I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The comedian still trying to make us laugh

Crazy ideas have a habit of re-entering the public policy debate even if they have been comprehensively rejected in theoretical and/or empirical terms. In fact, the whole edifice of neo-liberal thinking, which dominates the public debate now, was discredited by Keynes and others during the Great Depression and fell into irrelevance for most of the Post World War 2 growth period which delivered full employment. There are sub-sets of crazy ideas within the neo-liberal narrative that are in a similar position. In the early 1980s, we started to be barraged with what is known as supply-side economics, which amounted to a categorical rejection of demand-side measures (active fiscal policy intervention). One of the major claims of the supply-side approach was that deregulation and large tax cuts for the high income earners and companies would generate massive increases in real GDP growth (and national income) which would trickle down to the low-income earners. To fit this into the neo-liberal rejection of budget deficits they also had to come up with the claim that the tax cuts would actually generate offsets in tax revenue and improve the budget balance. This was the comedy that became known as the Laffer Curve. The economist who was pushing that line in the 1980s has also maintained an intense opposition to any use of fiscal policy to stimulate real GDP growth. He claims that the recent history shows that fiscal policy expansion damages growth. But when you dig into his argument you realise that the comedian is still trying to make us laugh. The only problem is that he isn’t very funny.

There was a recent reminder of the ideological emphasis of Arthur Laffer’s work in the UK Guardian article (June 27, 2012) – So the Laffer curve says tax cuts for the rich? This isn’t going to be funny.

The article says that:

Two comedians have been put in the spotlight in the current debate that has been opened up on tax in Britain. One is Jimmy Carr. The other is Arthur Laffer.

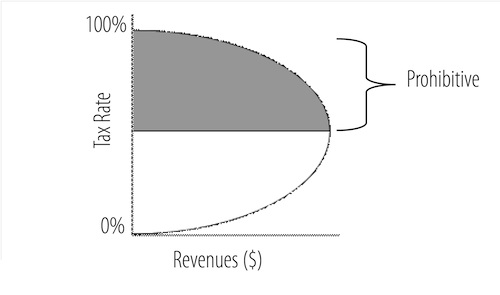

Arthur Laffer, a US economist came to prominence in the 1980s under the umbrella of the Ronald Reagan’s US presidency. Laffer produced the so-called “Laffer Curve” (see next graph) which basically claimed that tax cuts pay for themselves by ensuring the growth in real GDP generates the extra tax revenue loss via the rate cuts and keeps the budget balanced.

As the Laffer Center itself (which still promotes the idea) says:

The Laffer Curve is one of the main theoretical constructs of supply-side economics, and is often used as a shorthand to sum up the entire pro-growth world view of supply-side economics.

From which you can conclude that supply-side economics has major theoretical flaws.

But it was an ingenious device because it played fully to the “trickle-down” narratives that were abroad at that time which really amounted to elaborate justifications to give tax cuts to the high income earners and none to the low income earners.

It also showed how these tax cuts could still be consistent with the other mantra of the day – the need for balanced budget.

So conservatively-oriented governments could have it both ways – provide largesse to their mates (high income earners) via the tax cuts – but still claim to being fiscal conservatives aiming for surpluses or at worse balanced budgets. It seemed too good to be true and usually when that is the perception it is also the reality.

It was in other words a major con-job. The Guardian article refers to Arthur Laffer as a comedian. I would probably use other words. The idea was not Laffer’s originally (having been around as far back as David Hume (in his 1756 essay Of Taxes) but it was Laffer who became the modern proponent of the idea.

The good thing that the idea was one of the crazy trickle-down policies actually implemented by the Reagan Administration. In 1981, Reagan began his trickle-down presidency with a large tax cut to companies courtesy of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) – the largest in US history. In the following three fiscal years

I haven’t the time today to go into that 8-year period in detail. For those who were not around then or are not familiar with US fiscal history the fact is that Reagan began his tenure with a large tax cut courtesy of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) – one of the largest tax cuts in the period since World War 2. The Act provided for a 3-year phased in 23 per cent cut across the board income tax cut and large concessions (deductibles) for companies. There were changes to the tax structure (indexed brackets etc)

His 1986 he introduced the Tax Reform Act which lowered the top marginal tax rate from 50 per cent to 28 per cent but increased the lowest rate from 11 per cent to 15 per cent.

