It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

The British government has more than demonstrated its incompetence

Today’s article from the relics (my office clear out continues) is actually two articles. One by Arthur Okun and the other by fellow US macroeconomist Gardner Ackley. Both economists are now dead but during their careers were aware of the role of government in a monetary economy. They were antagonistic to the conservative views of economists that wanted to push fiscal rules such as balanced budgets. They understood that these views not only undermined democracy but also made it impossible for governments to pursue their legitimate goals of promoting public purpose. In the current environment, if they were still alive they would be castigating those who seek to impose pro-cyclical fiscal austerity. Their insights remain relevant today. Just think about yesterday’s public finance data release in Britain. The debt reduction forecasts from the British government are in tatters because tax revenue is collapsing further and welfare spending is rising. The operation of the automatic stabilisers is signalling that the British government has more than adequately demonstrated its incompetence.

The Arthur Okun article appeared – The Balanced Budget is a Placebo – in the May/June edition (VOL 23, NO. 2) of Challenge. Here is the JSTOR link if you have access to it.

The Gardner Ackley article – You Can’t Balance the Budget by Amendment – appeared in the November/December edition (Vol 25, No 5) of Challenge. Here is the JSTOR link if you have access to it.

The earlier article was an excerpt from the public statement that Arthur Okun made on March 10, 1980 to the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. It was his last public statement. He died about two weeks later at the age of 51 from a heart attack. Here is an interesting In Memoriam for Arthur Okun, who I considered to be a very useful economist in terms of his grasp of data and his resistance to the growing rational expectations, new classical school that took over Monetarism in the late 1970s. I learned a lot from Arthur Okun when I was a young economist – especially ways of thinking about data and ratios etc.

Arthur Okun said that:

Any anti-inflationary program that featured balancing the federal budget for fiscal 1981 as its main attraction would be an egregrious example of sheer symbolism. Suppose that federal expenditures for fiscal 1981 were reduced by $20 billion with no accompanying tax reduction or any other measure. That expenditure cut would amount to four-fifths of one percent of GNP. By the end of 1981, such a reduction might be expected to cut the total private and public expenditures for goods and services – by roughly 1.5 percent … That 1.5 per cent cutback in total national spending would be divided into two components: a reduction in the price level and a reduction in output … the statistical evidence indicates clearly that the reduction in output would be the larger component … All the evidence of U.S. price-wage behavior indicates that the payoff to this hypothetical program would be a mere fraction of a point on the inflation rate … Public officials must not fool themselves or the American public into believing that a balanced budget for 1981 is the cure for inflation.

He was writing in the early days of the disastrous Monetarist experiment that morphed (after it failed badly) into the even more pernicious neo-liberal period.

The rage of the day (late 1970s) was that budget deficits were inflationary (the inflation was courtesy of the supply shocks that followed the OPEC oil price rises). It was claimed that a short-sudden purge was required courtesy tight monetary policy and contractionary fiscal policy to rid the system of inflationary expectations.

At the time, the old guard Keynesians (like Okun and Ackley) were arguing against that position on the basis that the costs of the disinflation were huge and the gains small.

The Monetarists claimed that any costs (lost output and higher unemployment) would be minimal and ephemeral as the markets adjusted back to a low inflationary period.

The real question then was how large are the output losses following discretionary disinflation? The debate is clearly still apposite today.

While some extreme elements of the profession, who still consider rational expectations to be a reasonable assumption, will deny any real output effects, most economists acknowledge that any deliberate policy of disinflation will be accompanied by a period of reduced output and increased unemployment (and related social costs) because a period of (temporary) slack is required to break inflationary expectations.

To measure the real losses economists have used the concept of a sacrifice ratio which is the accumulated loss of output during a disinflation episode as a percentage of initial output expressed as ratio of the accumulated reduction in the inflation rate. The sacrifice ratio is related to Okun’s Law (coined by Arthur Okun), which is the percentage change in unemployment that accompanies a percentage change in the ratio of actual GDP to potential GDP.

If the sacrifice ratio was two it would mean that a one-point reduction in the trend inflation rate is associated with a GDP loss equivalent to 2 per cent of initial output. From Okun’s Law one could then estimate the accompanying rise in the unemployment rate.

