I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When politicians stop an economy from growing

Yesterday I raised the issue of the dysfunctional political situation in the US which is preventing the US President from introducing a public works program aimed at boosting the degenerating public infrastructure. The fact that such a policy could generate millions of jobs and improve the long-term productive capacity of the nation is unquestioned. It was suggested that the US President might offer the conservatives widespread deregulation which would cut wages as a compromise. This would be pandering to their erroneous claims that that supply-side factors are restraining the capacity of American businesses to create work. Today we examine some recent research evidence that demonstrates how far amiss the current policy debate is. The evidence shows that firms are constrained by lack of spending at present and that the private sector is in a vicious cycle of spending paralysis. It suggests that the only way ahead is for the government to increase aggregate demand (via fiscal policy) but that the ideological obsession of the elected politicians is blocking the only growth option currently available. We are in a state where our politicians are deliberately stopping the economy from growing.

There was an interesting research paper published recently (July 21, 2011) by the US Federal Reserve Bank of New York – Why Small Businesses Were Hit Harder by the Recent Recession – which is part of its Current Issues in Economics and Finance series. I was initially interested in it because I have done a lot of work in the past on the role of firm size in job creation and job destruction rates. Specifically, I have been interested in the popular view that small business is the dynamo of advanced economies – which feeds into the debate about the impact of regulation and employment protections on employment.

My work which resonates with other international studies suggests that small businesses do not generate the most jobs and that the impact of legislation pertaining to job security and redundancy protections etc do not impede employment growth. But that is another blog.

The NY Federal Reserve paper mentioned above is less about those issues and more about the cyclical impacts on firms by size. So that is another interest of mine – how do economies adjust during a cyclical downturn?

The Paper begins by noting that:

The recent economic downturn saw an unprecedented deterioration in labor market conditions. From the December 2007 start of the recession to December 2009,1 nonfarm payroll employment-the traditional measure of U.S. jobs – declined by 8.4 million, a drop in levels unmatched in the entire postwar period. A closer look at the employment figures reveals that the recession’s effect has not been uniform across firms of different sizes: small businesses have in fact been more adversely affected than large ones. Jobs declined 10.4 percent in establishments with fewer than fifty employees, compared with 7.5 percent in businesses with fifty-plus, while overall employment decreased 8.4 percent. This pattern is noticeably different from the trend of the 2001 recession.

Given that finding the Paper aims to “shed light on some of the factors that caused small businesses to be hit harder than large firms during the last downturn.”

So that is an interesting research exercise and they conduct a large national survey of businesses and combine the results with several other publicly-available datasets. The details of the data and the survey sample are outlined in the Paper and I won’t go into them here.

The NY Federal Reserve Paper considers two supply-side explanations for the “recession’s disproportionate effect on small firms: sectoral composition and credit availability”.

The sectoral composition hypothesis says that “if employment declines relatively more in sectors populated with small firms” then “in the aggregate these firms could account for a higher percentage of job losses”. The evidence fails to support his hypothesis – small firms in all sectors were “hit harder than large ones”.

They also find that “limited credit availability” was of secondary importance in explaining the difficulties faced by small firms.

Overall they say that:

… demand side factors – notably, economic uncertainty and poor sales stemming from reduced consumer demand-appear to be the most important reasons for the relatively weak performance and sluggish recovery of small firms.

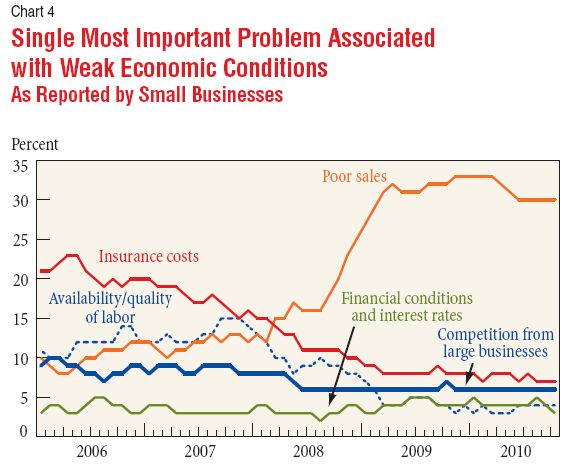

The following graph reproduces the NY Federal Reserve Paper’s Chart 4 and it shows the various assessment of the factors that small businesses considered impacted on their performance. The authors say that “owners of small businesses are regularly asked to identify the most important problem associated with weak economic conditions”.

