I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

A response to Greg Mankiw – Part 3

Before Xmas, I published a two-part reply to Gregory Mankiw’s paper on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – A Skeptic’s Guide to Modern Monetary Theory (December 12, 2019). I was trying to get the response finished before the break and Part 2 had already become too long. So I decided to leave one issue that I didn’t get to address for a shorter third response once service resumed. I think this part of the response is necessary to set right on the public record. It exemplifies how critics need to work harder to actually understand what MMT is about. And while they try to claim that MMT is opaque and difficult to get to terms with, thereby sheeting the blame for their misguided renditions of our work back onto us, the issue I discuss today is very easy to come to terms with. It is front and centre and there have been many scholarly and other articles written about it. I refer, of course, to the Job Guarantee as MMTs response to the mainstream Phillips curve. The failure to appreciate where this sits in the MMT framework is not confined to mainstream economists. But this group know all about the Phillips curve literature and the place it holds in their macroeconomics. So there is no excuse not to understand it within a buffer stock framework and how MMT responds.

Previous posts:

1. A response to Greg Mankiw – Part 1 (December 23, 2019).

2. A response to Greg Mankiw – Part 2 (December 24, 2019).

Since Part 2 was published last week, there has been further correspondence with Greg (on his initial instigation), which clarified some of the unknowns laid out in Part 1.

He assured us that he was acting in good faith (which I accept) and had “spent several months reading … [our] … book carefully”. He also said his initial intention when he wrote to us initially was different to what eventually was produced in the “Skeptic’s Guide”.

The shift was driven by deadlines.

While I have no reason to doubt any of that, I still think it is beholden on an academic critic to render the object of criticism fairly.

I don’t think his “Skeptic’s Guide” is a fair rendition for reasons I outlined in Part 2 and will extend in this part today.

In fact, his readers will come away from reading his paper with a very weird version of our work. I hope they are curious and come back to source to learn how they have been mislead – intentionally or otherwise.

So here is one way his readers were totally mislead about MMT.

Somehow Greg Mankiw missed a major departure of MMT from the mainstream he loves

In his critical ‘guide’ (or non-guide as it happens), Greg Mankiw writes:

MMT proponents advance a very different approach to inflation. They write, “Conflict theory situates the problem of inflation as being intrinsic to the power relations between workers and capital (class conflict), which are mediated by government within a capitalist system.” (MW&W, p. 255) That is, inflation gets out of control when workers and capitalists each struggle to claim a larger share of national income. According to this view, incomes policies, such as government guidelines for wages and prices, are a solution to high inflation. MMT advocates see these guidelines, and even government controls on wages and prices, as a kind of arbitration in the ongoing class struggle. (MW&W, pp. 264-265)

This is a totally inaccurate account of the MMT approach to inflation control and reflects badly on his claim to have read our – Macroeconomics – textbook faithfully before writing about it.

In Chapter 17 on ‘Unemployment and Inflation’, we do consider incomes policies (Section 17.5) in the context of inflation being the outcome of the distributional struggle over real income shares by labour and capital, fought out by each claimant pushing nominal wages and/or prices up.

We say that:

Governments facing a wage price spiral and who are reluctant to introduce a sharp contraction in the economy, which might otherwise discipline the combatants in the distributional struggle, have from time to time considered the use of so called incomes policies.

Progressive economists often advocate the use of incomes policies to rein in cost pressures to avoid the need to reduce overall spending, which creates higher involuntary unemployment.

We document historical episodes in various countries of attempts to use incomes policies to control inflation.

We conclude that, in general, that historical trends (institutions etc) have made the “operation of incomes policies difficult” despite this approach have been successful in some nations (for example, Scandinavian economies).

Nowhere in that discussion do we say that the MMT approach to inflation is to use incomes policy.

In fact, we closed the discussion with this:

In Chapter 19, we will introduce the concept of employment and unemployment buffer stocks in a macroeconomy and analyse how they can be manipulated by policy to maintain price stability.

And in Chapter 19, at the outset, we reflect on the material in Chapter 17 before pursuing the “main focus” which is to analyse:

… two approaches to achieve sustained low and stable inflation (inflation proofing). We construct the discussion in terms of a comparison between two types of buffer stocks, both of which are created by government policy aimed at avoiding aggregate demand pressures that might fuel an inflationary spiral.

