I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

ATTAC should drop the ATT part!

Last Thursday evening in Madrid, I was invited as a guest of the local ATTAC chapter to talk about the Eurozone at a public meeting. I say guest, because one would be excused for thinking that the local ATTAC President was in fact the guest given that he launched into a 25 minute diatribe, masquerading as the first question after my presentation, that attacked Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) for (allegedly) ignoring taxes (no: we just say they do not fund spending) and basic income (no: we just prefer employment guarantees). While it was obvious he hadn’t actually read my book (despite claiming to be commenting on it), he also claimed that I was just another apologist for capitalism and had failed to advocate any fundamental changes to the system. It was quite a performance as you might guess, but I thought it rather odd that the president of ATTAC, which takes its name from its principal advocacy of a Tobin Tax (financial transactions tax), a small little surcharge on the Wall Street excesses, rather than a head-on attack on the legitimacy of the financial markets in general, would dare criticise others for advocating policies within the capitalist realm. I have long written about the need to control financial speculation via regulation rather than through the ‘price system’ (by taxing it). Those who think that working through the price system is the way to change behaviour are operating within neo-liberal logic. It is much more effective to just work through the legal system and ban something that is damaging to the prosperity of nations. That is the MMT position on these financial market excesses – where they just involve wealth shuffling and serve no productive purpose, the state should just legislate them into oblivion. But the so-called revolutionary ATTAC (if my understanding of the president’s ravings were correct) just wants to impose a small tax on Wall Street. And, I guess they will have to go looking for the cash in Panama or somewhere!

ATTAC stands for the Association pour la Taxation des Transactions financière et l’Aide aux Citoyens or in English, the Association for the Taxation of financial Transactions and Aid to Citizens. It began life in France in 1998 and became the principal promoter of the idea of the Tobin Tax.

The Tobin Tax was outlined by the late James Tobin, a mainstream economist in this paper – A Proposal for International Monetary Reform – which was published in the Eastern Economic Journal, Volume 4, 1978.

However, as the paper notes, he first proposed the idea in 1972 as a way of dealing with the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates and the fears that global capital flows would damage economies with the new floating exchange rates.

He actually considered the issue not to be whether the exchange rate was floating or fixed to be the issue.

He said:

I believe that the basic problem today is not the exchange rate regime, whether fixed or floating. Debate on the regime evades and obscures the essential problem. That is the excessive international – or better, inter-currency – mobility of private financial capital. The biggest thing that happened in the world monetary system since the 1950s was the establishment of de facto complete convertibility among major currencies, and the development of intermediaries and markets … to facilate conversion. Under either exchange rate regime the currency exchange transmit disturbances originating in international financial markets. National economies and national governments are not capable of adjusting to massive movements of funds across the foreign exchanges, with real hardship and without significant sacrifice or the objectives of national economic policy with respect to employment, output, and inflation. Specifically, the mobility of financial capital limits viable differences among national interest rates and thus severely restricts the ability of central banks and governments to pursue monetary and fiscal policies appropriate to their internal economies.

While attempting to neutralise the issue about the type of exchange rate regime, Tobin failed to mention that trade imbalances on the current account were much harder to deal with under a fixed exchange rate systems than under flexible rate system, where they are effectively irrelevant.

Domestic policy choices are constrained for a nation with a current account deficit operating under fixed exchange rates (such as the Bretton Woods system) because the central bank has to increase interest rates to offset (via the capital account) the downward pressure on the currency arising from the excess supply of the domestic currency into the foreign exchange markets (to facilitate the excess of imports over exports).

Further, fiscal policy for such a nation has to be restrictive to reduce national income and suppress import expenditure to achieve the same purpose.

So under fixed exchange rates, a nation running a current account deficit faces a chronic bias toward recession and elevated unemployment levels.

Thus, the choice of exchange rate regime does matter, which is why MMT supports flexible exchange rates – they allow maximum flexibility to domestic policy setting to ensure it is as Tobin notes – pursuing the objective of national economic policy.