Taken together the 1981 and 1986 tax acts reduced the top income tax rate from 70 per cent to 28 per cent.

At the end of his first year as President the budget deficit was 2.6 per cent of GDP but by 1983 it rose to 6 per cent and remained at 5 per cent through to 1986. To address the declining tax revenue (partly because of the tax cuts and partly because of the recession at the time), Reagan made two other significant tax changes – in 1982 and 1984 which some claim were the largest tax increases in a peacetime period.

But the point was that income taxes were spared. These changes involved a broadening of the tax base which disadvantaged the lower income groups. He also increased the payroll tax (a tax on employment).

The Guardian article argues that during Reagan’s period of office:

… taxes were cut for higher earners while workers paid more. Corporate and capital gains tax rates were also cut in an earlier outing for current “austerity” policies, the transfer of incomes from labour and the poor to capital and the rich.

But despite this tax revenue fell when he cut the top income brackets rather than increased. There is a host of academic research which shows the Laffer Curve idea is bunk.

Even mainstream economists can see no merit in the idea. In a recent survey (June 26, 2012) conducted by the IGM Economic Experts Panel – coordinated by the the Booth School at Chicago University (so hardly heterodox) not one of the panel thought a “cut in federal income tax rates in the US right now would raise taxable income enough so that the annual total tax revenue would be higher within five years than without the tax cut”. The weighted responses suggested that 57 per cent strongly disagreed and an additional 39 per cent disagreed (4 per cent we uncertain).

You might like to read this interesting and easy to understand critique of the Laffer Trickle-Down myth – Trickle-Down Economics: Four Reasons Why It Just Doesn’t Work.

Anyway, the reason I mention this little snippet of history is because Dr Laffer is now lecturing the world on how fiscal stimulus packages generate worse real GDP growth outcomes than austerity.

In a recent Wall Street Journal article (August 5, 2012) – The Real ‘Stimulus’ Record – Arthur Laffer has the temerity to argue that:

In country after country, increased government spending acted more like a depressant than a stimulant.

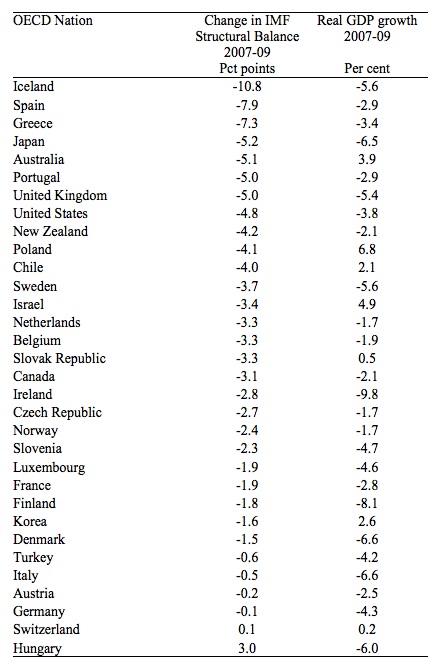

He presents a Table (sourced from the IMF) to back up his claim. I reproduce it here. It is based on data from the International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2012. The sample covers the full list of OECD nations so there is some logic in that regard although he would have been better using the entire WEO database (but I understand that takes time and is too complicated a story for an Op Ed – so no criticism there).

Let’s see what the argument is.

Dr Laffer says that:

Policy makers in Washington and other capitals around the world are debating whether to implement another round of stimulus spending to combat high unemployment and sputtering growth rates. But before they leap, they should take a good hard look at how that worked the first time around.

It worked miserably, as indicated by the table nearby, which shows increases in government spending from 2007 to 2009 and subsequent changes in GDP growth rates. Of the 34 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development nations, those with the largest spending spurts from 2007 to 2009 saw the least growth in GDP rates before and after the stimulus.

The four nations-Estonia, Ireland, the Slovak Republic and Finland-with the biggest stimulus programs had the steepest declines in growth. The United States was no different, with greater spending (up 7.3%) followed by far lower growth rates (down 8.4%).

