It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Job vacancies rising in Britain in mostly below-average pay sectors

Part of my working day is spent updating databases and studying the additional observations. I learn a lot that way about trends and how far off the mark my expectations of a particular phenomenon might be. Today I updated various labour market datasets from Britain and did some digging into the relationship between vacancies and pay. It is clear that as the British economy opens up again, that unfilled job vacancies have grown very strongly over the Northern summer. While that is a good thing because it means there are opportunities for workers to gain employment, shift employment to better paying jobs etc, the message is no unambiguous. If the vacancy growth is biased towards low-pay work then the chances for upward mobility might be stifled. Such a trend might also reflect the fact that employers are now finding that their old practices of accessing vast pools of EU labour willing to work at low wages are being constrained and that will signal the need for a change in strategy, including restructuring, capital investment and better paid jobs. It is too early to discern which way that will go. But what I found while looking at this new data is that while job vacancies are booming, the majority of them are in below-average pay sectors. More analysis is needed to fully assess the implications. Here is where I started on this path …

Two major British datasets were updated last week by the Office of National Statistics:

1. Vacancies and jobs in the UK: September 2021 (released September 14, 2021).

2. Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: September 2021 (released September 14, 2021).

Individually, they are of interest but when some of the information is merged some additional insights emerge.

There was a report put out by the British Institute of Fiscal Studies –

Job opportunities during the pandemic (September 21, 2021) – which followed the release by the ONS of the latest vacancy and employment data.

The IFS were seeking to investigate the issue of bottlenecks in the labour market among other things, given that some vocal employers have been claiming they cannot access skilled workers.

When I investigated that claim some months ago I concluded that the reduced access to workers who would work for low pay and poor conditions as a result of Covid and Brexit coincided with the fact that the employers seemed unwilling to pay market rates for the labour that was available.

The IFS use more detailed vacancy data than that published by the ONS. It is based on on-line job adverts matched to official data in the Labour Force Survey.

They found that the:

The recent recovery in vacancies has been strongest in traditionally lower-paid occupations. This largely, though not entirely, reflects the surge in road transport driving and storage vacancies. In fact, as of June 2021, vacancies in the lowest-paying third of occupations (when ranked according to pre-pandemic wage levels) are now 19% higher than pre-pandemic, while vacancies in other occupations have only just returned to pre-pandemic levels.

I thought that was a proposition that was worth exploring further because on first blush it is difficult to draw that conclusion from the official data.

So I went digging.

There is no doubt that vacancies overall are growing very quickly.

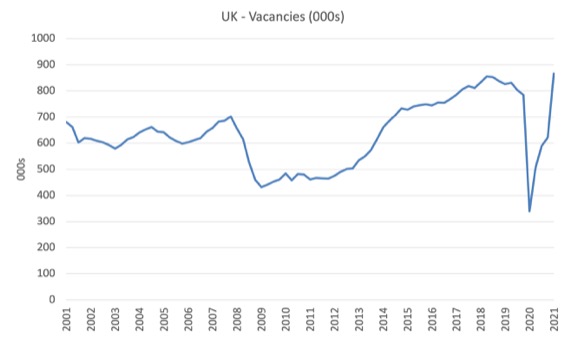

The following graph shows the evolution of job vacancies over the last two decades to the June-quarter 2021.

The vacancies per 100 employees was 1.1 in the June-quarter 2020. By June-quarter 2021, the rate had risen to 2.9 rising 0.8 points in the quarter.

That is quite a strong movement in historical terms.

How we assess that situation depends on a range of factors, not the least where the vacancies are arising.

The implication of the IFS research is that the major proportion of vacancies is arising because employers cannot find low-paid workers.

Is there truth in that conclusion?

The first thing to do is investigate what has happened to employment since the pandemic.

