I am travelling today to Tokyo and have little time to write here. But with…

Australian National Accounts – below trend growth continues

Today’s Australian Bureau of Statistics – Australian National Accounts – for the December-quarter 2013, shows that real GDP growth was 0.8 per cent, up from 0.6 per cent in the September-quarter 2013. The annualised growth rate of 2.8 per cent is an improvement on the 2.3 per cent from last quarter but still remains well below the trend rate between 2000 and 2008 of 3.3 per cent. Growth is being driven by household consumption, net exports, and public consumption and investment. Without the contribution of the government sector, overall growth would have been negative over the last two quarters. This contribution, while welcome, will not be sustained given the current political environment. Overall, the data paints a fairly subdued picture for the Australian economy for the last three months of 2013.

The main features of today’s National Accounts release for the December-quarter 2013 were (seasonally adjusted):

- Real GDP increased by 0.8 per cent after recording a 0.6 per cent increase in the September-quarter.

- The main positive contributors to expenditure on GDP were the contributors to expenditure on GDP were Net Exports (0.6 percentage points), Final consumption expenditure (0.5 percentage points) and Public gross fixed capital formation (0.2 percentage points), the same contributors as last quarter.

- The main negative factors were Private gross fixed capital formation (-0.5 percentage points) – the second consecutive quarter of negative private investment expenditure.

- Our Terms of Trade (seasonally adjusted) improved in the quarter by 0.6 percentage points (reversing the recent falls) but in the 12 months to December 2013, they fell by 1.2 per cent.

- Real net national disposable income, which is a broader measure of change in national economic well-being rose by 0.7 per cent for the quarter and 1.8 per cent for the 12 months to the December-quarter 2013, which means that Australians are better off (on average than in 2012).

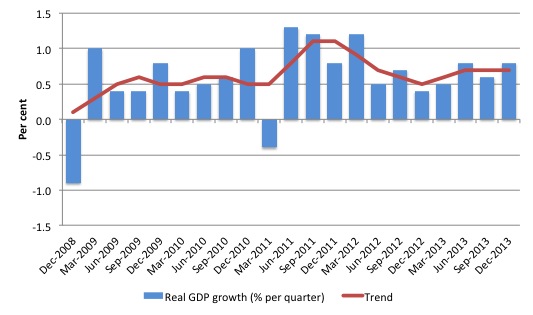

Overall growth picture – continuing to trend down

The following graph shows the quarterly percentage growth in real GDP over the last five years to the December-quarter 2013 (blue columns) and the ABS trend series (red line) superimposed. After the decline in trend growth was arrested by the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 the decline in government support saw the dip in trend growth in 2010.

Initially, the growth in private investment associated with the record terms of trade and the resulting mining boom helped drive the new rise in trend growth and that appears to have ended in the December-quarter 2011.

As private investment boom has receded and the impact of fiscal austerity bites, growth has flattened out and the Australian economy is now stuck in a stagnant below trend growth state, which is insufficient to keep unemployment from slowly rising.

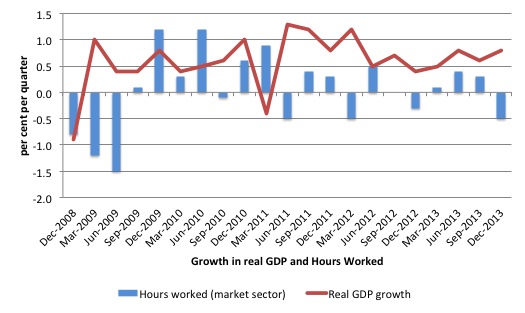

Real GDP growth and hours worked

One of the puzzles over the last several years or so has been the sharp dislocation between what is happening in the labour market and what the National Accounts data has been telling us.

Employment growth and hours worked has been virtually flat over the period while annual real GDP growth has been around 2.4 to 2.6 per cent. Today’s data suggests dislocation is continuing. Economic growth at around 2.8 per cent is still insufficient to absorb the labour force growth and productivity growth, especially as the latter being above recent trends. The two facts help to explain why employment growth has been unusually flat over the last 24 months.

