It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Seize the Means of Production of Currency – Part 1

Last week, Thomas Fazi and I had a response to a recent British attack on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) published in The Tribune magazine (June 5, 2019) – For MMT. The article we were responding to – Against MMT – written by a former British Labour Party advisor, was not really about MMT at all, as you will see. Instead, it appeared to be an attempt to defend the Labour Party’s Fiscal Credibility Rule, that has been criticised for being a neoliberal concoction. Whenever, progressives use neoliberal frames, language or concepts, it turns out badly for them. In effect, there were two quite separate topics that needed to be discussed: (a) the misrepresentation of MMT; and (b) the issues pertaining to British Labour Party policy proposals. And, the Tribune only allowed 3,000 words, which made it difficult to cover the two topics in any depth. In this three-part series, you can read a longer version of our reply to the ‘Against MMT’ article, and, criticisms from the elements on the Left, generally, who think it is a smart tactic to talk like neoliberals and express fear of global capital markets. I split the parts up into more or less (but not quite) three equal chunks and will publish the remaining parts over the rest of this week.

Introduction

The Tribune recently published the unequivocally titled Against MMT (June 3, 2019) – written by James Meadway, former advisor to shadow chancellor John McDonnell.

The sub-heading of his article was:

Modern Monetary Theory disorients the Left by peddling simplistic monetary solutions to complex problems of political power.

He joins a swathe of mainstream economists and policymakers – Kenneth Rogoff, Larry Summers, Paul Krugman and others – who have viscerally attacked Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Incredibly, Republican Senators have even proposed a resolution in Congress denouncing MMT – the first-ever resolution proposed against an economic theory.

More surprising is the fact that MMT has also been the subject of fierce criticism by left-wing economists and commentators such as Doug Henwood and Paul Mason.

In common with these other ‘critiques’, Meadway’s article is really not about the core body of work known as MMT at all.

Rather he seeks to defend the credibility of the neoliberal-inspired Labour Fiscal Credibility Rule by setting out a ‘straw person’ version of MMT and then rehearsing the standard accusations that MMT proponents are naive about inflation, exchange rate collapse and the might of global capital.

In doing so, Meadway demonstrates that he has not grasped (or refuses to grasp) the subtleties of MMT.

In a political sense, his arguments repeat those that Chancellor Dennis Healey used when he lied to the British people in the mid-1970s about the Government running out of money.

These falsehoods eased the path for Margaret Thatcher, created the space within Labour for the highly damaging Blairite years, and constrain the current British Labour leadership’s conception of what is possible in terms of economic policy formation.

In the last year or so, the critiques of MMT have accelerated as its public profile has risen, partly due to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s promotion of the ideas in relation to her endorsement of a ‘Green New Deal’ (GND) proposal.

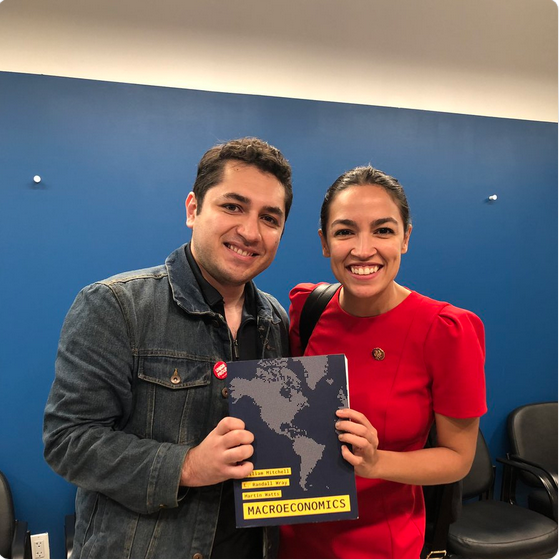

Here is AOC receiving her copy of our (Mitchell, Wray and Watts) new MMT textbook – Macroeconomics – from her advisor Andrés Bernal.

There was also a bit of coverage about the book in this recent Bloomberg article (May 31, 2019) – A 600-Page Textbook About Modern Monetary Theory Has Sold Out.

MMT not only threatens vested neoliberal interests in politics but also challenges the hegemony of mainstream macroeconomists who have been able to dominate the policy debate for decades using a series of linked myths about how the fiat monetary system operates and the capacities of currency-issuing governments within such a system. MMT exposes these myths.

An MMT understanding allows us to break out of the illusory financial constraints that for too long have hindered our ability to imagine radical alternatives and to envision truly transformational policies, such as the Green New Deal, in the knowledge the issue is not whether we can afford a certain policy in financial terms but only whether we have enough available resources – and political will – to implement it.

This is massive paradigm shift. It’s no surprise that the establishment’s reaction has been so vicious.

Our response here is to Meadway’s Tribune article, but it applies equally to other recent attacks published elsewhere.

To set the record straight we start by providing a straightforward understanding of what MMT actually is – rather than what its critics often accuse it of being.

What is MMT?

At the outset, it is important to note that MMT should not been seen as a regime that you ‘apply’ or ‘switch to’ or ‘introduce’.

Rather, it is a lens which allows us to see the true (intrinsic) workings of the fiat monetary system.

It helps us better understand the choices available to a currency-issuing government and the consequences of surrendering that currency-issuing capacity (as in the Eurozone).

It lifts the veil imposed by neoliberal ideology and forces the real questions and political choices out in the open.