The hardcore mainstream deny they exist in any meaningful way while other less manic mainstream economists suggest that they exist in the short-run only and are modest and ephemeral.

For example, in the famous September 1996 Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy set out how the Reserve Bank of Australia was approaching the attainment of its three identified policy goals (full employment, price stability and external stability). It elaborated the adoption of inflation targeting as the primary policy target.

In terms of the priorities, the Statement said (RBA, 1996: 2):

These objectives allow the Reserve Bank to focus on price (currency) stability while taking account of the implications of monetary policy for activity and, therefore, employment in the short term. Price stability is a crucial precondition for sustained growth in economic activity and employment.

The rest of the text emphasised the need to target inflation and inflationary expectations and the complementary role that “disciplined fiscal policy” had to play. There was no discussion about the links between full employment and price stability except that price stability in some way generated full employment even though the former required disciplined monetary and fiscal policy to achieve it.

The RBA said that the trade-off between inflation and unemployment while something that might be considered in the short-term is not a long-run concern because, following NAIRU logic, it simply doesn’t exist. They claimed that in the long-run the growth performance of the economy is determined by the economy’s innate productive capacity, and it cannot be permanently stimulated by an expansionary monetary policy stance. Any attempt to do so simply results in rising inflation.

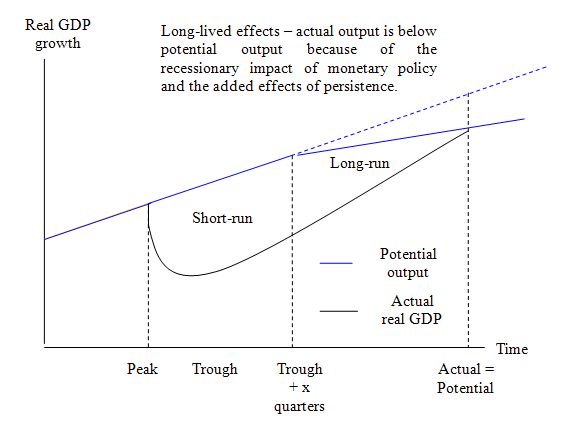

The following diagram is a simple graphical depiction of the sacrifice ratio concept and captures the way most empirical studies have pursued the estimation of sacrifice ratios. The cumulative output loss as a consequence of the actual output falling below potential output is depicted by the shaded area. In this diagram, output resumes at its potential level at the exact end of the disinflation period (defined as the period between the peak inflation and the trough inflation).

The resulting estimates of sacrifice ratios, even though they are still significant (around 1.3) are underestimates because they ignore the impacts of persistence and hysteresis. They assume that the disinflation episode has a relatively finite, short-term impact on real GDP growth and before long the actual growth path converges on the potential path (which was unchanged by the policy change).

However, in the real world, it is clear that a prolonged period of reduced real GDP growth lasts beyond the formal disinflation period and that the potential real GDP growth path also declines as the collateral damage of low confidence among firms curtails investment (which slows down the growth in productive capacity).

Persistence assumes that actual output is assumed to remain below potential after the disinflation period has finished. The longer this disparity exists the longer is the persistence. Hysteresis theories purport permanent losses of trend output as a consequence of the disinflation. I published an often-cited paper in 1993 (Applied Economics) on the issue of persistence and hysteresis (and covered it in my PhD research).

The important point is that to estimate the sacrifice ratio you have to not only consider the short-term losses but also the longer-term losses arising from persistence and hysteresis.

The following diagram captures these impacts and shows that the losses are much greater than would be estimated using the concepts in the first diagram (above). You can see that potential output falls after some time (as investment tails off) and actual output deviates from its potential path for much longer. So the estimated costs of the disinflation (and fiscal austerity supporting it) are much larger.

So the real question then is how large are the output losses following discretionary disinflation? Focusing on variability is unlikely to give you much of an idea of the welfare losses (or benefits) arising from the policy stance.

Empirical estimates of the sacrifice ratio show that the period of the Great Moderation was certainly not costless.

In my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned, we consider the estimation of sacrifice ratios in some detail.

The conclusions we draw from an extensive literature analysis and our own empirical work are:

- Formal econometric analysis does not support the case that central bank inflation targeting delivers superior economic outcomes. Both targeters and non-targeters enjoyed variable outcomes and there is no credible evidence that inflation targeting improves performance as measured by the behaviour of inflation, output, or interest rates.

