driving down interest rates!

2. Debt build-up reflects central bank desire to hold target interest rate at current level!

3. Zero debt build-up if RBA pays competitive rates on excess reserves!

And the rest of it.

Of-course, none of you will be deceived. The payment of interest on the excess reserves is equivalent to paying interest on a government bond. It is performed in the same way (typing numbers into bank accounts), is not revenue-constrained, and provides a competitive return on reserves (held as reserves or IOUs).

Neither, monetary policy operation (debt issuance or interest-payments on reserves) presents the slightest problem for government solvency or its capacity to net spend to underwrite full employment.

It should also be clear that the macroeconomics that you will learn from a mainstream textbook has nothing sensible to say about the economy. Further, all students should start undermining their macroeconomics classes by demanding to know why their lecturers are persisting in lying to them.

Students might usefully start petitions, hold rallies and otherwise bring these characters to account.

Dear Bill,

You have a lot more faith in economics students than I do. In the three years I tutored and lectured I probably came across three students who I would rate as economists. All three of them were female and none of them went on to make their livings as economists.

And that for me is the problem. The good ones that understand how things operate and could genuinely make a difference don’t want to be a part of it, and the trained monkeys who have been programmed to think the orthodox theory is correct usually head to Canberra to perpetuate the lies on behalf of government and big business.

Unfortunately, I think the only students who would start undermining their macroeconomics classes by demanding to know why their lecturers are persisting in lying to them would be the deciples of the orthodox school rather than modern money advocates.

Cheers, Alan

It was a nice article by the Fed guys. Chicago Fed’s paper “Modern Money Mechanics” is also a good one and it says Loans create deposits and banks are not constrained by reserves. However it talks of contraction of the money supply while targeting the overnight rate and as we have learned in this blog, these two cannot be achieved simultaneously.

However, the Fed article seems to suggest that paying interest on reserves decreases lending. Paying interest on reserves has only one purpose – preventing Fed Funds rate from hitting zero. An example can illustrate this – let us say that the overnight rate is 3% and the reserve requirement is 10%. A $100,000 in excess of reserves can earn about $3000 per year as interest from the Fed. However, $100,000 in excess gives the potential of a $1,000,000 in loans and hence lots in profits. Clearly the question is whether the bank likes the customer or not and not how much the interest paid on Fed Funds is. If a bank likes a customer, it will not really compare it to holding. The interest on the excess reserves is paid to the bank not to prevent loans but to prevent it from lending it to other banks below a level.

Dear Ramaman

They do think that the return on reserves will constrain lending between banks. They also consider it will allow the central bank to maintain a higher than other target (policy) interest rate independent of the reserves that are in the system and keep a lid on overall loan creation. In that sense, it is the higher rates that constrain aggregate demand and hence reduce the number of prospective borrowers. It relies on the assumption that aggregate demand is fairly sensitive to interest rate movements which I don’t think is true within usual interest rate limits. So while I don’t agree with them on that – it is clear the monetary operations they articulate are totally consistent with modern monetary theory and inconsistent with the standard textbook monetary economics.

best wishes

bill

Yes Bill, understood their sense of reasoning.

Also understand that there is no proof of even a reasonable elasticity of investments on interest rates. Its really low. Only when interest rates jump to very high levels, can one see some dependence.

Neither is there any proof of an effect of the rates on inflation. There are some papers on the internet (a lot written by Central bankers) which just take the correlation between interest rates and inflation and conclude that the monetary policy has a big effect. That is really a bad way to do the analysis. However, the question to ask is if a change of rates has really brought down the price levels or achieved any stability. I think your book talks of this question and there doesn’t seem to be any effect is what you conclude.

Bill,

Can lower interest rates lead to increased aggregate demand through the asset price channel?

Dear Bill

Perhaps the most annoying thing of all is that those of us like you, me, and many of our friends that have had this right for years–and have blogged about it numerous times, even lately as you and I have done–don’t get cited when some well-placed economists finally do get it right (or more than half right, as these folks obviously get a few things wrong, as you noted).

Best,

Scott

Bill, Scott:

They may have had this right longer than you suspect.

In early 2007, I stumbled across the following description in the ‘reserve requirements’ section of the New York Fed web site:

“The Federal Reserve operates in a way that permits banks to acquire the reserves they need to meet their requirements from the money market, so long as they are willing to pay the prevailing price (the federal funds rate) for borrowed reserves. Consequently, reserve requirements currently play a relatively limited role in money creation in the United States.”