An MMT understanding means that statements such as the ‘government cannot provide better services because it will run out of money’ are immediately known to be false.

Such an understanding will change the questions we ask of our politicians and the range of acceptable answers that they will be able to give. In this sense, an MMT understanding enhances the quality of our democracies.

MMT is agnostic about policy. bar its preference for an employment buffer rather than an unemployment buffer to discipline inflation.

In general, it makes no sense to talk about an “MMT-type prescription” or an “MMT solution” as Meadway does.

To make that MMT understanding operational in a policy context, a value system or ideology must be introduced. MMT is not intrinsically ‘Left-leaning’.

A Right-leaning person would advocate quite different policy prescriptions to a Left-leaning person even though they both shared the understanding of how the monetary system operates.

We can see that in the recent debates in the Japanese Parliament where conservative politicians and Communist party members have invoked MMT understandings to argue against sales tax hikes designed to reduce the fiscal deficit.

In the simplest possible terms, MMT describes and analyses the way in which ‘fiat monetary systems’ operate and the capacities that a government has within that system.

Currency sovereignty requires a government to issue its own currency, floats it on international markets, and only issue liabilities in that currency.

Such a government has a monopoly over currency issuance. Here it is important to note that MMT distinguishes between ‘currency’ and ‘money’, a nuance that escapes Meadway – viz his accusation that MMT is wrong to assert that government is a monopoly issuer of currency because “most money is created by private banks when people take out loans”.

Banks cannot create currency. But the implications of this takes us beyond the remit of this response.

The task of such a government is to provision itself with real resources to deliver its socio-economic program.

It creates a demand for its otherwise worthless currency by requiring all tax liabilities to be extinguished in that currency.

The government spends its currency into existence through the purchase of goods and services from the non-government sector (so-called government spending) which provides the non-sector with the funds necessary to pay its tax obligations.

The consequence of this logical ordering of events (spending to fund taxation) is that currency-issuing governments do not have to ‘fund’ their spending and can never run out of currency.

Saying otherwise is as stupid as saying that a football game has to stop 3 minutes into the second-half because the scoreboard has run out of points to post!

It also means that a currency-issuing government can purchase whatever is available for sale in that currency, including all idle labour.

The appearance of idle labour, for example, is evidence that the government has not spent enough relative to its tax take – so taxes are too high and/or spending is too low.

In turn, this means that the unemployment rate is not a ‘market’ phenomenon or a choice of individuals (the mainstream dogma) but a political choice of government. The ideology of mass unemployment is thus exposed by an MMT understanding.

Further, a currency-issuing government is not like a household, which uses the currency and faces intrinsic and binding financial constraints on its spending.

The household analogy is popular in mainstream macroeconomics but provides us with zero understanding of what the capacities of the issuing government are. Unlike a household, the constraints on government spending are not financial but real – limited by the goods and services that are available for sale.

The core MMT developers do not, as Meadway claims, consider a “hierarchy of currencies” with the US dollar at the top nor do they assume that non-dollar currencies have only limited currency sovereignty.

All currency-issuing governments enjoy monetary sovereignty as outlined above.

We should not conflate the capacity to purchase available goods and services with some ability to provision an economy with adequate real resources, as Meadway seems to do.

Issuing one’s own currency doesn’t make a nation ‘rich’. A nation with limited access to real resources either locally or through trade will still remain materially poor.

Sovereignty, though, means the government can use its currency capacity to ensure the resources that are available are always fully employed in one way or another.

In this way, Meadway is wrong when he claims “If you can’t issue the dollar, MMT isn’t going to work.” That is a fundamental misunderstanding.

MMT also doesn’t assume that a nation, as Meadway claims:

… can choose to run enormous deficits, and the whole economy can sustain extraordinary trade deficits …

Typically, the non-government sector (households, firms and ‘rest of the world’) desires to spend less than its flow of income – that is, there is an overall desire to save.

If unchecked, such a leakage from the income-spending stream will cause firms to reduce production and lay off workers.

The role of government net spending in this context is to fill that savings gap to avoid recession.

In normal times for any nation running an external deficit, the government has to run fiscal deficits up to size necessary to maintain spending sufficient to keep all resources fully employed.

A nation such as Norway, with strong export revenue, can still provide first-class public services and infrastructure while its private domestic sector achieves its desired saving, while its government runs a fiscal surplus. But that situation is rare.

In general, MMT uses the sectoral balances (or flow of funds) approach, which tells us that the government sector’s deficit (surplus) is always equal to the non-government sector’s surplus (deficit).

Further, if there is an external deficit (exports less than imports plus net financial flows), then the government balance necessarily has to be in deficit for the private domestic sector to be in surplus – that is, for the private domestic sector to be able to save overall.

If this condition is not met, growth will necessarily have to be sustained by an expansion in private domestic debt, which is an unsustainable basis for growth.

Since Britain is not likely to generate large external surpluses in the foreseeable future, it follows that the only way private debt – and the power of financial institutions over society – can be brought under control without driving the economy into recession is for the government to run persistent and substantial fiscal deficits.

This reminds us that steering the economy towards full employment, something socialists should arguably aim for, doesn’t just require ‘fine-tuning’ – some extra spending when the economy slumps – and public investment.

It requires constant control of its movement through fiscal policy.

Fiscal deficits ‘in themselves are neither good nor bad’, as the economist Abba Lerner, one of the precursors of MMT, wrote in the 1940s.

