It's a big data week for me and today's post is more of a news…

Five years into a pandemic and fiscal fictions have left space for nonsense to propagate

Life expectancy has fallen since Covid in almost every country although the policy response has been exactly the opposite to what should be expected. We now have the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services advocating ‘personal choice’ in vaccine take up while he recommended Vitamin A to deal with a spreading measles outbreak in Texas. Decades of science is being disregarded in favour of ideology. We are now five years into the Covid pandemic and the data suggests that the costs of our disregard will accumulate over time as more people die, become permanently disabled and lose their capacity to work. We also know that the ‘costs’ of the pandemic have been (and will be) borne by the more disadvantaged citizens in the community. I was talking to a medical doctor the other day in a social environment and I learned something new – that in Australia, there is a difficult process that one has to go through to get access to the ‘free’ (on the National Health list) anti-viral drugs if one gets Covid. However, if you have $A1,000 handy, you can ring your GP up and get an instant prescription for the same drugs and avoid all the hassle, which has reduced access significantly for lower income households. Another example of how fiscal fiction (governments haven’t enough money) favour the high income cohorts.

Covid remains a significant cause of death across our countries.

The data – Estimated cumulative excess deaths during COVID-19, World – shows that there are around 27 million people worldwide who are estimated to have died from COVID-19 since the beginning of 2020.

By comparison, a bad influenza season kills about 650,000 per annum (Source)

27 million against around 3.25 million.

Further, it is possible that humanity has now passed ‘peak’ health and that Covid combined with behavioural patterns (increased obesity, etc) have left the human condition in a compromised state.

Certainly, Covid has caused a reduction in life expectancy as well as increasing numbers of people who are more or less permanently infirmed, many of who are now unable to work.

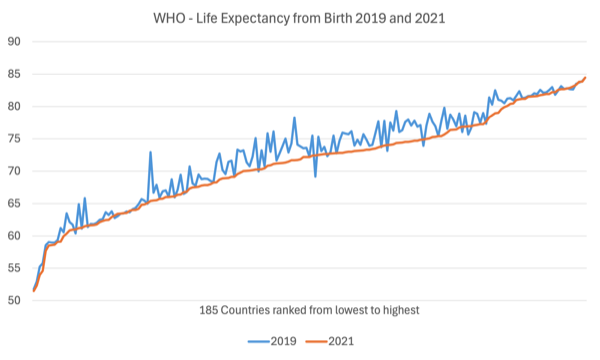

The following graph is taken from WHO data – Life expectancy at birth (years) – and compares 185 countries in the WHO database as at 2019 and 2021, with the data being ranked from lowest (left) to highest (right) as at 2021.

So for almost all countries, life expectancy fell in 2021 compared to 2019 as a result of the Covid pandemic.

The WHO’s Global Health Observatory notes that longer data series demonstrate that:

… lifespans are getting longer up to 2019. However, the COVID-19 pandemic erased nearly a decade’s progress made in improving healthy longevity.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, global life expectancy has increased by more than 6 years between 2000 and 2019 – from 66.8 years in 2000 to 73.1 years in 2019 …

By 2020, both global life expectancy … had rolled back to 2016 levels (72.5 years …). The following year saw further declines, … retreating to 2012 levels (71.4 years …).

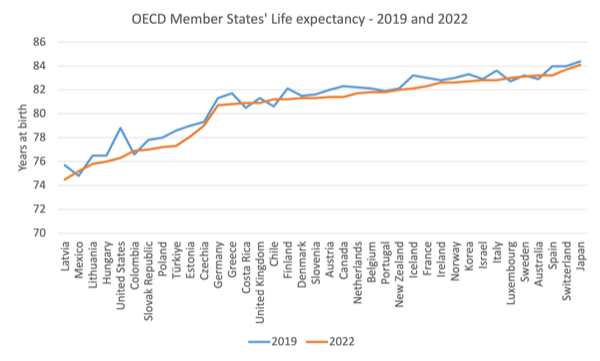

The next graph is from the OECD Member States and adds an additional year (2022) to the comparison.