Employment changes since pandemic by industry

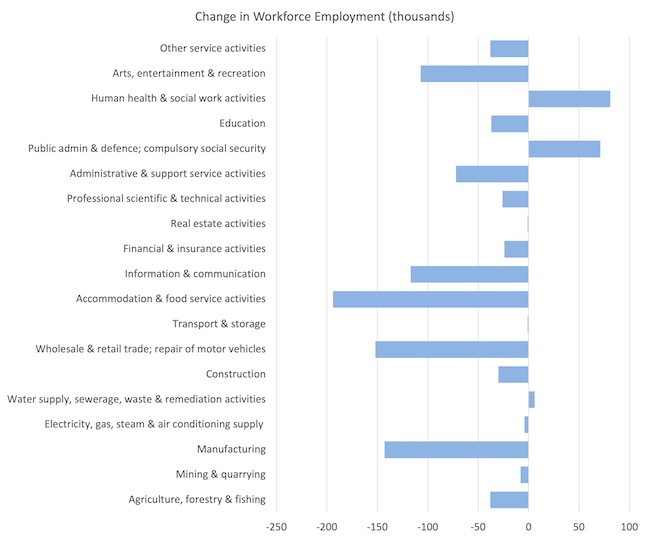

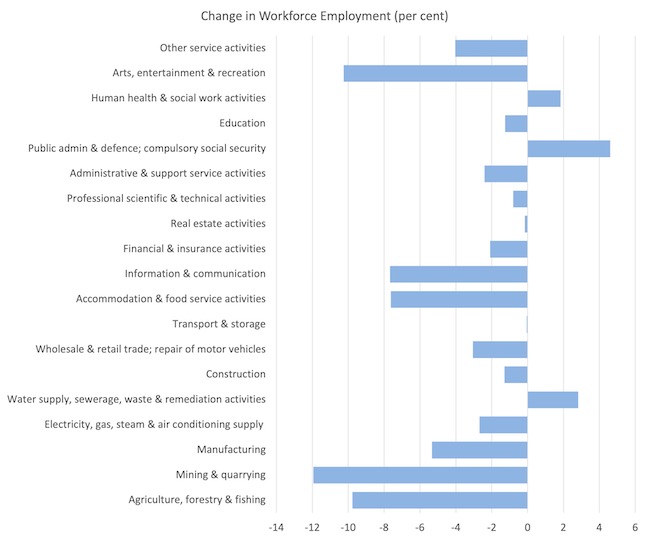

In terms of where total workforce employment (employees plus self-employed) is at the June-quarter 2021 relative to the beginning of the pandemic (March-quarter 2020), the following facts emerge:

1. Total employment is still 831 thousand or 2.3 per cent the March-quarter, pre-pandemic peak.

2. Total employment for employees is 541 thousand or 1.8 per cent below the pre-pandemic peak.

3. Total self employment is 294 thousand or 6.5 per cent below the pre-pandemic peak.

4. Total employment growth was already started to slow from the June-quarter 2016, well before the pandemic.

5. There is considerable diversity across the industry sectors as the following graphs show.

The first two show the change in Total workforce employment from the March-quarter 2020 to the June-quarter 2021 by sector in thousands (first graph) and percentage terms (second graph).

You can see that only three sectors have higher employment levels – Human health and social work activities, Public Administration etc, and the Utilities.

Total Workforce (thousands and per cent, respectively)

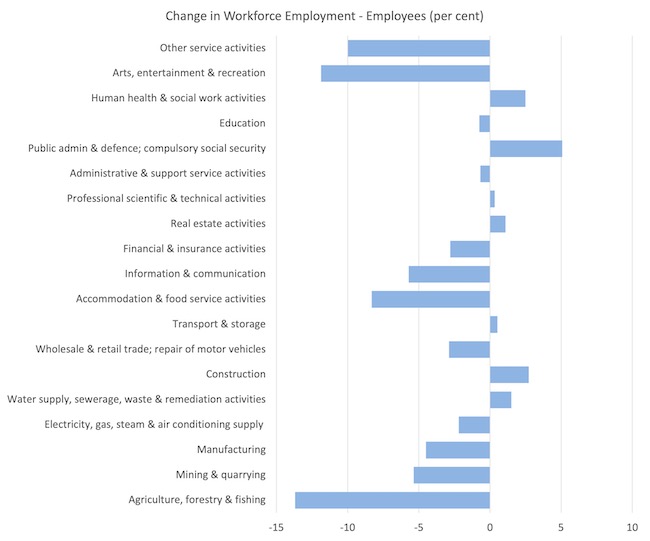

Employees (thousands and per cent, respectively)