Any assessment of the fiscal position of a nation must be taken in the light of the usefulness of the government’s spending program in achieving its national socio-economic goals and the savings desires of the non-government sector.

This is what Lerner called the ‘functional finance’ approach.

Rather than adopting some target fiscal outcome defined in financial terms (for example, some deficit as a percentage of GDP), governments should spend and tax with a view to achieving ‘functionally’ defined outcomes, such as full employment.

Fiscal policy positions thus can only be reasonably assessed in the context of these macroeconomic policy goals. So the real limit to government deficit spending is therefore the capacity of the economy to absorb it without generating runaway inflation.

But it should be emphasised that all spending carries an inflation risk if it outstrips the capacity of the economy to respond to it by producing goods and services. Government spending is not unique in that respect.

Now, governments voluntarily impose accounting rules on themselves, which might require them to have sufficient funds in their account at the central bank where ‘tax’ revenue is recorded, before they can spend.

If they desire to spend more than the ‘available’ funds, a rule may require them to ‘cover’ the deficit through debt issuance.

While these accounting smokescreens elicit the impression that the taxes and borrowing fund the spending, nothing could be further from the truth.

As noted above, the ability to pay taxes come after spending.

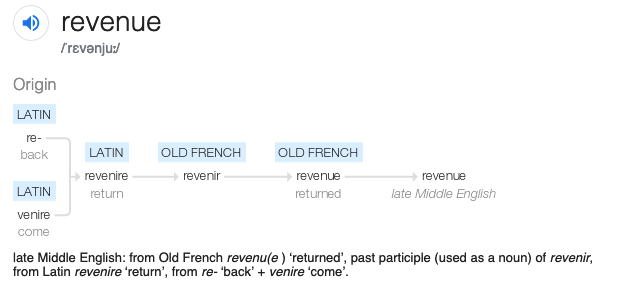

The etymology of the term ‘revenue’ is outlined in the following graphic:

Taxes are thus government spending that is returned to the government!

Further, the funds that the government ‘borrows’ are, in an accounting sense, just the prior spending that has not been previously taxed.

And, if the non-government sector didn’t want to hold any of their wealth portfolio in the form of government bonds (debt), the government’s central bank always has the option of stepping in and buying either new or existing bonds by crediting relevant bank accounts.

There is no financial constraint on this activity. And most central banks around the world have purchased huge quantities of government debt in the context of quantitative easing. The Bank of Japan is continuing to do this on a massive scale.

While mainstream macroeconomists (like Meadway) try to link ‘monetary operations’ (taxes, bond sales) with ‘funding operations’, the reality is that government spending occurs in the same way irrespective of the accompanying transactions (such as bond issuance).

Governments just instruct their central banks to credit bank accounts (MMT calls this adding reserves) via the digital system.

Invoking terms such as “government-printed money”, as Meadway does, to describe this process is fundamentally wrong.

There is no ‘printing’ going on.

The ‘printing’ term is, of course loaded, and creates a frame that ‘mad’ government officials are cranking up printing presses and pumping the notes into the economy willy nilly.

Further, while taxation is just the ‘debiting’ of bank accounts, it would be nonsensical to think of taxation as ‘unprinting’ money.

Does this mean that taxes are not necessary?

… to be continued.

Conclusion

We will return to the issue of taxes and inflation in Part 2 tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I try to read your article everyday but most times I just skim, so I had a little grin when you complained about “only 3,000 words” to rebut the article. I wish you had a blog called “Gist Bill” 😉

Bill, I read The Conversation each day. Most of the articles are written by University lecturers and professors. It has a huge amount of readers. The economic writers are just writers of the neoliberal viewpoint. With your permission I would like to suggest to The Conversation that you write an article on MMT. Is that okay?

Dear Patricia (at 2019/06/11 at 10:31 am)

I do not write for the Conversation. Their editorial policies have been unethical and they have published articles lying about MMT and refuse to withdraw them.

best wishes

bill

Okay Bill. But with the support of many on this website we will continue to push MMT on The Conversation and question the reasoning of those neoliberal economist who do post there.

Bill,

Above you wrote, “It requires constant control of *its* movement through fiscal policy.”

.

This is one of my pet peeves. The use of a pronoun that doesn’t have a clear antecedent.

The *its* in that sentence confuses me. What is it the movement of which needs to be controlled?

It is made more confusing by the use of the word “it” twice in the sentence.

@Steve_American

My understanding of this would be:

“It ( i.e. the steering of the economy) requires constant control of its (i.e. the economy’s) movement.”

@Mr Shigemitsu,

OK, you do know that one Neo-liberal attack on MMT is that the US Congress is not capable of the required constant “steering” of the economy [aka, tax changes]. Bill has said repeatedly that he is against giving technocrats control over such steering because he doesn’t trust them not to be captured by Neo-liberal thinking.

There is also a Constitutional problem. The Constitution only gives Congress the power (with laws) to change the tax rates.

I suppose that Congress could give the Fed. Res. Bank the power to adjust a special surtax with a tax rate of from 0% to a maximum of 5% added on to every income tax amount and withholding. Come to think of it, the withholding is pretty simple but the final tax owed would be a nightmare to calculate. [ For example, suppose that there was a constant 3% surtax for the entire year, in this case you would owe 3% more than “normal” at the end of the year. So, calculate your tax normally and then multiply that amount by 1.03 to get your final tax owed. If the surtax rate is changed in mid-year twice it would be more complicated.] This doesn’t address the problem of technocrats being in charge even if it is fairly limited.

