At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 19

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[PRIOR MATERIAL HERE FOR CHAPTER 1]

Next stop – “L’Europe se fera par la monnaie ou ne se fera pas” – the European Monetary System (EMS)

In 1950, Jacques Rueff, who was a trusted economic advisor to Charles De Gaulle and French central banker wrote that “L’Europe se fera par la monnaie ou ne se fera pas” (“Europe will be made by money or it won’t be made”), which provided the mantra for those who believed that the ‘European Project’ ultimately would require a single currency (Rueff, 1950).

As the ‘snake’ was falling apart, the President of the Commission of European Communities, Roy Jenkins delivered the first Jean Monnet lecture in Florence on October 27, 1977. Jenkins (1977: 3) described the demise of the Werner plan as a “retreat rather than an advance”. In making the case for a renewed push to monetary union he said (1977: 5) that there would be advantages in “creating a major new international currency baçked by the economic spread and strength of the Community, which would be comparable to that of the United States, were it not for our monetary divisions and differences”. He claimed that eliminating the currency fluctuations within Europe would improve economic welfare. Rueff’s agenda was very much back on track.

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

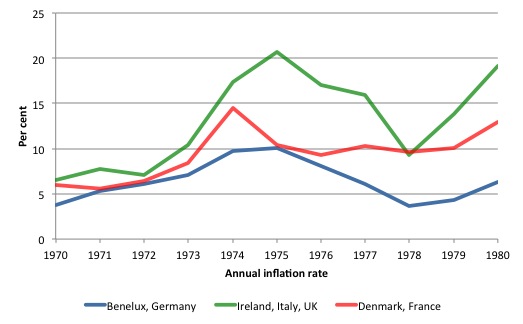

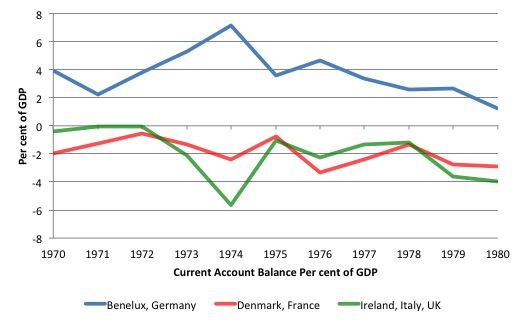

The economic situation across the ‘snake’ membership was disparate. The withdrawal of the French Franc in March 1976 captured the problem facing the non-German membership – either they had to continually devalue their currencies or create high unemployment in their domestic economies to reduce imports. Neither option was politically tenable. Even after the revaluation of the Deutsche Mark in October 1976, the remaining currencies were under pressure. Figure 1.2 shows the average annual inflation rates between 1970 and 1980 of the low-inflation nations (Benelux, Germany), the mid-inflation nations (Denmark and France), and the high-inflation nations (Ireland, Italy and the United Kingdom) while Figure 1.3 shows the respective current account balances as a percent of GDP.

The low-inflation nations also had strong trade positions and were facing upward pressure on their currencies, particularly Germany. The rest of the nations were running weak trade positions and faced the opposite pressures on foreign exchange markets. These disparities made it virtually impossible for the fixed parities embedded in the ‘snake’ arrangement to be maintained.

Figure 1.2 Comparative inflation rates among original ‘snake’ membership, 1970-80, per cent per annum

Source: European Commission, Annual macro-economic database.

Figure 1.3 Comparative Current Account Balances among original ‘snake’ membership, 1970-80, per cent of GDP

Source: European Commission, Annual macro-economic database.

Further, the CAP was causing further tensions, particularly in France. The CAP became more complicated in 1969 when the Deutsche Mark was revalued and the French Franc devalued. The CAP required that the EC harmonise agricultural prices expressed in terms of a common “Agricultural Unit of Account” (AUA), which was set in terms of gold parity of the US dollar as used in the Bretton Woods system and introduced in 1962. So one AUA corresponded to one US dollar. In turn, these common CAP prices were converted into national currencies using the exchange rate parities. Stability of the fixed agricultural price system across the membership thus depended on the stability of national currencies because if one currency depreciated, the fixed prices would yield a competitive advantage to that nation’s farmers and vice versa.

A relatively simple solution would have been to simply adjust the national currency price upwards for devaluing nations and downwards for revaluing nations. In the former instance, the French argued that “such a sharp rise would not have been desirable either internally, where it would have aggravated the inflationary trends which had given rise to the devaluations and would have put the farmers concerned in a more privileged position than other social and professional categories, or in the European context, where it would have provoked over-production of certain agricultural products” (EC, 1974: 6). In the latter case, the strength of the farm lobby in Germany was such that cutting farm incomes would not have been politically possible. The system was already pitched in Germany’s favour. The less efficient farming nations such as Italy and Germany wanted the system of harmonised prices to be higher than otherwise. The French, who had a more efficient agricultural sector, were concerned that artificially pushing up agricultural prices would be inflationary. The less efficient farming nations won the day.

To cope with the 1969 realignment in the French and German currencies, the EC introduced a complex system of so-called ‘green exchange rates’ or simply ‘green rates’. These rates were designed to insulate farm prices from the fluctuations in market exchange rate fluctuations. They were set at the parities that ruled prior to the realignment. Without them, farmers in say Germany, would experience a drop in farm income, because a given AUA price would translate into less Deutsche Marks, after the Mark was revalued. By expressing the AUA in terms of the ‘green rates’, farm incomes were stable against currency fluctuations. If the national currencies were stable against each other, then the ‘green rates’ would be equal to the actual exchange rates. Once the ‘green rates’ were introduced the “EU effectively abandoned common agricultural prices” (von Cramen-Taubadel and Thiel, 1994: 263). There were also equity issues involved. In the case of a revalued Deutsche Mark, while the German farmers received the same Mark payment for their farm output, their Deutsche Mark-income was now more valuable against all other currencies. There was resentment in the other nations about this inequity in the system.