However, he was correct to point out the destabilising impacts of large speculative flows across national borders and between currencies.

He proposed that there were “two ways to go” towards resolving this problem.

1. “a common currency, common monetary and fiscal policy, and economic integration” – which he dismissed as being “not a viable option in the foreseeeable future”. The designers of the Eurozone should have heeded his words. They created a common currency but ignored the rest of the commonality noted.

Their attempt at reducing the problems of fixed exchange rates between the Member States of the EEC was to create a dysfunctional mess where the trade imbalances persist but the way of dealing with them is austerity (aka ‘internal devaluation’), which is proving to be worse than the bias to recession that plagued many European nations during the Bretton Woods system and beyond (the snake, ERM etc).

2. “greater financial segmentation between nations or currency areas” – which he considered to be “throwing some sand in the wheels of our excessively efficient international money markets”.

His specific proposal (the ‘sand’) was to impose:

… an internationally uniform tax on all spot conversions of one currency into another, proportional to the size of the transaction … The impact of the tax would be less for permament currency shifts, or for longer maturities.

His summation of the effectiveness of the policy was ‘modest’. He thought it would encounter “difficulties of administration and enforcement”.

He thought, at best, it would “restore to national economies and governments some fraction of the short-run autonomy they enjoyed before currency convertibility became so easy.”

But, he concluded that “It will not, should not, permit governments to make domestic policies without reference to external consequences”.

In that regard, he advocated increased international policy coordination, and noted that it was largely absent when the experiences of the US, Germany, Japan (etc) were concerned.

The Member States of Europe found it hard to get Germany to co-operate under the Snake and the ERM. The latter largely undermined those systems because to support the agreed symmetrical adjustment, the Bundesbank would have been selling marks into the foreign currency markets to reduce its value – a requirement that came directly into conflict with its long-standing paranoia about inflation.

As a result, Germany reneged on those agreements (subtlely) and the fixed exchange rate arrangements regularly collapsed as a consequence.

The unproductive financial services sector

In October 2009, the Austrian Institute for Economic Research (WIFO) released a discussion paper – A General Financial Transaction Tax: A Short Cut of the Pros, the Cons and a Proposal (English version), which discussed the costs and benefits of a Tobin Tax.

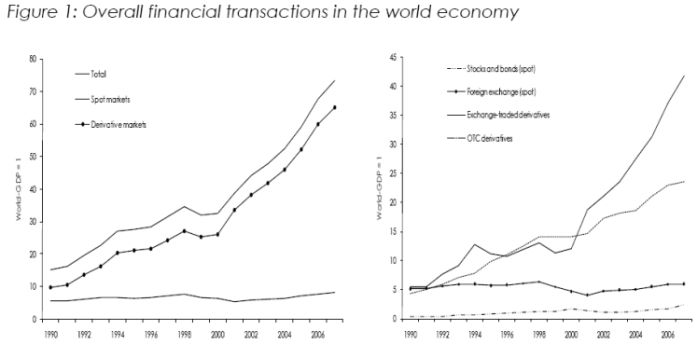

They began with Figure 1 (reproduced below) and suggested (among other things) that:

1. “There is excessive trading activity (= liquidity) in modern asset markets due to the predominance of short-term speculation”.

2. There is a “”predominance of speculation over enterprise” (Keynes, 1936)” which “dampens economic growth and employment.”

3. A Tobin Tax would increase “the costs of speculative trades” and “have a stabilizing effect on asset prices …”

4. It would “would provide governments and/or supranational organizations with considerable revenues which could/should be used for fiscal consolidation and/or the achievement of policy goals, particularly on the supranational level.”

Although the lines are a little hard to distinguish on Figure 1 (I went back to the original OECD data to make sure I knew what was being depicted), the graph shows the explosion of global financial flows and derivative markets over spot markets.

