Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Australian government’s fiscal statement – pitiful and irresponsible election ploy

This morning, I declared that I was angry on a multitude of levels. I am part of a local community group that is fighting greedy developers, corporate real estate speculators and a compliant local council over an outrageous abuse of planning. That really gets me mad. NSW, the state I reside in mostly, just re-elected a corrupt conservative government, largely because the former leader of the Labor opposition couldn’t keep his hands out of the clothing of a female journalist and his successor mouthed off about Asians taking our jobs. Bloody hell, the Labor Party had it won, and then lost it. Angry. Then we go a little higher in the hierarchy to the fiscal statement (aka ‘The Budget’) which the conservative Australian government brought down last night. And outrageous piece of chicanery and economic malpractice. What is worse is the head of the Federal Opposition’s policy think tank – the John Curtin Research Centre – put out an Op Ed late last week accusing the Conservative government of not doing enough to “address debt” and shirking “serious, structural repair” and not having a public “debt ceiling”. What the F&*k! Did the IMF write this piece? The ‘think tank’ claims it is a “social democratic think-tank dedicated to developing ideas and policies for a better Australia”. Yes, folks that is what social democracy means in Australia – neoliberalism! More on the fiscal statement in what follows. And if I wasn’t already hugely mad enough with all of that, I read that the British Labour Party is desperate for Britain to stay in the Single Market – lock-stock-and-barrel. What! This is the most advanced expression of neoliberalism. I guess it is consistent with their ridiculous ‘Fiscal Credibility Rule’ that keeps the current Labour Party firmly in the Blairite tradition – scared to death of those creeping, amorphous financial markets and so lacking in confidence that they hang on to the grim lies that Dennis Healey introduced to Labour narratives in the mid-1970s. Mad as hell about that! And then we get to Brexit central. The people voted in a majority to LEAVE! It was a correct decision for the long-term, progressive future of Britain. The cosmopolitan liberals couldn’t cope with the idea of, maybe, having to queue up at the border of the 27-nation European Union when they go on their next ski holiday. Their answer – vilify the voters who knew the EU was the exemplar of neoliberalism and do everything to stop the departure. Enter a totally incompetent Tory government to oversee the departure and you get an almighty mess. For once I agree with the former Bank of England governor – Britain should get out next week with no deal and announce a major fiscal stimulus to keep the economy moving while adjustment occurs. So I am glad I have a full head of hair! Then I read another plethora of anti-MMT pieces and my humour improved. A bit of comedy is always important!

Background to last night’s fiscal statement

1. Australia’s GDP growth rate was 0.2 per cent in the December-quarter 2018 and falling fast – see Australia national accounts – growth plummets, per capita recession (March 6, 2019).

The only things driving growth has been declining household consumption growth and some state government public infrastructure projects. The former is declining sharply now because of flat wages growth, record debt levels and falling wealth on the back of plunging real estate prices.

The latter is finite and will exhaust soon.

Business investment is lagging.

2. Australia’s labour market is weak with employment growth regularly around zero, a bias towards casualisation, and an unemployment rate stuck around 5.2 per cent and underemployment around 8.5 per cent – see Australian labour market – weakness continues, January was a blip (March 21, 2019).

3. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) has been around 13 per cent for some years now. . There were a total of 1,748 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

4. Australia’s participation rate is below the pre-GFC levels as is the Employment-to-Population ratio.

5. Over the course of the current cycle (since February 2008), teenagers have lost 96.1 thousand full-time jobs (net).

6. Wages growth is at record low levels and real wages growth has been flat to negative over the last several years, while corporate profits have boomed – see Reliance on household debt and a lazy corporate sector – a recipe for disaster (September 6, 2018).

7. In the March-quarter 2016, the wage share was 55.2 per cent. By the June-quarter 2018, it had fallen to a low of 52.2 per cent.

8. Australian households are carrying record levels of debt, while real estate prices are plunging (around 10 per cent falls in last year). Recent ABS data shows that “Household wealth (net worth) decreased 2.1% in the December quarter 2018, driven by real holding losses on land and dwellings, and financial assets” (Source).