Again, the same result is apparent – most nations experienced a decline in life expectancy.

In Australia, one of the wealthier nations of the world, ABS – Life expectancy – data (released on November 11, 2024) shows that:

Life expectancy decreased again in 2021-2023, following a decrease in the previous period (2020-2022) which was the first decrease since the mid 1990’s.

Australia ranks fourth for life expectancy in 2022, behind Japan (1st), Switzerland (2nd), and South Korea (3rd).

I had my 8th Covid booster last week and the vaccine provider told me that she was now only administering around 1 dose per week whereas some years ago there was a booking sheet and waiting list full.

I was very young when the polio vaccine was first released and it ended the crisis at the time.

I support the science in this regard.

The provider also asked me when I entered the clinic: “We cannot give the vaccine if you are sick today?”

I responded: “No, I am not sick but why did you ask that?”

She said: “Well you are wearing a clinical mask.”

I said to her that I wear a P95 mask whenever I go into a building or catch a plane, train or taxi.

She was surprised.

I thought that was also indicative of where we are at.

Finger crossed – I still have not have Covid and I fly every week and I also don’t get colds etc anymore.

And, as a bonus, my hay fever is much reduced since Covid.

Masks!

Various governments around the world are backing CEO’s of major organisations and corporations in ordering their workforces to abandon the flexible work arrangements, which has given workers more freedom and protected their health somewhat.

In August 2024, 56.9 per cent of Australian employees told the ABS in their – Working arrangements – survey (latest data released December 9, 2024) – that they “usually worked from home” (that is, 5,168 thousand).

In August 2019, the percentage was 47.3 per cent.

The reasons varied but the majority of respondents cited increased flexibility, fewer distractions, less time spent commuting among others.

In terms of avoiding respiratory illnesses transmitted through air, it is safer working from home if you can.

I know that for many lower-income workers that is not possible but that does not mean that those workers that have the option should not be able to take it.

It just means that health and safety regulations should ensure proper ventilation in workplaces and encourage mask wearing.

Despite these health advantages, it seems that many CEOs hate this because they want more face-to-face control – the perennial capitalist problem.

The Australian Opposition is tripping over itself to out-Trump Trump and claim if they win the upcoming federal election then all public servants will be forced to abandon working from home.

That is, the smaller number that survive their announced cuts to the workforce.

Out-Trumping Trump.

The UK Guardian ran a few articles recently that reflected on where we are at after 5 years of the pandemic.

They give pause for thought.

The recent UK Guardian article (March 5, 2025) – Five years on: Britons among hardest hit by Covid fallout – provides some insights into the folly of ignoring pandemics and the dangerous trends that have followed as the ‘Right’ take control of the narrative across the world.

The article documents several trends including the fact that research funding to study infectious diseases is “drying up” which will reduce the capacity of medical scientists to “predict and prevent the next pandemic”.

In the US, “The Trump administration has sown disarray at its medical research agency, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and ordered US withdrawal from the only global public health agency, the World Health Organization.”

This attack on medical research funding is, as an aside, coincident with attacks on social science research into matters Middle East.

It is now becoming quite risky to be researching or commenting on anything to do with Palestine and related matters.

The scourge of the Right has spread its tentacles wide.

An interesting conclusion from the article is captured by the quote:

In a real crisis, the state can’t look after you … It can’t put food on your table, or walk your dog. We do it for each other.

I am working on research about food security at present and the way communities can localise food production and distribution.

I live in an experimental community that has a massive community farm that produces incredible amounts of food.

It is a model for how our future communities might organise.

It has implications for how we deal with pandemics and climate change as well.

More about that another day.

But where the ‘state’ is crucial is in its fiscal capacity – see below.