WIFO described this dominance as follows:

Observation 1: The volume of financial transactions in the global economy is 73.5 times higher than nominal world GDP, in 1990 this ratio amounted to “only” 15.3. Spot transactions of stocks, bonds and foreign exchange have expanded roughly in tandem with nominal world GDP. Hence, the overall increase in financial trading is exclusively due to the spectacular boom of the derivatives markets …

Observation 2: Futures and options trading on exchanges has expanded much stronger since 2000 than OTC transactions (the latter are the exclusive domain of professionals). In 2007, transaction volume of exchange-traded derivatives was 42.1 times higher than world GDP, the respective ratio of OTC transactions was 23.5% …

In other words, most of the financial flows comprise wealth-shuffling speculation transactions which have nothing to do with the facilitation of trade in real goods and services across national boundaries. This is significant and conditions what my conclusions are later.

Three points to go on with:

1. If some activity is unproductive then it is better to eliminate it rather than allow it to persist.

2. If the same activity is actually damaging to the real goals of the society – employment and income growth for all – then it is definitely better to eliminate it rather than just tax it to make it a little smaller – although how effective such a tax would be is moot. I think that there would competing tax jurisdictions developing which would render the tax ineffective, but that is not the substantive nature of my concern here.

3. If the tax is being imposed to ‘raise revenue for government’ to allow it to provide better infrastructure then clearly this aspiration lies in the neo-liberal paradigm that erroneously claims that national governments that issue their own currency are revenue constrained.

BIS research on financial sector size

At present, the financial services sector in Australia has been equivalent to around 10 per cent of GDP and over the last two to three decades, that sector has grown been the fastest growing sector.

There has been research published in recent years from the Bank of International Settlements that suggests that the expansion of the financial sector beyond a certain point becomes destructive.

In the July 2012 BIS Working Paper No 381 – Reassessing the impact of finance on growth – we learn that:

1. “at low levels, a larger financial system goes hand in hand with higher productivity growth. But there comes a point – one that many advanced economies passed long ago – where more banking and more credit are associated with lower growth.”

2. “faster growth in finance is bad for aggregate real growth. One interpretation of this finding is that financial booms are inherently bad for trend growth.”

3. “The faster the financial sector grows” the lower is productivity growth (and therefore growth in living standards).

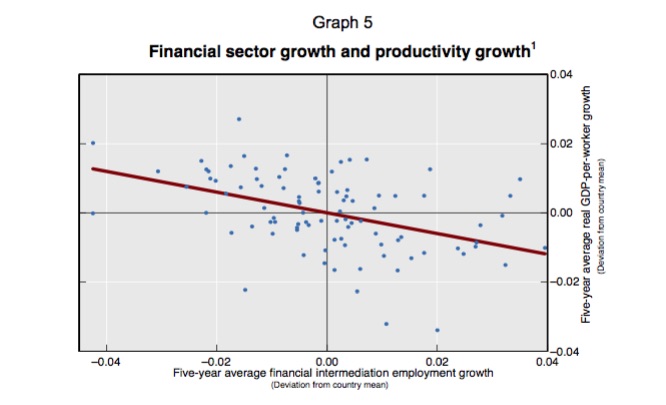

They produced a graph (Figure 5) which on the vertical axis shows “the five-year average GDP-per-worker growth” and on the horizontal axis “the five-year average growth in the financial sector’s share in total employment” for 21 OECD nations between 1980 and 2009.

The BIS authors conclude that the “result is quite striking: there is a very clear negative relationship”.

The BIS researchers examined the two extreme Eurozone countries (Spain and Ireland) in terms and growth of the financial services sector and said that:

During the five years beginning in 2005, Irish and Spanish financial sector employment grew at an average rate of 4.1% and 1.4% per year, while output per worker fell by 2.7% and 1.4%, respectively. Our estimates imply that if financial sector employment had been constant in these two countries, it would have shaved 1.4 percentage points from the decline in Ireland and 0.6 percentage points in Spain. In other words, by our reckoning financial sector growth accounts for one third of the decline in Irish output per worker and 40% of the drop in Spanish output per worker.