The reason I haven’t included a link is that it is no longer there.

The reason it is no longer there is that they are reworking the reserve requirement section, updating it – presumably to incorporate how the world has changed since they started paying interest on reserves and running a huge system excess.

(Unless they’ve already updated the section; I haven’t checked lately)

Dear JKH

Thanks for that. There is no doubt they have written about the central bank’s responsibilities to ensure that reserves were adequate in the system. But I haven’t seen them write about the actual operating factors whereby debt is issued to allow them to maintain control of their interest rate target.

Unlike Scott, I actually don’t care who says it as long as the message gets out and policy makers start targetting the right things (low unemployment) and stop targetting the wrong things (particular budget outcomes). It is clearly good to be acknowledged for one’s work but that is a trifling matter compared to what is at stake.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

I agree that recognition isn’t the point, particularly compared to what’s at stake, as you said. My point has more to do with academic integrity . . . these aren’t original ideas, though they don’t cite any of the many, many people who have said all this before and they will very likely get some credit for their work here as time goes on. Their paper was an academic piece, and academic standards of attribution would seem to apply.

Dear JKH

Yes, the NY Fed has gotten operations right many times before . . . they get it right every year in their annual report on open market operations, in fact.

Best to you both,

Scott

Dear Scott

I agree with your position on that.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

As I see it (rather simplistically perhaps: taking a mathematical rather than an economic perspective), while it is easy enough to define the money multiplier as the ratio of money supply (however you choose to measure it) and the monetary base, if it is to be a useful concept in the way it is generally taught, one would want it to have the following two features:

1. it is greater than one (not much of a “multiplier” otherwise)

2. it is (reasonably) constant over time

If you look at the data (courtesy of the excellent St Louis Fed “FRED” database), at the moment neither would appear to be the case!

So, there’s a heuristic counterpart to your monetary theory functional arguments against the usefulness of the concept.

Sean.

Thank you, Bill, for your wonderfully enlightening blog. As a layman with only a very peripheral background in economics, I find this all quite fascinating. If I’ve been following you correctly, government debt issuance is necessary only as a means of withdrawing high powered money from the system so that the central bank can maintain control of the interest rate on loanable bank reserves.

If this is the case, I’m wondering if, with payment of interest on bank reserves, there is any need for government debt at all? Presumably, reserve injections need not be associated with a plunging funds rate in this case, obviating the need for mopping up reserves via debt issuance, provided there is some tolerance for the presence of excess reserves in the system. I must be missing something? I guess this approach would see significant build up of bank reserves in the system, with a corresponding decrement in government debt, and would lead to a shift in interest transfers to the banking system specifically, rather than to government debt holders in general? It seems that interest payment on reserves should, or could, expose the myth that the government needs to borrow in order to fund itself?

Apologies for butting in with what may be a silly question.

Dear JKH,

Its there – http://www2.newyorkfed.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed45.html

Bill,

This is outstanding stuff. I have only one minor point. The Fed, in conducting open market operations where they have to sell bonds to mop up reserves, haven’t and don’t cause bonds to be issued in order to have bonds to sell. They already have the bonds in their own Treasury bond portfolio which they have accumulated over time. My understanding is that the bonds actually used in open market operations always come from the Fed’s bond portfolio, which has consituted a significant part of their balance sheet for a long, long time. I realize by sheer logic that debt is issued by the Treasury as an interest bearing deposit for investors and as an interest rate control mechanism to be utilized by the Fed. I imagine the Fed just purchases in the open market in order to acquire and build the portfolio, but I don’t think they buy directly from the Treasury at issuence time.

Obviously if one views the Fed and the Treasury as one consolidated entity, which one should do, it makes no difference whatsoever.

All the best

Dear Barton

Exactly right. I abstracted from where the bonds came from (new issue or existing stock) because for operational analysis I always think of the central bank and the treasury as the government.

best wishes

bill

Dear Paradigm Shift (nothing obvious about that name, eh?)

You are not missing anything. The payment of interest on reserves obviates the need to conduct open market operations to manage the level of bank reserves such that the central bank can maintain control of its interest rate target. There is also a case to be made for higher levels of reserves in terms of the efficiency of the payments system.

best wishes

bill

Ramanan,

Thanks very much. Very strange. My original bookmark wouldn’t work. I’d assumed they were working on an update, and could have sworn I saw a message to that effect at one point. But it’s exactly the same. Thx again.

