I am still catching up after being away in the UK last week. I will…

Australia’s great productivity slump – what else would we expect!

Today I got around to reading a report – Australia’s Productivity Challenge – which was released last week (February , 2011) from the Grattan Institute, a new research organisation in Australia that aims to provide evidence-based insights into social and economic issues in Australia. The Report is interesting because it exposes some of the bigger lies that are abroad about how well the Australian economy is faring. I have consistently been arguing (over the last 15 odd years) that the neo-liberal policy onslaught that has aimed to erode the power of workers viz capital and create a desperation among the unemployed (making income support harder to get) have created a dumbed down economy – racing to the bottom. One manifestation of this prediction was that productivity would fall as the impact of the budget surpluses (reduced public investment) and legislative changes too their toll. The Report shows that this future is upon us – we are living a delusion – being propped up by China. That is not a sustainable future.

On August 12th, 2009, I wrote the following blog – Dumbed down economy doesn’t lose as many jobs – for more discussion on this point.

The Report is relevant for many strands of the current policy debates. It bears on the so-called intergenerational debate where supposedly budget deficits will become unsustainable because of the ageing society. I note that this debate resonates in discussions across all nations where the proponents of austerity are attacking social welfare, health and pension systems on the basis of alleged public sector insolvency.

I have previously written about the flawed reasoning underpinning the mainstream arguments in this debate. Please read my blogs – Democracy, accountability and more intergenerational nonsense and Another intergenerational report – another waste of time – for more discussion on this point.

It also bears on debates about labour market deregulation – which accompanies the flawed macroeconomic arguments that underpin the austerity drive. Apparently, labour markets are sclerotic because workers are too generously compensated (particularly public servants so the narrative runs) and will have to take significant cuts to provide firms with incentives to increase employment. Part of this narrative runs into the public sector insolvency stories as well – that the state has run out of money and cannot carry the wage bill any more.

Further, we are being told continually by the federal government that they have to get the budget back in surplus because the economy is going along so strongly and the mining boom will see us living in clover. This particular debate is reaching comical proportions at present. Given the devastation across our landscape at present – very severe floods in the Eastern states (and in the North West); a category 5 cyclone creating havoc in Far North Queensland the other day; out of control bushfires in Perth at present – one would not be expecting a serious political party to be advocating cutting a pitiful amount of foreign aid to the poorest nations in Africa to “pay for” the reconstruction.

But that is what the federal opposition are currently arguing. Their conservative hearts have shrunk a bit and they think a wealthy country like Australia with a sovereign government that has no financial constraints cannot afford to feed some starving kids in Africa because we need to rebuild some damaged infrastructure in Queensland.

They claim there is a shortage of workers yet at present 12.5 per cent of available labour is idle (unemployed or underemployed). The reconstruction effort is ideally suited to absorbing this predominantly low-skilled labour and the work is definitely localised in heavy population regions (for example, Brisbane) so there shouldn’t be any problems matching labour to work.

The Government is just as bad – maintaining that while the natural disasters will hit the real economy (including exports) severely in the first half of this year – they are sticking to their plan to push their budget into surplus no matter what – that is, irrespective of whether the economy is slowing down to a crawl having failed to reach trend since the recovery began.

Yesterday’s Retail Trade data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics showed that despite the Christmas period being included, retail sales growth contracted and provided further evidence that the Australian economy is weak.

For the December quarter, retail turnover actually contracted (down 0.3 per cent). That is the first contraction since September 2009. It is clear that households are currently reluctant to expand consumption at any rate and I would suggest that is a wise strategy given the record levels of debt that sector is still carrying. There has to be a significant reduction in those debt levels overall and for that to occur economic growth has to be sustained at a much faster rate than is evident at present.

And with net exports subtracting from growth (despite all the rhetoric about the “mother of all mining booms”) then the Government deficit has to be sustained if not expanded to support on-going income growth. The media never poses that scenario when interviewing the politicians. They have bought the line that the mining sector is driving growth and so the government sector has to withdraw.