The result is stark and shows the increasing impact of aggregate demand as the economy contracted and unemployment rose.

The deficient aggregate demand creates a vicious cycle. The NY Federal Reserve paper concludes that the evidence shows that:

… the chief reason for their sluggish performance appears to be a lack of current and expected future demand for their goods and services, as reflected in the firms’ concerns about poor sales. This reduced consumer interest in the products of small firms likely lowered the firms’ demand for credit. In these scenarios, firms do not have the ability to invest and thus have little need to borrow.

From which we understand that the constraints are not emerging from the financial system (liquidity constraints etc) but from the lack of aggregate demand – which in turns reduces the need to invest which reduces the demand for credit.

The final question of interest (that you might like to know about) is why did small business suffer more this time than big business?

The answer is not straight forward but the NY Federal Reserve paper suggests that sales growth recovered earlier for the larger manufacturing firms “while sales of small firms have lagged and their recovery has been sluggish”. Further, the inventory cycle has been more severe for smaller firms such that “small businesses managed the fluctuation in sales through greater inventory adjustment”. In other words, the larger firms seemed to start producing inventory replacement earlier than the smaller firms.

But overall, the reason the “downturn has had a deeper employment impact on small businesses than on large ones” is because the “poor sales and economic uncertainty” have impacted more severely on the smaller firms.

The Paper however, doesn’t provide a detailed explanation for why that would be the case and so I suggest a PhD student could write a very good thesis exploring that topic.

The facts are there – small businesses suffered disproportionately. The link between aggregate demand and employment growth is also clear. The research question is why did aggregate demand fall more sharply for smaller businesses.

The results call into question those who have been arguing that monetary policy is the only show in town.

This research also resonates with a recent New York Times article (August 16, 2011) – It’s the Aggregate Demand, Stupid – which was written by a former senior policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and George Bush (senior) – one Bruce Bartlett.

Given he has also served on the staff of Ron Paul I was wondering what the article was to be about – apropos of the title.

Well it couldn’t be more clearly expressed:

With the debt limit debate temporarily set aside, the Obama administration is talking about finding some way to create jobs and stimulate growth. But the truth is that there really isn’t much it can do and it knows it. There may be some small-bore things it can do without Congressional action that may help a little, but the operative word is “little.” The only policy that will really help is an increase in aggregate demand.

Aggregate demand simply means spending – spending by households, businesses and governments for consumption goods and services or investments in structures, machinery and equipment. At the moment, businesses don’t need to invest because their biggest problem is a lack of consumer demand …

The federal government could increase aggregate spending by directly employing workers or undertaking public works projects. But there is no possibility of that given the political gridlock in Congress and President’s Obama’s desire to appear moderate and fiscally responsible going into next year’s election.

That really leaves just consumers as a potential avenue for increasing spending. But that will be difficult as long as unemployment remains high, thus reducing aggregate income, and households are still saving heavily to rebuild wealth, which was decimated by the collapse in housing prices. Saving is, in a sense, negative spending.

So three points are clear:

1. There is not enough spending in the US at present and that is why there is high unemployment and stagnating growth.

2. The components of aggregate spending are obvious – and an examination of them reveals that non-government spending is not going to grow fast enough to stimulate the economy largely because firms are constrained by lack of consumer demand which is being driven by entrenched unemployment.