9. The unemployment benefit payment has not adjusted in line with poverty line estimates for some years and recipients are being forced by both sides of politics to live well below the accepted poverty line.

See – ‘Progressive’ groups in Australia captured by neoliberal ideology (September 18, 2018).

10. Australia’s external sector remains in deficit, as it has been since the 1970s, averaging around 3.5 per cent of GDP, which means that if the government sector runs a fiscal surplus or a deficit below 3.5 per cent of GDP, the private domestic sector must be spending more than it receives overall.

11. A major policy initiative of the previous government – the National Disability Insurance Service – which aimed to fund items as basic as wheelchairs for families who cannot afford them – has been severely underfunded by the current Federal government who put a cap on the public employees who would support the scheme. Long delays have resulted in people not being able to access any funding or support.

The government has held back the ‘underspend’ and claimed it against their fiscal bottom line (which has been moving towards surplus).

12. Inflation is persistently below the Reserve Bank’s lower targetting bound and shows no signs of increasing.

13. The most recent data shows that the Federal government fiscal balance has shifted from a deficit of $A10.1 billion (0.5 per cent of GDP) to an estimated deficit of $A4.2 billion (0.2 per cent of GDP) between 2017-18 and 2018-19 (end of period is June).

It is estimated by the Government to record a surplus of $A7.1 billion (0.4 per cent of GDP) in 2019-20.

Look back over the 13 background facts and ask yourself which is the outlier.

Facts 1-12 are all directly related to Fact 13, which is what I want to talk about next.

The fiscal statement – consider these graphs

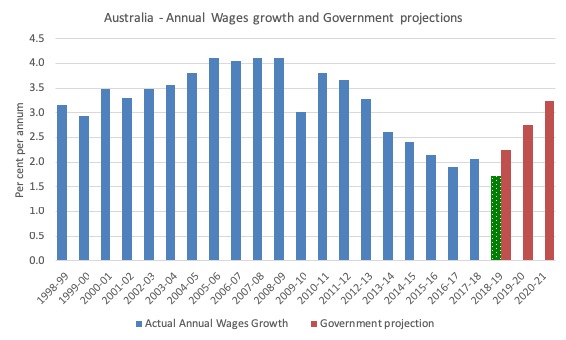

Consider the following graphs. They are two different views of wages growth in Australia, which is now at record lows in relation to the preferred Australian Bureau of Statistics measure the Wage Price Index.

The first graph the actual annual growth (blue bars) since the 1998-99 financial year up until the present period (the 2018-19 bar in green is the average of the September and December quarters only).

Actual wages growth has been trending down for several years now as the impact of the sustained levels of labour underutilisation take their toll.

The red bars are the estimates and projections in Statement 2: Economic Outlook – published on Tuesday by the Government.

The Government wrote:

As economic growth strengthens and spare capacity in the labour market continues to be reduced, wage growth is expected to pick up to 23⁄4 per cent through the year to the June quarter 2020 and 31⁄4 per cent through the year to the June quarter 2021. Growth in the Wage Price Index was 2.3 per cent through the year to the December quarter 2018, its equal strongest outcome in more than three years.

Note also that the Government is projecting that the unemployment rate is set to remain at 5 per cent out to 2020-21, which is well above the pre-GFC low of 4 per cent.

And the participation rate is projected to be constant over the period to 2020-21 – again this is a depressed forecast.

While the fiscal estimates make no projections about underemployment, it remains a huge problem in Australia and is likely to remain high over the projection period.

Considering the facts I presented at the outset, the reasonable question is: Why will the Wage Price Index recover so strongly and so quickly?

The reasonable answer is that it will not – the dynamics are just not going to be there.