My reading of the data and its likely trends suggests a much darker scenario. It is clear that most observers do not understand that even though commodity prices are high and the mining sector is growing the overall impact of net exports on growth (once you take into account the leakage from imports) remains negative. So with private domestic spending still fairly flat (notwithstanding the hope that investment will boom later this year), income support has to come from the public deficit.

And if the natural disasters do reduce the growth rate even further then the deficit has to be that much bigger.

But the productivity report I mentioned at the outset paints an even more worrying – post mining boom – future for this country and has implications for every advanced nation that fails to take care of their most precious resource – the workers.

Australia’s Productivity Challenge Report notes that:

Economists (and others) have long recognized that productivity growth (that is, increases in the level of productivity over time) is the only sustainable source of improvements in a community’s, or a nation’s, material well-being, and that of its citizens in the long run – and that improvements in material well-being can help make possible and sustainable improvements in the non-material aspects of individual, community and national well-being.

In Australia’s case, productivity growth can help us to deal with the challenges of demographic change, to reconcile potential conflicts between environmental constraints on economic growth and widely-held aspirations for further improvements in living standards, and to assist in coping with some of the side-effects of the current ‘resources boom’.

I agree with that statement – noting it talks about “material well-being”. I also agree that increased productivity can help ease the pressures of a rising dependency ratio as a result of an ageing population – which is the real problem of ageing despite the deficit terrorists representing it as a fiscal problem. If we can produce more for less then having less workers available does not mean we have to reduce our standard of living. That should be a major objective of government policy in this regard.

That would indicate strong investment in education and research and development – areas that are being cut in the manic quest for a return to budget surplus. Meanwhile 2 million Australians who could work are being denied the opportunity by the lack of jobs (that is, lack of overall spending) and 25 per cent of our 15-24 year olds – the future productivity of our nation are idle (unemployed or underemployed).

I also agree that some of the issues surrounding environmental sustainability can be attenuated through better technologies. That doesn’t mean that I support the type of claims that the coal industry are making about “clean coal”. Even if that was possible, it would not be a preferred technological advance. More about that topic another day.

But I find the interesting thing about productivity growth is that is the terrain where the conflict between labour and capital plays out despite the claims made by neo-liberal commentators that the old “class” divisions are irrelevant these days. Nothing could be further from the truth. Please read my blog – When will the workers wake up? – for more discussion on this point.

The neo-liberal policy agenda since the 1980s has been firmly focused on reducing government protection of the weak and transferring power to employers by undermining the capacities of trade unions to bargain for advantage. While the public justifications were all about creating more jobs and improving productivity the reality has been different.

Since 1975 there have never been enough jobs available to match the willing labour supply in most nations. It was absurd to tie income support payments to relentless job search when there were not enough jobs. It was inefficient to force the unemployed to engage in on-going training divorced of a paid-work context. But that was lost on these ideologically-obsessed governments and their policy advisers. The fact that we all went along with it is testament to the strength of the misinformation campaign that accompanied the policy onslaught.

The program of deregulation and the attack on workers’ rights was about redistributing real income – that is, getting a greater access for capital to the productivity growth that the economy generated.

However, it is ironic that in one sense this process set in place the conditions for the global financial crisis. But further, and relevant to the Report I am discussing here today – it set into train processes that have eventually undermined the capacity of the economy to drive strong productivity growth. In that regard, the pressure on workers to suppress real wages growth will be even more intense and fiscal austerity will be used to undermine their capacity to defend themselves – by creating entrenched unemployment.

A defining characteristic of the neo-liberal era has been the increasing gap between labour productivity and real wages growth which has resulted in a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital in most countries.

In the past, real wages grew in line with productivity and ensured that firms could realise their expected profits via sales. With real wages lagging well behind productivity growth, a new way had to be found to keep workers consuming. The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector.