And:

The two buffer stocks that we will compare are:

- Unemployment Buffer Stocks: Under a Natural Rate of Unemployment (NRU) also referred to a Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) regime, inflation is controlled using tight monetary and fiscal policy, which leads to a buffer stock of unemployment. This is a very costly and unreliable target for policy makers who are trying to achieve price stability.

- Employment Buffer Stocks: The national government exploits the fiscal power embodied in a fiat currency issuing system to introduce full employment based on an employment buffer stock. The Job Guarantee (JG) model is an example of this type of policy approach.

Both buffer stock approaches to inflation control introduce so called inflation anchors. In the NAIRU case, the anchor is unemployment, which serves to discipline the labour market and prevent inflationary wage demands from being pursued. Under a Job Guarantee, the inflation anchor is provided in the form of an unconditional, fixed wage employment guarantee provided by the government.

And, in stating our objective for the rest of the Chapter we conclude that:

Finally we outline and contrast the two buffer stock schemes, which are designed to control inflation. We show that only a Job Guarantee approach provides an employed buffer stock that promotes both full employment and price stability.

That could not have been stated more clearly than that.

A central organising concept in New Keynesian (Mankiw) macroeconomics is the NAIRU.

A central organising concept in MMT is the Job Guarantee.

The latter is a specifically designed departure from the former.

Later on, as we introduce each ‘buffer stock’ framework specifically, we note:

As we demonstrate, a Job Guarantee (JG) is at the centrepiece of MMT reasoning. It is neither an emergency policy nor a substitute for private employment, but rather would become a permanent complement to private sector employment. A direct job creation program can provide employment at a basic wage for those who cannot otherwise find work. No other program can guarantee access to jobs at decent wages. Further, the JG approach has the advantage that it simultaneously deals with the main objection to full employment: the Phillips curve argument that the maintenance of full employment causes unsustainable rates of inflation.

In Section 19.6, we show the way the introduction of a Job Guarantee, which we had earlier analysed in detail, replaces the traditional Phillips curve.

Given the centrality of the Phillips curve, the relationship between inflation and unemployment, in the mainstream macroeconomics framework and the embedded concept of the NAIRU in that framework, one would have thought that a section on this topic where the assertion was that employed buffer stocks replace the NAIRU would have piqued the interest of a New Keyesian seeking to understand our work.

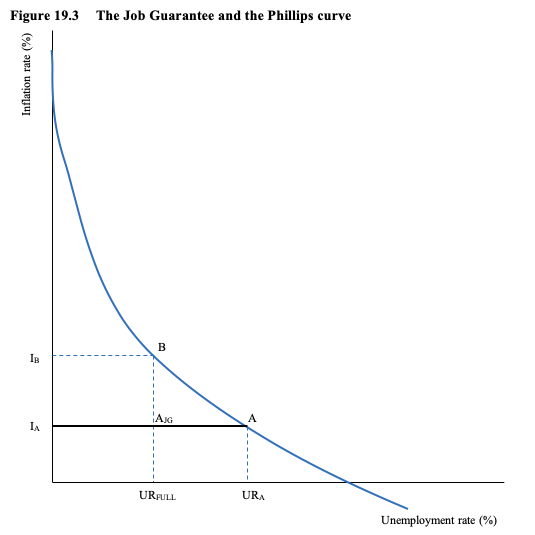

Figure 19.3 in the textbook explained how “the introduction of the JG eliminates the Phillips curve”. Which is quite a statement and hardly one that a mainstream reviewer intent on producing a ‘skeptics guide’ would allow to pass without comment.

The diagram (produced below) contrasts the dynamics of a Phillips curve world, where lower unemployment is associated with higher inflation rates to an economy where an employment buffer stock is used.

The text says that we might start with a Phillips curve world where the unemployment rate is currently at URA, the inflation rate was IA, and the full employment unemployment rate is URFULL, which denotes frictional unemployment.

We posit that the government wants to reduce unemployment and knows that if it increases aggregate spending it will set off cost pressures that drive the inflation rate up to IB – which in the Phillips curve world takes us from Point A to Point B.

We get full employment but a higher inflation rate.

In the NAIRU model, inflation would not be stable at B because bargaining agents (workers and firms) would incorporate the new higher inflation rate into their expectations and the Phillips curve would start moving out.

We considered that issue in detail in Chapter 18 of the textbook where we provided a faithful rendering of the mainstream theoretical approach.