3. The only way out is for public spending to increase – “by directly employing workers or undertaking public works projects” – but that won’t happen because the “political” situation will not allow it.

The evidence is very clear – the politicians are deliberately undermining the growth of the US economy.

This insight is obvious to anyone who understands the economics of the situation – and that doesn’t include the majority of my profession which prefers to promote their ideological dislike of public activity ahead of an appreciation of the research evidence.

The challenge is to get that message out into the public domain so that the political debate changes and the artificial restrictions on fsical policy that are undermining growth and prosperity are lifted and national governments get back to doing what they were meant to do – pursue public purpose and sustain full employment.

There was a related New York Times (August 24, 2011) – How Much More Can the Fed Help the Economy? – where we read that there is little that the US central bank can do with monetary policy to provide the necessary stimulus to US growth.

The author (Catherine Rampell) concludes that the Federal Reserve is the only policy arm of government that has room to move because:

After all, Congress seems wholly unwilling to engage in fiscal stimulus, and instead is planning further fiscal tightening.

Once again you understand that it is not a problem of fiscal effectiveness but the politicians who have to act to use the fiscal tools.

Rampell however believes that “the Fed’s remaining tools may be losing their potency” to which I would say when did they ever have any potency.

She understands that monetary policy works via interest rate movements and that cutting interest rates provides a “good opportunity to extend more loans. If more loans go out to people and companies, those people and companies can buy more goods and services, creating more demand and eventually more jobs”.

Quite apart from whether monetary policy works, what you understand here is an emphatic statement that aggregate demand (however originated) stimulates production and jobs.

But the proposition is that with interest rates “already at zero” and quantitative easing not appearing to have stimulated borrowing (despite holding down long-term interest rates), there is little the Federal Reserve can do.

She suggests there is political pressure on the central bank not to expand its balance sheet further although there “would probably be less political resistance to reconfiguring, rather than expanding, the central bank’s debt holdings” – that is, purchase debt further out on the yield curve (longer maturity assets) which might lower long-term interest rates.

It is clear from the NY Federal Reserve paper that there is little demand for credit at the moment for the reasons discussed. So it is not about price but poor expectations of future revenue streams that is driving the flat demand for loans.

She says the central bank “could also lower the interest rate it pays banks on their reserves” and “(m)aybe this would encourage them to hold less cash and increase their lending” but in saying that she falls into the trap of thinking banks lend out reserves. They do not need the reserves to lend. Their capacity to lend is not enhanced by the reserves they are currently holding.

Her concluding suggestion is that the central bank should announce “that it is raising its medium-term target for inflation” which might bring forward consumption and investment decisions (because people would be worried that prices would rise) and also deflate current debt burdens. These real balance effects are likely to be very small indeed and are not a credible way to promote higher economic activity.

The fact that people are still harking after the central bank to cure this impasse is a reflection of the ideological bias against fiscal policy which is promoted by mainstream economists.

The crisis has emphatically taught us that monetary policy is a largely ineffective policy tool to counter-stabilise negative demand shocks. It has also taught us that while economists eschew the use of fiscal policy and dismiss it as being ineffective and inflationary, the fiscal stimulus interventions of governments all around the world helped consolidate aggregate demand and restore growth. In the same way, the fiscal contractions are pushing economies back into the red.

Conclusion

The message is simple – aggregate demand has to rise for there to be serious job creation.

That requires spending and at present the private sector is stuck with low confidence and high debts. There is only one solution and the politicians that have been elected are failing in their duties to increase the welfare of their nations.

That is the message that should be getting out – get rid of politicians that deny the obvious – just because they hate public activity. At present, whether you hate it or like it, increased public spending is the only way out of this crisis in the coming months. Putting political constraints on fiscal policy is tantamount to admitting that you want more citizens to be unemployed and more firms (particularly small businesses) to go to the wall.

Why don’t the Texans etc tell that to their Tea Party supporters – as they put their hands on their hearts and feign a devotion to matters spiritual including integrity and honesty.