.

@Steve_American & Mr Shigemitsu

Used with a comma, rather than a period and “it”, with “but”, the meaning may become clearer:

“This reminds us that steering the economy towards full employment, something socialists should arguably aim for, doesn’t just require ‘fine-tuning’ – some extra spending when the economy slumps – and public investment, but requires constant control of its movement through fiscal policy.”

Control of the economy is the essence of government (of any political description)

Of course control of the economy lies at the foundation of a democratic government just like it does in a communist (or despotic) one; it is just a question of how that control is exerted.

In a democratically organised one an appeal must be made to the voters as to what will produce the most desirable outcome – a right-wing party will frame its argument in terms of how the “abstract” nature of markets can be relied on to produce prosperity, with the accent being put on individualism , while a left-wing party will frame its appeal to highlight the purpose of equality, with access to a comfortable and secure lifestyle for everyone and national income re-distribution based on the the imposition of taxation.

The fairness of left-wing policies appears to have an overwhelming advantage, yet they have never generated a sustained a majority following. You may argue that this merely represents the deceit involved in political influence. But even where left-wing governments have prevailed workers have risen up against a government perceived as implementing policies that place whole communities at a disadvantage – the Bridgend car plant is the latest such example (would the Labour party be able bear the burden better than a Tory party sheltering behind the abstract forces of market economics).

MMT is now widely accepted as an accurate lens on economic activity. But we are still a long way from proving that it consistently works in practice.

@Steve,

We all suffer from useless and incapable politicians, it’s true.

Nevertheless, someone has to be Keeper of the Flame, and Bill and the core MMT group’s descriptions and prescriptions are always there, ready and waiting for competent politicians to understand and implement.

Laissez-faire market neoliberalism is doing an increasingly dreadful job of driving our economies with no hands on the steering wheel; at some point soon the balance will tip over once again in favour of active government, and one can only hope that cometh the hour, cometh the wo/men, smart and capable enough to know what’s needed to be done.

The MMT narrative continues to improve and its influence continues to expand as a result. The ‘means of producing money’ concept is a good example. This shift from the ‘means of production’ which is hopelessly anchored to Stalinist tyranny, is a breakthrough in my opinion. MMT advises It is what you decide to ‘fund’ that is most important. It is the values one applies that informs what the spending will fund.

I’m currently involved in a little twitter exchange with Simon Wren Lewis who has just published a piece defending his (and Portes) dismal fiscal rule from the charge of being neoliberal.

I asked him if the slowest recovery ever and 0.25% rates weren’t enough to reach the ZLB, then what would? He said it had been reached. I asked for when and the minutes and pointed him to the August 2016 ones.

He said it was ‘widely known’ in 2009 that 0.5% was the effective lower bound and that it had been reached.

I took a look at the March ’09 minutes (when the drop from 1.0 to 0.5% was made) and there was no mention of a bound being reached or considered. I’ve since found a couple of later reports from the BoE (from 2012/13) that said that the effective lower bound had been reached then, but the point stands that the MPC didn’t appear to think it had – or at least didn’t say as much in their considerations then (and a quick googling of MPC reports & variations of the year&zero & effective & lower & bound of subsequent sets of minues didn’t show anything until, guess when, August 2016 when they miraculously found that the ZLB was actually lower than 0.25% (without stating when they had decided this level or what it was prior to this).

He’s currently asking what my point is again, but it should be obvious — the MPC will jump through all sorts of hoops to avoid handing power to a Labour Chancellor – especially if that person was someone like Chris Williamson.

Bill wrote: “We can see that in the recent debates in the Japanese Parliament where conservative politicians and Communist party members have invoked MMT understandings to argue against sales tax hikes designed to reduce the fiscal deficit.”

Quite interesting. Do you have any links to English-language web pages reporting this?

Dear Adrian Kent (at 2019/06/11 at 9:53 pm)

They are all in denial. I have clearly pointed out to them, with links to the evidence from the Bank’s own press releases/minutes, that at no point during the crisis did the MPC indicate that it considered monetary policy in Britain to have reached a point where it could no longer be effective.

That is on record. Fact.

To dispute that is to live in a dream world.

Which is why the Fiscal Credibility Rule is deeply flawed. The MPC would never have ceded control to a Labour Treasury during the GFC so they could suspend the Rule. Which means the Treasury would fail to reduce the debt ratio from rising in that 5 year period if a serious recession struck. Which means the Rule would be violated. Which means Labour would be discredited.

The problem is that egos are involved and they have to deny reality because otherwise they have to admit they are mistaken. Their response to be is to claim I am stupid.

I tried to get John McDonnell to understand the reality but his advisor at the time just kept interrupting with his nonsense.

Bad luck for British Labour.

No point even debating them.

best wishes

bill

Dear James E Keenan (at 2019/06/11 at 10:17 pm)

I discussed the issue and provided translations from the Diet record of debate here – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=42385

best wishes

bill

For what it’s worth, I have adopted this rebuttal technique for doubters and opponents of MMT: MMT is a theory that cannot be disproved, because it is not an hypothesis but an explanation of the real framework of today’s economics scraped bare of the layers of falsehoods from the mainstream.

It excludes such devices as the household analogy and borrowing for currency creation. Money creation comes from deficit spending which both extinguishes the debts and creates the currency simultaneously and free of liability.

