I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Changing private investment activity requires higher fiscal deficits

I read an interesting paper this week from the US Federal Reserve Bank – The Corporate Saving Glut in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis – written by Joseph Gruber and Steven Kamin. It was published in October 2015 as part of their International Finance Discussion Papers (Number 1150). Essentially, the paper documents a rather substantial “increase in the net lending … of non-financial corporations in the years preceding and especially following the Global Financial Crisis”. Their results cast doubt on the notion that the decline in productive investment over the last 15 years or so reflects a desire by firms to “strengthen their balance sheets”. These trends have significant implications for how we view fiscal positions and the normality or otherwise of particular deficit or surplus outcomes. The authors do not tease out those implications so I thought I would.

The research paper considers the so-called “corporate saving glut”, which they identify as a “potential source of leakage from aggregate demand”.

The saving glut is defined as “the excessive saving over investment among the corporations of many of the world’s leading economies”.

They believe that the glut “could have considerable consequences for economic activity and external imbalances around the world, particularly as it has widened considerably in recent years”.

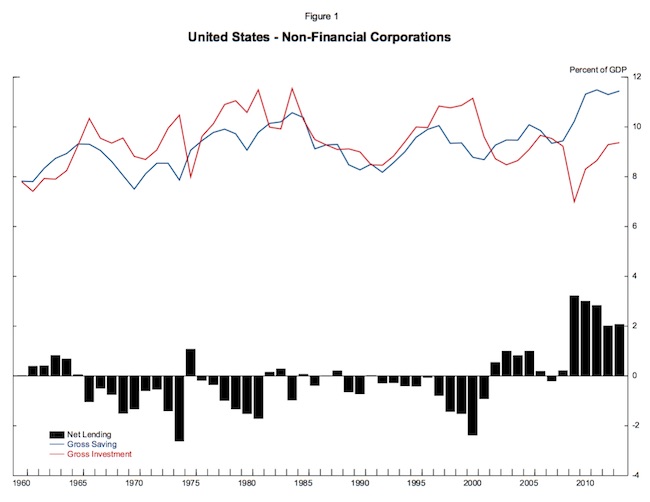

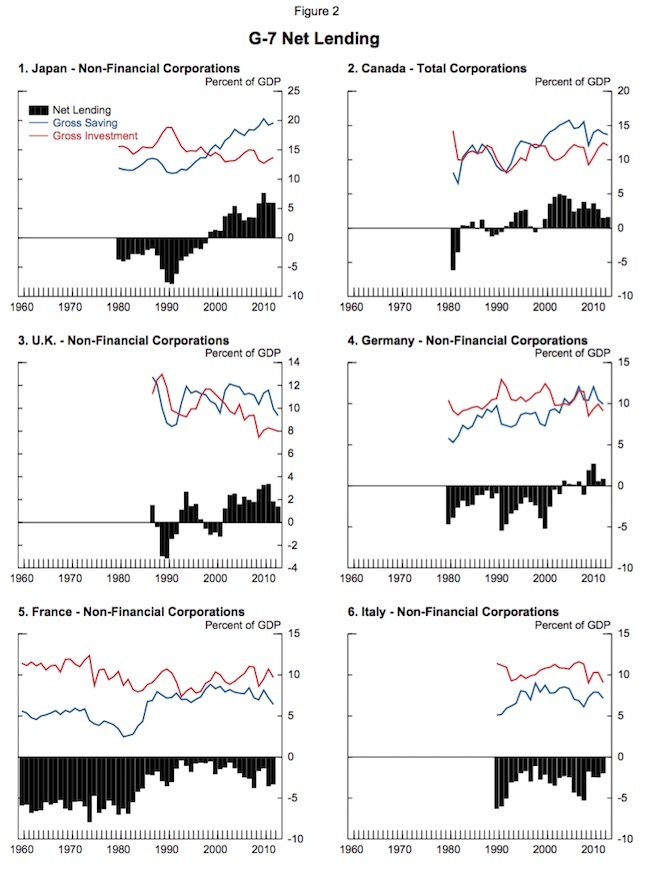

There discussion is motivated by the following two graphs, which are reproduced from the paper.

The first graph (Figure 1 from the paper) examines “the corporate saving glut for the United States”. Here, saving is defined as the “undistributed profits of non-financial corporations” and investment is defined as the “spending by non-financial corporations on capital formation”.

For non-economists, remember that investment in economic jargon is not defined as purchases of financial assets for speculative purposes. Investment has a very specific meaning which is spending that augments productive capacity whether it be on buildings, plant and equipment, or other forms of capital accumulation.