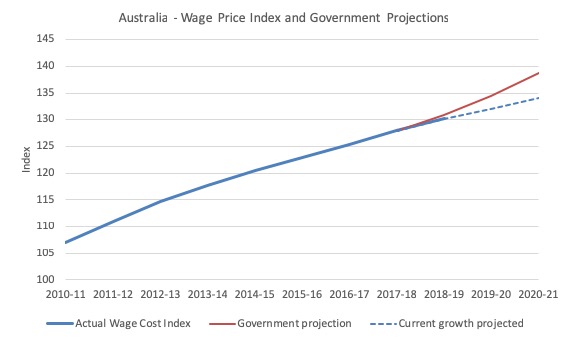

The second graph shows the Wage Price Index itself (since 2010-11). The red line is the fiscal projections for the wages growth, while the blue dotted line is a reasonable projection based on recent growth (with no material change in labour market conditions projected).

You can see there is a credibility issue here in terms of this key Government projection.

Why does this matter?

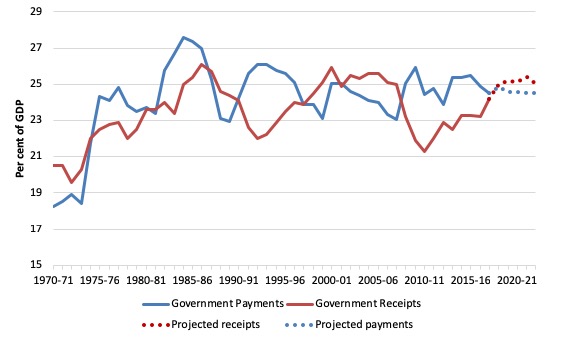

Consider the following graph, which shows government payments and receipts as a percentage of GDP from 1970-71 out to 2022-23

The dotted segments are the fiscal statement projections.

You can see that while payments are projected to fall to 24.5 per cent of GDP, receipts are projected to rise from the current 24.2 per cent to 25.4 per cent in 2021-22 and drop back to 25 per cent in the final year of the projections (2022-23).

Hence the projected fiscal surplus in 2019-20.

Even though the Government is offering tax cuts to individuals and corporations, it is still forecasting solid taxation receipts in the coming years.

This is based on two key projections:

1. The (unbelievable) projected rise in wages growth (as noted above).

2. Unrealistic real GDP growth forecasts – expected to rise to 2.75 per cent by 2020-21 despite the current annualised growth rate being 0.8 per cent.

Will any of that happen? Not likely.

Which means the fiscal estimates are just political artifacts designed to win a nearly unwinnable election and have little grounding in reality.

Regressive Tax Cuts and Trickle Down returns

The electioneering in the fiscal statement is clear.

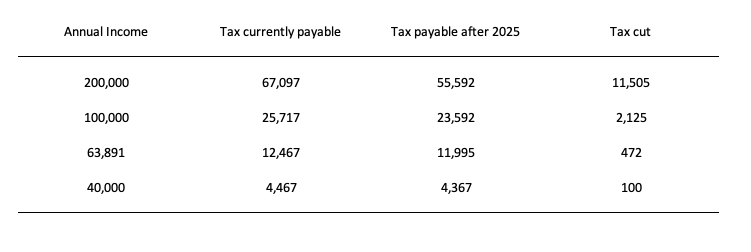

First, not much has been said of the plan to virtually flatten progression in the income tax system.

The Government says it will have a lowest tax bracket of 30 cents in the dollar in place by 2024 and that 94 per cent of all workers will be in that bracket – earning between $A45,000 to $A200,000 per annum.

What does that actually mean?

The Treasury Department has provided a – Tax relief estimator – which allows us to make some calculations which are shown in the following Table:

Conclusion: The flattening of the tax structure will deliver massive benefits to the high income cohorts and the lower income workers will get very little relief at all.

The fiscal system becomes much more regressive as a result of this flattening. And there are no fiscal measures likely to offset that increased tax regression on the spending side.

The Government is also claiming that these tax cuts will drive growth.

Remember ‘trickle down’ economics.

These tax cuts are unlikely to increase labour supply (one of the tenets of supply-side trickle down) but they are unlikely to boost overall spending much, given the big winners have much lower marginal consumption spending propensities

Further, the claim that it is better to get the tax cuts than a wage increase are flawed even in basic arithmetic.

