I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Britain doesn’t appear to be collapsing as a result of Brexit

Do you remember back to May 2016, when the British Treasury, which is clearly full of mainstream macroeconomists who have little understanding of how the system actually operates released their ‘Brexit’ predictions? The ‘study’ (putting the best spin possible on what was a tawdry piece of propaganda) – HM Treasury analysis: the immediate economic impact of leaving the EU – was strategically released to have maximum impact on the vote, which would come just a month later. Fortunately, for Britain and its people, the attempt to provide misinformation failed. As time passes, while the British government and the EU dilly-dally about the ‘divorce’ details, we are getting a better picture of what is happening post-Brexit as the ‘market’ sorts what it can sort out. Much has been said about the destructive shifts in trade that will follow Brexit. But these scaremongers fail to grasp that Britain has been moving away from trade with the EU for some years now and that process will continue into the future. I come from a nation that was dealt a major trading shock at the other end of Britain’s ill-fated dalliance with Europe. It also made alternative plans and prospered as a result. The outcomes of Brexit will be in the hands of the domestic policies that follow. Stick to neoliberalism and there will be a disaster. But the opportunity is there for British Labour to recast itself and seize the scope for better public infrastructure, better services and stronger domestic demand. Then the nation will see why leaving the corporatist, austerity-biased failure that the EU has become was a stroke of genius.

The only good thing about the Treasury Report was that it was “Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum” but even then it was a waste of real resources.

The aim of the Report was to quantify “the impact of that adjustment over the immediate period of two years following a vote to leave”. It was not about medium- or long-term impacts. It was about then and now.

The findings were based on mainstream ‘economic’ and ‘econometric’ models’ that continually fail to deliver plausible results. But that has never stopped the ideologues who hide behind them as if they constitute an intellectual authority.

The Treasury claimed to support analysis by the Bank of England and the IMF, which also predicted “a recession following a vote to leave”.

Madame Lagarde was quoted as saying that “there’s a range of possible scenarios … which could possibly include a technical recession”, which, of course, is not the same thing as a certain recession. But these characters are always using words like ‘could’ or ‘might’ to put a negative spin on some future event that they have no clue about.

The Report predictions of the “immediate economic impact” are summarised by the following table, which ‘models’ two scenarios – a Shock and a Severe Shock:

So “In the severe shock scenario, the analysis shows that after two years the level of GDP would be 6% lower, the number of people unemployed would rise by around 800,000, sterling would depreciate by 15% and CPI inflation would increase by 2.7 percentage points after a year.”

I laughed at the time when I read the footnote “Unemployment level rounded to the nearest 10,000” – as if that level of accuracy was present.

The predictions sounded pretty dire really. Well with around 6 months to go before the two years is up, the British economy better fall off the cliff fairly quickly because it has largely been heading in the opposite direction to these predictions.

The Remainers who read my blog and send me E-mails claimed my early assessments of what had been happening were premature that all would be revealed in the second half of 2017 and beyond.

I suppose they will just keep pushing this time horizon out until there is actually another cyclical downturn and then gloat ‘we told you so’ – Brexit caused this.

When Britain entered the Common Market

Many readers will be unaware that when Britain entered the Common Market in 1973, Australian trade patterns were severely shocked (along with other Commonwealth nations).

The decision by Britain to enter the EEC (“accession to the EEC”), which became operational on January 1, 1973, was a shock to Australia and many of the generation who had fought in either World Wars in the 1900s were deeply offended.

This reflection by a former Australian politician (now Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom) – Australia was wounded when Britain joined the EU. Now we can make things right – as partners – sums up the issue:

My father’s generation was deeply hostile to Britain abandoning those Commonwealth countries which had stood by her in her darkest hour.

In two world wars, New Zealand, Australia and Canada – with India, South Africa and other members of the then Empire – sent thousands upon thousands of troops, airmen and sailors to help save Britain from the Germans.

And during the Second World War, following the fall of Hong Kong and Singapore in 1941, we Australians also had to deal with the Japanese on our doorstep.

Despite this sacrifice, the attitude of the Heath government in the Seventies was “So what?” Government is about the national interest, not emotion. Britain had to make its future in Europe and we could make our futures somewhere else.

I grew up in that environment of hostility towards Britain.