- There is no credible evidence that central bank independence and the alleged credibility bonus that this brings bring faster adjustment of inflationary expectations to the policy announcements. There is no evidence that targeting affects inflation behaviour differently.

- Sacrifice ratios estimates confirm that disinflations are not costless; the average ratio for all countries over the 1970s and 1980s episodes is around 1.3 to 1.4. Significantly, the average estimated GDP sacrifice ratios have increased over time, from 0.6 in the 1970s to 1.9 in the 1980s and to 3.4 in the 1990’s. That is, on average reducing trend inflation by one percentage point results in a 3.4 per cent cumulative loss in real GDP in the 1990s.

The work I have done in this field which is summarised (with references) in the book show that the Great Moderation was actually associated with higher sacrifice ratios.

Australia, Canada, and the UK, who announced policies of inflation targeting in the 1990s, do not have substantially lower sacrifice ratios compared to G7 countries who did not announce such policies. Australia does record a lower average ratio during the targeting period than in the 1980s, averaged across the three methods it is 1.2 per cent, however this figure is not lower than the average for all previous periods. Canada records a higher sacrifice ratio in the 1990s of 3.6 per cent. The ratio for the UK during inflation targeting is significantly higher at 2.5 per cent (relative to quite low sacrifice ratios in previous periods). Meanwhile Italy, Germany, Japan and the US, average 0.6, 2.3, 2.9 and 5.8, respectively. Thus inflation targeting does not appear to have produced better outcomes in terms of reducing the costs of disinflation (although obviously we have not controlled for other factors).

The evidence is clear that inflation targeting countries have failed to achieve superior outcomes in terms of output growth, inflation variability and output variability; moreover there is no evidence that inflation targeting has reduced persistence.

Other factors have been more important than targeting per se in reducing inflation. Most governments adopted fiscal austerity in the 1990s in the mistaken belief that budget surpluses were the exemplar of prudent economic management and provided the supportive environment for monetary policy.

The fiscal cutbacks had adverse consequences for unemployment and generally created conditions of labour market slackness even though in many countries the official unemployment fell. However labour underutilisation defined more broadly to include, among other things, underemployment, rose in the same countries.

Further, the comprehensive shift to active labour market programs, welfare-to-work reform, dismantling of unions and privatisation of public enterprises also helped to keep wage pressures down. It is clear from statements made by various central bankers that a belief in the long-run trade off between inflation and employment embodied in the NAIRU has led them to pursue an inflation-first strategy at the expense of unemployment.

Disinflations are not costless. Sacrifice ratios have risen for the seven countries from on average 0.7 in the 1970s to 3.5 in the 1990s. This implies that any attempt to bring down inflation nowadays with 1 per cent-point will result in a cumulative loss in GDP of 3.5 per cent on average.

In terms of unemployment the latter can be interpreted roughly speaking as a cumulative increase by 7 per cent.

The increase in the sacrifice ratio over time illustrates that reduced inflation variability allows more certainty in nominal contracting with less need for frequent wage and price adjustments. The latter in turn means less need for indexation and short-term contracts and leads towards a flatter short-run Phillips curve. Thus a consequence of inflation targeting is that the costs of disinflation become higher.

This is what Arthur Okun was warning us about just before his death. He would have been horrified to see what happened since that time in terms of the development of policy and the deliberate use of unemployment as a policy tool rather than a policy target.

In 2000, the late Franco Modigliani said that (‘Europe’s Economic Problems’, Carpe Oeconomiam Papers in Economics, 3rd Monetary and Finance Lecture, Freiburg, April 6, page 3):

Unemployment is primarily due to lack of aggregate demand. This is mainly the outcome of erroneous macroeconomic policies … [the decisions of Central Banks] … inspired by an obsessive fear of inflation, … coupled with a benign neglect for unemployment … have resulted in systematically over tight monetary policy decisions, apparently based on an objectionable use of the so-called NAIRU approach. The contractive effects of these policies have been reinforced by common, very tight fiscal policies (emphasis in original)

However, the real costs of inflation targeting lie in the ideology that accompanies it such that fiscal policy has to be passive. The failure of economies to eliminate persistently high rates of labour underutilisation despite having achieved low inflation is directly a consequence of this fiscal passivity.

Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this point.

Gardner Ackley’s article is about fiscal surplus (or balanced budget) obsessions. So like Arthur Okun’s concern still very alive as an issue today some 30 years on. A blind adherence to ideology prevents learning. There has been very little learning over the last three decades among economists.

He was writing at the time the Reagan administration was trying to ram through the US Congress a Constitutional Amendment requiring the federal government to at least balance its budget at all times. The proposal was defeated 287 to 187 but the same issue continues to raise its head. Further, the European nations are increasingly imposing these sorts of fiscal rules.

The IMF recommends that fiscal rules be the norm.

Gardner Ackley wrote that the “proposed Constitutional Amendment”:

… lacks economic or political justification. Its enactment … would severely damage the ability of the federal government effectively to carry out its responsibilities, and could significantly reduce the welfare of the American people.

Fiscal policy has to operate flexibly to meet the flux and uncertainty of non-government spending. If it becomes so constrained that it can no longer provide the necessary adjustment (stimulus or contraction) to offset private spending changes in a counter-cyclical fashion then unemployment and/or inflation are inevitable.

The neo-liberal obsession with fiscal rules biases the costs of any loss of fiscal flexibility towards mass unemployment (given the rejection of deficits).

Gardner Ackley then considered the objection to fiscal policy activism – which means in the parlance – using deficits to support demand. I have always found that term odd given that fiscal austerity is considered the reverse of activism. I see activism as using fiscal policy to alter aggregate demand and therefore output and employment.

In that context, the government can choose to be active responsibly – that is, to provide active counter-cyclical support (stimulus when non-government demand is weak and brakes when non-government demand is strong) – or it can act irresponsibly and kill growth and deliberately push up and prolong unemployment with pro-cyclical measures.

Gardner Ackley challenged the notion that there “an inevitable tendency exists for democratic governments to overspend, and therefore, perhaps, to overtax.”

He actually thought the bias in the US at the time (which would be the same now) is the reverse:

Our taxes are mainly direct taxes … and thus highly visible – to a completely enfranchised taxpaying public. On the other hand, government expenditures are scattered over a multitude of complex programs, serving a wide variety of public interests. In this situation, the more relevant phenomenon may be the “tax revolt” – by voters most of whom know or care very little about many of the purposes and results of government spending, but who are very conscious of their taxes.

In other words, he believed that the balanced budget proposals were really about advancing a “tax revolt” although history tells us that the most vocal opponents of fiscal deficits were mostly concerned with their own narrow welfare and never argued for expenditure cuts that might damage their pet project, industry or specific firm.

Gardner Ackley also thought that such proposals “had disturbing implications for believers in representative government”:

By permitting a minority of two-fifths of the membership of either House to block actions supported by a substantial majority … it implies that our representative system cannot be trusted to make intelligent choices in budgetary matters. If this is the case for taxes and spending, can we trust it for questions involving social relations, education, foreign affairs, and civil rights?

And one might add (if foreign affairs doesn’t cover it) – billions spent on the military.

I have always found the argument that we have to limit the capacity of government because we cannot trust them to be spurious and cannot be logically sustained for exactly the reasons Gardner Ackley notes.

The extremists, of-course, would privatise everything – militias, police, everything. But then civilisation would collapse as we rehearsed that primordial phase of human existence.

The challenge is to keep any tendencies towards incompetence or dishonesty by government in check. That requires a well-educated populace who are involved in civic affairs and a free press. It requires substantial protection of whistleblowers and independent institutions with judicial powers to be working properly. It requires that the public funds all political campaigns and the like and that the media concentration is contained.

That is what progressives should be pushing for at all times – to keep them honest.

But in a modern monetary system – the government is the central player – and we just cannot eliminate that currency-issuing capacity and all that goes with it.

Gardner Ackley then provides the economic case against balanced budget proposals. He says:

My own position on deficits has always been, and remains, that deficits per se, are neither good nor bad. There are times when they are not only appropriate but even highly desirable; and there are times when they are inappropriate and dangerous. During a recession or a period of “stagflation”, deficits are nearly unavoidable, and are likely to be constructive rather than harmful. An attempt to balance the budget in recession years such as 1954, 1960, 1970-71, 1975, or 1981-82, by raising taxes or cutting expenditures, would be prohibitively costly – in jobs, production, and real incomes – and perhaps even impossible to achieve on any terms.