That is enough for today!

Admittedly, I know practically nothing about economics, but the Federal Reserve Paper cited by Bill doesn’t strike me as entirely convincing, particularly the argument that there were no important supply side factors differentiating the impact of the downturn on small and large business.

The first reason why I’m not convinced is that the source of the analysis is typically ‘bank-friendly’ in its point of view. Now one difference between small and large businesses is i.i.r.c. that the former are more dependent on bank credit and loans than the latter. All business have overheads irrespective of sales, and they can’t all be trimmed by shedding labour, even in the US. So in a downturn, businesses experience cash-flow stress, and become more dependent on their creditors to overcome this situation temporarily. The situation is i.m.h.o. more pronounced for small businesses. But looking at the graph provided there isn’t even a blip in the ‘financial conditions and interest rates’ time series. Which is the second reason why I don’t find the paper convincing.

Obviously, the main reason for the GFC was lack of demand. But to me, the hidden message of this research paper is ‘the banks are not to blame’.

Sorry for submitting two comments in a row but I’d like to point out something about the Bruce Bartlett quote, which you summarize as:

3. The only way out is for public spending to increase – “by directly employing workers or undertaking public works projects” – but that won’t happen because the “political” situation will not allow it.

I’ve seen this sort of comment a lot recently and one thing that isn’t clear is how much it is a positive and how much a normative statement. In other words the commenter is really saying – spending can’t be increased for political reasons so don’t even think about it.

Bill,

I think you forget that there already was a stimulus (fiscal+monetary) and that did not increase aggregate demand. What makes you think that another bout will work?

The news media has drilled into everyones head that the government has run out of fiscal space and that they emptied the chamber on the first stimulus. This is quite the concerted attack!

Sean,

The stimulus put forward in the US was, by most accounts, far too small to have a substantive and long lasting effect: less than 800 billion USD with about 40 percent of that in a tax cut. From what I have seen, this did raise aggregate demand; however, as the effects of the insufficient stimulus have given way, so has the increased aggregate demand.

Sean:

Don’t tell me it didn’t increase AG. My business got an upturn that started in early 2010 and now everyone is waiting to commit to any additional projects. I confirmed this anecdotal data point with multiple colleagues. It was enough of a stimulus to continue to muddle through, whether by design or political compromise. It needed to be about 2.5x as large.

Bill, I am a non-economist trying to learn/understand MMT, and I frequently have problems due to lack of knowledge. this morning I have read a few articles that tie to some of your writings, the second one following specifically to this column. I would like to ask you to expound on and clarify these articles in the light of MMT.

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2011/08/24/661146/an-important-lesson-from-jackson-hole-2010/ This seems to be consistent with MMT, and could be a sign that others are catching on. Could one say that a major part of the economic malaise is solvency rather than liquidity?

How would that tie in to the liquidity trap as presented here and

how does MMT address the liquidity trap as presented here? http://newmonetarism.blogspot.com/2011/08/liquidity-traps-money-inflation-and.html

Change of subject. You have asked MMT doubters to explain the Japan situation. How do these 2 articles tie into the MMT perception:

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2011/08/23/659926/against-japan-ification/

http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/6895

The second one seems to throw something of a new light on Japan, but I can’t relate it to MMT without some help.

Sean,

The monetary stimulus (lowering the interest rates) indeed didn’t work: people are saving instead of leveraging up further. That is a good thing. Other monetary “stimuli”, like swapping bonds for reserves are hadly stimulatory, if you know how these things work.

Fiscal stimulus always raises spending, dollar for dollar. It is math, not a theory. So if you increase spending by 5% of GDP and GDP goes down 1%, it just means that without the stimulus it would be down 6%. You might say the stimulus didn’t work, but that is a really strange definition of “work”.

Bill et al.