A given percentage tax cut delivers much lower income boost to workers than a similar increase in wages.

These tax cuts will not redress the damage that the flat wages growth is bringing.

The contractionary bias

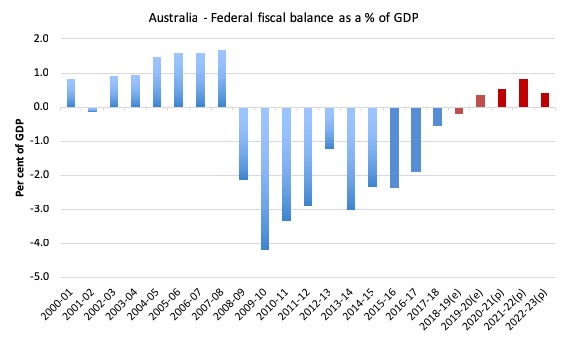

The fiscal statement released last night by the Treasurer has the following forward estimates for the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP. The graph starts in 2000-01 and goes to 2023-23

The red bars are the latest projections from the current Government as outlined in Tuesday’s statement.

The fiscal deficit is projected to fall from $A10,141 million in 2017-18 to $A4,162 million in the current financial year (2018-19). By 2019-20, a surplus is estimated of some $A7,054 million, increasing thereafter.

The Treasury estimates show the government will increasingly reduce its contribution to growth in the remaining years of the forecast period until 2022-23, when the fiscal surplus is projected to be 0.4 per cent of GDP.

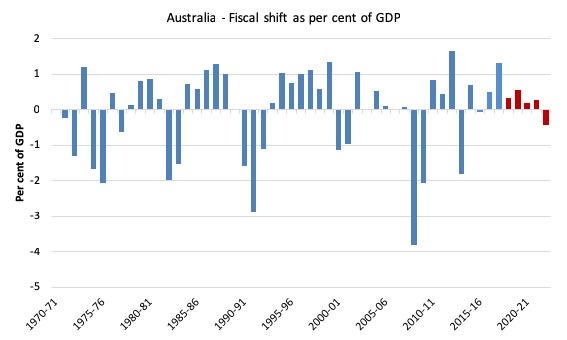

The fiscal shift from one year to another is the change in the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP changes. It is the result of two factors – the fiscal balance itself (in $As) and the value of nominal GDP (in $As).

The following graph shows the recent history (from 1970-71) of fiscal shifts up to the end of the projection period (2022-23).

The biggest fiscal swing in the previous conservative government’s tenure was in the financial year 1999-2000 (a shift of 1.4 per cent).

A sharp slowdown in the economy followed that contraction and the fiscal balance was in deficit two years later (2001-02).

The Australian economy only returned to growth because the Communist Chinese government ran large fiscal deficits themselves as part of their urban and regional development strategy. That spurred demand in our mining sector.

The largest fiscal shift in the sample period shown was the second-last fiscal statement from the previous Labor government in 2012-13 which was equivalent to 1.7 per cent of GDP. They prematurely withdrew the fiscal stimulus bowing to the assault from the neo-liberal press and commentariat about the dangers of deficits. It was a moronic and damaging retreat.

A major slowdown followed and dented the recovery from the GFC that had been spawned by the fiscal stimulus in the previous two years.

That Labor government was obsessively trying to achieve a fiscal surplus in 2013-14 and was blind to the reality that the private domestic sector was not going to fill the spending gap left by the retrenchment in net government spending.

The result – which was totally predictable – the economy took a nosedive, tax revenue fell even further and the fiscal balance moved further into deficit with unemployment rising.

The current conservative government was elected in September 2013 (and subsequently reelected in September 2015).

In Tuesday’s fiscal statement, the forward estimates imply a continued tightening of fiscal policy (red bars) although the 2017-18 shift of 1.3 per cent of GDP was very damaging.