It is true that employment growth tends to be a lagging indicator as firms make adjustments to hours first when contemplating increasing labour inputs. But unless labour productivity falls substantially, economic growth of the current magnitude will not deliver employment dividends of any significant amount in the coming year.

The following graph presents quarterly growth rates in trend GDP and hours worked using the National Accounts data for the last five years to the December-quarter 2013.

You can see the major dislocation between the two measures that appeared in the middle of 2011 persisted throughout 2013. While hours worked increased in the middle two quarters of 2013 and were more in line with what we would expect, the divergence between real output growth and hours worked has once again widened.

Just in case you think the labour force data is suspect, the hours worked computed from that data is very similar to that computed from the National Accounts.

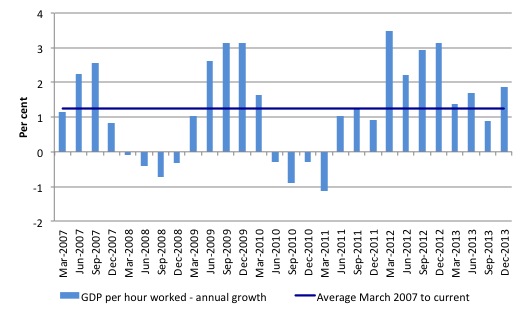

To see the above graph from a different perspective, the next graph shows the annual growth in GDP per hour worked (so a measure of labour productivity) from the March 2007 quarter to the December-quarter 2013. The horizontal blue line is the average annual growth since March 2007.

The relatively strong growth in labour productivity in 2012 and the mostly above average growth in 2013 helps explain why employment growth has been lagging given the real GDP growth. Growth in labour productivity means that for each output level less labour is required.

In the recent four quarters, labour productivity growth has slowed but remains relatively strong. However, with the investment boom now seemingly over, we should start to see real GDP growth and employment growth start to converge back to more typical proportions.

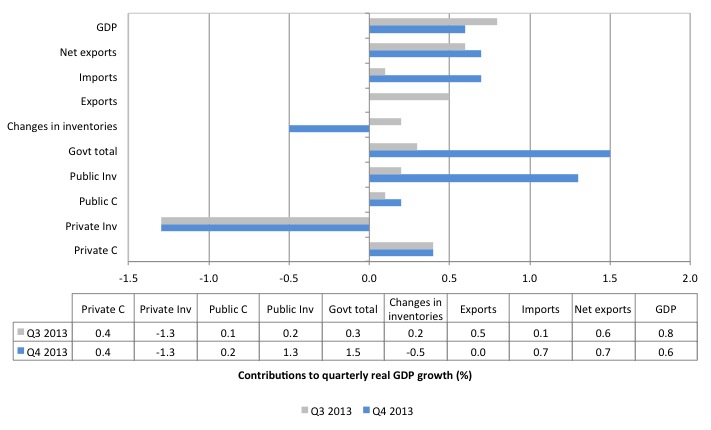

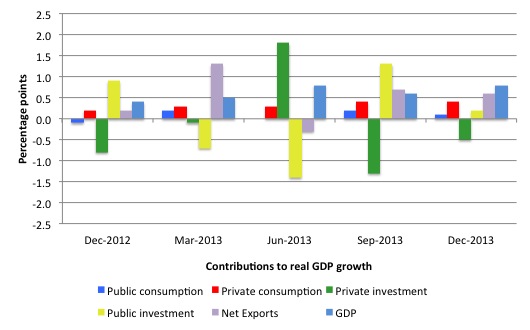

Contributions to growth

What components of expenditure added to and subtracted from real GDP growth in the December-quarter 2013?

The ABS tell us that:

In seasonally adjusted terms, the contributors to expenditure on GDP were Public gross fixed capital formation (1.3 percentage points), Net Exports (0.7 percentage points) and Final consumption expenditure (0.4 percentage points). The detractors were Private gross fixed capital formation (-1.4 percentage points) and Changes in inventories (-0.5 percentage points).