I have heard that in the UK banks are allowed to off-set the writing-off of bad debt against their Corporation Tax, which is why the banks in the UK have been paying no tax since the start of the recession. Apparently, most of the collapse in tax revenue can be attributed to this.

If true, this is another example of the automatic stabilisers in action, and is a very good argument against the Austrians who seem to have no dificulty allowing ordinary people, and otherwise sucessful businesses to go bust as a result of insufficient aggregate demand. They just need to understand how increased bad debt feeds back into reduced tax revenue.

I have an accounting question.

When the gov’t spends, it markups the demand deposit account of the recipient and markups the reserve account of the recipient’s bank 1 to 1. If a bond is sold, the buyer’s demand deposit account is marked down and the reserve account of the buyer’s bank is marked down 1 to 1. First, is that correct?

Next, when private debt is created, the demand deposit account of the recipient is marked up, HOWEVER is the reserve account of the recipient’s bank marked up 1 to 1? Lastly, the loan is “attached”. It seems to me the demand deposit and loan are created near simultaneously.

Thanks!

There’s a lot to be learned by looking at Japan’s experience; monetary policy failed, but fiscal policy did help a great deal. I’m reading Richard Koo’s book, “The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, Revised Edition: Lessons from Japans Great Recession”. This should be required reading for all members of Congress. Then again, large numbers of our Congresspeople appear to be illiterate.

I have long been a convinced supporter of Keynesian economics and government economic stimulus during recessions. I believe the historical record shows it worked admirably post WW2. MMT takes Keynesian theory to its logical and empirically validated conclusion. However, two problems remain. One, is that neoclassical economics and ideology remain dominant and there seems no way to dislodge it. The second problem pertains to growth in a finite world that imposes limits to growth.

Bill Mitchell writes, “It suggests that the only way ahead is for the government to increase aggregate demand (via fiscal policy) but that the ideological obsession of the elected politicians is blocking the only growth option currently available. We are in a state where our politicians are deliberately stopping the economy from growing.” But does Bill Mitchell recognise that the economy cannot keep growing indefinitely on a finite planet? Does Bill’s version of MMT recogise that eventually a steady state economy with a steady state population and fully reneweable cycles of resource use must be achieved?

Dear Ikonoclast (at 2011/08/26 at 7:13)

You ask:

Bill Mitchell does recognise that.

Bill’s version of MMT does recognise that.

best wishes

bill

Thank you Bill. Can you link to some MMT analysis of limits to growth and sustainability issues? As an intelligent (I hope) and questioning citizen, I always regard it as my duty to ask the potentially awkward questions. I have found that blindness or over-optimism regarding limits to growth issues extends beyond neoclassical economics and into the thinking of a number of otherwise enlightened economists.

I see thermoeconomics or biophysical economics as an emerging discipline with a lot to say on the issues of limits to growth and sustainability. This is not to say that I see thermoeconomics supplanting Keynesian-MMT analysis. Rather I see it as supplementing it. Money flows in the economy (and the attendant class and ideological battles) need to be understood and analysed correctly within political economy. Equally, energy and material flows between the environment and the economy need to be analysed empirically. Properly understood, the human economy is a sub-system of the total environment and totally contingent upon it.

A persistent modern myth is that human intelligence, ingenuity and the development of technology will allow us to transcend natural limits. Specifically this would mean breaking or obviating the laws of thermodynamics. As a shorthand, I always say we can stretch the natural limits but we can’t break them. Stretching always implies a snap-back (or a breakdown) when the limits are reached. Francis Bacon, arguably the instigator of empiricism and the experimental method, states in his aphorisms;

“Human knowledge and human power are one; for where the cause is not known, the effect cannot be produced. Nature to be commanded must be obeyed; …”

and again;

“Towards the effecting of works, all that man can do is put together or put asunder natural bodies. The rest is done by nature working within.”

These are profound words and whilst arising, in some respects, from a religious and metaphysical view which no agnostic empiricist would now accept, they do convey precisely man’s position as whoolly enmeshed in and contingent upon the totality of natural forces which constitute the known universe.