I can add that the Congress action in ordering bonds through Treasury auctions is redundant as there are no outstanding debts to match, as the deficit is already being paid down all the time.

Dear Bill (following your comment at 22:25):

I remember that you had pointed this out directly to the Fiscal Rule proponents, but couldn’t find the link.

Bizarrely now though, SWL has concluded our little twitter exchange by suggesting that I take my (our) complaints regarding the MPC’s proven zero-lower-bound-gymnastics up with the MPC members themselves. It’s as if I was the one who was suggesting we hand them even more power than they already have.

Best wishes,

Adrian.

John, your rebuttal is not quite correct logically. Any empirical theory can be falsified in principle. So far, MMT has been corroborated every time it has been ‘tested’. MMT just happens to be true in the sense that it accurately characterizes certain aspects of reality, which the mainstream, neoliberal theories do not. Because MMT is true, it is able to explain how the monetary system works, which the mainstream theories can’t do (because they are false).

What is a fundamental reason the mainstream theories are false? Basically because they begin from unrealistic, indeed false, assumptions and from there all their subsequent errors follow. There are basically three of them: the rational agents hypothesis, the efficient markets hypothesis, and the ergodic axiom (a contention that the future will be largely like the past and indeed the present). The ergodic axiom directly contradicts Keynes’ principle of (ontological) uncertainty — there is no additional knowledge that can reduce the uncertainty. MMT does not make these mistakes. These are in addition to the analogical errors that you point out.

Re Steve American and tax rates:

I believe Bill has written that the preference is not to be constantly adjusting tax rates but to rely mostly on ”automatic stabilizers” that adjust quickly according to the state of the economy. If need be tax rates could also be modified. An example of a program that could work as an automatic stabilizer but that is not always thought of in that way is infrastructure development. There could be a list of pre-approved shovel ready projects across the country and as the economy slowed they would be activated. If the economy heated up too much they could be slowed down.

Re Bill’s comment that ”egos are involved”.

Yes I am sure egos are a problem. However I believe more important is that the political decision has been made not to appear too radical and be subject to attacks by the Conservative Party that Labour is fiscally irresponsible, etc. Therefore whatever rational arguments Bill and others bring are irrelevant and vacuous justifications will be produced to counter them. This is truly unfortunate.

We faced a similar situation in Canada during our election in 2015 when the ostensibly social democratic NDP argued for balanced budgets while the more centrist Liberal Party argued for budget deficits. The NDP was ahead in the polls at the time but not for long. After they proposed budget deficits the Liberals cringed in fear that the NDP would also propose deficits but NDP analysis was too neoliberal to allow it to do so. Shortly after the election the Prime Minister (Justin Trudeau) stated in an interview that the NDP’s failure to also call for a budget deficit is what won the elections for the Liberals.

The reality is most people don’t care about the fiscal deficit but do care about the nasty effects of austerity. It is true the rhetoric must be carefully honed not to trigger the wrong public reactions but this is quite doable in my opinion.

Keith, Labout squandered about two years which they could have devoted to altering and attacking the mainstream narrative. But, instead, they reinforced it by showing that they followed it as well. It is their own fault that they are in the pickle they find themselves in.

Bill, small typo:

I think you missed out “-government” when you typed “non-sector”.

bill

Correct but they can create purchasing power to bid up the price of real resources and thus consume precious politically acceptable price inflation space that might otherwise be used for the common welfare.

Of course even 100% private banks with 100% voluntary depositors could create SOME purchasing power with relative safety but not nearly so much as our current heavily privileged usury cartel with captive depositors.

Banks create credit which enable credit-worthy individuals and organizations to obtain currency. NO bank uses its depositors’ money for loaning to others. This is part of the loanable funds theory, which is false.

Correct but nevertheless having captive depositors increases the banking cartel’s ability to safely create deposits and thus compete for real resources with defict spending for the general welfare.

Of course enough privilege from government/the Central Bank can eliminate the need or desirability for banks to have ANY depositors but otherwise captive depositors increase the ability of banks to safely create deposits.

Andrew, deficit spending by the government can be carried out whatever the banks do and it can outcompete for real resources. If a set of banks are operating a cartel, then this can be broken up by the government. I am speaking about a reasonably ideal case here, of course.

Depositors do not enhance or detract from the ability of a bank to provide loans, which is what creates deposits. I don’t understand the first part of your sentence.

“deficit spending by the government can be carried out whatever the banks do and it can outcompete for real resources. ” larry

Sure – by driving up prices and thus using up precious politically acceptable price inflation space.

“Depositors do not enhance or detract from the ability of a bank to provide loans,” larry

Only because they are privileged by government/the Central Bank. Eliminate those privileges and banks would be reserve constrained – especially since ALL citizens could have debit/checking accounts of their own at the Central Bank itself, not just depository institutions, so that draining reserves from a bank would be as simple and safe as transferring funds from one’s bank to one’s account at the CB.

“A nation such as Norway, with strong export revenue, can still provide first-class public services and infrastructure while its private domestic sector achieves its desired saving, while its government runs a fiscal surplus. But that situation is rare.”

Yes, mainly because Norway hit the natural-resources jackpot with North Sea oil, as did the UK. Norway set up a sovereign wealth fund, whereas the UK splurged it all on paying a huge army of unemployed. Was Monetarism a pre-cursor to MMT?

