I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

The British agenda to bring workers to their knees is well advanced

In Australia, 84 per cent of jobs created in the last 6 months have been part-time and underemployment has risen since February 2008 (the low-point in the last cycle) from 666.3 thousand (5.9 per cent) to 908.6 thousand (7.4 per cent). And this is a period that the spin doctors in government and the media told us was our once-in-a-hundred year mining boom bringing rich bountiful futures to all. The only problem is that the future workers (our 15-19 year olds) have endured an absolute contraction in employment in the 5 years since early 2008. The Government hasn’t embraced the full-on austerity that is failing Britain but has still overseen a contraction in fiscal policy which is now damaging growth and creating an increasing pool of low-paid, insecure jobs as full-time employment vanishes. In Britain, the situation is even more dire with a Government hell-bent undermining the prosperity of it citizens. The British Trades Union Congress (TUC) released an interesting report last week (July 12, 2013) – The UK’s Low Pay Recovery – which shows that “eighty per cent of net job creation since June 2010 has taken place in industries where the average wage is less than £7.95 an hour”. The British Chancellor is looking increasingly cocky lately declaring that Britain is “out of intensive care”. From the data I examine most days, nothing could be further from the truth.

The BBC reported that George Osborne considers the British economy is moving from “rescue to recovery” and that the economic plan has helped the nation “turn the corner” and the economy is “out of intensive care”.

You can see the BBC video interview with George Osborne (June 23, 2013) – Spending review: Defence jobs cut as Osborne reaches deal – where he declares that further public sector job cuts will be made.

He admits that the target reductions in the budget deficit and debt have not been forthcoming as yet. Which gives you a clue as to why the British economy is not collapsing like the Greek economy.

The deficit is still probably large enough to support some growth (if that is what this week’s National Account’s estimates reveal). The deficit is clearly not large enough to ensure a high level of economic growth which would eat into the unemployment pool.

So the result is that the British economy is limping along, waiting for the really harsh austerity cuts to start binding. Several things accompany such a state.

First, potential output starts to decline due to a stagnant private investment climate and a decline in public capital formation (as a result of choosing easy targets to engage the austerity drive).

However, the British Treasury didn’t wait for the stagnation to undermine the future growth path. Their estimates of potential output in Britain were significantly reduced soon after the crisis began, and that dramatically altered the way the Treasury and the politicians discussed the state of fiscal policy.

In the – Pre-Budget Report 2008 – published by the British Treasury we read (P. 162):

For the 2008 Pre-Budget Report, to take account of the likely negative effect of the credit shock on trend output, a phased reduction to the trend level of productivity (and therefore the trend level of output) of about 4 per cent has been assumed over the two years from mid-2007, a period consistent with the credit conditions assumption that underpins the economic forecast more generally.

That means that the estimate of potential output (they use the term “trend output”) was reduced by 4 per cent in a matter of months (between the March 2008 Budget presentation and the November 2008 Pre-Budget Report). The implications of that was clear – the estimated decomposition of the budget balance allowed the Treasury to convert what was previously a cyclical budget deficit (as a result of the slow-down in economic activity into a structural budget deficit.

They claimed that the “cyclical indicators suggest the economy remained above trend during 2007 before falling back towards trend during the first half of 2008”.

So despite the economy falling into a hole, the rise in the deficit was considered to be structural – with no cyclical elements after the first half of 2008

This sort of creative accounting then provided the base for the politicians to claim that the deficit was due to overspending by government and the austerity narrative began.

The estimates of potential output have been reduced by a number of studies since. In Chapter 1 of the Green Budget (February 2010) published by the Institute of Fiscal Studies – The UK’s productive capacity: surveying the damage – we read that:

We find that severe crises, such as that which the UK is currently suffering, tend to reduce the level of potential GDP by around 71⁄2%, with most of the decline being felt by the fifth year … [overall] … we go with a larger deterioration of 10% … Our best estimate is more pessimistic, being that the level of potential GDP will be reduced by 71⁄2% over three years and that thereafter it will grow by only 13⁄4% per year

That is the dilemma that the decline in potential output – which is now the result of persistent stagnation – undermines the future prospects for non-inflationary growth and locks in the high unemployment rate.

While the neo-liberals will claim the NAIRU (the rate of unemployment consistent with stable inflation) has risen due to structural factors such as excessively generous welfare benefits, overly protective employment protections and other regulations designed to improve the lot of the workers, the reality is that the inflation constraint binds earlier because of the entrenched output gap and the resulting sluggish investment profile.

That shifts the unemployment into what Malinvaud (the French macroeconomist) called capacity-constrained unemployment. It is still the result of deficient aggregate demand but suggests that a solution has to lie in the growth of productive infrastructure – both private and public.

So if the UK government was sensible enough to entertain the obvious – the need for fiscal stimulus – then it would be advised to invest heavily in areas that will crowd-in private investment spending (once the private sector was confident enough to start investing again).

Large-scale public investment particularly in green technology, education, health etc all would have this virtuous impact. But once a nation finds the size of its potential output contracting it is reaping the second-wave of negative effects of a major downturn.

