It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Aggregate Demand Part 1

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text by the end of this year. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Chapter 8 Expenditure, output and income and the multiplier

8.1 Introduction

In Chapter 7, we introduced the concept of effective demand, within the original aggregate supply-aggregate demand framework (D-Z) developed by Keynes in the General Theory. Recall that Keynes defined the aggregate supply price of the output derived for a given amount employment as the “expectation of proceeds which will just make it worth the while of the entrepreneur to give that employment” (footnote to Keynes, J.M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan, page 24 – check page).

We learned that this concept related a volume of revenue received from the sale of goods and services to each possible level of employment. At each point on the aggregate supply price curve, the revenue received would be sufficient to cover all production costs and desired profits at the relevant employment level.

The other way of thinking about the aggregate supply price Z-function is to express it as the total amount of employment that all the firms would offer for each expected receipt of sales revenue from the production that the employment would generate.

The important point here is that the relationship was expressed in terms of employment and the revenue expected to be received at each output level. We should be clear that Keynes was considering aggregate supply in terms of the expectation of proceeds, which is the money income (revenue) that the firms expect to get from selling their output. Firms are thus considered to formulate plans to gain a volume of money or nominal profits.

Why did he choose to employment instead of output itself? The reason relates to the developments in statistical gathering in the period that he was developing his theory (published 1936). National Accounting as we know it today (analysed in Chapter 5) did not exist in 1936. There were no reliable estimates of output (real GDP) but estimates of total employment were more accurate and more readily available.

It is for that reason that Keynes used employment instead of output as his measure of aggregate activity.

In this Chapter, we thus have two tasks. First, to express the model developed in Chapter 7 in terms of output rather than employment. Second, to express the supply side and the demand in real terms.

There are two aspects to conceiving of the income-expenditure framework in real terms. First we consider that consumers, firms and governments desire to achieve real outcomes in terms of the command on real resources (output) they gain when they spend. Second, to overcome the fact that the aggregate supply approach developed in Chapter 7 was cast in money (nominal) terms (revenue or proceeds) we need to recast the supply-side in real terms.

We can do that by using the National Accounting concept of GDP at constant rather than current prices as our measure of economic activity. In other words, we are considering that firms cast their price and output decisions based on expectations of aggregate spending in order to achieve a real return over costs.

In this way, we do not diminish the importance of expectations in driving production and supply decisions by firms but we abstract from price changes and assume that firms react to changes in aggregate spending by adjusting the quantity of output rather than the price and quantity. There are various ways in which we can justify considering firms to be quantity adjusters.

First, we might assume that there is typically excess capacity and firms use mark-up pricing (adding a mark-up to unit costs) and face roughly constant unit costs over the relevant range of output.

Second, we might assume that firms face various costs in adjusting prices and as a result only periodically make such adjustments. It has been said that firms use “catalogue pricing”, whereby they make their prices known to their prospective customers through advertising and other means and thus stand ready to sell goods and services at those prices irrespective of demand. At the end of the current catalogue, they will then make any necessary adjustments.

We consider pricing models in more detail in Chapter 9.

In terms of advancing a theory of employment, we now need to consider an employment requirements function, which relates the output that firms expect to sell (and therefore produce) to employment via a productivity relationship. If we know how many employment units (we abstract here from the issue of how we will measure these units – in hours or persons) are required to produce one unit of real output then once we know the sum of the firm’s production plans then we also will know the aggregate or macroeconomic demand for labour. We consider those issues in Chapter 10 when we formally introduce the labour market.

8.2 Aggregate Supply

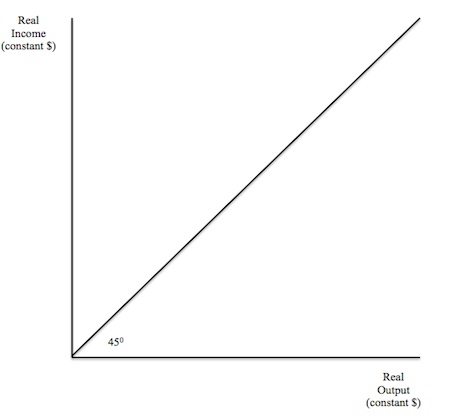

Figure 8.1 depicts the constant price aggregate supply relationship that we will work with in this Chapter to concentrate on the way the economy adjusts to changes in aggregate demand. It is drawn as a 450 line emanating from the origin with total revenue (in constant dollars) on the vertical axis and real output on the horizontal axis.

Obviously, without considering any economic meaning, the 450 line shows all points where real income (real expected proceeds) is equal to real output. Given that real expected proceeds and real income is equal to real expenditure then the 450 line shows all points where output and expenditure are equal (in constant prices).

But consider what the 450 line implies with respect to postulated firm behaviour.

Think back to Chapter 5 when we explained the different perspectives that we can take in measuring aggregate economic activity. The expenditure, income and output approaches provided different views of the national accounting framework but in the end all yielded the same aggregate outcome. The total value of goods and services produced in any period was equal to the total spending and the total income generated (wage and other costs and profits) in that same period.

As we will see in Chapter 9 when we consider aggregate supply in more detail, total output (measured in Figure 8.1 along the horizontal axis) is exactly equal to total input costs (incomes to suppliers of labour and other productive materials) and profits.

In that context, firms will supply that output (and incur those costs) as long as it can generate enough revenue to cover the costs and realise its desired profits.

The vertical axis provides a measure of total expenditure which also equals to real income. From the perspective of the firms the vertical axis tells it the real expected proceeds that it can generate by selling the different levels of output.

It is in this way that we can conceive of the 450 line as the aggregate supply curve (in constant prices). At each point the firms are realising their expectations and ratifying their decision to supply real output to the market. The ratification comes through the receipt of expected income that covers both their costs in aggregate and the desired volume of profits.