@Andrew, as Bill has stated many, many, times – all spending carries the risk of inflation. The government, however, can limit the spending on a particular resource in the private sector by either taxing it or straight-up outlawing it. The banks cannot.

“- all spending carries the risk of inflation.” Matt B

Of course it does but why should government privilege private sector purchasing power creation for the sake of the private welfare of the banks themselves and the rich at the expense of potential fiat creation for the common welfare?

@Nick Turner

What use to Norway, or its people, is its Sovereign Wealth Fund?

Other than as an overseas sump to store petrodollar earnings that, if converted to Krone and spent in Norway, would lead to massive inflation, because, with a population of 5m people, its capacity to absorb all that spending without overheating the economy is severely limited.

It is permitted to domestically spend by law around 1% of its SWF annually, IIRC, but of course it doesn’t even need the money in the SWF because, as we here all know, as the monopoly issuer of Krone, the Norwegian govt can already spend whatever it likes in Norway, up to the limit of its real resources.

The UK with a larger economy has been able to absorb its oil income, but its govt has equally, since at least 1971, also been able, as sovereign currency issuer, to spend as many pounds as it wished, up to the economy’s real capacity limits too. It has just chosen not to.

De-industrialising and replacing jobs with dole and sickness benefits was a deliberate and vandalistic political choice by Thatcher – having a SWF for UK oil earnings would be/have been neither here nor there, because, as we know, the UK govt is never currency constrained, but real-resource constrained instead.

Chris Willaimson understands MMT and agrees with it. I got into conversation with him and Richard Werner, who was trying to convince us that Government does not create money. Is he a shill for the banks? https://twitter.com/Clementtomorrow/status/1137335414350651392

re – Mr Shigemitsu

Wednesday, June 12, 2019 at 19:03

“De-industrialising and replacing jobs with dole and sickness benefits was a deliberate and vandalistic political choice by Thatcher”

Where did you get that accusation from – while she was certainly outmoded in her Victorian and Quaker beliefs in balanced budgets, elitism and old-fashioned philanthropy, she was correct in sharing the widespread view that Britain was in long-term (and barely reversible) industrial decline.

The role of monetarism that she supported and indeed encouraged inevitably led to a rising and painful period of unemployment that she was prepared to tolerate in her quest to turn the economy round. Such was the impact of conventional economic wisdom at that time.

But “deliberate” and “vandalism” are descriptive of someone who wanted to permanently damage the economy and its workers. That opinion is at variance with the known facts and her British ideals and heritage.

@gogs

They say MMT is politics-neutral, so I suppose one must expect to encounter right wingers on the journey as well as left.

Believe what you will about Thatcher… but having lived through her contempt for, and wilful destruction of the working class and their interests – deliberate and vandalistic works quite well enough for me, thanks.

re – Mr Shigemitsu

Thursday, June 13, 2019 at 5:15

Let’s have a bit of perspective.

I refer below to an article in the Newcastle (UK) Journal describing Margaret Thatcher’s role in bringing Nissan to Sunderland, providing thousands of jobs directly and indirectly to a region annihilated by declining industries.

http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/revealed-how-margaret-thatcher-saved-6464068

I would describe Thatcher’s involvement as highly constructive – indeed, a display of leadership. For all her humanitarian blind spots her resolution sometimes outweighed her faults.

And talking about leadership, we might shortly see MMT being asked to define its principles in practical terms as it is now firmly embraced by the various propaganda frames of Green New Deal (GND), some of whose proposals have been emphasised as urgent and top priorities.

Does this mean that governments are to be encouraged to create expenditure to mobilise the under-employed in such tasks ; how is this to be done, and by whom, and in the required timescale. We are constantly reminded that there is such a lot to do to safeguard the climate – so. are workers to be displaced in order to fulfill these urgent GND commitments (where does JG fit into this); and what about the costs, How do we achieve all this expenditure within acceptable inflationary boundaries without additional re-distributive taxes applied.

Let us have some policies to debate and vote on, some practical leadership to drive the momentum.

“[…] and what about the costs, How do we achieve all this expenditure within acceptable inflationary boundaries without additional re-distributive taxes applied.”

Since a good portion of current consumption is credit-financed, at least a part of spending wouldn’t really be “new” but substituted (actual income instead of payday loans to get by). Additionally, there is no reason to believe that supply could’t handle an uptick in demand as a result of living wages for the poorer half of Americans. I wouldn’t expect re-distibutive taxes to have any considerable effect on inflation since it would hit those whose propensity to spend is already low. Still, they should be part of any sensible plan in order to prevent asset-price-inflation and to reduce the excessive political influence that accumulated wealth carries.

“[…] how is this to be done, and by whom, and in the required timescale.”

The government already has implemented at least one massive “deficit spending programm” in its ridiculously bloated military. Last time I checked, it was the biggest employer in the US with about 2.8 mio employees. The army of working poor employees at Walmart reaches an impressive 2.3 mio, but next in the list would be Amazon with <600k. This clearly shows that governments can mobilize ressources, including idle or underpaid workers, if they so desire to. In the short term at least, government is unlikely to employ those who actually carry out the work directly and would almost exclusively comission private contractors. However, it can enforce JG-standards as a requisite for application.