On February 27, 1992, our then Labor Prime Minister (Paul Keating) spoke in Parliament about the shifts in Australian trade and the growing independence of our national outlook and attacking the Conservatives on the other side who were wedded to the “British establishment”.

He said it was important to abandon our:

… links with Britain … the British bootstraps stuff … that awful cultural cringe under Menzies which held us back for nearly a generation … I learned about self-respect and self-regard for Australia – not about some cultural cringe to a country which decided not to defend the Malayan peninsula, not to worry about Singapore and not to give us our troops back to keep ourselves free from Japanese domination. This was the country that you people wedded yourself to, and even as it walked out on you and joined the Common Market, you were still looking for your MBEs and your knighthoods, and all the rest of the regalia that comes with it …

One of his great speeches in fact.

You can read the transcript and watch an interesting video – HERE.

The fact is that when the Macmillan government sought entry to the EEC in 1961, the British assured Australia that there would be no negative effects on Australian trade.

History tells us that Charles De Gaulle vetoed the UKs entry in January 1963 and it was not until he left office later in the decade that the issue of British accession could return.

But in the meantime, Australia was getting used to the fact that it would have to reorient its international focus – that perhaps the cosy world of the Commonwealth was not going to serve our long-term national interests.

Although, I should add that my generation were the first to doubt that it ever served our national interests (as per the speech by Keating above – the full transcript provides much more detail of the issues surrounding our Commonwealth membership and dependence on Britain).

It was acknowledged in the late 1960s that our share of exports to the UK would decline, especially as Australia had long opposed the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) that was the cornerstone of early integration moves in Europe.

Australia had resented the fact that the highly subsidised CAP (remember the butter mountains) had flooded world markets within agricultural products, which suppressed world prices and damaged our relatively unsubsidised farmers.

The CAP also mostly excluded from European markets after Britain joined the EEC. It had further effects which were detrimental to Australia.

For example, the US responded to the CAP restrictions on trade by introducing a sequence of US Farm Bills (from 1973) which provided heavy subsidies to US farmers and pushed down world prices as a result.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics special feature article – Trade since 1900 – provides some good evidence to show the effect on Australian trade.

When Australia became a nation in 1900, the “United Kingdom was Australia’s primary trading partner”:

Total trade with the UK was over five times greater than the total trade with Australia’s second largest trading partner, the United States of America. With the exception of the USA, the other major trading partners were either European countries or members of the British Empire, reflecting Australia’s close historical association with the UK in its developing trading relationships.

The Australian government was most concerned with Britain’s accession.

The Deputy Prime Minister at the time issued a statement (April 26, 1962) – Britain and the Common Market – when Britain first applied to join the EEC, in which he said:

The real issue at stake was the future livelihood of those Australians farmers, miners and factory workers whose-products are largely exported to Britain. Indeed, even manufacturing industry supplying the home market could be affected if our capacity to earn foreign exchange becomes insufficient to provide us with all the raw materials, components and plant which our factories need to maintain their production. The future of whole communities, such as the towns and cities of the sugar producing areas, and the irrigation districts, and isolated mining centres, were deeply involved. In the end result, few Australians would not be affected one way or another.

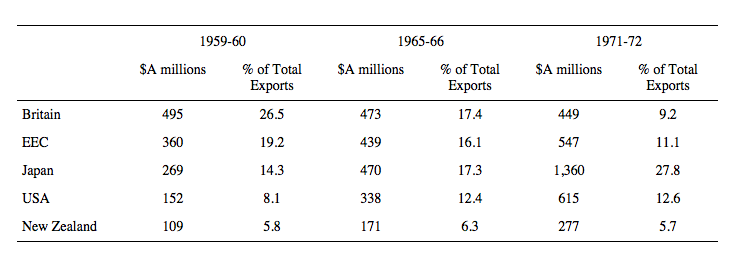

The following table shows the dramatic shift in Australian major export markets as Britain entered the Common Market (it is compiled from Overseas Trade Bulletins published by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)).