First, note the dates being used to render the argument. The spending variable is the change 2007-09 while the real output measure is for 2006-07 to 2008-09. He is using the change in the real GDP growth rate rather than the real GDP growth rate itself because he realises that cyclical effects will contaminate his analysis. I discuss that soon.

But the better measure of the real output response to the fiscal stimulus measures would be to lead the measures a bit and lag the response. So we might more reasonably expect real GDP to respond in 2008 and 2010 to a fiscal stimulus between 2007 and 2009.

Second, note the measure of fiscal stimulus he is using. Change in government spending as a percent of GDP. Most economists would consider that a partial and tainted measure at best.

The ratio – spending on top and nominal GDP on the denominator is an ambiguous measure of the chosen fiscal position because it can rise while the government is cutting discretionary spending and fall when it is increasing discretionary spending.

How does that come about? Simply because if fiscal austerity (discretionary spending cuts) undermine aggregate demand (that is, are not replaced by an offsetting increase in private spending) then GDP will decline and the ratio would rise if the decline in GDP is faster than the spending cuts. The opposite, obviously could occur as well.

Further, a point I will return to, the relationships in the Table hide the causality involved. In this blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – I explain the way in which changes in the business cycle impact on the budget balance bottom line.

By way of summary, the national government budget balance is the difference between total revenue received by that government and its total outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa.

Many claim that the budget balance indicates the fiscal stance (stimulatory, neutral, or contractionary) of the government. So if the budget is in surplus they conclude that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit they say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

A rising budget deficit is clearly expansionary and vice versa. But we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are so-called automatic stabilisers operating.

The most simple model of the budget balance can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the automatic stabilisers – automatic because they rise and fall with the cycle.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the Budget Balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the Budget Balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the Budget Balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time. In particular, we cannot conclude that a rising budget deficit is a sign that the particular government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind.

The same goes for rising government spending of-course. It can easily rise via the automatic stabilisers if the economy tanks badly (real GDP growth collapses and unemployment rises).

It is thus of no surprise to see a negative relationship between real GDP growth and government spending over a sample we know was defined by the worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. If we conducted the same analysis over a period of high growth the relationship would likely reverse. More later on this.

As I discuss in the last linked blog – to overcome this uncertainty in interpretation, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. In other words, they sought to construct a measure of the discretionary fiscal stance which is independent of the particular point in the business cycle where the observation is being made.

That is, they sought a measure of the budget balance which had decomposed the automatic stabiliser (the cyclical) component from that component which would arise if the economy was at some full employment or potential maximum output position.

While there are major disputes about how to decompose the actual budget balance into these two components the logic is sound. Dr Laffer would know that logic but categorically fails to qualify his conclusions.

In that light, the change in the spending to GDP ratio tells us nothing about what is happening on the revenue side of the budget. To determine the overall discretionary fiscal position, we thus need to consider the relative movements in spending and taxation revenue. That is, spending as a proportion of GDP might be rising at the same time as the tax take as a proportion of GDP is rising and stifling growth.

Under these circumstances, we would observe the correlation in the Table but would not be able to construct that correlation as saying anything about the relationship between fiscal stimulus and real GDP growth. Dr Laffer would also know about that but doesn’t mention it to his readers other than to say the following:

In many countries, an economic downturn, no matter how it’s caused or the degree of change in the rate of growth, will trigger increases in public spending and therefore the appearance of a negative relationship between stimulus spending and economic growth. That is why the table focuses on changes in the rate of GDP growth, which helps isolate the effects of additional spending.

This sleight of hand doesn’t isolate the effects. The acceleration in the plunge in real GDP growth is still negatively related to the automatic stabiliser component of spending and taxation.

Further, if you compare the data in a downturn phase of the cycle you will get different results than if you compare the data in a upturn. It would be better to consider a complete business cycle rather than just focus on a major downturn.

Dr Laffer draws on the Table to say that:

If you believe, as I do, that the macro economy is the sum total of all of its micro parts, then stimulus spending really doesn’t make much sense. In essence, it’s when government takes additional resources beyond what it would otherwise take from one group of people (usually the people who produced the resources) and then gives those resources to another group of people (often to non-workers and non-producers).