In regards of the required timescale I think there is a post around this blog about the vastly underrated dynamics of fiscal policy. Also, I don't see why government should be considered inherently less capable or competent than the "free market". If the latter was so efficient and superior, it would have already dealt with environmental threats instead of having to be pressured into action by public outrage. Coca-Cola changing the color of their label from red to green is what "market-based" solutions yield. Finally, even limited and inefficient action is better than no action at all and that is what the critics of the GND seem to have to offer.

This all is without even considering if high un- or underemployment, high levels of private debt and the deprivation of services for most citizens in order to mantain historically low rates of inflation is morally justifiable.

@gogs,

I’m not willing to get into an endless argument with you about Margaret Thatcher, but she played a huge role in that annihilation in the first place!

Other European countries are still involved in the kind of heavy industry that was destroyed in the UK, including shipbuilding and motor manufacturing, and they’re not necessarily dependent on the whims of FDI either (e.g. see Honda’s recent decision to repatriate manufacture of certain models from the UK to Japan, post EU-trade agreement).

We’re still reaping the whirlwind of her legacy, which certainly under the current government, as well as previous New Labour incarnations, has stubbornly refused to die.

Neither am I particularly impressed by Prime Ministers with humanitarian blind spots – which, to be fair, has been almost all of them.

I grew into adulthood through those depressing and damaging years, was delighted when she was forced to resign as PM by her own party, and very glad to see the back of her when she finally died off – you won’t persuade me, I’m afraid, and it will be a waste of of time for both of us.

But, certainly, if you wish to admire her, please go ahead…

RE: GND: “Let us have some policies to debate and vote on, some practical leadership to drive the momentum.”

Yes, I agree with you there.

Mr S, I agree with you about Thatcher. Alan Walters, an American economist was her principal economic advisor in the early years and he was a monetarist, what is now a neoliberal. And she revered Milton Friedman. She may not have been as fanatical as the current group, for instance, she refused to sell the PO, but she could be just as delusional as they seem to be, such as believing that new industries would arise from the ashes. Had it not been for the Falklands War, she might have been out a lot earlier than she was, so unpopular was she at that time.

I would love to see the end of the Tory party. It looks as though Johnson might well win the so-called election. Mathew Parris, Rafael Behr, and Max Hastings (not necessarily a great guy himself, but it could be argued that it takes one to know one) have nothing good to say about him. Here is Hastings:

“Boris is a gold medal egomaniac. I would not trust him with my wife nor – from painful experience – my wallet. It is unnecessary to take any moral view about his almost crazed infidelities, but it is hard to believe that any man so conspicuously incapable of controlling his own libido is fit to be trusted with controlling the country.

His chaotic public persona is not an act – he is, indeed, manically disorganised about everything except his own image management. He is also a far more ruthless, and frankly nastier, figure than the public appreciates.”

There is a study by two profs of politics in the south who have data from yougov that show that most of Johnson’s support is, it would appear, comprised of departees from Ukip, those who joined the party from 2016. Not a good sign.

re – larry

Friday, June 14, 2019 at 2:31

I think you mean Alan Walters, British economist

Sir Alan Arthur Walters was a British economist who was best known as the Chief Economic Adviser to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher from 1981 to 1983 and again for five months in 1989. en.wikipedia.org

re – Mr Shigemitsu

Thursday, June 13, 2019 at 21:20

“Other European countries are still involved in the kind of heavy industry that was destroyed in the UK,”

To demonstrate my unbiased attitude to left versus right ideologies I refer below to a fine example of a Polish state shipbuilding organisation that developed a successful competitive strategy that won a large share of world demand:

https://hbr.org/1995/11/how-one-polish-shipyard-became-a-market-competitor

“… but it is hard to believe that any man so conspicuously incapable of controlling his own libido is fit to be trusted with controlling the country” (Max Hastings, quoted by Larry).

Lloyd George? (nicknamed “the goat”).

Judged purely on political achievement, among the greatest of prime ministers.

(I’m not a fan of “Boris” BTW).

re – Mr Shigemitsu, concerning earlier correspondence

And so to the competitive process and its consequences for Capitalism (and Socialism too)

Whether enterprises are controlled by Private Ownership or a National State, the role of the market place determines not only the success or failure of the organisation but also influences the living standards of a nation’s population.

You will recall from my last note that the Szczecin shipyard had managed a profound turnaround to its fortunes. Since then, Amem Communication produced a report in June 2005: http://www.amem.at/pdf/AMEM_Communication_018.pdf which described the Polish shipbuilding industry in rather bleak terms –

“Almost all shipyards have been facing the threats of bankruptcy and those that survived so far have been given repeatedly massive direct and indirect financial aid by the Polish Government”.

It goes on – “Despite a drop in employment, going down from 70.000 people in the 1980s to 37.000 by the end of the 1990s and 16.000 in 2004, the shipbuilding industry remains an important segment of the national economy, with another 80.000 employees in the marine equipment supplier’s industry”

By 2015 the situation was being described in similarly pessimistic terms;

https://www.total-croatia-news.com/business/1098

– croatia by then was the second largest shipbuilding nation in Europe. “More than 92 percent of ships have been contracted at shipyards in the three leading shipbuilding countries of the world: China, South Korea and Japan. The European shipbuilding industry holds a share of just 1.62 percent,….”, also ” It is interesting that Poland, after the restructuring ten years ago, has ceased to be a strong player in the European shipbuilding.”

There is a general attitude among left-wing supporters that once an industry is placed within the control of the state everything will be fine and any troubles will, by comparison with those associated with Capitalism, be mere tribulations, especially those concerning worker welfare.