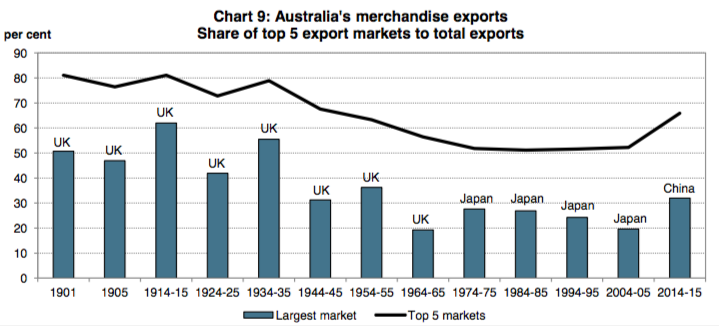

This graph comes from the DFAT publication – Australia’s trade since Federation and shows how profound the shift in our trade patterns were as Britain entered the EEC.

Over the course of a decade or so, “Australia’s export markets also shifted geographically from Europe (especially the United Kingdom) to Asia (especially Japan and China).”

While the decision by Britain to abandon its historical roots with Australia and enter the EEC caused considerable damage to some producers here (some products lost 90 per cent of their market almost immediately once the EU tariff walls went up against them), overall the Australian economy adapted.

As I will show next, the British economy has been in a state of change anyway for more than a decade – shifting away from a reliance on Europe and diversifying its markets.

Much the same pattern that Australia followed once it became clear in the early 1960s that Britain would not give us favourable (or preferential) treatment for much longer.

Trade shifts between Britain and the rest of the world

This graph shows the share of UK exports that go to other EU countries since 1999. In 1999, the EU share of British exports was 54.6 per cent. By 2016, the proportion was just 43.1 per cent.

By the June-quarter 2017 (most recent data), the proportion had risen again slightly.

While the value of exports to other EU nations has risen from £132,929 million in 1999 to £235,838 million, the share has fallen because Britain has increased its total exports to other non-EU nations.

The point is that the EU markets have been a declining relative factor for British exporters long before the notion of Brexit emerged.

The other qualification to this data is that while 43.1 per cent is still a significant proportion, the result is overstated because it includes goods shipped through the port of Rotterdam, which are bound for non-EU nations, but are recorded as going to the EU.

For more information on the “Rotterdam effect”, see the ONS paper (February 6, 2015) – UK Trade in Goods estimates and the ‘Rotterdam Effect’.

ONS conclude that:

Annually, the Netherlands is the UK’s third largest trading partner in the EU … It is also reasonable to assume that trade with the Netherlands suffers from an element of distortion. However, it is not possible to estimate, with any certainty, the impact that the Rotterdam effect has on UK Trade with the Netherlands and its subsequent impact on UK Trade with EU and non-EU countries.

They provide an estimate for 2015 of up to 4.3 per cent difference (lower) for the export proportion if the ‘Rotterdam effect’ is accounted for.

Clearly, Britain has already been fostering other markets for its exports.

Have a look at this graph. It shows historical data for Australia from the fiscal year 1949-50 to 1996-97 (from RBA historical archives) for Australia’s export share by country or bloc.

Concentrate on 1973, when Britain joined the EEC and ditched its agreements with its former Commonwealth partners. While the share of exports to Britain was already in decline, it fell quite sharply at that point once the protection racket that operated in the EEC (particularly the CAP) was applied.

Our access to other EU nations didn’t really change.

But at the same time we started to export more substantially into the rest of Asia (Japan was already a major trading partner).

This sort of shift is possible and dampens any damage to exports that are felt at the time of the divorce.

I will have more trade analysis in later blogs.

British manufacturing booming

I saw the latest – EEF/BDO Manufacturing Outlook 2017 Q4 (released December 4, 2017) – from the EEF, which is the Manufacturers’ peak body in the UK.

The fourth-quarter update is interesting.

We read:

Britain’s manufacturers are ending the year with a bang on the back of the continued improvement in global demand and increased export performance … Manufacturers are continuing to ignore the ongoing political uncertainty at home as improved global demand, from European markets in particular, and the increase in commodity prices is feeding growth across the manufacturing supply chain. This is compensating for weaker UK demand as the squeeze on living standards and Brexit uncertainty continues to take its toll domestically.

So, two observations there:

1. Manufacturing has not been destroyed by the Brexit decision – far from it if the data is to be believed.

2. The UK growth rate is being hammered by domestic demand factors that are totally within the control of the British government to alter if they had the political will.

Brexit is not causing the lull in growth.