The overall conclusion is that “Overall, the lesson is that big and fast-growing financial sectors can be very costly for the rest of the economy. They draw in essential resources in a way that is detrimental to growth at the aggregate level.”

How big is too big?

Once the financial sector exceeds around 3.9 per cent of GDP the negative effects start multiplying.

The BIS authors noted:

… that in most countries, the financial sector’s share in total employment is below or significantly below the threshold beyond which the effect on GDP- per-worker growth turns from positive to negative.

See also the results in the February 2015, BIS Working Paper No 490 – Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?.

The conclusion is that keeping the financial sector small is beneficial – even the mainstream research institutions accord with that inference.

It is highly unlikely that a Tobin Tax will achieve this shrinkage in the sector it targets and therefore will be ineffective in producing beneficial outcomes.

Productive speculation

It would be wrong to consider all hedging and speculation to be damaging. When it accompanies trade flows and provides security to a trading concern then it can be beneficial. When we talk about hedging in this context we are referring to a strategy to avoid foreign exchange risk (sometimes called covering an open position).

Take the example of an Australian manufacturer which exports into the world market. The firm incurs all their costs in $AUD but contracts, say in $USD and has to deliver in say 3 months time whereupon the foreign purchaser will pay them in USD. Any rise in the AUD against the USD in the meantime will damage the firm’s revenue (in $AUD) but not alter its costs – thus the firm is exposed to losses or profit squeeze. Any fall in the $AUD will benefit the firm when it comes time for the foreign buyer to pay up on the delivery contract.

The firm might ‘hedge this exposure’ in the forward exchange markets by buying a contract to sell $USD at a preferable exchange parity against the $AUD in 3-months time. So say it had worked out that a $USD rate of $AUD1.20 would be profitable then it will seek a 3-month forward contract to sell the contract amount of $USD at that rate.

So in 3-months the firm will get the contract amount (say $USD1000) and sells it to the counter-party at the agreed rate for $AUD (thus, $AUD1200) thereby avoiding all exchange rate exposure.

The same sort of arrangement might benefit an importer who has to deliver foreign exchange at some future date.

Whatever the basis of the contract, a counter-party (the speculator) is required to insure the hedger. While the hedger is willing to pay to cover its foreign exchange risk. the speculator accepts the foreign exchange risk (an open position) and hopes to profit from the contract.

In the case above, if the $AUD appreciates in the 3-month period (say to $AUD1.10) then the speculator who has to deliver $AUD1200 to the manufacturer at $AUD1.20 per USD has to buy $AUD1200 for $USD1091, which means it loses $USD91 less the hedge fee it charges.

If the $AUD depreciates (say to $AUD1.30) then the speculator gains pays $USD923 or the $AUD1200 and gets $USD1000 back, thus making a profit of $USD77 plus its hedging fee.

The important point is that the risk is transferred to the speculator and it is likely that arrangements like this increase the volume of international trade because the trading firm bears none of the risk of the exchange rate exposure involved in the cross-border transactions.

It is more complicated than this but in general this example demonstrates when speculation is beneficial. The common element is when it is helping the facilitate trade in real goods and services which improve material standards of living.

It would be futile to deter speculative behaviour that assists international trade in goods and services even though from a MMT perspective the benefits of trade are evaluated differently.

Tobin Tax – falling into the neo-liberal trap

ATTAC often justifies its advocacy of the Tobin Tax by claiming it will generate much-needed revenue which the governments can use to improve public infrastructure and provide better public services.

While Eurozone governments are revenue-constrained, most governments are not.

A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. Most governments fall into that category.

So the question is: Why buy into the neo-liberal myth that national governments that issue their own currency will improve their spending prospects if they raise extra tax revenue?

