I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Salary caps on CEOs?

In today’s Melbourne Age there was a headline that attracted my attention – Hurling invective at CEOs over salaries is a bit rich. The writer from the conservative Institute of Public Affairs was reacting to a speech made by the President of the ACTU this week who proposed a salary cap on executives. The writer, Chris Berg claimed this was just whipping up some “traditional class conflict”. He asked: “who seriously believes that the level of CEO pay in Australia had anything to do with the subprime crisis that set off this whole mess?” Well, I for one think that the growth in executive pay was linked to the crisis. Here is the point.

Berg claims that normally, the ACTU’s campaign to get “a salary cap for chief executives of 10 times the wage of their average employee” would:

… be easy to dismiss as the embarrassing post-mortem spasm of a union movement that is cooling in the morgue. A financial crisis is as good a time as any to whip up a little anger about dastardly bosses; a bit of traditional class conflict.

He believes that only should regulate CEO pay are the shareholders who “have just as big an interest in the future of their company as its employees.” He also believes that the rise of CEO salaries is just one side of the business cycle which sees pay fall again “when the market falls”.

His principle point though is that:

you’d hardly call it courageous when politicians and union leaders blame the three or four Australian executives who could be considered uber-rich for the problems the world economy faces.

So are the business classes led by the CEOs (not just four of them but all of them) responsible in any way for the crisis that is causing havoc around the world?

In the 2006 article Heads you win tails I lose!, John Shields notes that:

The 100 chief executive officers (CEOs) who comprise the membership of the Business Council of Australia (BCA) represent the self-proclaimed elite of Australian business leadership … Individually and collectively they have also been in the forefront of the employer campaign for greater flexibility in Australian employment relations, as well as for increased labour productivity and labour cost competitiveness … Since the election of the Howard Government in 1996, the BCA has enjoyed unparalleled access to the corridors of political power and past and serving members of the BCA board have been among the most outspoken critics of the ‘over-regulation’ of Australia’s economy and labour markets … BCA CEOs have enjoyed long-term cash earnings growth far in excess of that of ordinary Australian wage and salary earners … Over the past 16 years, … (t)he rise in BCA CEO cash earnings equates to an average compound annual growth rate of 13.5 per cent (or 10.7 per cent in inflation-adjusted terms) compared to just 4.2 per cent (or approximately 1.4 per cent in real terms) for ordinary full-time wage and salary earners, while the gross cash earnings gap between the two groups has widened from 18:1 to 63:1.

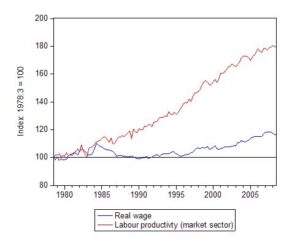

In an earlier blog – The origins of the economic crisis – I provided the following chart which depicts the growth in labour productivity and real wages since 1978. You can clearly see that real wages have failed to track GDP per hour worked (in the market sector) – that is, labour productivity. Real wages fell under the Hawke Accord era which was a stunt to redistribute national income back to profits in the vein hope that the private sector would increase investment. It was based on flawed logic at the time and by its centralised nature only reinforced the bargaining position of firms by effectively undermining the traditional trade union movement skills – those practised by shop stewards at the coalface.

But during this time the government was lobbied heavily by the employer lobby groups (like the BCA) to cut real wages.

Under the Howard years, some modest growth in real wages occurred overall but nothing like that which would have justified by the growth in productivity. In March 1996, the real wage index was 101.5 while the labour productivity index was 139.0 (Index = 100 at Sept-1978). By September 2008, the real wage index had climbed to 116.7 (that is, around 15 per cent growth in just over 12 years) but the labour productivity index was 179.1.

Again these movements were during a period of intense lobbying from the business classes to cut real wages and redistribute income towards profits. The campaign was very successful and the widening gap between labour productivity and real wages represents profits. During the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital.