The fiscal shift in the current year (2018-19) is projected to be 0.3 per cent of GDP, and this increases in the following year (2019-20) to 0.6 per cent of GDP, then 0.2, 0.3 with some easing prjected in 2022-23 (smaller projected surplus).

With a slowing economy overall, record levels of household debt and flat wages growth starting to impact on household consumption spending and business investment still floundering this level of fiscal drag is unsustainable.

Unless there is an extraordinary pick up in private spending or net exports then the economy will not achieve the underlying growth assumed the Government will not achieve these fiscal projections.

The problem is that in trying to achieve them, they will inflict further damage on an already weak economy.

Taking the basic facts I listed at the outset as a whole, the obvious conclusion is that there needs to be a fiscal deficit of more than 2 per cent of GDP right now and that should be sustained into the future period (indefinitely).

As I show next, that will help the private domestic sector reduce its unsustainable debt exposure, which is now driving the slower growth in household spending.

The private sector’s debt position is set to worsen

The economic predictions, which underpin the fiscal statement and are contained in Budget Paper No.1, show that the Treasury is forecasting the following outcomes:

1. The fiscal deficit for 2018-19 of just 0.21 per cent of GDP reducing a surplus of 0.4 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, a surplus of 0.5 per cent, 0.8 per cent and 0.4 per cent of GDP in the subsequent years in the projection.

2. The current account deficit is projected to be 1.75 per cent of GDP in 2018-19, rising to 2.75 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, and 3.75 per cent of GDP in 2020-21. The average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2016-17 has been 4 per cent of GDP. It is hard to see how the current year’s estimate will be achieved.

So what does that all mean in terms of the sectoral balances?

We know that the financial balance between spending and income for the private domestic sector equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

The sectoral balances equation is:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector to net save (S – I > 0).

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to accumulate financial assets.

Expression (1) can also be written as:

(2) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting.

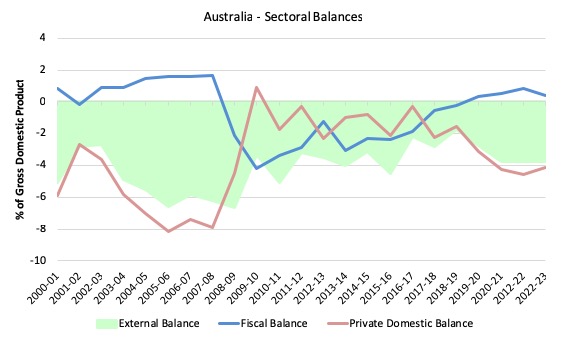

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2022-23, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in ‘Budget Paper No.1’.

The vertical black line demarcates the actual from the projected data. I have assumed that the external position in 2021-22 and 2022-23 will be the same as the Government’s estimate for 2020-21.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

So it becomes clear, that with the current account deficit (green area) more or less projected to be constant over the forward estimates period, the private domestic balance overall (solid red line) is the mirror image of the projected government balance (blue line).

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit. This not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to start the process of rebalancing its precarious debt position.

That process has been interrupted by the renewal of the fiscal surplus obsession since 2012-13.

You can see the red line moves into surplus or close to it. The long-run average private domestic deficit is 2.4 per cent of GDP and was achieved largely when the household saving ratio was between 10 and 16 per cent and private investment in capital formation was strong.

That was a sustainable position because the capital investment was boosting GDP growth and providing returns to keep the debt in check.

The fiscal strategy outlined by the Government last night continues the trend – as the graph shows – for the private domestic sector to once again to be accumulating debt as it progressively spends more than its income.

The growth strategy of the Government, even if they will not admit it, is to rely on squeezing the liquidity of the non-government sector and forcing the latter to accumulate increasing debt commitments in order to maintain spending.

That is exactly what we saw before the crisis – growth becomes reliant on private debt buildup.

The whole nation is transfixed on fears that the government debt in Australia is too high – courtesy of all the scaremongering that has been going on. But nary a word gets mentioned about the dangerous private debt levels.

The reality, however, and this is now being revealed by the national accounts data, is that household’s have probably reached their limits for credit, and, combined with the flat wages growth and falling wealth, have started to rein in their consumption spending growth.

