It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Labour market measurement – Part 1

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text by the end of this year. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Chapter 10 The Labour Market

Sections 10.1 and 10.2 were sketched in this blog – The labour market is not like the market for bananas.

10.3 Measurement

While up until now we have been concerned with developing an theoretical framework to explain how real GDP and national income is determined, macroeconomics is also concerned with understanding the dynamics of employment and, relatedly, unemployment.

Many a textbook will say that “Macroeconomics is the study of the behaviour of employment, output and inflation”. Further, a central idea in economics whether it be microeconomics or macroeconomics is efficiency – getting the best out of what you have available. The concept is extremely loaded and is the focus of many disputes – some more arcane than others.

At the macroeconomic level, the “efficiency frontier” is normally summarised in terms of full employment, which has long been a central focus of economic theory, notwithstanding the disputes that have emerged about what we mean by the term.

However, most economists would agree that an economy cannot be efficient if it is not using the resources available to it to the limit. In recent decades, the emergence of issues relating to climate change have focused our attention on what that limit actually is. In this Chapter, we focus on the use of labour resources.

The concern about full employment was embodied in the policy frameworks and definitions of major institutions in most nations at the end of the Second World War. The challenge for each nation was how to turn its war-time economy, which had high rates of employment as a result of the prosecution of the war effort, into a peace-time economy, without sacrificing the high rates of labour utilisation.

In this section, we consider issues relating to measurement. How do we know how much employment there is at any point in time? What is unemployment? Is it a measure of wasted labour resources or are there other considerations that should be taken into account?

Labour Force Framework

The Labour Force Framework constitutes a set of definitions and conventions that allow the national statisticians to collect data and produce statistics about the labour market. These statistics include employment, unemployment, economic inactivity, underemployment, which can be combined with other survey data covering, for example, job vacancies, earnings, trade union membership, industrial disputes and productivity to provide a comprehensive picture of the way the labour market is performing.

The Labour Force Framework is a classification system, governed by a set of rules and categories. It forms the foundation for cross-country comparisons of labour market data. The framework is made operational through the International Labour Organization (ILO) and its International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). These conferences and expert meetings develop the guidelines or norms for implementing the labour force framework and generating the national labour force data.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics publication – Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods – describes the international guidelines that national statistical agencies agree on which define the organising principles that define the Labour Force Framework.

National statistical agencies work within internationally agreed standards when publishing labour statistics.

At the end of the First World War, the ILO was established (1919) to set minimum labour standards. Each year, there is an International Labour Conference that makes decisions that determine what are called the International Labour Conventions and Recommendations.

One section of these conventions, the – Labour Statistics Convention (No. 160) – was adopted at the 71st International Labour Conference in 1985 and modernised the previous convention that was agreed in 1938.

Article 1 of the 1985 Convention requires all member states of the ILO (including Australia and the US) to:

regularly collect, compile and publish basic labour statistics, which shall be progressively expanded in accordance with its resources to cover the following subjects:

(a) economically active population, employment, where relevant unemployment, and where possible visible underemployment;

(b) structure and distribution of the economically active population, for detailed analysis and to serve as benchmark data;

(c) average earnings and hours of work (hours actually worked or hours paid for) and, where appropriate, time rates of wages and normal hours of work;

(d) wage structure and distribution;

(e) labour cost;

(f) consumer price indices;

(g) household expenditure or, where appropriate, family expenditure and, where possible, household income or, where appropriate, family income;

(h) occupational injuries and, as far as possible, occupational diseases; and

(i) industrial disputes.

The ILO also publish very detailed technical guidelines about how these statistics should be collected and disseminated via one of its technical committees – the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). This Committee meets about every five years and its membership comprises government officials who are “mostly appointed from ministries responsible for labour and national statistical offices” and representatives from employer’s and worker’s organizations.

The ICLS agree on resolutions which then determine the way in which the national statistical offices collect and publish data. While the national statistical agencies have some discretion as to how they undertake the task of preparing labour statistics, in general, there is widespread uniformity across agencies.

Labour statistics are often drawn into political controversies and government critics have been known to accuse the government of manipulating the official data for political purposes. But once you understand the process, which governs the structure of the labour force statistical collection and the definitions outlined in the ICLS resolutions it is hard to make that argument.

This is not to say that there is not a lot of debate about what the official labour statistics measure and whether they can be improved but it is important to understand how they are collected.

The rules contained within the labour force framework generally have the following features:

- an activity principle, which is used to classify the population into one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework.

- a set of priority rules, which ensure that each person is classified into only one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework.

- a short reference period to reflect the labour supply situation at a specified moment in time.

The system of priority rules are applied such that labour force activities take precedence over non-labour force activities and working or having a job (employment) takes precedence over looking for work (unemployment). Also, as with most statistical measurements of activity, employment in the informal sectors, or black-market economy, is outside the scope of activity measures.

There is a long-standing concept of “gainful work”, which shape these priorities but have proven controversial. Gainful work is typically seen as work for profit that receives payment. So a person who does ironing for a commerical laundry would be considered to be pursuing gainful work whereas if the same person was ironing for their familty they would be considered inactive.

Clearly, with economic and non-economic roles being biased along gender lines, this distinction leads to an undervaluation of a substantial portion of work performed by females.

Thus paid activities take precedence over unpaid activities such that for example ‘persons who were keeping house’ as used in Australia, on an unpaid basis are classified as not in the labour force while those who receive pay for this activity are in the labour force as employed. Similarly persons who undertake unpaid voluntary work are not in the labour force, even though their activities may be similar to those undertaken by the employed.