The EEF survey reports:

1. “2017 has seen a clean sweep of positive balances across our main output and orders indicators – the rst time this has happened since the nancial crisis.” (post Brexit that is).

2. “The year ended on a strong note, with output and exports response balances holding rm at the multi-year highs reported in the previous quarter.”

3. “manufacturers expect this momentum to carry into the start of next year …”

4. “Our results, in line with the recent past, continue to show improvements in demand conditions across Asian and North American markets.”

However, the EEF also note that the:

Meanwhile the weakness in the domestic market, and in particular the construction sector, though dragging on some sectors

The latest reports on British Construction – for example the UK Construction PMI data (released December 4, 2017) shows that there is little growth in the sector with commercial contracts drying up and the growth being driven by “residential work”.

While there has been hints that this is a Brexit-effect other firms have blamed the “subdued economic outlook” on the decision by British firms to hold back on investment.

After all, if the current productive capital is sufficient to meet current output and sales expectations are weak, then it is unlikely to be a strong investment climate.

Of course, when the non-government sector holds back on investment due to pessimism, that opens up the door for more public investment in foundational infrastructure, as outlined in the UKs recently announced Industrial Strategy.

As the EEF Outlook notes:

… historically the pace of change has been very slow and UK infrastructure appears to be falling behind other leading economies and the demands of the market …

At the centre of our policies for the building of a new economy is investment in smart infrastructure to create the right environment for businesses and local communities to flourish …

Better roads and rail links will give the best return if they connect the regions and the regional powerhouses – helping areas on the cusp of sustainable economic success to cement their position and help their businesses to thrive.

Which means the Construction industry can be revitalised with some smart public sector infrastructure contracts. Again, the capacity to make these policy interventions has nothing to do with Brexit.

That is, any attempts by the EU to declare government projects as breaching the single market guidelines should be ignored by the British government.

The whole purpose of Brexit is to get away from stifling rules that prevent the UK government using its currency-issuing capacity to advance the well-being of its people.

Conclusion

As time passes, it becomes clearer that the June 2016 British Referendum decision to leave the EU has not had the disastrous impacts predicted.

I know people will still say that we have to wait until the full effects are observed. Fair enough. But the disaster scenarios that more or less predicted immediate collapses have clearly been wrong.

And trends such as in British manufacturing are clearly defying more medium-term projections of disaster.

Where there are negative signs in the British economy at present – suppressed domestic demand, decaying infrastructure etc – we can trace that to a long period of austerity and a failure of the British government to use its currency properly.

Obviously there is some shocks going on as people anticipate Brexit. Australia went through that when Britain went into the EEC. But those shocks are likely to be temporary and, as is already happening, Britain is reorienting itself to the wider world away from Europe.

Australia did that pretty quickly.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Although GDP and unemployment may not have been adversely affected, the inflation figure and sterling devaluation percentages have both been *worse* than predicted in the report – the latter probably accounting for the export boom.

It would indeed be wonderful if a (Labour?) Government maximised the full potential offered to it post-Brexit. Unfortunately, that day seems some way off, and in the meantime we are facing huge cuts in local authority spending next April, which will see the characteristically Tory scenario of private wealth vs. public squalor put on steroids. It’s very depressing.

“the latter probably accounting for the export boom.”

That’s sort of the point. The same people moaning about inflation and currency are usually the ones who also moan about current account deficits.

Yes, indeed. The same people who moaned about “the deficit” and “the debt” whilst at the same time fighting to get hold of Osborne’s 4% Granny Bonds.

OTOH, Neil, I thought exporting our goods wasn’t necessarily a good thing?

i.e. Why spend our productive time and effort making stuff for foreigners when we can send them little pictures of QEll in return for stuff that they go to lots of trouble to make for us?

Very interesting. Such a contrast to Simon Wren Lewis’s analysis of Brexit. He claims that Brexit has caused great damage and the exchange rate adjustment can’t be viewed as anything other than damage. I’m left bewildered by the stance of people such as Simon Wren Lewis. To read his blog, Brexit comes across as flat-earth moronicism at best and evil at worst. It seems to tap into a very raw nerve.

@Stone,

To be fair, the lower exchange rate has made life a little bit tougher for the demographic that enjoys agreeable European city breaks, exotic long haul trips, or visits to their Mediterranean villas and Provençal cottages.