Often as not, the qualification for receiving stimulus funds is the absence of work or income-such as banks and companies that fail, solar energy companies that can’t make it on their own, unemployment benefits and the like. Quite simply, government taxing people more who work and then giving more money to people who don’t work is a surefire recipe for less work, less output and more unemployment.

First, a stimulus is an injection of net government spending. That can arise through a combination of tax cuts and/or spending increases. It is obvious that tax rates in most nations pursuing stimulus did not rise. Tax revenue also plummetted in most nations as the automatic stabilisers kicked into play as real GDP growth collapsed.

It is also obvious from a study of the data (which Dr Laffer would easily know) that the increases in budget deficits were matched by sales of bonds to the private sector. While that voluntary act by governments is unnecessary the fact remains that it wasn’t an act that “takes additional resources … from one group of people” (“the producers”) to give to the inert (“non-producers”).

Bond purchasers just swapped one financial asset (bank reserves) for another (the bond). If the bond purchasers had have instead spent the funds by way of consumption or investment spending then the budget deficits would not have risen as much and the real GDP growth rates would not have fallen so much (if at all). It is clear that the government just borrowed back funds that it had injected into the economy as I explained in yesterday’s blog – Budget surpluses are not national saving – redux.

Dr Laffer knows that income tax rates did not rise as part of this process and so his comment that “government taxing people more who work and then giving more money to people who don’t work is a surefire recipe for less work, less output and more unemployment” is gratuitous in the extreme.

But Dr Laffer is intent on misleading his readers. He argues that:

Well, the truth is that government spending does come with debits. For every additional government dollar spent there is an additional private dollar taken. All the stimulus to the spending recipients is matched on a dollar-for-dollar basis every minute of every day by a depressant placed on the people who pay for these transfers. Or as a student of the dismal science might say, the total income effects of additional government spending always sum to zero.

The point is which “private dollar” and the spending impact of the dollar spent against the dollar taken. An increase in government spending clearly adds to aggregate demand – $-for-$. So what about the offset?

Selling bonds to those who want to swap non-interest bearing (or close to it) reserves for bonds does not reduce private spending.

Even if an injection of government spending was “matched” by an equal increase in tax revenue (the so-called balanced budget multiplier) the fact that some of the tax rate increase would come from saving (the marginal propensity to consume is typically less than one) means that the addition to aggregate demand from the government spending increase would be higher than the loss of demand from the tax rate increases.

Dr Laffer concludes that his argument:

… is just old-timey price theory, the stuff that used to be taught in graduate economics departments.

From which you can conclude that “old-timey price theory” (the stuff that is still taught in most economics departments) has no credibility when applied to macroeconomics, quite apart from the problems with it at the microeconomic level (which are many).

Dr Laffer concludes that his “evidence”:

… is extremely damaging to the case made by Mr. Obama and others that there is economic value to spending more money on infrastructure, education, unemployment insurance, food stamps, windmills and bailouts.

The problem is that his “evidence” doesn’t tell us very much about the impact of discretionary increases in net public spending.

I had a look at the data myself. The IMF publish a measure in their WEO database which they call – General government structural balance (GGSB_NPGDP). They describe that measure in this way:

The structural budget balance refers to the general government cyclically adjusted balance adjusted for nonstructural elements beyond the economic cycle. These include temporary financial sector and asset price movements as well as one-off, or temporary, revenue or expenditure items. The cyclically adjusted balance is the fiscal balance adjusted for the effects of the economic cycle; see, for example, A. Fedelino. A. Ivanova and M. Horton ?Computing Cyclically Adjusted Balances and Automatic Stabilizers? IMF Technical Guidance Note No. 5, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/tnm/2009/tnm0905.pdf.

In this blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – I explain why these measures of the “full employment budget balance” are biased towards expansion. Basically, the benchmark full employment position assumed is usually based on some notion of the NAIRU or similar, which biased the full employment unemployment rate upwards.