The category of ‘permanently unable to work’ as used in Australia also means a classification as not in the labour force even though there is evidence to suggest that increasing ‘disability’ rates in some countries merely reflect an attempt to disguise the unemployment problem.

In terms of those out of the labour force, but marginally attached to it, the ILO states that persons marginally attached to the labour force are those not economically active under the standard definitions of employment and unemployment, but who, following a change in one of the standard definitions of employment or unemployment, would be reclassified as economically active.

Thus for example, changes in criteria used to define availability for work (whether defined as this week, next week, in the next 4 weeks etc.) will change the numbers of people classified to each group. This also provides a great potential for volatility in series and thus there can be endless argument about the limits applied to define the core series.

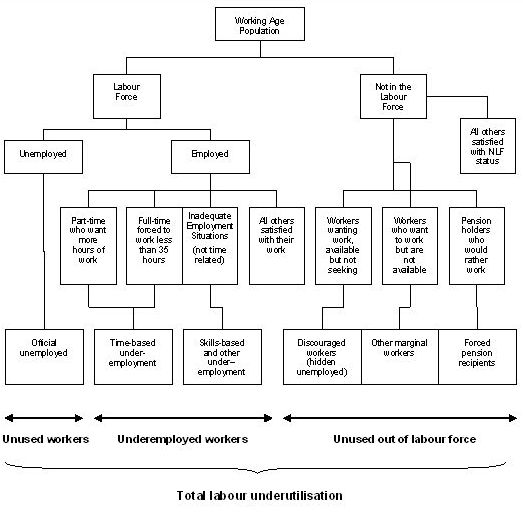

Figure 10.1 summarises the Labour Force Framework as it is applied in Australia but this is a common organising structure across all nations.

Figure 10.1 The Labour Force Framework

National statistical agencies conduct a Labour Force Survey (LFS) on a regular basis, usually monthly, which collects data using the concepts and definitions provided for in the Labour Force Framework.

The Working Age Population is typically all citizens above 15 years of age. In several countries, the age threshold is 16 years of age. In the past, the age span was 15 years to retirement age, usually around 65 years of age. However, as social changes have seen age discrimination laws come into force in many nations, the upper age limit has been accordingly abandoned in several nations.

The Working Age Population is then decomposed into the Labour Force (the “active” component) and Not in the Labour Force (the “inactive” component). A worker is considered to be active if they are employed or unemployed.

The proportion of workers who comprise the labour force is governed by the Labour Force Participation Rate, which is defined as:

… the ratio of the labour force to the working age population, expressed in percentages.

We will consider the cyclical behaviour of the participation rate later in the Chapter.

The ILO defines a person as being employed if:

… during a specified brief period such as one week or one day, (a) performed some work for wage or salary in cash or in kind, (b) had a formal attachment to their job but were temporarily not at work during the reference period, (c) performed some work for profit or family gain in cash or in kind, (d) were with an enterprise such as a business, farm or service but who were temporarily not at work during the reference period for any specific reason. (Current International Recommendations on Labour Statistics, 1988 Edition, ILO, Geneva, page 47).

What constitutes “some work” is controversial. In Australia, for example, a person who workers one or more hours a week for pay is considered to be employed. So the demarcation line between employed and unemployed is, in fact, very thin.

Within the employment category further sub-categories exist, which we will consider later. Most importantly, significant numbers of employed workers might be classified as being underemployed if they are not able to work as many hours as they desire because there is insufficient aggregate demand in the economy at that point in time.

What constitutes unemployment? According to ILO concepts, a person is unemployed if they are over a particular age, they do not have work, but they are currently available for work and are actively seeking work. Unemployed people are generally defined to be those who have no work at all.

Unemployment is therefore defined as the difference between the economically active population (labour force) and employment.

Two derivative measures capture a lot of public attention. First, the Unemployment Rate is defined as:

… the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the civilian labour force.

The US unemployment rate in October 2012 was 7.9 per cent. This was derived from a labour force estimate of 155,641 thousand and total estimated unemployment of 12,258 thousand.

Second, statisticians publish the Employment-Population ratio, which is:

… the proportion of an economy’s working-age population that is employed.

Note that the denominator of these two ratios is different. The unemployment rate uses the labour force while the employment-population ratio uses the working age population.

We will see why this difference matters later when we consider the way the labour market adjusts over the economic cycle and how this impacts on our interpretation of the state of the economy as summarised by the unemployment rate and the employment-population ratio.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Conclusion

I will be continuing this Chapter next week. Once the measurement section is finished the Chapter will turn to a theoretical discussion concerning the determination of employment and unemployment and the debates about real wages etc.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

Why do you think job vacancy statistics aren’t generally published alongside unemployment stats? Whenever new unemployment figures come out that’s always the first thing I go and compare them to.

Andi

If you remember that Southern French rural , inter village train line that I was talking about earlier in the year (they closed the line in July)

Well the bus route is now suspended…………..

http://www.midilibre.fr/2012/10/06/ales-besseges-les-bus-etaient-provisoires,573775.php

I really can’t see much wrong with the domestic French economy other then a very serious lack of Francs.

As the neo – liberal era polices of the 80s can be still be reversed quite easily (with the will) unlike countries such as the UK which is much further down this road.

The Euro boys obviously wish to rob all former nation states of domestic currency which made their internal commerce functional and thus more redundant and resilient to outside input shocks.

Who can not say now the European experiment is the greatest market state conspiracy in the history of mankind ?

French market towns were once the backbone of France.

Now that the hell are they ?

More conduits for the corporate fascist super state I imagine.