As the estimates show, the really significant declines in potential output start occurring after about 5 years. Britain is at that point now and the costs of driving further austerity will start to accelerate from this point onwards.

Further, the claims that employment growth in Britain is a sign that the austerity is not having a significant impact are refuted by the findings of the TUC’s The UK’s Low Pay Recovery Report.

The Report finds that:

… of a 598,000 net rise in employee jobs across high and low paid sectors since June 2010, 77 per cent are in low-paid industries, such as retail, waitressing and residential care.

A low-paid job is one where “the average hourly wage is £7.95 or lower (the 25th percentile of average hourly earnings)”.

The Report finds that:

Retail has made the biggest contribution to rising employment levels, with the number of employee jobs in this sector increasing by 234,000. The average wage in retail is just £7.35 an hour. Residential care, where the average wage is £7.78 per hour, makes the second biggest contribution of 155,000 jobs.

Just over one in five (23 per cent) net new employee jobs created since June 2010 has been in the highly paid computer programming, consultancy and related services industry, where the average hourly wage is £18.40. The workforce in this sector has grown by 131,000.

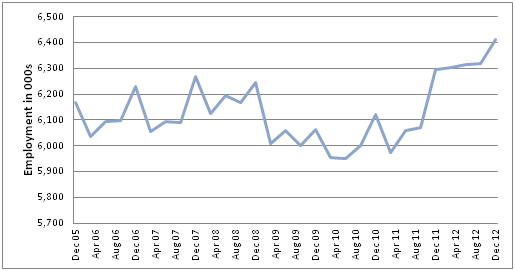

The related TUC Blog – – produced this graph showing total low-paid jobs between December 2005 and December 2012.

So there are two trends revealing themselves in Britain. Not only did the low-paid industries endure the “the sharpest jobs decline during the recession” but the recovery has been dominated with growth in low-paid employment.

The middle-paid industries lost a significant number of jobs and there has been no recovery since. Further, the higher-paid industries “never really felt the impact of the recession”.

So the recession destroyed the middle-paid jobs and the persistent downturn has allowed firms to restructure these jobs into lower-paid, more precarious positions. The implications for future productivity growth (and therefore growth in living standards) is obvious.

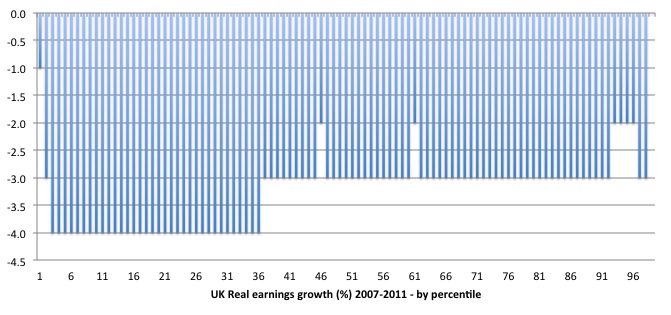

Further, real earnings growth between 2007 and 2011 has disadvantaged the lower percentiles in the wage distribution with the top percentile not losing at all.

The following graph (using the British Office of National Statistics dataset – Earnings in the UK over the past 25 years, 2012) shows real earnings growth in the UK between 2007 and 2011 by percentile of the wage distribution.

The 1 per cent (at the top) were the only percentile to suffer no real earnings loss. You can also see that the losses are concentrated in the lowest 36 percentiles (excluding the lowest 1 and 2 percentiles).

The evidence is more damming however. More than 50 per cent of the jobs created in Britain since 2011 have been for self-employed workers where the wages are even lower than indicated above.

The UK Guardian article (July 16, 2013) – George Osborne: this economic recovery SUCs – says that:

And since 2011, half of all new jobs have come from people going self-employed, where median wages are even lower: under £6 an hour. Far from a Britain of startups and entrepreneurs, Osborne has created what City economist Dhaval Joshi refers to as “an army of underpaid freelancers”.

The neo-liberals will undoubtedly applaud the rise of the entrepreneur – the small-scale business person. But the reality is that a huge number of British workers who were previously in relatively skilled positions are now eking out a survival strategy in low-skill, casual work in the retail and services sector.

The TUC spokesperson noted that:

Many people who are forced into low-paid work are not only having to take a massive financial hit, but are also having to put their careers on hold. This trading down of jobs can also push those with lower skills and less experience, particularly young people, out of work altogether. This is tough for workers and damaging for the wider economy.

This is one of the reasons why governments should do everything to prevent a major recession from enduring. The long-term damage to potential output growth is high and the personal costs to the people involved catastrophic.

Conclusion

While the neo-liberals will seize on any signs of growth to argue that fiscal austerity is a positive force and use all sorts of aggregate statistics to justify their claims the reality lying beneath the aggregates is quite different.

The same trends happened in Australia during the very deep 1991 recession. Prior to that recession, underemployment was very low. During that recession, full-time work fell alarmingly and firms converted their job structure increasingly towards part-time work. Underemployment jumped during that recession (as did unemployment) but the trend was set – the subsequent recovery not only took a long time to reduce the unemployment that was generated but also underemployment persisted at the new higher levels.