In other words, true full employment is likely to be lower than the unemployment rate used by the IMF (or most of these institutions). That means that they underestimate the full employment tax revenue and overestimate the full employment public spending with the result that they usually conclude the discretionary budget position (the structural balance) is more expansionary than it actually is.

But in terms of ordering the degree to which nations engaged in fiscal stimulus the structural balance (properly measured) is a much more reasonable measure than that used by Dr Laffer in his table.

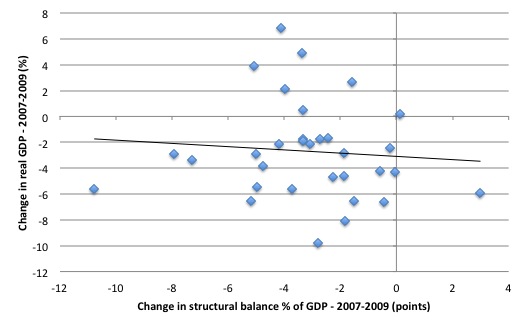

Accepting the limitations of the IMF structural budget measure, I reconstructed the Laffer Table. Given the budget measure has already been cyclically decomposed (limitations notwithstanding) we can relate that to the more intuitive measure of expansion in economic activity (real GDP growth) rather than the change in the growth rate that Dr Laffer uses as a dodge.

The following graph shows the ordering for the OECD nations (minus Mexico and Estonia for which no budget data is available from the IMF) with the change in the structural balance between 2007 and 2009 (in percentage points) on the horizontal axis and the change in the real GDP growth rate between 2007 and 2009 (ignoring the points above about lags)

The Table is the data. The relationship is as expected – an increase in the structural budget balance leads to higher real GDP growth – the opposite conclusion being argued by Dr Laffer. Further, if we take Iceland out of the Table (as a clear extreme value) then the relationship gets steeper.

If we used a more exact measure of the discretionary budget stance (given the IMFs measure still contains some cyclical effects) then the relationship would be even clearer.

I produced other graphs and tables for a number of different time periods and the conclusion doesn’t alter. One graph shows that tax revenue is inversely related to both the change in real GDP growth (Dr Laffer’s measure) and real GDP growth. From which Dr Laffer would conclude that tax cuts are bad for growth. Of-course, the cyclical effects are driving that relationship.

Conclusion

That is all I have time for today. As the Guardian article noted – a comedian.

But comedians are better being funny rather than tragic. At least Dr Laffer no longer has the traction in the policy debate that he had when he influenced Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s.

Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally

My Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally is now active.

I update it early in the day and again around lunchtime when all the sports are concluded for the day.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I well remember when “voo-doo” economics was being foisted on us. What amazed me was that people who were never intended to get tax cuts thought Regan was going to cut their taxes and later remembered that he did so. But, they never remembered the tax increases that Regan did give them. I am still amazed by how people remember Regan. In my mind there is a difference between ignorance and stupid and I must say that a lot of the people I knew back then were just plain stupid. I liked them, but they were stupid.

But, your quote that Laffer made shows why people were so stupid. When Laffer said, “government taxing people more who work and then giving more money to people who don’t work is a surefire recipe for less work, less output and more unemployment,” he was playing to bigotry and trying to divide working people against welfare people. In other words he played the race card the same as Regan did when he railed against welfare queens. I am afraid that Romney is doing the same thing now when he says that we should make welfare recipients work. I know bigots on government assistance that will vote for that because they are white and consider that only blacks and Mexicans get welfare. Talk about cutting your nose off to spite your face.

I want to point out that I am all for your jobs guarantee, but I don’t think that that is what Romney means.

The Laffer curve is valid or invalid depending on exactly what your definition is. If the definition is confined to the idea that the higher the rate of tax, the more effort is put into tax evasion, then that idea is probably valid. (And that’s what I always understood the term to mean.) And the net result might well be that at very high rates of tax, very little revenue will accrue to government.

But of course Dr Laffer’s other points (some of them purely political) about the evils of high tax rates are hogwash and Bill rightly points out.