The following bar graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth (in percentage points) for the main expenditure categories. It compares the December-quarter 2013 contributions (grey bars) with the September-quarter 2013 (blue bars).

The overall contribution of investment is negative (-1.1 percentage points) given that the sharp contraction for private capital formation (-1.3 percentage points) and the more subdued growth in public investment (0.2 percentage points).

Note that the strong contribution from net exports in the December-quarter 2013 (0.6 percentage points). This is driven by a small contribution from exports (0.5 points) and a drop in imports (0.1 points), the latter the result of below-trend growth.

The contributino of Private consumption is stable.

The public sector contribution (0.3 percentage points) is down from the 1.5 percentge points in the September-quarter. But it continues the pattern of government support for growth and the reversal of the fiscal contraction which began in the September-quarter 2013. With government support over the last six months, real GDP growth would have been -0.4 percent rather than 1.4 per cent. Who ever said that fiscal policy wasn’t effective?

The next graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth of the major expenditure aggregates since December-quarter 2012 (in percentage points). The total real GDP growth (in per cent) is also included as a reference.

The stand-out result is the recent reversal in the contribution of public capital formation and the negative contribution of private investment as the boom associated with the mining sector has ended and the record terms of trade moderate.

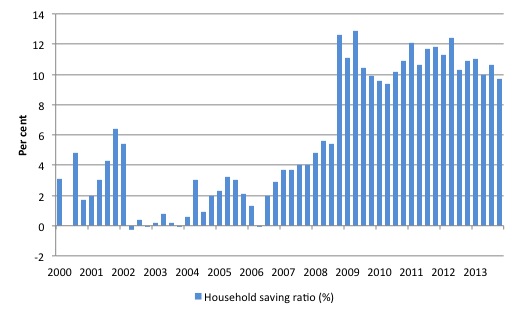

Household saving ratio drops below 10 per cent

The following graph shows the household saving ratio (% of disposable income) from 2000 to the current period. The household sector is now behaving very differently since the GFC rendered its balance sheet very precarious. Prior to the crisis, households maintained very robust spending (including housing) by accumulating record levels of debt. As the crisis hit, it was only because the central bank reduced interest rates quickly, that there were not mass bankruptcies.

The household saving ratio was 9.7 per cent of disposable household income in the December-quarter 2013, down from 10.6 per cent in the September-quarter 2013.

We will have to wait to see if households are starting to spend more and save less of their disposable income as a trend or whether the relatively strong consumption growth is being driven by the recent growth in Real net national disposable income. I suspect it is the latter.

For the economy to continue to grow strongly while households are maintaining this higher levels of saving (from disposable income), public spending, private investment and/or net exports have to increase.

Clearly, the contribution from private investment is now negative (over the last two quarters). The net exports contribution in the current quarter is strong and but insufficient to drive growth to its trend levels (around 3.25 per cent).

Which means that continued growth still requires a relatively strong contribution from the government sector.

The problem is that if incomes start to drop and the households continue to pursue this saving proportion aggregate demand will decline.

The household sector is now carrying record levels of debt as a result of the credit binge leading up to the crisis and we are unlikely to see a return to the low saving ratios that were evident in the period 2000 to 2005.

That means that government surpluses which were associated with the credit binge, and only were made possible by the unsustainable credit binge are untenable in this new (old) climate. The Government needs to learn about these macroeconomic connections.

A return to higher saving ratios is surely signalling a need for a return to more or less continuous budget deficits, depending on what happens to the external sector.

Conclusion

Today’s National Accounts data indicates that economic growth has accelerated a little but the trend pattern (a moving average of recent quarters) has converged for the time being around a below-trend growth path as the investment phase of the mining boom slows.

Remember that the National Accounts tells us what was happening in 3-6 months ago. The most recent evidence is mixed with some data showing improvement and other indicators showing the sluggish economy persists. It is hard to get a clear picture but the direction appears to be positive growth for the time being but not sufficient to put any dent into te high unemployment.