Increasingly, the Australian economy produced low-paid, precarious positions which undermined growth in real standards of living. The same outcome is looking obvious in Britain. So the legacy of the crisis will not only be the losses of national income that occur because of the huge output gaps that have arisen (despite the creative attempts to massage the estimated output gaps downwards).

But once the crisis period is over the British workers will also find their circumstances will be considerably lessened by the trends that are emerging at present.

The neo-liberals will rejoice – real wages growth will be lower and employers will hold the upper hand. The reserve army of the unemployed will eventually be lower but it will be replaced by a huge pool of low-paid underemployed workers. The on-going agenda to reduce the capacity of workers to engage in real income growth will be further advanced.

The conclusion of the Guardian article cited above is sound:

If this is a recovery, it’s a recovery that SUCs. The S in that acronym stands for sluggish. The U for underemployed, where, as research has shown, half a million people want extra work as their wages aren’t covering their outgoings. And the C is for credit, since households with falling real wages are relying on cheap credit carrying on for ever.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What’s the thoughts on the UK’s ‘productivity puzzle’?

Again I imagine its much worse in Ireland although the pay per hour is higher.

A typical example is my niece who works 4 hours a day in a clothes shop.

She works 4 hours a day rather then 8 ~ because the shop cannot afford to pay lunch break money.

She works most days in what is turning out to be the hottest summer in Ireland since 1995.

Instead of working for 3 days a week and hitting the beech and enjoying herself she is tied to a very shitty job in nightmare consumer mall land burning petrol 6 days a week to get to a non event of a job.

You are only 19 once in life.

I am afraid there is no second chance on that stuff.

This is much more then a economic war – its a spiritual attack on peoples illusion of independence & dignity.

I imagine the guys on top of the food chain get most of their kicks from such total money / energy & subsequent total political power.

Burning young people up just because they can.

What’s the thoughts on the UK’s inflation puzzle? If there is an output gap, why is CPI so high? Are we importing it? http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_317813.pdf .

Its a strange world out there but SWilliamism somehow manages to capture the essence of it.

The Summer Banquet of the Woolmen…………

Starts proper at 8.00

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvDV62s86Z0&list=UUldfvyaPuBSpw8iDmUgZwnA

Bill never really asks the simple question , Why ?

Why do they tolerate & even seem to enjoy systems with little money to pay debt contracts ?

I don’t think its about the money.

Its about the power baby.

Acorn,

Read the BoE inflation report – http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/inflationreport/2013/ir13may4.pdf

It’s more illuminating than the ONS release.

you are spot on dork of cork

in economics as in everything

choice is an exercise in power not freedom

in markets the illusion of freedom is glaring

as markets bind people the very opposite of free

but those with power can choose to spend the money

“The neo-liberals will undoubtedly applaud the rise of the entrepreneur – the small-scale business person.”

Yes, and a lot of the increase in self employment is basically book keeping. Previously employed workers get bought off with a small pay rise or lump sum in order to turn them into self employed workers who are cheaper to deal with in the long term. They are still de facto employees, still at the mercy of their bosses. Little changes in their working practices, only their legal status is reordered.

@Kevin

The problem for people with the remaining (large) claims is that the neo – liberal society destroys the capital base on a epic scale and slowly works up the food chain.

Contrary to popular belief there is a major youth job programme in extreme neo liberal fiefdoms of the British isles.

It involves the mass hiring of salesmen for privatized utilities. (my nephew has just got a good paying “job” by todays standards in one of these sick outfits)

But their jobs is a utterly pointless duplication of activities which means the job has a negative net contribution to society but hell who cares once the rate of profit can be maintained , right ?

The simple fact of the matter is that the lower rate of unemployment in the British Isles involves people wasting time on exercises which are at best pointless , at worst taking advantage of senile old people so as to game the wealth claims out of their hands.

But young people are forced into these dead ends as they have no choice as the monetary system creates the in built morality within a society.

The UK and more so Ireland is becoming one gigantic toll booth economy where very little time and energy remains for real physical work.

They have created a giant entropy engine ……or perhaps a more accurate visual – a series of hamster wheels stretching beyond the horizon.

Thanks Nick for BoE link. Does not read like an economy moving from “rescue to recovery” and being “out of intensive care”. Acorn.

If you look at the BoE’s CPI inflation projections from the present to the first half of 2016 based on certain market factors, Numerical Parameters of Inflation Report Probability Distributions of May 2013, in the report, you see that the mode, median, and mean for the sequence of distributions are identical. This can only be if the distribution is Gaussian. I do not see any justification for such an assumption. For one thing, it means that their calculations of uncertainty will most likely be too low and, thus, their projections much too ‘optimistic’.

Addendum:

I should perhaps have mentioned that the Bank does acknowledge that they are aware of the difficulty of calculating very low event probabilities. This, however, does not detract from the point I made above.