Why is ATTAC among other organisations propagating that myth?

Why isn’t it using the AC part of its name (Citizen Action) to demand governments increase fiscal deficits commensurate with the need to increase employment and attain full employment?

The answer is that these organisations are basically trapped in the neo-liberal world that says that currency-issuing governments are like households and have revenue constrained spending.

Better to regulate rather than tinker with the price system

The other question that organisations such as ATTAC and others who propose the Tobin Tax avoid is: Why do we want to allow these destabilising financial flows anyway? If they are not facilitating the production and movement of real goods and services what public purpose do they serve?

A small tax on the flows if it can be levied effectively will only put a small dent in them.

But it is clear that the growth of the financial markets has made a small number of people fabulously wealthy and damaged the prospects for disadvantaged workers in many less developed countries.

More obvious to all of us now, when the system comes unstuck through the complexity of these transactions and the impossibility of correctly pricing risk, the real economies across the globe suffer. The consequences have been devastating in terms of lost employment and income and lost wealth.

So I don’t see any public purpose being served by allowing these trades to occur even if the imposition of the Tobin Tax (or something like it) might deter some of the volatility in exchange rates.

Solution: All governments should sign an agreement which would make all financial transactions that cannot be shown to facilitate trade in real good and services illegal. Simple as that.

Speculative attacks on a nation’s currency would be judged in the same way as an armed invasion of the country – illegal.

This would smooth out the volatility in currencies and allow fiscal policy to pursue full employment and price stability without the destabilising external sector transactions.

A nation could act unilaterally to stop these transactions crossing its own borders. Capital controls could also help.

The proposal to declare wealth-shuffling of the sort targeted by a Tobin tax illegal sits well with the other financial and banking reforms I have discussed in these blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks .

So it turns out that MMT is a much more progressive approach than those advocated by ATTAC.

Conclusion

The Tobin Tax is another one of those traps that ‘progressives’ fall into thinking they are getting one back for the people from ‘Wall Street’.

While the financial sector operators are likely to get around the tax anyway, the better approach is to legislate these unproductive and damaging services and products out of existence all together.

Fiddling with the price system (via a tax) implies a recognition that these activities should exist but be reined in a bit.

I hold the view that these services/products should not exist. I think that is a more consistently progressive position than one that tries to play smart with the price system.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What a great way to welcome a guest! It’s actually kind of funny 🙂

Much to your credit that you presumably didn’t walk out of the meeting there and then. I would have. How on earth did you manage to follow that diatribe?

Bill

i have a question lets say a big country like u.s if it will have a purpose to ban internationally the use of unproductive sspeculation its have the tools to stop it? (if lets say other countries and tax havens will not agree)

Dear Bill

Speculation is simply a synonym for betting. A speculator is not different from a guy who bets on a horse or football team. Speculation isn’t productive, but neither is betting. The difference is that betting will never distort the economy. The case for restriction or prohibition of speculation must not rest on its unproductivity but on the harm that it does to the rest of the economy. Much of the financial sector simply provides luxury services to the wealthy. It can be compared to the manufacturing of Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Jaguars. We don’t prohibit those luxury cars either. As long as there are rich people, there will be luxury services and products. They should be forbidden only if they harm the rest of us.

Regards. James

I lived through the period after Nigel Lawsons’ “big bang” of 1987 in the UK. I was fortunate in having bought a home in 1978, when the banks were still heavily regulated and building societies were heavily restricted to creating money for mortgages only three or so times incomes, and needed large reserves, including two year savings accounts.

You do not have to be an economist to appreciate how the crazy lending drowned young people in debt after the big bang, giving them 100+ percent mortgages several times their incomes and seeing the subsequent booms and busts, negative equity and forclosures that started in the early nineties. The efficiency with which banks extract interest and destroy peoples incomes and wealth, while at the same time conning those that keep their property that they are making money out of rising prices is still not properly perceived by most people. Bank regulation is the answer, but while the Tory Party and others around the world get donations from them it is unlikely to happen until people realise what is going on. I cannot see how taxes on banks can help if the banks are creating too much debt in the first place and destroying the bulk of peoples incomes.