However, I’m fairly certain that, unlike SWL and his cohort, this is a burden unshared by the majority of Brexit voters.

Dear Bill

Let me just make 2 brief comments:

1 – While Britain is a member of the EU, it isn’t a member of the Eurozone. By having its own currency, Britain enjoyed an advantage which Spain and Italy didn’t.

2 – Although Britain has voted for Brexit, it is still a member of the EU. It has initiated divorce negotiations, but it is still married. We can’t be sure at this stage how Britain’s economy will fare after the real divorce takes place. it is likely that some industries will contract. Even if other industries expand, such contraction will involve dislocations, which are never deducted from GDP.

Regards. James

James Shipper

You are quite right to raise these two caveats.

Worse, the UK is likely to continue to be hampered by the terms of the treaties for some years after Brexit during the transitional period. Supposedly this will be two years, so we’ve still got at more than three years before we get out of jail.

Even worse, it depends on what the terms of the eventual deal are, and I fear they will be that Britain agrees to continue to adhere to all the current legal requirements of being a full member – without having any say as to what they are. This may well include the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Lisbon) which severely limits member states from using their capacity as currency issuers. After all, if Britain does not agree, it will have a clear advantage over the member states, particularly those who are members of the eurozone.

My preference was for a clean overnight break.

This international law stuff should have been ignored.

A clean break would have meant everybody’s heads would have been knocked together much sooner.

I am not convinced about the relevance of the ‘divorce’ between Australia and the UK in the ’70s to Brexit in the early 21st C, as the two periods do not seem to be that comparable. Any problems I have, however, about Brexit have nothing to do with economics, for Bill is right that the economic doomsayers are likely overstating their case. And Bill is also right about the democratic deficit in the EU structure. My issues are more social, cultural, and political.

This period reminds me strongly of a similar debate in the US in the ’60s and early ’70s, which I have mentioned before. When you criticized anything at all about the US government, you were told to either love it or leave it. I thought that was bogus then, and a similar argument is, I think, bogus now. (I am not, in making this point, suggesting in any way that Bill is putting forward such an argument — others have, hence its inclusion.)

There is also a historical analogy to this debate, though I would not wish to push it too far. And it is that in 1920s Germany, you could reasonably assert that leaving was unnecessary, while in the 1930s, it was clear, to many, that if you could leave, it might be best.

The point I am making is that in the 1930s, it might have been clearer that a change for the better, in this case greater democratization, was unlikely to happen, while in the 1920s, it would not have been ridiculous to believe in a rollback of the Nazi tide and its authoritarianism. Many in the, now we realize deluded, German elite believed this would happen. The Nazi advance in that period was a more or less direct result of their policies. German and Italian Nazification can not be considered to be quite like what is taking place now. So, while historical periods do not repeat themselves identically, there are disquieting parallels.

The disanalogy to my first two points is that they apply principally to individuals, not to a nation state leaving an organization of nation states. But by extension, it could be argued that they have some relevance. Though, as I said, I would not like to push this too far.

Hence, while Bill’s economic and anti-democratic deficit arguments are on the money, as it were, it does not, I think, go far enough. Moreover, bringing the Eurozone into the mix is not, I think, really relevant to the issues under consideration.

James brought up the Eurozone, not Bill. I should have made that clear.

The main point, is, I think as Prof. Mitchell puts it:

‘The outcomes of Brexit will be in the hands of the domestic policies that follow. Stick to neoliberalism and there will be a disaster. But the opportunity is there for British Labour to recast itself and seize the scope for better public infrastructure, better services and stronger domestic demand. Then the nation will see why leaving the corporatist, austerity-biased failure that the EU has become was a stroke of genius.’

I suspect it will be the ongoing ‘disaster.’ No paradigm shift is happening and we have a divided country with the ‘I’m-alright-jack’ voters (about 40%) wanting to keep the Tories in and very little movement unless Labour can unlock the non-voters.

Great article except for one small problem: Brexit has not happened yet. Other than that, great work.

I await your follow-up article, “Sun Explodes and Earth Still Doing Fine” based on physicists predictions for the sun engulfing the earth in a few billion years.