The ‘green rates’ were then accompanied by the system of Monetary Compensatory Amounts (MCAs) which were introduced “to correct any distortions in competition that might emerge between the EEC Member States as a result of fluctuations in exchange rate parities” (CVCE, 2013x: 2). The system involved levies being imposed on intra-EU farm exports that had become more competitive after a devaluation and subsidies paid to intra-EU farm exports that has been damaged as a result of revaluation. The impact of both was to protect farmers “especially in strong currency countries that would otherwise have suffered from revaluation-induced CAP price reductions” (von Cramen-Taubadel and Thiel, 1994: 263). After France left the ‘snake’ in 1976, the French farmers lobbied to have the MCAs terminated, given the implications of the system for their overall farm incomes in the context of a weakening French Franc.

Carchedi (2001: 205) considered the MCAs to be “a flagrant violation of the EEC principles” (which prohibited any duties being imposed on trade within the common market) and “both reflected and fostered from the very beginning the interests of Germany, that is, of the German conservative ruling classes”. Such was the complexity and opaqueness of the system, that Eichengreen writes (2007: 184) of “the German chancellor emerging from a meeting of the Council complaining that he had only one official who understood the system of green exchange rates but could not explain it, and one official who could explain it but did not understand it”.

Within this context, big changes were also underway in French politics, which significantly altered economic policy, not only domestically, but also with respect to the ‘European Project’. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was elected as President in 1974. In the traditional struggle between the French policy makers in the Planning Ministry (under Jean Monnet) and the technocrats in the Ministry of Finance (who were more amenable to the German position on integration and economic management), Giscard d’Estaing was in the latter camp.

Canadian philosopher and writer, John Ralston Saul, examined the role played by Giscard d’Estang in France during the 1970s in his 2005 book ‘The Collapse of Globalism and the Reinvention of the World’. In an interview with The Guardian, Saul told Stuart Jeffries (2005) that Giscard d’Estang “first verbalised the idea that economics was the prism through which we should see civilisation” at the initial G7 meeting in 1975. Saul also said that the French politician “believed free markets would establish natural international balances” and that “Boom and bust was over”

Initially, he had to share power with the Gaullist Prime Minister Jacques Chirac as part of a reconciliation strategy to resolve internal conflicts in the parliamentary majority. However, this proved untenable and Chirac quit in 1976 in order to rebuild the Gaullist power base in French politics and position himself for a tilt at the Presidency in the next election.

When Giscard d’Estaing appointed Raymond Barre as Chirac’s successor as Prime Minister, he proclaimed him to be the “meilleur économiste de France” (best economist in France). The pair promoted a powerful anti-Gaullist position with respect to both domestic economic policy, reflecting their neo-liberal views, and moved the French perspective on ‘Europe’ closer towards the German ‘economists’ viewpoint.

Barre also took on the role of Minister of Economy and Finance and set about implementing the so-called 1976 ‘Plan Barre’, which involved a combination of wage freezes to fight inflation, fiscal austerity, attacks on trade unions and industrial restructuring, particularly in the steel industry.

[END OF NEW AND PARTIALLY REWRITTEN MATERIAL TODAY]

On December 5, 1978, the European Council met in Brussels and agreed to set up the European Monetary System (EMS), which was to absorb what remained of the ‘snake’ and establish a European Currency Unit (ECU) (European Council, 1978). The EMS emerged out of a proposal put to the European Council meeting in Copenhagen in April 1978 by the French President Valery Giscard d’Estang and the German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt.

It won’t surprise the reader to learn that the system eventually found itself in crisis and instead of abandoning the almost impossible idea of tying these disparate European economies together into a functioning fixed-exchange rate currency zone, the European political leaders began the rocky road to Maastricht with a compromised EMS and the creation of the Delors Committee. But first, we have to tell the story.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

[WE ARE MOVING TOWARDS THE DELORS REPORT IN THE LATE 1980s AND THE TREATY OF MAASTRICHT – THINGS WILL FLOW MORE QUICKLY AFTER THAT – I HOPE!]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Carchedi, G. (2001) For Another Europe: A Class Analysis of European Economic Integration, London, Verso.

CVCE (2013) ‘Ten years of monetary compensatory amounts’, from Le Monde (8 March 1979)’, Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l’Europe.

Eichengreen, B. (2007) The European Economy Since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

European Commission (1974) ‘Compensatory Monetary Amounts, The Monetary Crisis and Common Agricultural Policy’, Common Agricultural Policy Digests, No. 25-26, April-May 1974, European Commission and Ministry of Agricultre and Rural Development, France. http://aei.pitt.edu/5544/1/5544.pdf

Hofreither, M.F. (2009) ‘Origins and development of the Common Agricultural Policy’, in Gehler, M. (ed.) From Common Market to European Union Building. 50 years of the Rome Treaties 1957-2007, Böhlau, Vienna, 333-348.

Rieger, E, (1996) ‘The Common Agricultural Policy: External and internal dimensions’, in Wallace, H. and Wallace, W. (eds.) Policy-Making in the European Union, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 97-123.

von Cramen-Taubadel, S. and Thiel. H. (1994) ‘EU Agriculture: Reduced Protection from Exchange Rate Instability’, Intereconomics, November/December, 263-268.

I wonder whether it might be useful to collapse Figures 1.2 and 1.3 into a single figure

which plots inflation versus CA deficit. Assuming that the year to year variations are

not a major component of the teaching agenda, displaying the correlation of the

two variables would communicate to the reader without need to move the eye

between the two figures.