I think today’s national accounts data paints a fairly subdued overall picture for the Australian economy. Subdued without being disastrous.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill:

I think the data is much worse than you suggest. Let’s look at the positive contributions to GDP – net exports, private consumption, and public GFCF. I’ll keep insisting to the cows come home that net exports constitute a form of foreign aid – a nation using its own scarce resources to give up, in a net sense, more useful stuff to foreigners than it receives in return (and only because the Fed Govt isn’t sufficiently net spending). Secondly, it’s clear from what you show that private consumption is being increasingly financed by credit rather than income, which we know helped to trigger the previous collapse in consumption spending (and the previous financial crisis). Finally, we have a new Fed Govt that is hellbent on running the budget back to surplus (even though it was almost certainly fail). Hence we can expect the contribution of public GFCF to start falling. At the same time, private sector GFCF is already declining.

Overall, it seems the only way a rise in the unemployment rate will be prevented under this new Govt is by having Australian households run down their meagre savings and Australia increasing its trade-related foreign aid, as I prefer to call it. One of these will increase the financial fragility of the Australian economy; the other will make us worse off (no benefits yet a cost in terms of the value of what is surrendered, which is now likely to be more of Australia’s old growth forests given the nature of the unsubstantiated statement from the PM overnight).

Typo – 4th sentence

“With the contribution of the government sector growth would have been negative over the last two quarters. “

Phil, what alternative would you suggest?

Rich people are not spending their money on extreme luxuries, so poor people can’t get jobs providing them those luxuries. They don’t want that level of luxury, they want investment opportunitites which they can’t get because demand is so low. So they sit on their money, they buy government bonds and get a trickle of interest, or they invest in some other nation.

The government can’t spend a lot to buy things that poor people could get jobs making. If they do they’ll have to put out more bonds and pay interest on them forever. What good is that? There’s no way they can just print the money, they have to borrow it and give somebody a permanent income….

And we don’t want people to spend down their savings or go deeper in debt.

The only way to get jobs are to work for foreigners doing what foreigners want. Nobody else can afford it.

Sure, it would be better if Australians did a lot of work and kept the wealth they created in Australia. Then Australia would be richer. LIke, say you mine iron and coal and make steel, you make stuff from the steel and use it. People share in the wealth they create.

But you can’t do that. Nobody in australia who wants that can afford it. So instead you mine coal and export it, and you mine iron and you export it, and you make steel and you export it. Because China can pay for it, and you can’t.

That’s just economic reality. Australia is poor so you must work hard and ship things to China and not get much back. It’s the iron laws of economics.

If there was a war and trade was disrupted, Australia would ignore the Iron Laws of Economics. You would make your steel and create warships and tanks, drones and missiles. If there was any chance that China would invade you would do whatever it took to stop them. Everybody would pitch in and assist the war effort. But luckily there is no war. So you have no choice but to give foreign aid to China in exchange for their electronic money, or else have massive unemployment.

It’s all very sad.

J. Thomas, I can only assume you are using irony (pun intended). “If there was a war and trade was disrupted, Australia would ignore the Iron Laws of Economics.” Of course, if you can ignore “Iron Laws” then they aren’t iron, indeed they aren’t even Laws. This is the point of course. There is no iron law that says we have to send all our iron (and coal) to China. We could indeed re-start a national steelworks (or two or three) and start building much needed infratrsucture; rail, bridges, urban renewal, wind farms and solar power stations. Heck, we could even start building useful ships instead of submarines that don’t work. And why not start an electric car industry since we have finally got rid of that filthy oil burning IC engine car industry? People might say it’s an economic waste if we can’t do it most efficiently (e.g. make electric cars or ships). However, we should look at the real and biggest waste of all.

The biggest waste is not employing people. The last statistics I saw indicated the cost of raising a child to 18 or to 24 could range from $400,000 to $1,000,000 depending on the family and what they provided. So every young person we throw on the scrapheap is about $700,000 thrown away, to take an average. Would any business throw away $700,000 machines without using them? Well, why does Australia, as a national business, throw humans away? Humans are the most complex and adaptive value adding machines on the planet. They have needs and feelings too which is another argument why they should be usefully employed and rewarded.