He argues that deficits should be reduced when the economy is growing strongly on the back of non-government spending growth.

The point is that:

Some deficits are good; some are bad. Prohibiting them, or making them more difficult, not only limtes the ability of the government to stabilize the economy, but can be positively destabilizing.

Gardner Ackley wrote a textbook that was popular in the 1960s and into the 1970s. It was first published in 1961 and reprinted in 1978. It offered a classic Keynesian approach, which we might disagree with in its totality, but in terms of the fundamental insights into the expenditure system it was spot on.

He understood and his students learned that SPENDING EQUALS INCOME EQUALS OUTPUT which drives EMPLOYMENT. The basic first rule of macroeconomics. He knew that fiscal contraction expansions (the mantra of those proposing fiscal austerity) was a denial of reality.

He knew that when the private sector is enduring persistently high levels of unemployment and its wealth (overall) has taken a beating that consumers will become less profligate and firms will have less need to invest in more capital equipment.

He knew that in those circumstances the economy could only grow out of that pessimism and spending malaise if the government intervened with its fiscal capacity and filled the spending gap. The intervention would immediately stimulate growth and employment and help the non-government sector save without cutting consumption and investment. It would allow the households and firms to regain some confidence in the future.

Gardner Ackley then considered the arguments used to justify the balanced budget proposal. He noted that at that time the US economy was languishing and deficits were rising – again the same circumstances that have prevailed for the last 4-5 years.

He noted:

It is easy, therefore, to hypothesize that the deficits are responsible for our poor economic performance. That hypothesis has been strongly expressed by President Reagan, by many members of Congress, and by many important leaders in the private sector. Unfortunately, such “post-hoc, propter-hoc” reasoning is – as is often the case – basically erroneous.

It is much closer to the truth … to say that the main causal relationship between deficits and the state of the economy runs in exactly the opposite direction: a weak and poorly functioning economy is responsible for most budget deficits.

Which is why in the earlier quote he indicated that a government would most likely fail if it tried to reduce the deficit at a time when it should, on economic grounds, be increasing it. That is, fiscal austerity will be “impossible to achieve on any terms” if its aim is to reduce the deficit.

Gardner Ackley calls the “dependence of the budget outcome on the state of the economy” an “obvious” thing – although it seems to escape the perception of those who advocated fiscal austerity.

He then outlined the concept of a full employment budget balance – where the budget balance is adjusted for cyclical impacts.

We know that tax revenue and welfare payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when growth in times of downturn and the former rises in times of growth and falls during a downturn.

These components of the Budget Balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers because the recorded Budget Balance will vary over the course of the business cycle, even if the discretionary policy settings remain unchanged. The automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

As a result, we cannot conclude that a rising budget deficit indicates that the government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. Any statements that suggest the budget deficit is “too large” and that program cut-backs are required to address the situation thus have to be assessed with considerable caution.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what was called the Full Employment Budget to benchmark the actual budget balance against. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The Structural Balance is a hypothetical budget balance that would be realised if the economy were operating at potential capacity or full employment. In other words, the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) would be calibrated against some fixed point (full capacity) and thus eliminate the swings in the budget balance that arise from variations in the business cycle. These cyclical swings in activity around full employment or capacity would be separated out from the underlying budget position, which would then reflect the discretionary fiscal stance chosen by the government.

If the structural component of the budget outcome is balanced then it means, conceptually, that total outlays and total revenue would be equal if the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget were in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary fiscal stance was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

An important point to understand is that the actual budget balance is to a major extent out of the control of the government because the cyclical component reflects the variations in the spending decisions of private sector agents (household, business firms, external relations).

As a result, it is often counter-productive for a government to attempt to target a reduced budget outcome with discretionary spending cuts and/or taxation increases because it fears the budget balance is excessive. In these circumstances, the imposition of austerity will most likely cause real growth to contract and the automatic stabilisers to push the budget further into deficit. It also follows that a growth strategy underpinned by discretionary stimulus spending and/or tax cuts can drive reductions in the budget deficit outcome as the level of economic activity increases and tax revenues recover.