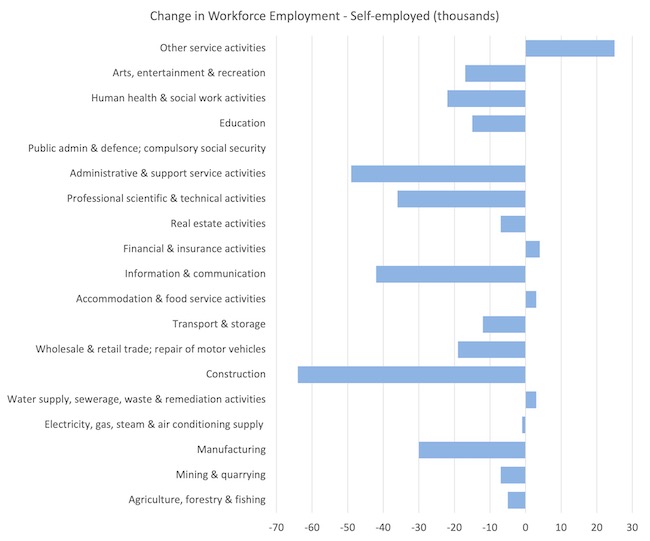

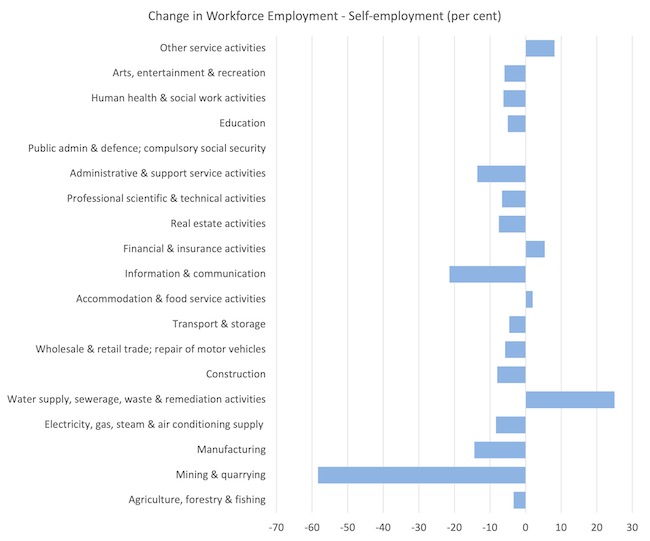

Self-employed ( (thousands and per cent, respectively)

We see that in several sectors, the self-employed workers have gone backwards relative to those in the same sector that have employee status.

Vacancies and Earnings

Job vacancies are now 231 thousand (29 per cent) higher than the level observed in the December-quarter 2019.

The following table summarises the relevant data.

Ignoring the Utilities, The strongest growth in vacancies has been in:

1. Arts, Entertainment and Recreation (76 per cent; 5.6 per cent of the total change).

2. Accommodation and Food Service Activities (52 per cent; 19.9 per cent of the total change).

3. Transport and Storage (47 per cent; 6.5 per cent of the total change).

4. Construction (42 per cent; 4.8 per cent of the total change).

5. Information and Communication (41 per cent; 7.4 per cent of the total change).

The overall median weekly wage in 2020 was £479.10 while the average was £572.70.

One convention employed by advanced nations is to define a poverty line at 60 per cent of the nation’s median wage (income).