Now consider what would happen in Figure 19.3 if the government introduced a Job Guarantee when the economy was at A.

The Job Guarantee could absorb workers in jobs commensurate with the difference between URA and URFULL, although in reality, as more work was available, workers from outside the labour force (the hidden unemployed) would also take Job Guarantee jobs in preference to remaining without income.

But whatever the quantum of workers that would initially be absorbed in the Job Guarantee pool, the economy would move from A to AJG rather than from A to B.

So we find that when there is a Job Guarantee operating, full employment and price stability go hand in hand.

This is why MMT considers the Job Guarantee replaces the Phillips Curve as a major conceptual device and policy application.

This is no small issue.

Conclusion

I hope that Greg Mankiw changes his “Skeptic’s guide” when he presents it in the coming days at a major conference in the US.

He has clearly misrepresented our work in significant ways and that should not be tolerated in an academic milieu.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Yes, it was notable that Greg Mankiw did not mention the Job Guarantee in his ‘guide’ to MMT. And that bothered me. And that got way worse once he ‘explained’ how MMT would deal with inflation. But it is also something I can understand to a certain extent. Because I occasionally have had problems here myself.

It goes like this. Since there are no countries that currently actually have a MMT Job Guarantee, then this part of MMT does not fall into what we might call ‘descriptions’ of the economic system. And therefore it falls into a ‘prescriptive’ category of MMT policy recommendations. And given political realities, the chances that a JG will happen in the next few years in my country are very close to zero despite my wishes. In my opinion of course. But probably in Greg Mankiw’s opinion also.

So while I can’t believe he didn’t at least mention the JG if he was trying to explain MMT to people, I don’t know that it is some kind of ‘academic malfeasance’ that he didn’t. His almost straightaway jump to ‘MMT recommends government price controls’ as the solution for inflation is pretty bad though, and it wouldn’t be the first thing I would say MMT recommends in the absence of a Job Guarantee.

And the guy actually read your book before writing his ‘guide’ to MMT. Which obviously should be expected. But seems so rare in the case of MMT critiques that it seems worthy of applause, if only in comparison.

Bill,

I’m just an intelligent person when it comes to economics.

Can I say that that diagram makes no sense to me.

What does the bold line from I-subA to I-subJG and straight on to A mean?

Where has the “Economy” moved to?

If it went to I-subJG then you provided zero evidence to show why that would happen.

Is it not true that “the economy” must always be at a point on this graph. That the economy can’t be on a line with many values of UR and/or IR at a given time. It must be a point, right?

It seems to me that it would have gone to the point you called I-subA. That is where Inflation is at “I” and the UR is at “zero” because everyone has a job then.

Why the IR would be the same is strange. I would expect there to have been some increase in prices and then for Inflation to stabilize. I would expect to see the bold line A to I-subA to be curved up then down to the end point at zero UR and IR-subB slightly above IR-subA. [Are these points called I-subA or IR-subA?]

But, I’m not an expert.

Even so, a few reasons why the line does what you say it does would help convince people.

“the chances that a JG will happen in the next few years in my country are very close to zero”

Jerry:

I assume this is because of politics. How about a different approach to getting there? Instead of trying to implement a top-down managed program, how about implementing a program offering a bottom-up managed approach? For example, set up a Federal website on which local governments can set up a page offering local work that will be paid for by the government. An unemployed can access the site to see what local work is available (eg, cleaning up a local park, holding street signs during maintenance, in-home hospice care, housing renovation, etc.) with a direct digital comm channel to the local-government person who will be managing the work so they can talk with each other to (judge mutual interest). Couple this with an automated Fed-pay system that provides fast payment for the work, like by next day. (Worker gets Fed account with debit card first time worked; local manager auto posts hours worked at day end.) Then let local governments join in to take advantage of the free help as they wish.

This could be easily automated as a program without raising eyebrows (even if that required limiting initial eligibility to some congressional district as a test). Feds role would be simply setting the rules (with on-going policing) and auto-paying the bills. (I’m using Fed here as Federal government, not Federal Reserve.) With a well-designed system, I suspect local governments would participate without requiring additional personnel to coordinate. This could start the counter-cyclical stabilization that MMT is looking for yet grow into a full-fledged Jobs program.