In debates on taxes I think it is crucial to consider the nature and effects of different taxes. Not all taxes are equal and they shouldn’t just be lumped together as “tax rate”. As an MMT advocate you should be pushing the fact that taxation policy is more about controlling agregate demand than raising revenue. In this respect we need to be looking at how fiscal policy encourages or discourages certain types of activity. Clearly pay-role taxes verses pollution taxes have differing influences on an economy and one (in my opinion) is more justifiable on both an economic and an ethical level.

So it is not just about *how much* we should be taxing it is more about *what* we should be taxing and how we allow and encourage people to gain incomes. It is clear to me that the big problem with the highest earners pulling away from the rest and increasing income inequality, is that in general, the richest gain their income from *rents* rather than *productive work*. And by and large most fiscal policy targets productive work rather than rents (particularly those of the finance sector).

” If the definition is confined to the idea that the higher the rate of tax, the more effort is put into tax evasion, then that idea is probably valid”

it’s not though is it. It’s a classic excluded middle logical fallacy – because you’ll get that sort of thing at very high rates of taxation its best to cut rates to next to nothing.

Bill Mitchell

Then the implication is that paying off the National Debt (of a monetary sovereign) with new reserves would not cause significant price inflation? Then why not do it (as the debt comes due) and remove the confusion about deficit spending?

Neil, The standard Laffer curve (on my definition) is a classic example of an idea which DOESN’T fall for the “excluded middle”. Look at the chart half way down Bill’s post: it shows revenues at a MAXIMUM when taxes are somewhere in the “middle”.

What if we had coexisting government and private money supplies? Then price inflation in the public and private sectors would be separate issues, no? And each sector could mind their own business wrt money creation? So taxation policy would be greatly simplified?

Moreover, with genuinely separate government and private money supplies then government deposit insurance and a lender of last resort would no longer exist. That means that ONLY government money would be 100% risk-free. That risk-free advantage could be used to generate large revenues (aggregate demand reduction) for government, perhaps to the extent that Federal taxation could be eliminated or at least greatly reduced?

Supply-side economics is a cult based on value perception. It conflates savings with investment when no relationship exists. Investment is a slang term that implies spending on an asset vs a liability. The asset can return earned income or unearned income. Unearned income is a tax on growth, a tax on labor’s surplus, a type of wealth transfer. Laffer implies that all savings is invested productively. Most savings are pooled and seek returns of unearned wealth which is distributed to a fortunate few. The pool itself may become the target for returns of unearned income.

F. Beard What if we had coexisting government and private money supplies?

No law against free banking in the US as far as I know. Anyone can lend their own IOU’s, but as Minsky observed, the trick is getting one’s IOU’s accepted.

The reason that there is no free banking to speak of in the US is that it can’t compete against the public-private partnerships having advantages like a currency-based interbank settlement system, LLR, and FDIC. Why would anyone accept bank iou’s instead, where the risk is higher and the convenience less.

Of course, banks could also issue fixed weight token of PM’s, offer a true bullion standard, and lend in terms of it. So far no one has seen a way to profit from it.

F, Beard Then the implication is that paying off the National Debt (of a monetary sovereign) with new reserves would not cause significant price inflation? Then why not do it (as the debt comes due) and remove the confusion about deficit spending?

Because this would draw down non-govt saving in net financial assets. The ratio of public debt, really saving of NFA by non-govt, and private debt needs to be high enough to offset the exposure to the downside of leverage that private debt presents.

Presently, the ratio is too low, which means that there is too much private debt in the system for safety. The system is now trying to self-correct by delevering and increasing savings while the govt is pursuing a policy of austerity. Instead, govt needs to be expanding non-govt saving of NFA as a “macro-prudential” measure. Otherwise, the US is moving toward a fiscal cliff with increasing austerity in the face of a persistent CAD and still elevated private saving desire.

Of course. And a shorter description of “public-private partnerships” is fascism. Our money system is fascist.

PMs as money are dumb. Common stock is a much more sensible and ethical private money form that requires neither fractional reserves nor usury.

Because of the usury paid. But that’s not a problem since a monetarily sovereign government can always increase spending in other areas to compensate. And since the usury paid often goes to the rich, a national debt is not only confusing but fascist too.