Capitalists found that they could sustain sales yet receive an additional bonus in the form of interest payments while also suppressing real wages growth. Households, enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial sector, embarked on a credit binge.

The increasing share of real output (income) expropriated by capital became the gambling chips for the rapidly expanding and de-regulated financial sector. Governments claimed this would create wealth for all. For a while, nominal wealth did grow although its distribution did not become fairer. However, greed got the better of the bankers as they pushed increasingly riskier debt products onto people who were clearly susceptible to default.

This was the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

But the increasing capacity of firms to replace full-time secure jobs with part-time work has also undermined our future productivity prospects. The full-tme jobs were traditionally well-paid and delivered high productivity. Increasingly, the economy has reduced protections (by relaxing unfair dismissal rules; by reducing and eliminating overtime and penalty rate entitlements by abolishing the notion of a standard and non-standard working week etc) and over the last two decades have produced

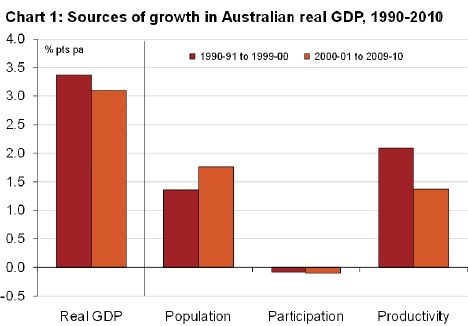

The Report provides a very interesting decomposition of real GDP growth since 1990 and I reproduce their Chart 1 (hate the colours though!) as below. The Report notes that “Australia’s real GDP growth rate averaged 3.4% per annum during the 1990s (that is, from 1990-91 through 1999-2000)” and:

… population growth accounted for 1.4 percentage points per annum (or about two-fifths of the total); and labour productivity growth 2.1 percentage points per annum (or just over three-fifths of the total); while ‘participation’ or labour supply detracted 0.1 of a percentage point per annum (the result of the large rise in unemployment during the recession at the beginning of that decade, which had not been fully unwound by the end of it).

So the refusal of governments to expand deficits sufficiently to generate enough work meant that real GDP growth was constrained during this period not to mention the damage caused to the unemployed.

What about the next decade? For overseas readers, a conservative government was elected in 1996 and set about running budget surpluses and accelerating the neo-liberal policy agenda that the previous Labor government (yes the political arm of the trade union movement) had introduced in the mid-1980s.

The Report notes that:

Over the past decade, Australia’s real GDP growth rate has averaged 3.1% per annum, just ¼ pc point per annum less than during the 1990s. However, the sources of that growth have changed significantly: population growth accounted for 1.8 pc points pa (or just under three-fifths), while labour productivity growth accounted for 1.4 pc points pa (or about 45% of the total). Participation or labour supply growth detracted almost 0.3 of a pc point per annum from real GDP growth, as falling average hours worked more than offset the decline in the unemployment rate and the rise in the labour force participation rate over the course of the decade.

So as the federal government pursued budget surpluses (undermining public infrastructure like education and employment service provision) and dumbed down the labour market through deregulation and pernicious industrial relations legislation the contribution of productivity slumped.

Note also that labour supply growth continued to subtract from growth because underemployment basically replaced unemployment during that period. Both reflect a failure of aggregate demand which was being artificially constrained by the pursuit of budget surpluses.

For the future, we cannot continue to rely on population growth. This is a very arid continent – the recent floods notwithstanding and much of the usable land (for urban settlement) is exhausted. The pro-growth lobby that wants to expand our population via net migration seem to be oblivious to the “holding limitations” of our water and land systems.

The other fascinating thing about the Report is that it highlights that our future as a high income nation is in jeopardy. When I was at school we learned that at the turn of the C20 Australia and Argentina were the wealthiest countries (per capita income) yet Argentina had squandered its fortunes. I cannot recall the slant that was put on that – but I recall it had an anti-Latin component – not working hard enough etc. We were always told that while Australia had slipped somewhat in the world rankings we maintained our wealthy status courtesy of a strong education system and the resulting highly skilled workforce.