Whilst a competitive world prevails there will always be upheavals; unfortunately the last to see these traumas coming will be the workers themselves (commercial secrecy being just one reason).

best wishes

Gogs

Mr. S and Gogs:

“We had the back of Maggie’s hand

Times were tough in Geordie land”

-Why Aye Man, Mark Knopfler

Howay man, vote for that that gadgie

wey, aye,man, just get my hinny

Bill. Very enjoyable read.

This is directed to Gogs. I think I just caught you in a lie. Explain to me why it isn’t.

“The fairness of left-wing policies appears to have an overwhelming advantage, yet they have never generated a sustained majority following. You may argue that this merely represents the deceit involved in political influence. But even where left-wing governments have prevailed workers have risen up against a government perceived as implementing policies that place whole communities at a disadvantage – the Bridgend Car plant is the latest such example(would the Labour party be able to bear the burden better than a Tory party sheltering behind the abstract forces of market economics.”

The first sentence – you impugn deceit, and then you lie. You say that left-wing policies only appear to be fair. Then you go on to say that they have never enjoyed a sustained majority. You say never.

I look at Sweden. Socialism. Almost complete membership of workers in unions. Again Norway, Denmark. Even Venezuela, under near global embargo and subversion from without. Look at Vietnam. They defeated US. Communist China.

The second sentence – you lie again – by false association. You place left-wing government in power and closing the Bridgend car plant, and placing people unfairly at a disadvantage. I thought they had a conservative government now. Besides that, it was a decision by Ford, to close the plant. But see, by deceit, you place the left-wing as inflicting damage to workers, placing them at a disadvantage. Disadvantage? Do you mean seeing and treating working people as inferior. That’s something that goes with the wealthy and the powerful. Yea. And this is just the latest injustice inflicted upon the working people by the do-gooder left wingers. So you impugn their morality. You imply left-wingers are repeated hypocrites.

Third sentence – you come back to some truthfulness and acknowledge that this has happened under a conservative government. It’s like a paint job to provide the appearance of tempered acknowledgement, but covering, glossing over corruption.

This is the type of thing Milton Friedman was so good at – false associations, half-truths, outright lies.

How do you like my analysis of you?

Yok,

“I look at Sweden. Socialism. Almost complete membership of workers in unions. Again Norway, Denmark.”

I am interested in how you define socialism.

Would you mind giving me your definition?

re – Yok

Wednesday, June 19, 2019 at 14:44

I did not intend to impugn Socialism by use of the word “never” – on reflection it was too definitive; I was suggesting British Socialism, for all its philosophical aims, cannot truly be relied upon to successfully remedy economic upheavals that place whole communities in jeopardy, and that is perhaps one reason why an electorate may become less supportive.

That is where the deceit comes in – politicians (of any party) are inclined to withhold the brutal truth whilst offering some alternative solution (even if that is almost impossible to deliver). The demise of the coal-mining industry is a prime example – the beneficial effects on the environment could hardly be paraded as justification for shutting a whole community down, let alone the effect of a competitive market .

And, it is in terms of old-style industrial communities that we saw the most destructive consequences of change. Shipbuilding is another prime example; these tightly-knit concentrations of populations, living in oppressive conditions and working in harsh environments encouraged tribal instincts of survival; historic communities so constrained, their bonds so strongly entwined, that voting patterns become determined by a sense of oppression and an appeal for change.

It doesn’t matter which political regime (I gave Bridgend as just another example) has to handle these upheavals, unless some preparation is in place to smooth the transition, workers will experience major inconvenience – some of which may be permanent.

I note that in the Bridgend case offers of re-skilling and other undertakings are to be part of the process of change.

I have said before that I have no particular bias towards Socialism or Capitalism. They are both guilty of (some necessary) deception. If there is a difference, I naturally assume that a Socialist government has to frame its appeal in humanitarian imagery more than a Conservative regime, because the latter bases a good deal of its philosophy on the operation of a competitive market economy.

This seems to me to raise questions about what kind of economic society we are targeting – and whether a more caring society is willing to forego some degree of wealth formation (increased GDP and productivity) in accomplishing a more humanitarian goal.

Creating this kind of society also depends on the re-distribution of income (taxation), political persuasion and a much different attitude to consumer desires and their effect on economic forces.

I trust this explanation puts things in a more acceptable light.

Henry Rech. My definition of socialism: to place under the control, or authority, or responsibility, or ownership of the public, where the public is able to function in a meaningful way, meaning where the public through democratic means is able to effect the direction of government policy.

Gogs. My point wasn’t to defend socialism. My point was to show that your statement was false. You used the term left-wing. I used Sweden because the people are happy with the government, they haven’t opposed the government, Sweden has socialism, and I consider socialism a left-wing outlook. So your statement that left-wing governments are always overthrown by the people who “recognize injustice” when they see it is false.

re-Yok

Thursday, June 20, 2019 at 0:12

This article in the Guardian (see below ref) following the 2018 election in Sweden suggests a different interpretation to your own.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/14/sweden-remains-in-political-limbo-after-all-votes-counted

I pick out one particularly insightful paragraph: “The prime minister had earlier said he believed the election result marked the end of Sweden’s traditional system of political blocs, which has been severely destabilised by the steady rise of the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats.”

It seems that some political groups are willing to through governments out whether a grievance is justified or not.

I should like to emphasize that I do not lie except in error of facts or interpretation.