I agree with Bill. Asset side regulation in regards to banking – in other words if a loan does not fit certain criteria it becomes a gift – is better than changing the price of lending. Lending needs to be tailored towards capital development.

Neil Wilson has a very good article on banking in terms of changes to the UK system:

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2013/05/making-banks-work.html

I totally suscribe Bill´s words . My apologies for Ricardo´s behaviour. As a former member of ATTAC Spain Coordination Table(MCAE), I left the coordinaton of global fiscal and financial comission few months ago, I have to say about ATTAC Spain : FIRST Ricardo is not the President of ATTAC Spain ,SECOND ATTAC Spain is prural , indeed we have formed a subcomission called Monetary Sovereignity mainly based in MMT knowledge, THIRD In my opinion we have stucked in the 90´S,for ATTAC it´s time to evolve and MMT is a powerful tool , so Bill´s advice I think is pertinent.

“All governments should sign an agreement which would make all financial transactions that cannot be shown to facilitate trade in real goods and services as illegal.simple as that”

Well that sounds a unlikely and unfeasible as a well managed Monetary and fiscal union between different countries.Not to mention that even if an agreement was reached it would be near impossible to enforce.

…it will interesting to read 490 to know exactly why a growing finance sector ‘crowds out’ real economic growth.

Dr. Bill,

“”A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.””

SOooooo….. “because it is the monopoly issuer of currency””, unlimited sovereign government revenues are declared, ……. as a fact.

It would seem a better-founded statement to be that “IF the sovereign government IS the monopoly issuer ……”” such that, just in case it is NOT the issuer, THEN, no unlimited revenues, and thus, the need to tax, even borrow perhaps ..etc.

By defining the exception of the EMU, it is clear that sovereignty alone cannot be the vehicle that enables certain money-issuance powers by a government. So where is the money power? The EMU accords imply the potential for power-diminishing tools in the form of legislation that are designed to specifically limit the sovereign’s money-issuing power.

Thus, the above seems an over-reach statement – that being the monopoly issuer of the currency (money supply as however defined) is axiomatically “caused by” being sovereign. An inseparable tenet is implied. However, other potential conclusions also advance …… and from observation more than theory.

BESIDES the EMU, there are many countries that remain sovereign despite the fact that their governments have, through legislation, empowered private international bank-corporations with the privilege of issuing that which serves as the national money supply, this despite the fact the ultimate authority over money power remain where sovereignty places it …. with the people, acting through their governments.

“”Most governments fall into that category.””

My take is there is a missing link not in evidence to the claim that every ‘sovereign’ government – by its authority and power – IS issuing the currency …..with ‘currency’ being the operative term of what is, in fact, for all political-economic discourse, pretty much ….. the money supply.

So, to close that loop, any sovereign government that has delegated through Acts and legislation its money-issuance POWERS to anyone, EMU or International Bankers, DOES need the money that it receives(taxes and borrows) in order to fund its spending programs.

Australia ?? Sovereign money-issuing government, Bill?

By what power and authority?

Thanks.

Bill –

Why do you favour the bureaucratic authoritarian solution?

And why do you label it the MMT position?

Surely MMT shows us that a government can always prevent a collapsing company from triggering an economy-wide disaster? So why impose restrictions on what people and companies can do with their own money?

Obviously banking regulation is still needed, and I can see why you’d want to regulate CDSs, but why restrict access to CFDs?

Rather than throwing sand in the wheels, I think we should throw in graphite. An efficient market is a good market! And if the financial services sector is unproductive, we should short circuit it: lower the barriers to entry. Then if the private sector are still inefficient, set up some public sector organisations to compete.