It is clear from the graph that prior to 2000, “non-financial corporations borrowed on net from the rest of the economy to finance their investments, as indicated by their negative net lending rates”.

From 2002, the situation changed and the “small positive net lending positions” that emerged have since “ballooned after the global financial crisis”.

The second graph (Figure 2 from the paper), Shows that the “In other G7 economies, corporations switched from net borrowing to substantial net lending positions even earlier … Only in France and Italy has let lending remained negative”.

The paper also provides information that shows that non-financial corporations also increased their “holdings of cash and other liquid financial assets” after the GFC.

They then show a sequence of graphs which show that:

1. “countries with the greatest shortfall in recent growth have tended to experience larger increases in corporate lending”.

2. “increases in corporate net lending since the GFC are correlated with higher current account balances, suggesting that higher corporate saving has not been offset by lower saving in other sectors of the domestic economy”.

3. “in countries where corporate net lending has risen since the GFC, households have reinforced this drag on demand through similar adjustments of their own”.

The question that needs to be answered is “why increases in corporate net lending and a weakening of aggregate demand have coincided in many countries”.

There are many different possibilities that the paper wishes to examine:

1. The behaviour “simply reflects cutbacks in investment spending in response to the recession and subsequent slow economic growth”.

2. The behaviour may be driven by extreme caution by corporations after the GFC, which has seen them “boost net lending in order to accumulate financial assets and bolster their balance sheets”.

3. The behaviour may be driven by a sense that “firms do not perceive suitable investment opportunities, even with interest rates being extremely low and growth rates of GDP back near more normal levels”.

I won’t discuss their methodology in any detail and you can consult the original paper if you are interested. Essentially, they seek to “evaluate whether the shift in the allocation of corporate profits … principally reflected the typical reaction of investment profits to … notably weak economic activity and exceptionally low interest rates – or whether the shortfalls in investment spending and increases in payouts to investors and asset accumulation may have been unusual …”

Their results can be summarised as follows:

1. The substantial rise in non-financial Corporation net lending “started even before the GFC”.

2. Using statistical models that seek to explain firm investment behaviour, they find “that investment in the major advanced economies has indeed weakened relative to what standard determinants would suggest, but that this process started well in advance of the GFC itself.”

3. They “find that the counterpart of declines in resources devoted to investment has been rises in payouts to investors in the form of dividends and equity buybacks”, which “suggests that increased risk aversion and a precautionary demand for financial buffers has not been the primary reason firms have cutback investment”.

4. They conclude that “there has been a decline in what firms perceived to be the availability of profitable investment opportunities”. This finding is consistent with the literature on secular stagnation that has arisen in the last few years.

The Federal Reserve paper does not seek to investigate “what is causing this paucity of investment opportunities, and what are its implications for future investment and growth”.

They are clearly aware that this is a ongoing research program.

What is causing the reduction in profitable investment opportunities is one question. The other is whether governments can do anything about it.

Please read my blog – The secular stagnation hoax – for more discussion on this point.

The secular stagnation claim posits that we are facing a long-term future of lower growth and elevated levels of unemployment and there is not much we can do about it.

The only problem is that, while it seems to be a new explanation for the low growth that nations are locked into now – a sort of flavour of the month intervention to the debate – this hypothesis first entered the economics debate in the late 1930s when economies were still caught up in the stagnation of the Great Depression.

Then like now the hypothesis is a dud.

The problem in the 1930s was dramatically overcome by the onset of World War 2 as governments on both sides of the conflict increased their net spending (fiscal deficits) substantially.

The commitment to full employment in the peacetime that followed maintained growth and prosperity for decades until the neo-liberal bean counters regained dominance and started to attack fiscal activism.

The cure to the slow growth and high unemployment now is the same as it was then – government deficits are way to small.

Reflecting on the graphs above, the change in behaviour after around 2002, provides further evidence that the mainstream economics approach is deeply flawed.

Mainstream macroeconomic theory posits that the corporate sector (or firms in general) “borrows from the household sector to finance capital investment”.

This supposition is important in mainstream theory because in a closed economy model, leakages from spending via household saving are immediately injected back into the spending stream by investment, with the consequence that governments can run balanced fiscal positions without undermining economic activity.

Remember, that a lot of economic reasoning was based upon these closed economy models given that when they were being developed, trade was not as significant as it is today. Further, the US is a relatively closed economy anyway and a number of the textbook developments emerged from that nation.

At the heart of the mainstream conception is the – Theory of Loanable Funds – which is an aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

These are the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory.

The financial system is conceived as the market for loanable funds where household saving is deposited in banks (or other financial intermediaries) and firms then seek to borrow these funds.