“J. Thomas, I can only assume you are using irony (pun intended).”

Yes, very much so!

“Would any business throw away $700,000 machines without using them?”

Yes. If a business has a $700,000 machine that it cannot run at a profit, it must mothball it or sell it. It’s illegal for Australia to sell its unemployed, but some of them could perhaps go be guest workers in other nations.

Australia may be facing a problem of lack of demand.

Consumers can’t spend much more, they’re already going into debt and after awhile they won’t be allowed to borrow more.

Government does not want to go deeper in debt.

Businesses may invest so they can produce more, but who will buy more? Only foreigners.

In ancient days Keynsians believed that government should go as deeply in debt as necessary to boost demand. But that is considered unacceptable now.

At first sight there is no possible solution.

To increase demand you must somehow change the rules of the game. Somehow you must change the Iron Laws of Economics. Just possibly MMT will tell you how to do that and make it work.

The old laws say “We must not produce any more than the people who have money will pay for.”.

But the people who have money don’t want to pay for more stuff. They want to pay for investments that will make them more money. Except they can’t squeeze more money out of employees. People who work for a living already spend all they get and more. And they can’t get more money from the government unless they lend it the money first.

So by those rules we must cut back production until it makes what the owners want plus what their employees can pay for with their wages, plus a little something for the people on the dole. Plus exports. Cut back production that far and then wait for something to happen.

Can we find other rules that will work better? If so, will powerful people allow us to try them?

Rule #1: Idle capital shall be redistributed.

Robert, it makes sense to me that other things equal we should arrange things so we can be productive and then enjoy the results of our productivity. And idle capital does not do that.

But I’ve noticed that people believe there are other rights which might conflict with that. For example, they believe that people should be able to save their money for retirement.

Say I have enough money to build a swimming pool in my back yard. But instead I do without, and I save the money. I put it in long-term bonds or something. Then when I retire the economy owes me a swimming pool or stuff of equal value.

The government owes it to me to arrange things so I can save all the money I want to and then spend it later whenever I want and not lose on the deal.

I don’t think that necessarily has to work out, but people believe the government owes it to them to make it work out.

So, what if on average people choose to save too much? I think that might be happening in Japan. People want to save, they don’t want to spend too much. At first they invested in lots of stuff, they made steelworks and shipyards and electronics plants and every investment they could put money into. But then they found that there wasn’t enough demand for all the stuff they could make. They had to sell at too low a price to pay off the investment. So with their savings not paying off they try to save more and consume less, and they are stuck.

It’s bad to have idle capital when demand is too weak. But if you take away people’s savings from them and give the savings to people who’ll just spend them, the people you take the savings away from will get pretty irate about it. They were raised to think that by being stingy and reducing their expenses and saving their money they were doing the right thing. If you steal their hard-earned wealth, their little scrap of security, they will hate you.

We need some way to deal with that.

Apart from hoarding behavior, people may choose to save money as protection against an uncertain future. In our economy, that would equate to a loss of income. They may also wish to retire early.

A job or income guarantee would help alleviate these concerns. It would not eliminate them. I doubt that even an extensive social safety net would convince everyone that their lives were no longer in a precarious state.

Redistribution (or reallocation) of capital could be accomplished through progressive taxation, or expropriation. This would tend to affect the wealthy more than those with modest means.

If an expiry date were added to income, everyone would be forced to exchange it for something of immediate or longer term value. If money were designed to function only as a medium of exchange, then people seeking long term security would have to look elsewhere. If they choose to invest in stock, or buy precious metals, then those things would serve as their store of wealth.

Robert, everything you say sounds reasonable to me. However I’m sure it would all be politically controversial.

An income guarantee? Cradle-to-grave nanny state? People forced to depend on the government and prevented from taking care of themselves? Tax the rich?