I’m pleased Bill Mitchell recognises the economy cannot keep growing indefinitely on a finite planet…..Personally I never doubted Bills intentions in this regards.

I’ve noticed on forums a growing number of people supporting austerity measures as a means to reduce consumerism and waste of precious resources. These people are critical thinkers and may not be natural supporters of mainstream neo-liberal economic arguments. We need to have some of these people on board the MMT train.

I’ve noticed Neil Wilson and a few others proposing expansion of a “non profit” service based economy as a means to generate economic growth without excessive consumption. This requires the shackles being taken off Governments fiscal spending capability. People providing useful social services still need the means to acquire food, shelter transportation and a little bit of bling now and again. The providers of economic necessities need investment to make them more sustainable and energy efficient. Wasteful luxury items need to be taxed at ever higher rates.

I guess it’s not essential for sustainability policy to be incorporated into MMT economic policy. Mind you, sustainability policy is definitely absent in most mainstream economic policy. It could be a good selling point for MMT.

Fed Up,

The balance sheet accounting is as follows (from the private bank’s point of view where customer deposits are bank liabilities)

Bank Reserves, Cash, Loan Advances and Investment Assets are bank asset accounts

Customer Deposits and Investment Assets Pledged are bank liability accounts.

Private Loan advance

DR Loans Advanced, CR Customer Deposits

Private Deposit payment to recipient at same bank

DR Customer Deposits, CR Customer Deposits

Private Deposit payment to recipient at different bank

DR Customer Deposits, CR Bank Reserves

Private Deposit payment to central bank for a bond

DR Customer Deposits, CR Bank Reserves

Bank purchasing central bank bond on own behalf

DR Investment Assets, CR Bank Reserves

Private Deposit receipt from different bank

DR Bank Reserves, CR Customer Deposits

Private Deposit receipt from central bank (social security payment, etc)

DR Bank Reserves, CR Customer Deposits

Bank using bonds to borrow reserves

DR Bank Reserves, CR Investment Assets Pledged

Bank interest charge

DR Customer Deposits, CR Bank Income

Loan capital repayment

DR Customer Deposits, CR Loans Advanced

Cash Transactions (sold for bank reserves except for the necessary float)

DR Cash, CR Whatever

DR Bank Reserves, CR Cash

HTH

NeilW

@Ikonoclast: I’ve been thinking the same thing, about how to combine an ever-growing economy within a limited world. That is indeed not possible, if you assume the economic growth is in the same “category” as it currently is. Meaning, ever growing world population, buying more and more stuff and using more and more (non-renewable) energy.

However, if you think about what economic growth is: it’s mostly a growing amount of money going around, used for a growing amount of “activity/resources”. It is not necessary for that economic activity to equal pumping up oil and making single-use plastic junk out of it. It could also be a better kind of activity. Teaching, reading, providing services, human activities: potentially very valuable things, but not necessarily needing lots of non-recyclable natural resources. We in the western world really have enough food and material (even though it’s not distributed well). In a couple of decades it should be possible to build enough wind farms and other cleaner energy resources to provide plenty of energy. After that, what “we” “do” in economic terms, is all luxury. The times of driving around for fun in a 4by4 hummer, burning up massive amounts of oil are probably over. But I don’t see why doing something else wouldn’t be just as valuable.

Of course, in the near future economic growth will go hand in hand with more wasteful use of energy and natural resources. Hopefully it will be turned around soon enough.

Neil Wilson’s post said: “Fed Up,

The balance sheet accounting is as follows (from the private bank’s point of view where customer deposits are bank liabilities)

Bank Reserves, Cash, Loan Advances and Investment Assets are bank asset accounts

Customer Deposits and Investment Assets Pledged are bank liability accounts.