I fund it noteworthy that Mankiw has not offered a comment here. Is he not listening to a pretty blistering critique? Has he deigned it not worthy of his attention to continue with what ought to be a discussion that would enlighten us all? Is he just rude? Is he so cowardly that he won’t bother to defend himself and his paradigm? Is he afraid that he’ll lose this particular battle/war? Is he so self-confident that he’s “winning” that he doesn’t even think he needs to pay attention? Has anyone forwarded this critique to him so he can consider it in more detail? Lots of questions, hmmm?

@Steve_American; my observations:

The horizontal line IsubA to A represents the (fixed) inflation rate, associated with the introduction of a JG. So as the inflation and associated unemployment in the economy *shown by the point A* moves leftward, ie, as unemployment is reduced when the JG is introduced, inflation stays the same (as opposed to the Philips curve where inflation increases) .

The assumption is there are sufficient (unused) available resources in the economy (at A) to allow extra consumption to occur without price increases, as employment increases.

I see the horizontal line as a statement that there are sufficient resources in most economies to house, clothe, feed, transport, connect to the internet, AND employ everyone, in most economies.

Obviously this does not mean everyone will be able to afford luxury overseas travel, or luxury vehicles (indeed extra public housing and transport will be required), because inter alia, some nations will be more productive than others.

Whether the horizontal line is always exactly horizonal is probably not significant, so long as it is roughly horizontal as JG employment increases.

Edward Zimmer, thanks for the reply! Your ideas are great. Its just the matter of getting the federal government to cough up the money to pay the workers that is difficult.

@ Neil Halliday,

Thanks.

Now I get it.

And now I also see that the bold line should end at point A-subJG, in the middle, because that is just the unemployed who are between jobs. Giving that UR as the end of the trajectory.

The line is the trajectory. But, I still think that there will be some price rises. Not sure if they would meet the ‘on-going’ part of the definition of ‘inflation’. They would still hurt some people for some time, at least hurt them a little.

Actually it ought to be much closer to the zero UR axis, and not be in the middle there.

The MMT approach is not so easy to grasp for mainstreamers. The only reason unemployment exists is because of government. The government has created It. That is why the JG makes sense. If you go further then you realize that unemployed are already in public sector one way or another.

Bill said (quoting his own book):

Although I am, and have been for some years, a strong supporter of MMT, in the context of discussions about the JG, I do sometimes worry about the presentation of JG jobs versus jobs in “the private sector”, as is done in the quoted text above.

As though these were the only alternatives, namely permanent private sector jobs, or (implied temporary) public-sector JG jobs.

As though, in other words, there was no such thing as permanent public sector jobs. Clearly that is not the case, even in capitalist USA, and definitely not the case in the UK, where we have even had socialist and quasi-socialist governments at times. And even after years of Tory governments (including Thatcher and her imitators), we still have a relatively large and significant public sector, and having a public sector job is still regarded as a fairly respectable thing (except of course in the pages of the more rabid right-wing press).

In the light of this, I would rather like to see the quotation above to be expressed something like:

(The amended wording is still not ideal, but it’s hard to find alternatives that do not either over-simplify the situation or involve (even more) cumbersome wording. There is a slight complication in that, I’m fairly sure I have read Bill writing that if someone wanted to stay in a JB job for the rest of their working life, then they should be free to do so. So in that sense, JG jobs could be “permanent jobs”. Whereas I get the impression that the major American writers on MMT (such as Randy Wray and Warren Mosler) envisage JG workers “returning to the private sector” as soon as there is a recovery, and the private sector re-expands. Apologies if I have mis-represented them).

…

I do have a bit of a problem with the JG itself, and I was reminded of this by the last sentence of the quoted text above. My problem is around the subject of inflation. Now some people who support MMT seems to think that the MMT way of curing inflation is by taxing away money from the economy (and I have been guilty of thinking this way myself on occasions). However, I think Bill has written that he does not believe taxation to be a particularly good way of controlling inflation. Another approach is for the government to cut back on its own public spending (not always easy to do, in practice, but let’s say that it does happen). I presume that Bill / MMT proponents would definitely not recommend cutting back on JG jobs, so at least in theory, those jobs would be sacrosanct.

So the government would have to cut back on other forms of public spending. This would not necessarily involved cutting down permanent public sector jobs (although it might). It might mean, for example, cutting back on public building works, which would probably lead to some unemployment in the building trade, which is normally carried out by private contractors. Unemployed builders would of course, be free to seek employment in the JG scheme, albeit with probably serious loss of income.

I admit that I probably do need to go back and read some of Bill’s articles on inflation.