The interest rate is set by the relative strength of saving (deemed to be a positive function of the interest rate – higher rates induce households to postpone current consumption and save to enhance their future consumption) and borrowing (deemed to be a negative function of the interest rate – as the cost of funds rises the profitability of marginal projects falls).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called Classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

There is no problem for the economy in households increasing their desired saving. The solution does not rely on private investment improving any time soon, although a rise in capital formation would quicken the pace of recovery.

The leakage from the expenditure stream that occurs as household increase their saving just has to be filled by a rising ‘injection’. In the mainstream approach, this ‘injection’ comes from investment spending which absorbs the increased household saving.

So if non-financial corporations are themselves increasingly becoming net lenders to the rest of the economy then the idea that household saving provides the investment funds for firms has to be questioned.

Further, this shift in behaviour implies a serious new leakage to aggregate demand has developed, which if left unchecked would bias the economy to recession.

The mainstream alternative is that growth is maintained by rising consumer spending by households driven by increased credit. In other words, the lenders and the borrowers have swapped seats.

Of course, such a growth scenario is unsustainable because households cannot cope with ever-increasing levels of debt, as we learned in 2008.

At present, there is a bias in the policy debate towards austerity manifested in fiscal strategies designed to push the fiscal balance into surplus.

It is clear that this strategy is failing because the attempts to reduce fiscal deficits are undermining economic growth, which, subsequently, undermines the growth in tax revenue that the governments projected would drive them back into surplus.

Moreover, this shifting behaviour in non-financial corporations coupled with the observation that household saving out of disposable income is once again rising, after the credit binge prior to that GFC, is redefining what we might consider to be normal.

Prior to the GFC, the private credit binge (largely driven by household borrowing) allowed economic growth to be elevated and in many countries the fiscal position to move towards smaller deficits or in deed, in some cases, into surplus.

Australia, for example, recorded 10 fiscal surpluses between 1996 and 2007 as household debt ratios rose to record levels and economic growth was consistently around or above trend.

The household saving ratio over that period fell to negative values. The household saving ratio has since returned to around 10 per cent of disposable income as households seek to reduce the precariousness of their balance sheet positions.

Even without the drag on aggregate demand from this shifting non-financial corporation lending behaviour, the reversal in household saving behaviour, meant that any strategy by government based upon returning to those fiscal surplus outcomes would be impossible to sustain.

The problem is that the government still attempted to reduce the deficit and economic growth has faltered since that time as a result of the slow growth in domestic spending.

The point is that the household credit binge is over and the government has to return to its normal position of fiscal deficit of varying magnitudes.

The shift in non-financial corporation lending behaviour only magnifies that fact. With households now returning to more normal levels of consumption growth, the slowdown in private investment behaviour has increased the spending gap that the government has to fill.

For a nation with a strong external position, as evidenced by current account surpluses, the necessity for government deficits to close private domestic spending gaps is reduced, if not, eliminated.

In Australia’s case, the external sector acts as a drain on overall demand (spending), which means that the government deficit is both normal and a required outcome of the saving behaviour of the private domestic sector.

As long as the government sector ‘finances’ that rising saving behaviour from the households and firms, economic growth can continue and the paradox of thrift effect thwarted.

The rising net spending promotes income and employment growth, which combine to generate the rising saving capacity desired by the households and firms.

Conclusion

Clearly, if the private firms are reluctant to invest and if rising government deficits are required to sustain economic growth, the shift between public and private resource usage will also alter – that is, larger public sector and smaller private sector.

That is a consequence of these underlying trends that the Federal Reserve Bank research paper has identified.

It may be though, that the perception of a lack of profitable investment opportunities in the non-financial corporation sector is a reflection of the fiscal austerity, which has stifled economic growth and left millions of people unemployed without incomes.

A reversal of this fiscal mindset can easily reduce unemployment and allow the economies to breathe again. In that sort of growth environment, one would expect profitable private investment opportunities to arise more easily.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

Great post.

“and if rising government deficits are required to sustain economic growth”

There’s been some debate about this summary term “rising government deficits” amongst people because it seems to go against the causality flow.

If government isn’t really in control of the size of the deficit, then how can it make it rise?

Of course the answer is that the government has to invest more and improve its spending side auto-stabilisers (aka a Job Guarantee). And possibly tax households or spending less.

But really that is about increasing the flow rate in the economy. A rising deficit would just be a side effect of extra savings from that flow.

Is there a better way of framing “increase the economic flow by government activity” than “rising government deficits”?

The right wing narrative days investment is anti-cyclical when the causation is logically and historically pro-cyclical. Out another way, why invest in capital goods when demand for consumer goods made by them is falling?