Bill,

The question of unnecessarity of bonds brings one to the question – are banks getting a free lunch by getting the government bonds ? The yield of, say, a ten year treasury is on an average higher than the overnight rates over the ten year period (in an expected sense). In other words, do banks earn a term premium for free ?

Dear Ramanan,

I can in no way replace Bill’s commentary, but drawing from over 25 years experience in the bond market, I am led to say that yes, right now the banks are getting a sort of free ride in the sense that the yield spread between Fed Funds and the 10 year Treasury is in excess of 320 basis points. Thus to the degree that banks are actively going further out the yield curve and buying 5, 7 and 10 year Treasuries they are earning a great a great yield spread over their cost of funds. Of course I don’t have statistics to hand, so I couldn’t speculate on the size or volume of bank purchases of Treasury bonds further out than the shorter part of the curve. Naturally, the further out the curve they go, the greater the principal risk they take due to the increasing sensitivity of the bond’s price to a change in interest rates (a measure known as duration), but certainly for a portion of their liquid assets they are buying Treasury bonds and it’s been a great ride for them to date, though not exactly a totally free ride. And of course this also puts paid to the deficit hysteria question of “where are the funds going to come from to buy all those bonds that the government supposedly HAS to sell to “fund” its burgeoning deficit”? Why, lots and lots of those dangerous excess reserves are finding a very nice home in Treasury bonds!

The only other point I would make is that the Government, by issuing bonds, is not catering only to the banks. Investors of all kinds, both institutional and individual, are being given the opportunity to purchase a government guaranteed interest bearing instrument, which is HIGHLY useful to investors and to the financial markets and maybe even to society in general. And lest we forget, the sale of bonds by the Treasury adds to private wealth.

Best Regards

depist

Dear Bill

Great stuff as always. Wonder if you could spare the time to read this blog entry

http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/finance/edmundconway/100000349/housing-still-being-strangled-by-the-credit-crunch/

which seems to bang the same drum about banks ‘hoarding’ cash. As you can see from the graph featured in the blog entry the excess reserves of UK banks has spiked in a pattern similar to the US example, which reflects the extraordinary policy measures of the central bank rather than bank lending practices.

The blogger also uses the example of a UK building society which is holding an extraordinary level of reserves at the central bank compared to normal times, 1 billion pounds sterling vs 150 million before the financial crisis.

now the authors of the Fed report highlight that the overall excess reserves that banks are holding at the central bank does NOT indicate particular lending patterns, but that individual banks with excess reserves can lend those excess reserves if they choose to.

Can i ask, and i’ve probably missed the crucial point, but under what circumstances do you think banks and the building society in this example will deplete these unusually high reserves by lending them out. Is it as simple as that once they believe they have the required demand and number of borrowers for these excess that they’ll choose to lend these excesses. Or does the excesses the skipton holds at the bank of england NOT reflect how much the building society is able in theory to lend to borrowers.

Dear Tricky,

“Lending the reserves out” does not convey a very accurate description of what happens or what will happen when lending picks up.

Let us assume that a US bank has $1b in reserves (and most of it is excess). Let us say, that a customer visits the bank for a loan of $1m and the bank likes him/her and gives the loan. Most people would normally picture this as the bank “taking out” $1m from the Fed and granting it to the customer. However, this is not the case. The reserves of that bank at the Fed is still $1b. Not $1b minus $1m. Exactly $1b.

Loan growth will move upward when the aggregate demand picks up.

Ramanan: in your example, you are making one assumption that may not be valid, namely that the customer borrowing the money either keeps it in an account with the bank or gives the money to another party who also banks at the same bank (let’s call it bank A). However, it is just as likely that the customer borrows the $1m and, for example, uses the money to buy a house (or a factory or milk or cheese or whatever) and so pays the money to a vendor who banks elsewhere (bank B). In this example, the reserves of bank A would be reduced and the reserves of bank B would increase. Of course, if bank A does not actually have excess reserves, it might borrow the money back from bank B.

The important point, though, is that this lending does not increase the aggregate reserves, although it may move reserves from one bank to another. As Bill has often noted, the aggregate amount of reserves can only be changed by means of transactions between the government and private sectors. Purely private sector transactions simply shuffle the balances between different private sector entities.

Thanks Barton for your reply.

Sean,

Yes, the assumption is not valid. I should have written it at the level of the whole banking sector not an individual as you pointed out.