Well that seems to be changing which is no surprise to me given the neo-liberal policy onslaught that has progressively starved our public education system of growth funds and dumbed down our higher education system by forcing it to earn its own funds.

Further we have institutionalised persistently high labour underutilisation over the last three decades and introduced policies that increasingly generate low-skill, low pay work in place of high-skill, full-time work.

In many ways, the budget deficit fetishism that the defines the neo-liberal era has systematically starved our productivity building institutions and capacities of funding.

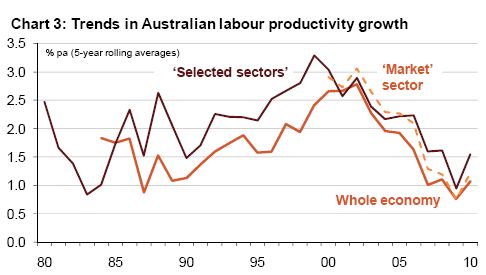

The following graph is Chart 3 in the Productivity Report.

The related commentary says:

Chart 3 shows that, for the economy as a whole, labour productivity growth rose steadily during the 1990s to peak at 2.8% pa over the five years ended 2001-02, well above the long-run average rate of 1.6% pa; but slowed dramatically during the ensuing decade, reaching a low of just 0.8% during the five years ended 2008-09. A similar slowdown is apparent for the ‘market’ sector (as currently defined by ABS); while for the 12 ‘selected sectors’ which formerly comprised the ‘market sector’, labour productivity growth peaked at 3.3% pa over the five years ended 1998-99, before slowing to 0.9% pa over the five years to 2008-09.

It is actually worse than depicted in the graph because when you take into account “capital deepening” (that is, adding extra capital per person employed) the

“the efficiency with which labour and capital were combined (including through the take-up of new technologies) actually went backwards during this period”.

The Report also presents an interesting comparison between Australian and US productivity and reveals that we have fallen backwards in relative terms.

What I found both interesting and disappointing about the Report was its lack of attention to the neo-liberal “reform” process and the impact of that process on productivity performance.

It claims that the major stifling factors contributing to the decline in productivity over the last decade has been legislation surrounding national security (all those characters that frisk you at every airport who add nothing to production).

Then they talk about how “paradoxical ‘downside’ of economic success” where they claim that the sustained growth in the period from 1992 to the recent crisis “lessened the sense of urgency associated with the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s”. We allegedly became victims of a “Great Complacency”.

In this context the Report says that:

But to the extent that Australia’s economic achievements have induced ‘complacency’, it is not confined to policy-makers. As the profit share of Australia’s national income has increased to unprecedented levels during the past decade (apart from the period immediately after the global financial crisis), business has in general attached less urgency to the pursuit of productivity gains at the enterprise or workplace level (which is, after all, where productivity growth actually occurs).

I think this point (which I noted above) undermines their argument about the declining pace of reform in the last decade relative to the previous decade. The redistribution of national income to profits began in earnest in the mid-1980s under the Prices and Incomes Accord which was a cheap stunt to reduce real wages and provide more real income to capital.

That redistribution zeal was further enhanced by the entrenched unemployment that remained throughout the 1990s after the 1991 recession and the subseuqent legislative attacks on trade unions embodied in the 1996 Workplace Relations Act. The wage share collapse accelerated in the latter half of the 1990s just about when the productivity started to decline substantially.

The point is that the “liberalisation” and “reforms” that the Report thinks helped productivity in the 1990s slowly undermined the capacity of the economy to produce productivity growth.