In the UK, the latest edition of the Office of Budget Responsibility “Economic and Fiscal Outlook Nov 2015”, has Chart 3.38: Sectoral net lending. It shows the Osborne plan as Bill explains above. The Household and Corporate sectors, financing the government surplus and the net imports from the Rest-of-the-World.

http://cdn.budgetresponsibility.independent.gov.uk/EFO_November__2015.pdf

Bill

Many thanks. Being from the UK, I note the difference in the shape of the graphs between the various countries. In particular, the fact that the UK, seemingly uniquely, have both lines trending downwards (if I am interpreting this correctly). Thus the total available finance available to UK industry (after profits) seems to be declining.

Am I right in this deduction and what might the reason be?

Is it simply that there has been a choice (or a demand from stack holders) to pay increased dividends?

Or could there be some other explanation?

Either way, the reason for the difference needs to be explained.

Neil

A thought

“If government isn’t really in control of the size of the deficit, then how can it make it rise? ”

Governments may not be able to predict the outcome, but surely they do control their discretionary spending; eg on infrastructure etc. If that’s being cut in spite of resources being available then their getting it wrong. At the moment cutting is heading the economy in the wrong direction as all the fat is being consumed by the government and the population is suffering (which will increase). The UK economic resilience is declining so that world events, economically, can do more severe damage than would otherwise be the case.

If the resources are not available surely they should be understanding why not and then trying to increase the total resources available to the economy eg investing in training to ensure the manpower is available

Dear Bill

One reason why the corporate sector has become a net lender in some countries is that many corporations have become much more profitable. The higher the return on investment, the greater the probability that a corporation can dispense with borrowing to finance whatever investments it plans to make.

Another reason may be that the capital/output ratio is declining. Obviously, the lower the ratio, the less investment is needed to maintain GDP at a certain level or to make it grow. Suppose that a corporation has an output of 100 million and 400 million in capital. If, because of technological change, it can bring forth its 100 million with 300 million of capital, then its investment needs fall by 25%.

What about unincorporated businesses? Are they included in the data. The majority of businesses consist of fewer than 10 employees, and many of those are unincorporated.

Regards. James

Bill,

I think you’re being a bit too blase about these issues. Are you aware of William Lazonick’s work? I think that is what generated these debates. He suggests that firms have gone into looting mode on the back of “Shareholder Value Maximisation ideology”. This idea has strong support amongst some in the private equity markets (some of whom follow your work quite closely). See, for example:

https://eic.cfainstitute.org/2014/10/23/shareholder-value-maximization-the-dumbest-idea-in-the-world/

https://www.gmo.com/docs/default-source/research-and-commentary/strategies/asset-allocation/the-world's-dumbest-idea.pdf

Maybe a sharp rise in aggregate demand would solve this. But maybe it would not. The institutional landscape could have changed due to effective class war in the past 40 years. It is definitely worth some thought.

Neil, a candidate for your govt deficits terminological problem could be an emphasis on govt spending. That is, econ flow increases as a consequence of the government spending more, without mentioning the deficit. The problem with finding an alternative phrase is that the opposition will bring the discussion back to the deficit as “the bad thing that must be avoided at all costs” because it conforms to and confirms their narrative. Challenging the Tory narrative will require, I think, more than a terminological adjustment. I wish it were otherwise.

Good post Bill,

Another thing to look at about why countries differ might be to do with private pension provision. In the UK the baby-boomers were blessed with quite generous pension promises from their employers in the past, and many companies are having to strengthen their balance sheets to meet those pension obligations. In countries which rely mostly on state pensions the need for companies to save might be more muted.

Neil,

It might be easier for governments to control their fiscal balance when expressed in absolute terms (i.e. £s, $s etc) than when expressed as %GDP, as an increase in projected net spending of £10bn might be achievable, but knowing how that works out as %GDP would require accurately knowing what the effects on national income would be.

I’m probably wrong.

Kind Regards All

@ Neil

Sure. You just re-frame it as it actually is…a (chronic, systemic and unavoidable) scarcity of individual incomes….that can only be actually resolved by a direct and costless payment to the individual….because if you rely upon simply the indirect method of investment or the costs and inefficiencies of government (which also largely go directly into the system before reaching the individual’s pocket)….you just re-initiate the scarcity.

We require a reformation of economic and monetary theory which breaks down the enforced indirections of government and the productive system itself. That way the blessings of the tool of money and our abundant abilities to produce will serve the individual and the system instead of serving only the top 4-6% who now control it. Somebody needs to nail the 99 theses on the doors of a cathedral.