The other point to note is that we have imposed no full capacity point on the graph. At some point, when the economy is operating at full capacity, firms are unable to continue expanding real output in response to additional spending. When we introduce the expenditure side of the economy in the next section we will also impose a full employment output condition.

A diversion into employment

Before we consider the introduction of aggregate demand or expenditure into the model we will briefly show how this conception of aggregate supply based on expected proceeds translates into employment, given that we have real output on the horizontal axis now instead of employment.

We will deal with this question in detail in the next chapter but for now we introduce the concept of the Employment-Output function or the Employment Requirements Function, which shows the how much labour is required to produce a given volume of real output.

Firms hire labour to produce output. How much labour a firm hires will then be determined by how productive labour is and how much output the firm plans to produce.

The employment-output function is expressed as:

(8.1) Y = αN

where N is the total number of workers employment, α is the rate of labour productivity, and Y is planned output (based on expected spending), which is equal to the actual income generated in the current period. Firms produce based on expected aggregate spending and once all the sectors have made their spending decisions (that is, once aggregate demand is actually realised), the firms discover whether their expectations were accurate or not. That is, they discover whether they have overproduced, under-produced or produced according to the spending actions realised.

Labour productivity is defined as output per unit of labour input. So we could solve Equation 9.1 for α to get Y/N, which is the algebraic equivalent of our definition.

The higher is labour productivity (α) the less employment is required to produce a unit of output for a given production technique (implicit in α).

In Chapter 9, we will discuss the factors which influence the magnitude of α.

For now, if α is stable in the short-run (within the current investment cycle) then once the firm decides on the level of output to produce, to satisfy expected demand, it simultaneously knows how many workers must be employed.

Figure 8.2 ties the Aggregate Supply Function (depicted in Figure 8.1) together with the Employment-Output function. Once we add aggregate demand to the top panel (in the next section) then we will have determined total expenditure (aggregate demand), total output (aggregate supply), equilibrium output and income (the point of effective demand where the expenditure function intersects the aggregate supply function) and total employment.

The upper panel is Figure 8.1 repeated. The lower left-hand panel has not other purpose other than to map the horizontal axis in the top panel into the vertical axis in to the lower right-hand panel (which we have now called the Employment-Output Function). The slope of the Employment-Output Function is the current labour productivity (α).

So if firms are happy based on their expectations to produce output at point A, the we can trace that level of output down to determine the employment level that would be required to produce that level of output at the current value of α.

If there are not other changes, then if firms believe they can sell more output than before (say at point B) then this will necessitate a rise in employment, which is shown in the lower right-hand panel as point B. We can say the Employment-Output Function provides tells us the total employment requirements for any given level of output.

We will examine the Employment-Output Function in more detail in Chapter 9.

Figure 8.2 Aggregate Supply and Employment requirements

[NOTE: Remember the diagrams will be professionally drawn]

Clearly the story is missing one vital element – what determines whether Point A or B or any other is the level of output actually produced in any given period?

For this we need to build a model of expenditure – that is, the Aggregate Demand Function.

Aggregate Demand

[NOTE – a full derivation of the expenditure side of the economy will come next including the behavioural relationships and the expenditure multiplier]

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. I have tried to make it harder for all those who are complaining that it is too easy (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“if α is stable in the short-run (within the current investment cycle)”

How long is an investment cycle? Isn’t a better description “until investments require re-evaluation”. To me a cycle implies a predetermined time when in reality any shock can cause a re-evaluation of investments…

just my opinion.

Dan F, a cycle does not imply a fixed frequency ~ consider the business cycle, where the period from the onset of one recession to the onset of the subsequent recession takes however long it takes, and in the US has ranged over the past half century from a few years to nearly a decade.

.

And furthermore, if investment in productive capacity is a strategic decision, then for a given industry those decisions often are made on a regular calendar ~ its the content of the decisions that determines whether or not there is a change in the productive equipment which results in a change in alpha.

.

Indeed, how often do shocks result in an emergency investment in new productive capacity? … that is, as opposed to shocks that postpone new investment in productive capacity, which would stretch the period of the current investment cycle until after the emergency has passed and the business can assess whether or not to proceed with previously postponed projects.

“Second, to express the supply side and the demand in real terms.”

bill, could you verify (I’m going somewhere with this) that means there is a real aggregate supply curve and a real aggregate demand curve? Thanks!

“… what determines whether Point A or B or any other is the level of output actually produced in any given period?”

If prices increase people and investors will want to buy more, because next year it will be much more expensive, so the companies will want to produce and sell more and increase employment. But if prices decrease people will want to buy less, because next year it will be cheaper and companies will decrease employment and production.

If real interest rate is low, aggregate demand and total employment are increasing, if real interest rate is high, aggregate demand and total employment will decrease.

Remember Keynes:

“The policy of gradually raising the value of a country`s money to (say) 100 per cent above its present value in terms of goods amounts to giving notice to every merchant and every manufacturer, that for some time to come his stock and his raw materials will steadily depreciate on his hands, and to every one who finances his business with borrowed money that he will, sooner or later, lose 100 per cent on his liabilities (since he will have to pay back in terms of commodities twice as much as he has borrowed). Modern business, being carried on largely with borrowed money, must necessarily be brought to a standstill by such a process. It will be to the interest of everyone in business to go out of business for the time being; and of everyone who is contemplating expenditure to postpone his orders so long as he can. The wise man will be he who turns his assets into cash, withdraws from the risks and the exertions of activity, and awaits in country retirement the steady appreciation promised him in the value of his cash. A probable expectation of Deflation is bad enough; a certain expectation is disastrous.”

Keynes, »Social Consequences of Changes in the Value of Money« (1923), Essays, S. 189f.