They also claim that economic success damaged our productivity performance in a second way:

The second way in which Australia’s extended period of economic success has detracted from our overall productivity performance is that, as the Australian economy has moved closer to ‘full employment’ of labour and other factors of production (both in the years leading up to the onset of the global financial crisis and, more recently, as the ‘resources boom’ has resumed), it has increasingly encountered ‘capacity constraints’, particularly in the form of shortages of skilled labour and ‘bottlenecks’ in transport and other infrastructure.

I also found this claim to be very misleading. First, we didn’t get close to full employment by the time we reached the peak of the last cycle in February 2008. Total labour underutilisation remained at 9.5 per cent in that quarter. Full employment does not involve wasting that much capacity.

Further our net employment growth in the decade prior to that had been biased to part-time employment with increasing casualisation and underemployment.

There was plenty of excess labour capacity in the Australian economy and the “skill shortage” argument was largely unsustainable.

Moreover, the shortages in transport and other infrastructure are real enough but are direct products of the budget deficit fetishism and thus are tied in with the neo-liberal “reform” process. Ports, previously under public ownership were privatised to make them work better. That was the narrative. But once in private hands, the operators bled the infrastructure for short-term gain and failed to maintain the capacity investment. The classic case is the coal loader infrastructure on the East Coast.

The complacency is thus a direct outcome of entrusting vital infrastructure to private operators who adopt short-term profiteering as a focus.

The reason this Report is important though is that it sends a message to Government about responsible economic management. Starving the economy of skilled workers by entrenching unemployment and cutting funding to education is not a sensible strategy for the long-term prosperity of the nation.

The Report shows that our “material living standards relative to those in other countries” will decline over time if we continue along the path we are now following. The short-term gains from our record “terms of trade (in turn driven almost entirely by events beyond Australia’s direct influence or control, in particular the industrialization and urbanization of China and India)” will evaporate in time.

Then the hard reality of an economy that has been hollowed out by the neo-liberal agenda will be stark. Then the school kids might be learning about Australia’s final demise and we will be in the same boat as Argentina.

The danger is that policy makers will get the wrong end of the stick and see this through their neo-liberal shades. They will thus fail to understand that running budget surpluses at this time is exactly the wrong policy stance and that productivity gains will not come by further deregulation of the labour market.

We need to entrench a high real wage- high productivity culture which has been undermined by the neo-liberals.

A massive investment in public infrastructure and education is the starting point. Making sure everyone who wants a job has one immediately is another urgency.

Conclusion

In the 1990s and beyond our economic growth was propped up by a consumption binge driven by record levels of private debt accumulation. That was not sustainable and now we are seeing households trying to repair their debt-laden balance sheets and slow growth is the result.

More recently, it has been the record terms of trade being driven by China and India that is propping us up. That is also not a sustainable future.

Underlying these ephemeral growth sources is a rotten economic structure starved of skill development and public infrastructure investment as a result of failed policy implementation.

We are now an economy that claims we are satisfied with having 12.5 per cent of our available labour resources doing nothing and 25 per cent of our 15-24 year old doing nothing (neither working or learning).

It is a slippery slide to the bottom and all our leaders can say is that they have to get the budget back in surplus because we are such a robust economy. We have only ourselves to blame for allowing our political parties to trash our legacy.

Anyway, I have a dinner tonight to celebrate the successful PhD result for our guest blogger Victor Quirk who produced a masterful thesis on the political constraints to full employment. I was very lucky to have been his supervisor during his period of study. I learned a lot from his efforts and he will continue to share his ideas on an occasional basis with you.

That is enough for today!

25 per cent of our 15-24 year old doing nothing (neither working or learning).

This is a tragedy. Our corporates have full pockets at the same time bleating about skill shortages. The big corporates have failed to take on enough 15 to 24 year olds to keep their own businesses growing. If they don’t want to operate their own employment pools internally to service their own growth then they should be taxed sufficiently to fund the public sector training the ( un ) employment pool. All this bleating about skills shortages is a re-run of 2006. If in 2006 the big corporations had committed to training pools of future workers they would not be bleating again now. This is a tragedy. Cheers Punchy

That Australian PM woman was on Al Jazeera “Frost over the world” today, still not on view on demand guess they have it a couple of days on the ordinary broadcasting schedule first.