I like the idea of money with an expiration date, but as it gets close to that date won’t it depreciate? Kind of like a game of hot potato or hand grenade, you don’t want to be holding it when it goes off. If it’s going to depreciate anyway, instead of letting it expire you could have it constantly depreciate. It gets worth less the longer you hold it.

Say you did that for the dole. Everybody on the dole gets a debit card. Every month the government loads it with money, and every day they take back a fraction of what’s left. If you don’t spend it by the end of the month it’s gone anyway. Money that can be spent but cannot be saved. It probably wouldn’t be very controversial to do that to people who’re on the dole, it would look like a punishment, and it would be a start toward spreading the idea further.

The expiry date is for the person or firm that received the income. It doesn’t depreciate, it just has to be spent. If it isn’t, the exchange offered to acquire it would be considered a gift. Nowadays this form of money would be electronic.

Money with an expiry date is an old idea, and was mentioned by Marx in one of his letters. These labour vouchers were intended to be used by the individual that earned them. When they were exchanged for a good or service, they would be extinguished. They could not be accumulated by another party.

What I’m describing is a) a method to separate savings from the medium of exchange, and b) redistribution of capital to encourage economic activity. We can’t allow the accumulation of wealth to bring the economy to a close, as if it were a game of Monopoly.

I don’t understand the opposition to the nanny state. There are increasing numbers of people who do not participate in the labour force. A few of these are known as the idle rich. The vast majority however, receive insufficient earned income. I can see three general approaches to dealing with the unemployed: employ them, support them, or kill them. Current policy is to support them, both formally (the dole) and informally (charity, family). A JG or BIG is merely a continuation of the social safety net.

If we insist upon profitable ventures as the only source of employment, unemployment will be the result. Trends in automation and productivity will tend to reduce the amount of labour required, and reduce the amount of income that workers will be able to earn. This then erodes the consumer base needed to purchase the goods and services being offered, i.e. aggregate demand. A vicious circle.

In theory, there is an infinite amount of work (or play) that can be done if we ignore the profit/efficiency criterion. The practical limit is energy availability.

Is it politically controversial to keep people alive and allow them some dignity?

“What I’m describing is a) a method to separate savings from the medium of exchange, and b) redistribution of capital to encourage economic activity. We can’t allow the accumulation of wealth to bring the economy to a close, as if it were a game of Monopoly.”

I approve. I think we need to look very carefully at methods to do that. Some methods might be better than others, and if we choose a worse one it may be as hard to switch as it will be to get the first one established. Maybe harder — if the first approach has flaws a lot of people will say it proves the idea is wrong and we should try unregulated free markets.

“If we insist upon profitable ventures as the only source of employment, unemployment will be the result. Trends in automation and productivity will tend to reduce the amount of labour required, and reduce the amount of income that workers will be able to earn. This then erodes the consumer base needed to purchase the goods and services being offered, i.e. aggregate demand. A vicious circle.”

Yes. Agreed.

In the USA however we have an ideology which appears to be growing, which says that free markets are never wrong. They want to say that anything bad which happens, happens because of government. If an unregulated free market does it then it must be the best panglossian result that could happen.

It’s a sort of Calvinist belief. If you are worthy, the economy will reward you. The economy exists to reward the worthy, and if you do not make much money it’s because you aren’t worth much. In a free market everybody always gets what they deserve.

Usually they say that private charity would provide for whever can’t provide for himself. They don’t take it to the logical conclusion that by the Iron Law of Supply and Demand, if the supply of labor is above demand then the price of labor will decline until starvation reduces supply to meet demand. It does follow naturally from the argument, though. People who are in low demand exist to provide rewards for the worthy that the economy rewards. They don’t have rights or dignity for themselves.

I’d like to think that this sort of thing will decline, but I meet a surprising number of relatively poor people who are ready to say that they deserve what they can get from the free market, and nothing more.

I’d like to think that this sort of thing will decline, but I meet a surprising number of relatively poor people who are ready to say that they deserve what they can get from the free market, and nothing more.

If they can get a roof over their head and enough to eat, why not say it?

Do they retain their self-esteem?

Another rationale for this comes from having the onus to succeed placed on the individual.