Quote:

Nigel Hargreaves says:

Wednesday, December 13, 2017 at 22:41

.

“Even worse, it depends on what the terms of the eventual deal are, and I fear they will be that Britain agrees to continue to adhere to all the current legal requirements of being a full member – without having any say as to what they are. This may well include the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Lisbon) which severely limits member states from using their capacity as currency issuers. “

…

This is my main worry. If the people negotiating Brexit from the UK side were looking at it through an MMT “lens”, then they would hopefully do their best to ensure that whatever deal the UK ended up with, our capacity as a currency-issuer would not be impaired. Unfortunately, the people we are in fact cursed with are blinkered neoliberals and deregulators.

Going back to Bill’s intro, it wasn’t only the Australians (and New Zealanders and Canadians…) who were disappointed that we had abandoned our Commonwealth friends, family, and allies. Many Brits felt that quite deeply as well. Especially those of my parents generation, who tended to think of Europeans as a mixture of former enemies and unreliable allies (with exceptions made for e.g. Norway & Denmark, with whom we were already partners in EFTA, and romantic memories of “plucky little Belgium” supposedly for whom we had entered WW1).

My generation saw things slightly differently, not having had to suffer WW2, and generally saw “The Common Market” as a good thing, and wanted to get closer to Europe. In many ways, I still think our instincts were correct, but we didn’t know where it was going to lead, or what we would find ourselves getting into.

There is one little issue here. I think that there will be no “effective” Brexit and even a symbolic one seems quite remote – may never happen or there will be an eternal transitional period. It is just enough not to do anything, muddle through and the old regulations and old system will stay in place. Businesses don’t want to have trade barriers or lose access to cheap migrant labour from Central Europe. The City of London wants to retain its role of being the place where credit is created and interests charged on loans, where shares, currencies and derivatives are traded. The number of “Europhiles” among the ruling oligarchy is high enough. The pan-European consciousness among the so-called progressives is strong as ever … The yesterday’s vote proves my point. And the referendum… everyone knows that it was hacked by Putin…

There was a fascinating interview this evening on BBC 2 Newsnight with Sir Richard Dearlove, a former head of MI6. He’s not the sort of person I’d normally spend much time listening to, but, as was pointed out, he’s a copper-bottomed member of the UK establishment, and unusually for such a person, is quite strongly pro-Brexit.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b09jbbj1/newsnight-13122017

(Unfortunately, that will not be available outside the UK, but hopefully it will be adequately covered by the BBC News website, and who knows, maybe even by The Guardian).

(looking at both sites just a minute ago, er, maybe not, at least so far).

“he only good thing about the Treasury Report was that it was “Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum” but even then it was a waste of real resources.”

Elbow from the top rope.

Thanks for this article. Young person like me who are not in economics (which you don\’t want us to go into anyway) just don\’t get any exposure to trade adaptation you talk about in this article.

Can you use some colors that are friendly to color blind people? I am red green color blind and so I totally can\’t see the difference in color between three curves in the Australia export share graph! (other EU, Japan,and other Asia curves). I will just take your word for it on those =). Otherwise, I will have to whip out Microsoft paint and use the dropper to figure out which curve is which. =)

OMG ! Larry Elliot references Bill Mitchell and Reclaiming the State

Think our governments can no longer control capitalism? You’ve been duped

Elliott does refer to Bill and Fazi, but at the end of the very next paragraph, Elliott says this: “using taxpayers’ money to top up poverty wages through tax credits”. He seems to be referring to FDR’s reforms and whether FDR used taxpayers’ money or not depends on when, for around 1934 the US went off the gold standard after which the notion of taxpayers’ money became inapplicable. There have been times when Elliott has referred inaccurately to taxpayers’ money referring to present times. How can Elliott’s reference to Bill and his use of taxpayers’ money be reconciled? Elliott is referring to Bill’s political analysis and not his economic one, hence, his macroeconomics is not involved.

@Expat,

“Great article except for one small problem: Brexit has not happened yet. Other than that, great work.”

To quote Bill above, and the title of the graph:

“The aim of the Report was to quantify “the impact of that adjustment over the immediate period of two years following a vote to leave”.

In other words, the impact over the current period we are in, post Brexit vote, but pre- actual Brexit.

Dearlove interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrCRkyl7CZg from Newsnight