Gillard emphasize how prudent they where and accentuated that every dollar for the natural disasters remedy will be taken away from other public spending.

She also was very happy about the mining boom, so much wealth was flooding in to Australia. Of course it’s nice with an ability to balance trade and don’t be limited in importing. I got the impression she was impressed with the piles of fiat money (wealth). Fiat money created out of thin air abroad (in exchange for depleting your natural capital balance sheet) is so much better than the ones you make self.

She also was concerned about youth unemployment but mentioned that the mining industry in the north west (?) did have difficulty to find employees. Overall she seemed to be satisfied with the state of the economy.

Thanks for that post.

Isn’t it true that the majority of the productivity growth in the 1990’s was due to computer technology developed in the 70’s?

If that’s the case, then there has been very little, if any, productivity growth due to the neo-liberal policies foisted on us since the 80’s.

Congratulations to Victor. I look forward to more guest blogs from him.

You’d’ve thought that high profits would lead to high investment rather than financial engineering to chase good returns?

Skill, capacity and infrastructure shortages? Invest in them.

Instead, ‘entrepreneurs’ are behaving more like rentiers and chase larger shares of slowly if at all growing pies.

Sounds rather like Argentina’s lost century…

my question would be, is productivity growth as necessary as the authors of this report make out. At the limits of the economy the only way to grow is through productivity increases. But with 12% underutilisation, does greater productivity simply mean those with the lions share of disposable income can pay for more while the profits/wage share of output can become more skewed in favour of capital/plutonomists? At the level of the firm, why does productivity growth matter to the worker who is unemployed, it simply means his/her job is being taken over by someone else, or pushing him/her into part time employment. Another question, what value does productivity growth have if it is tied to a production function that assumes full employment of all resources?

Vail Victor!!!

Cheers,

jrbarch

Surely one of the reasons for the dismal productivity performance of recent times is that many of our brightest minds are now in the financial industry, merely circulating wealth rather than creating it.

I can’t help but wonder which country (if there isn’t one already) will be the first to implement a job guarantee, which insures 0% unemployment. Ten minutes after that policy is implemented, that economy will be the fundamentally strongest in the world!

Congratulations to Victor! his guest blogs is absolute first class that spread light in a gloomy economic ideological world nothing less than a masterful thesis could be expected. 🙂

How and why Argentina had a lost century is fascinating. Is wealth inequality the key driver of economic underperformance? It seems to me that a surging economy requires an equal distribution of wealth whilst at the same time the lure of the propect of gross inequality to drive people on. Tragically that is not a very stable scenario.

stone: prosperity is related to flow (income, demand, consumption) that is distributed throughout the system inorder to match supply potential and encourage productive investment. This is clear when money is defined as a medium of exchange and unit of account (price). The problem arises when money is considered to be chiefly a store of value (saving = demand leakage, wealth = stock). Then there is money hoarding that disrupts distributed flow. Unless government makes for for the difference, inventory builds, contraction sets in, unemployment rises and recession sets in. The solution is to discourage saving other than for productive investment and distributed gains from the factors by taxing away economic rent. If government recycles the taxed away economic rent, then this perpetuates current prosperity and expectation of future prosperity, decreasing the overall propensity to save.

The global economy must be considered as a closed system with everyone buying and selling to each other in a distributed fashion that is sustainable, thereby reducing both uncertainty and the need to save inordinately. This reduces the major leakages, saving and net importing, making it simple and predictable for governments to offset leakage in a balanced way. What this requires is replacing emphasis on competition and control with cooperation and coordination, i.e., using intelligence instead of relying an invisible hand that doesn’t exist. It’s a matter of figuring out where to go and how to get there using operational principles instead of failed ideology. However, this necessitates accommodations that a lot of selfish people are not yet willing to make.