The motivation for discussing these “old” articles is not to reprise history for its own sake. I love history but that is not the motivation here. The fact is that the economists I have been discussing this week did understand the basic foundations of macroeconomics. That understanding is no longer being reflected in policy because the opponents of these wise men (mostly) or their scions are now in charge and wreaking havoc.

In other words, their insights are extremely prescient in the curret debate.

Consider yesterday’s data release from the British Office of National Statistics – Public Sector Finances, July 2012 which has detailed how the forward estimates by the British Treasury in the last Budget have been blown out of the water by the deteriorating British economy. Who would have thought?

The British Office for Budget Responsibility had forecast that borrowing would fall from £125bn in 2011 to £122bn this year.

Yesterday’s data, which showed that corporate tax revenue has fallen off a cliff and that:

Public sector net borrowing was £0.6 billion in July 2012; this is £3.4 billion higher net borrowing than in July 2011, when net borrowing was -£2.8 billion (a repayment)

In July 2012, central government accrued current receipts were £52.5 billion, which was £0.4 billion, or 0.8 per cent, lower than in July 2011, when central government current receipts were £52.9 billion.

In July 2012, central government accrued current expenditure was £50.2 billion, which was £2.4 billion, or 5.1 per cent, higher than July 2011, when central government current expenditure was £47.8 billion.

In 2011/12, the central government accrued current expenditure was £617.0 billion, which was £10.4 billion, or 1.7 per cent, higher than in 2010/11, when central government current expenditure was £606.6 billion.

The rise of £10.4 billion is due to a rise in debt interest payments of £2.6 billion, a rise of net social benefits of £8.3 billion and a fall in other expenditure of £0.4 billion.

You get the drift = tax revenue is falling and government spending is rising mainly because of “a rise in net social benefits” (relating to unemployment and disadvantage). As a result the deficit is higher than predicted and so net borrowing is also much higher than estimated.

Conclusion

The lesson is simple – pro-cyclical fiscal policy will fail to achieve its own manic aims and in attempting to do so will cause severe damage to the economy – which means – never forget it – the people who lose their jobs, their families, their communities.

The British government has now been in power for two and a half years and has more than adequately demonstrated its incompetence.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Our governments are peopled with detached, unfeeling bureaucrats and technocrats. Things aren’t like they used to be. Politicians don’t graduate from small-town fire departments and haberdashery stores and go on to reach high office. Even the low-level staffers, these days, come from top schools. They are part of the new oligarchy, albeit a very junior part. The only thing they care about is a career.

They never forget about ordinary people, though – “the people who lose their jobs, their families, their communities.” But it’s because they don’t have to – they’ve never met any.

Just look what they did to Glasgow…… they are capable of anything really.

Now Glasgow was always a very rough city, but it had some money withen it during the 60s which kept things from imploding.

Post 1980 it of course underwent a Soviet like controlled implosion as London could make more money from Global wage arbitrage operations rather then any form of domestic Industrial activity

Look at the contrast in dress sense (discount the 70s fashion) and almost everything else between the mid 1960s , the late 70s and the bottom in the early 90s……

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kgOw9crjzMg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGeHgdMVujM

Rock bottom ?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kuKZWkgo098

Now Rangers are bankrupt ………

Maybe the days of The UK recycling global monetary & petro flows back into soccer & calling it growth has reached its terminus.

“You get the drift = tax revenue is falling and government spending is rising mainly because of “a rise in net social benefits””

Perhaps it didn’t happen last year partly because the austerity was mainly tax rises which out-weighed any rise in welfare outlays last.

I’m curious to know, Bill, how you would calculate a full employment budget balance, or if you think it is even necessary. I would simply respond to what is actually happening in terms of inflation, unemployment and other important aggregates as they become known each year, then look back historically to see what the full-employment budget balance must have been.

Kind Regards

“The work I have done in this field which is summarised (with references) in the book show that the Great Moderation was actually associated with higher sacrifice ratios.”

Bill, do you think this is tied to the fact that many people now think monetary policy is very effective. I.e. Is the effectiveness of monetary policy to control inflation really due to its significant impacts on aggregate demand due to high sacrifice ratios?