The successive business-centric Federal governments (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation aimed at destroying the union movement; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the means that legislative support helped redistribute income. The federal government also deliberately held the unemployment rate up at high levels to put downward pressure on wages. All of this was under the watchful eye of the business classes who maintained constant pressure on the governments to keep the redistribution process moving. It is always interesting to go back to the wage cases (in the Australian Industrial Relations Commission) to see how the business advocates argued.

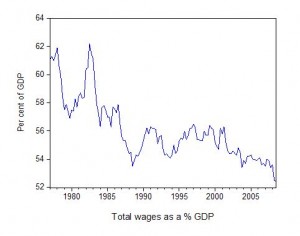

The next graph depicts the summary of the labour productivity-real wage gap – the wage share – and shows how far it has fallen over the last two decades. This trend has been replicated in most advanced economies over the same period. Governments right around the advanced world have been pressured by the business class to participate in the largest redistribution of national income to profits in history.

The only way the that the economy can keep growing during a period when labour productivity is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging behind is through strong budget deficits or through increasing household indebtedness.

The period concerned was marked by increasing fiscal drag due to the government budget surpluses which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector since around 1997. This in itself presented a dilemma for the capitalist classes.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold. But in the recent period, capital has found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals that is the topic of this blog.

The spending gap was temporarily filled by the growth in financial engineering, which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages.

The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure that profits grew and the output was sold.

As noted above the income dynamics and the debt build-up has been a common trend in advanced economies over the last 20 years.

Ultimately, greed got the better of the industry as it sought to broaden the debt base to make even more profits. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis and the unfolding of that crisis has been with us from 18 months or more now.

The business classes never questioned these dynamics as their bloated executive pay packets provided them with consumption possibilities they had only dreamed about in the past.

They never stopped pressuring government to introduce ever new pieces of legislation aimed at speeding up the redistribution of income in their favour.

They never went to the AIRC and agreed that the labour productivity-real wage gap was out of control and needed rectification.

The process only came to a crunching halt when the debt bubble burst and the meltdown began. It was always going to do that once households decided their balance sheets were too precarious.

But the process by which the executive pay grew to lavish levels relative to the pay that the rest of us receive was a crucial part of the underlying dynamics which have precipitated the crisis.

The way forward is clear. The return to deficits is the first step in recovery. Budget deficits finance private savings and are required if the household balance sheets are to remain healthy.

But to have sustained recovery, real wages will have to grow in proportion to labour productivity for spending levels to be maintained with sustainable levels of household debt. The household sector cannot dis-save for extended periods. This proportionality between real wages and labour productivity growth has been a long-term stylised fact (constant wage share). There is no escaping that the wage determination system will have to institute the means to see that this proportionality is restored and the wage share expanded.

This will also require strong employment growth and drastically lower levels of labour underutilisation.

Once we tackle those problems then the capacity for the massive executive payouts both in the private and public sector will be diminished. There simply will not be the real income available to profits in the proportions that has become common during the neo-liberal binge era.

So I would rather approach the matter structurally – get us back to full employment. Have the Federal government purchase all the labour that no-one wants by introducing a Job Guarantee.

Redesign the industrial relations system (that is, get rid of Work Choices Lite) to provide for stronger real wages growth so that it tracks the growth in labour productivity. Then you don’t really need a salary cap on executives because there will not be enough left for them to grab more than their fair share.

Dear Bill,

Wonderful article. The two graphs pretty much tell us all we need to know about how government and big business operate in this country.

Too many Australians cannot find work and those that have work are being taken to the cleaners by government legislation that allows capitalist pigs to exploit workers.

How do they even sleep at night?

Regards

Alan

Although I’m an open-minded person and see where your logic comes from Bill, I sincerely DO NOT believe that the government should have any say when it comes to executive compensation.

I agree with the Berg statement that executive pay is not to blame for the financial crisis. If you want to hold someone accountable, how about the left-wing legislaters in the US who forced the financial instistutions to lower their standards so even the poorest citizens could purchase their own homes?

Cheers