Private Loan advance

DR Loans Advanced, CR Customer Deposits

Private Deposit payment to recipient at same bank

DR Customer Deposits, CR Customer Deposits”

For example, I go get a mortgage at a bank. The bank markups my demand deposit account and markups their loan account (assets). When the bank markups my demand deposit account, there is no 1-to-1 (central bank) reserve account markup at the same bank. Correct?

Also, if the federal gov’t deficit spends then my demand deposit account could be marked up. If so and when the federal gov’t markups my demand deposit account, there is a 1-to-1 (central bank) reserve account markup at the bank where my demand deposit account is located. Correct?

Ikonoclast, I think MMT doesn’t confront with thermodynamics and actually can be used to shape the system into a sustainable path. I would like more academic activity on this front from heterodox economists (I agree is a raising field) also centring on quality of ‘growth’ instead on quantity, but most heterodox are too busy fighting mainstream non-sense.

First, growth gets confused a lot and does not necessarily mean increasing output of goods, but it’s unquestionably related to this, specially on developing (non-postindustrial) nations. Also, continued production means consuming natural capital, this means that growth is not the only problem, but maintaining a steady-state (now growing) economy could too pose a problem on the “long” run, if not enough progress is made on the current industrial, logistical and consumption models (all tied with urbanism, efficiency on reduction of waste in the industrial process, etc.).

But let’s see: increasing demand and achieving full employment would signal the right prices on commodities, without needless credit expansion. Increasing net financial assets, without debt from the public and letting it circulate through the economy, and eliminating “speculative stocks of money” (overextension of financial sector, inflated by credit expansion in the last decades) would tell us the right prices for the current demand/offer on natural capital. Increasing net financial assets would trim out most of debt expansion necessity, which in the end only means we have to produce and consume more to pay debts; so functional finance can be used to lessen the burden of debt and by extension, unnecessary economic activity.

Instead we can centre on quality “growth”, the sort of growth that does not mean increased goods production. Or forget the growth mantra and see how we can achieve a stable secular deflating economy (demographics, biophysical and resources decline) instead of an unstable one which lead to social instability, inequality and ultimately to violence and poverty.

I think through understanding money (I don’t agree with the adjective “modern”, because for the most part of history the monetary systems where like the current one, not gold-standard) system we can forget about non-existing “financial problems” and watch out for the real thing: the only constraints are real.

So:

1) Reduce debt burdens is a necessary steep to a steady-state economy.

2) Reform of financial subsystem is also a necessary steep: reduction of dependency on credit expansion, reduction of cumulative stocks of money which increase price volatility and instability, which is the end does not help solving the real problems.

3) The only way to have a steady-state economy is to have an stable social fabric, so we can do this while maintaining some sort of social equality and quality of life, instead of the usual suspects for solving this: violence, war, poverty and marginality, etc.

It’s all about money system and political system, we can have democracy and progress or at least a sustainable society. Certainly big ancient civilizations were stable for thousands of years as long as exogenous shocks -natural constraints or external forces- didn’t finish them, in my opinion we haven’t crossed the point of no return on natural capital. So the rest lies in us.

An observation and a comment. All of the countries in the Eurozone are taking the path of austerity- reduced govt. spending, because they are confronted with the consequences of the loss of investor confidence (higher cost of debt). Germany has a balanced budget amendment, and other countries are moving toward that. So why do Keynesians believe that the U.S. can spend into oblivion without said consequence? Maybe because we can devalue our (the worlds’) currency? Given the inability of politicians to address the structural imbalance between entitlements and our ability to pay for them, this means either one of two things…extreme inflation or higher taxes, or both. Although I also argue that the efficiency of government spending is poor relative to that of the private sector, there must be progress towards resolving the entitlement issue before the public will endorse wanton higher levels of debt!!! BTW, govt. spending IS increasing, from $2.9 trillion in 2007 to $3.8 trillion in 2011, to $5.4 trillion in 2020. But less of the spending is discretionary, because…….