A related article (cited in the Guardian article) – Richard Hatchett reflects on a “banner year for viruses” and looks ahead to 2025 (published by CEPI on December 20, 2024) – predicts that more pandemics are coming.

The author is CEO of CEPI, which is the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and is funded by various governments and philanthropic organisations

A number of infectious disease outbreaks are listed for Africa, South America, and North America, which leads the author to conclude that:

These outbreaks, individually and collectively, were notable for their scale and geographic reach and for their diverse epidemiology and virology. One wouldn’t be wrong to conclude that where viruses are concerned the world is on fire.

The article notes that our preparedness for pandemics is being undermined by “the polarization of our societies and pathologies of our geopolitics”.

One problem is the “loss of public confidence”.

A related problem in all this commentary is that the authors argue that governments are “grappling with serious fiscal constraints … that demand attention”.

So while their understanding of the issues relating to ignoring science are sound (in my view) they undermine their own advocacy by conceding to the fictions relating to the capacity of governments to adequately fund sensible health policies both the scientific and social elements.

Once we understand the currency capacities of governments then we can much better protect low-income workers by ensuring they get sufficient sick pay to stay at home and not spread disease.

There is no financial constraint preventing governments from achieving that outcome.

And they could use their legislative capacity to ensure no worker shielded in this way is subject to dismissal or other coercive pressure from their employer.

That would significantly reduce the inequality that arose during Covid as low-income workers were forced by economic circumstance to continue face-to-face work while sick.

Another UK Guardian article (March 9, 2025) – ‘The pandemic reinforced existing inequalities – it was a magnifying glass’: how Covid changed Britain – considers the distributional aspects of the Covid outbreak and the resulting policy response.

It also makes fundamental errors when it comes to discussing fiscal matters:

One of the certainties is that the UK government borrowed a vast amount of money during the pandemic, a debt of about £339bn …

That means paying extra interest of about £16bn, roughly half the annual defence budget – a huge problem for Rachel Reeves, the chancellor.

That theme is often undermining sensible health policy discussions.

Clearly, I favour no debt being issued at all, given it is unnecessary for government spending (where the national government issues its own currency).

And even if the government issues debt, it can use its central bank to control ‘interest payments’ at any level it chooses.

Will bond markets still purchase debt at low yields?

Well they queued up to buy 10-year Japanese government bonds at negative yields, for example.

Further, is the extra interest the UK government is paying out now a problem?

It is income to the non-government sector.

Inflation is falling and unemployment is certainly higher than necessary.

So there does not appear to be a lack of real resources that can be brought back into productive use via extra government spending.

The relevance to the health debate is that running down national health capacity to save money is a myopic strategy as many nations learned during the pandemic.

Not funding aged care facilities is myopic for the same reasons.

The pandemic stretched trained staff capacity and health departments found they were short of essential protective equipment.

The front line between chaos and disaster when a pandemic hits are the cleaners, the nurses, the paramedics etc.

Not funding an adequate supply of such staff and underpaying them is likely to be disastrous as we learned.

A cleaner should be paid more than university professors but they are at the bottom of the wage distribution.

The other issue that the pandemic exposed was the quality of housing, particularly for low-income families.

When forced to work from home, or stay at home, living spaces soon were ‘over occupied’.

The trend by greedy property developers to build small ‘shoe box’ apartments to maximise their project return exacerbated that problem.

Higher income families fared better, which means that there is an increased need for adequate state housing to be built and supplied that allows low income families to live reasonably when confined to home during the next pandemic.

Once again the lack of adequate supplies of such housing (in Australia it is estimated that the social housing gap is currently around 800,000) is testament to the myopia triggered by the fiscal fictions that the government cannot afford to fund such developments.

Conclusion

The health issue is just one dimension of the poly crisis that neoliberalism has engendered.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The “rules based world order” has diferent rules, as for what is considered illegal.

If Invading Ukraine is illegal (and rightly so), ethnical cleansing of a country in the middle east is perfectly legal to the same ones.