The UKs National Living Wage (NLW), which was introduced in 2016 considered the 60 per cent threshold to be the aspiration to reduce the incidence of low pay.

In 2020, that level was £287.46 per week.

Accordingly, the low-wage sectors in the UK are Retail (median weekly earnings of £285) and Accommodation and food services (median weekly earnings of £208.60).

We should be careful here though given that we are using sectoral rather than occupational data.

Even within an industry sector there is a wide disparity between the high- and low-paying occupations.

For example, in Transportation and Storage which has a median weekly earnings (2020) of £568.4, well over the 60 per cent threshold, the following sub-sectors record median weekly earnings as follows:

Land transport and transport via pipelines – £565.00

Water transport – £582.60

Air transport – n/a

Warehousing and support activities for transportation – £586.60

Postal and courier activities – £481.60

And within those sub-sectors, there is also disparity.

So while nearly 20 per cent of the change in vacancies between the end of 2019 and August 2021 were in Accommodation and food services, which is clearly a low-wage sector, the smaller proportion of vacancies change, say in Transport and Storage, which is not a low-wage sector overall, might have been at the bottom of the pay distribution.

Assessment:

1. 46.9 per cent of the change in vacancies since the end of 2019 were in above-average weekly median pay sectors.

2. 19 per cent of the change were in low-pay sectors.

3. The majority of the change in vacancies are in below-average pay sectors.

Conclusion

I am currently investigating occupational data to see if I can understand what is going on a bit more fully.

But what I suspect will happen is that British firms that have been paying relatively low pay to workers will be forced by the shortages of labour to restructure their workplaces and pay more or go out of business.

That is a good thing.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

So many pressures on businesses and labor involved.

In Canada, many of the lower paid jobs were considered essential, so those workers faced increased health risks and far worse working conditions during lock down. Many became infected with covid due to unsafe working conditions, and some of those people are coping with long covid now.

Even in the higher paid health care sector, workers are finding conditions unbearable and leaving their jobs, seniority, behind.

Those employed in non essential services were out of work altogether. Although most received income assistance from the government, many workers have had time to reevaluate their vulnerabilities and the precariousness of their occupation, and are opting to search for something more secure given the new work environment.

As the cycle of reopening and closing in sync with the pandemic waves continues, business struggles to find ways to survive in an uncertain environment were profit potential is greatly reduced, due to increased public health regulatory requirements; this situation may exist well into the future, despite vaccine availability.

There is a tendency to ask workers to do more for less , at a time were they estimate the increased difficulty of their job annd what they have been enduring should be worth more. Prices for food, shelter and energy are increasing.

“While that is a good thing because it means there are opportunities for workers to gain employment, shift employment to better paying jobs etc, the message is [extra word removed] unambiguous.”

I wish, but per my parasocial relationships, the message is that the fault is pretty much Brexit. Wouldn’t surprise me if Tories and Labour take advantage of it, either. It also seems to be taking a toll on anti-european sentiment within the EU.

It was impossible to travel a distance of 5 Kim’s in London today without running into gridlock traffic as people queued outside petrol stations.. the shortages (whether perceived or actual) are leading to hoarding and discontent.

Add to this the fact that gas pricing are climbing and energy bills are set to increase 40%.

Rather than wage increases, what we’re likely to see is a Tory government that goes back on election promises and once again allows immigration of cheap labour from Eastern Europe in order to satisfy corporate agendas. Add to this the utterly regressive increase in the “national insurance” tax (which everyone assumes funds the NHS), and the end of the universal credit increase, and households in the UK are probably going to go through a tough winter.

It’s a shame that rather than seize this opportunity, on one hand Sunak keeps bumbling on about sound finances and reducing the deficit, and on the other BoJo encourages further decent into cronyism.

“Postal and courier activities – £481.60” median?

Is this real? I work as that currently and it’s more like nearer to the NLW threshold.