The diagram that puts the maximum tax receipts somewhere around a 50% tax rate ~ somewhere “in the middle” ~ that’s a substantial part of the deception of the Laffer curve. Suppose that the Laffer curve is “formally true”, but the maximum tax receipts are at a 90% or a 95% tax rate. Then it would turn out that all of the policies which follow from the Laffer curve as Laffer originally drew it on a serviette don’t, in fact, follow.

.

A second bit of deception in the 1980’s was to conflate marginal tax rates before income tax loopholes and average income tax incidence.

“Neil, The standard Laffer curve (on my definition) is a classic example of an idea which DOESN’T fall for the “excluded middle”. Look at the chart half way down Bill’s post: it shows revenues at a MAXIMUM when taxes are somewhere in the “middle”.”

It does because the extreme argument at the edge of the curve is used to justify the shape of the curve. Even though emprically it is completely the wrong shape. It has to be or the UK’s tax credit clawback mechanism – where marginal rates are in excess of 70% – wouldn’t work and that would show up in the tax collection data.

I did see research somewhere where they show that empirically there is little tax effect on rates less than 70% and then a sharp drop off. So not really a curve at all – more a cliff edge.

I’m an amateur just learning about MMT. This discussion is fascinating. Is it too obvious to point out that the real actors in our political theater will champion almost any silly economic idea (Ivy League provenance helps) that furthers their ends? They don’t care whether it’s true or not. In fact, deception may be the whole point. As more thoughtful people spend time debunking and deconstructing their phony idea, they’re probably having as good a laugh as the Greeks had watching the Trojans try to interpret the meaning of that big wooden horse.

surely as higher rates of income tax fell

deposits in tax havens grew?

surely a far more logical and empirically accurate theory

people try to minimize their tax burden

those on PAYE have no opportunity to do so

if the ability to avoid taxes outstrips the ability to collect taxes tax- evasion grows

the tax evasion industry is better resourced than tax collection

if you choose to avoid paying taxes and can achieve that aim you would regardless of the rate

0% is your desired outcome

mr Carr managed 1%

“Tom Hickey says:

F, Beard Then the implication is that paying off the National Debt (of a monetary sovereign) with new reserves would not cause significant price inflation? Then why not do it (as the debt comes due) and remove the confusion about deficit spending?

Because this would draw down non-govt saving in net financial assets.”

Not really. Reserves are financial assets too so it would be mere asset swap. I think it would be sensible thing to do just because so many people think bond sales limit government’s ability to spend.

PZ, I was assuming that F. Beard wants to redeem tsys as they come due and run a balance budget so that no new tsys are issued, thereby “paying down the national debt.”

I am in agreement that ending the process of money creation through the façade of tys issuance corresponding to currency issuance by the cb is a good move, but not that the govt run a balanced budget, too.

Under a no tsy issuance policy, the cb would have to use IOR as the tool if wished to set the rate above zero, instead of OMO.

However, there are banking issues related to a no tsys policy that Warren Mosler has proposed to avoid by limiting tsy issuance to 3 mo. bills max and providing them as demanded rather than as a required deficit offset.

I distinctly said “with new reserves.” That implies, I thought, a budget deficit.

For the record, I think a monetary sovereign should ALWAYS run a deficit (without borrowing, of course). However, some years the deficit might be very small to allow the real economy to catch up to the money supply should the government overshoot with reserve creation.

After the latest screw up by the banks we should be seeking ways to reduce banking to insignificance rather than ways to accommodate it.

PZ: I think it would be sensible thing to do just because so many people think bond sales limit government’s ability to spend. Right, the main thing is to educate people to not support economic policies that cut their own throats. If a no-bonds / ZIRP helps do that, having one for a decade or a generation until everybody gets educated in real economics would be well worth it, even if it were determined that a different, more active monetary policy would be better.

Laff-In: Here is a completely accurate picture of the Laffer Curve, drawn by the late Martin Gardner for his article on it.

Neo-Laffer Curve

Prof Mitchell:

Your Fair Economy link is outdated. Here’s the updated one:

http://www.faireconomy.org/trickle_down_economics_four_reasons

I heard Bill Black today talk about Arthur Laffer, and decided to turn to your blog for information. Always above & beyond the call of duty~! [-]