What is the common denominator between the two?

Racist prejudice!

Yes, my friends, never racism was so rampant as now.

The global south needs to jump from the chair.

Science cannot make value judgements. Science can help us understand how things work. But science cannot tell us how to balance competing values.

Mennonites in Texas (and elsewhere) should not be forced to undergo involuntary vaccination.

The G’s Five Years On (from Covid) is worthy of reading (except of course we are only 5 years on from the start in Europe/UK and not from the beginning of the end, due to the Govt’s mishandling). Would that Starmer and his cronies would realise that putting resources into helping invalid people would bring them closer to being able to work than hounding them and cutting sickness benefit.

‘A cleaner should be paid more than university professors but they are at the bottom of the wage distribution.’ It’s such a fundamental injustice from our class system + capitalism that the most wretched jobs, and often the most necessary, that most people would avoid even if the pay was greater, are paid the least, while those that people would choose to do for their lifestyle or interest or greed are much more greatly renumerated. The most explicit example of the state acting to keep it this way, was the force swung against the coal miners in the 70s and 80s, firstly striking for decent wages and then for a job.

Life expectancy in Australia is also related to availablity of housing.

And overcoming the Oz housing crisis ASAP requires the public sector to displace the private sector *until sufficient housing has been built to house everyone*.

In other words, the private sector market has ceased to function as required to house everyone, aka ‘market failure’.

But just a year ago, Stephanie Kelton (in her last visit to Oz) insisted “MMT doesn’t mean increasing the size of government”, in answer to a comment from the ABC’s Natasha Mitchell who observed that increasing the size of government (Mitchell’s correct observation of the *possibilities* of what Kelton is arguing) is not accepted by politicians and the media who are captured by mainstream economists and their free-market religion.

Duh.

Obviously the Oz government MUST *sub-contract* the nation’s entire building industry for as long as necessary (as noted above) , funded by Treasury *without taxing or borrowing from the private sector.*

That is, without taxing (….taxes – and hence borrowing – being politically toxic) in order to create the fiscal space required by the public sector to maximize the nation’s capacity to deliver housing ASAP.

Inflation will not be an issue because the government will have merely ‘commanded’ the nation’s *alreadyu available* building-industry resources (for as long as required) , hence avoiding excess demand caused by competition between the public and private serctor.

……..

Notice the chaos to to which the global ‘competitive free market’ religion has brought us, as the world’s most powerful man wants to ‘MAGA’ (in part to “save the ‘free’ world”…..) , which he believes can only happen through pauperizing the rest of the world; he is understandably outraged by the decades long deindustrialization in the US, under the global ‘competitve free trade’/’small government’ religion which even many MMTers seem to worship…..

But unfortunately Trump is controlled by puppet-master Musk – a creative genius, but a macro- economic ignoramus….

Heard a comment on radio today that timber required by the buliding industry in Oz is in short supply because “the economics” (sic) result in plantation timber being exported to overseas markets as chips, rather than ‘value-added’ here to create building-grade timber for local use, because no-one, not the private-sector money-bags, nor the “broke” government, wants to outlay the necessary *investment* in value-adding.

Deplorable.

( At least Albo IS committed to saving Whyalla…..)

@Neil Halliday Media coverage (in the UK) of Cyclone Alfred elicited one of those rare succinct from the people comments. When asked why she was homeless, the woman replied, ‘because there’s a housing crisis mate’.

In the UK the government makes out that it cares, not so much for the homeless, but for ‘hard working’ people struggling or not able to be homeowners. But while the wealthy middle class invest in 2nd homes and acres of precious undertaxed land is taken up by their surplus bedroom mansions, just as in Australia, it places its hopes on the housing industry not only to finance and build lots of new homes, but to make a few of them ‘affordable’. It then pressures cash-strapped local councils to do the deals with housebuilders, and one can guarantee that affordable will go out of the window.

Neoliberal atomization makes public health impossible.