In other words, the Government’s strategy will fail – badly.

Conclusion

I haven’t had time to write about the climate change issues in the Government’s fiscal strategy. Suffice to say they are basically climate change denialists.

I also haven’t written about the unemployment benefit scandal.

Nor have I said anything about the appalling responses from the Opposition Labor Party – about how the projected surplus is not big enough etc.

The foresight of the Government and the care for the people it is elected by is severely exposed in this fiscal statement.

It has been framed to improve the election prospects of the Government and has limited economic coherence.

I am really angry about it.

I guess I will now tune into the British Brexit news!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Point 10 needs “receives in income overall” added to the end.

“Announce a major fiscal stimulus” is not very likely with either possible post-Brexit government .

There won’t be much to smile about in the British Brexit news I’m afraid Bill. True, a certain amount of comedy mixed in with all the tragedy.

As we speak, I believe Jeremy Corbyn is trying to convince Theresa May of the virtues of a permanent customs union, and a dynamic relationship (whatever that means) with the Single Market.

Do you think that all this Brexit hoo-haa will end up like the Y2K flap of 1999?

Much ado about nothing. Already one simple option has come the proposal by the Bank of England

to crash out and do a massive fiscal stimulus.

@John Doyle: Yes and no. As those of us who worked in IT at the time know all too well, the Y2K problem was a real problem which took a lot of advance work by a lot of people in order to solve, and ensure planes didn’t fall out of the sky, etc.

In the case of Brexit, even regarding so-called “crash out” Brexit, I believe a lot of work has been done. Whether it will prove to be enough remains to be seen. But already we know that the Irish Border question didn’t need to be the major problem that so many people made it out to be. If you listen to Jacob Rees-Mogg, the problem with the “Backstop” is not actually the Irish border, but that the EU could use the Backstop as an excuse to force us into doing certain other things that we might not want to do in an ideal world. Since I started actually listening to him, and not just falling about laughing at his name and mannerisms, I’ve learned to have a lot more respect for him, even if his politics (on everything except Brexit) are the exact opposite of mine.

In 1992 I first came to the UK to study in Cambridge. At the time the country was marred by decades of trade union and old Labour rule. The economic situation was hardly better than that of the socialist GDR, which had just collapsed a few years earlier. Then in the 1990s, Thatcher\’s reforms started to bear fruit. The speed at which the quality of every day life improved in the UK was breathtaking. Having seen the devastations that socialism causes first hand, I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw the rise of the UK in the 1990s. Now they have old Labour Jeremy Corbyn threatening nationalizations and all sorts of old Labor policies. In my view Corbyn is a much bigger threat to the UK than Brexit. It is sad to see that people have such short memories.

Despite RuddSwann initially nodding and smiling to ken Henry in 08/09, it now seems evident that they had little idea what was, to paraphrase Stacy, (Fr Gavin & Stacy)… occurrrin’ . It seems they’re about to stumble into Government, and be faced with similar circumstances to ’08. We don’t know yet, of course, how bad it will be, but we seem reasonably assured that they will be, pro tem, economically incompetent. Maybe Henry could reprise his role.

It is a sad state of affairs when our government and opposition both are reading from the same playbook. Focussing on the elusive surplus at the expense of those in society most in need. They all need a good dose of reality.

Thanx so much, Bill, for your scholarly and erudite critique of the senseless waste of our economy to which both sides of politics looks like condemning Australia. My flabber is well and truly gasted that there is NO media questioning about the need for a surplus! Even the ABC is guilty of feckless interrogation of politicians and the “expert” economists they interview. When will they start talking to you, Bill?! 🙁

Yet, today we see the devastation just a few decades of unrestrained neoliberalism causes..

It’s quite disturbing, to see the same ideology applied to fiscal matters being promoted by most parties almost globally.

@Dirk

“In 1992 I first came to the UK to study in Cambridge. At the time the country was marred by decades of trade union and old Labour rule.”

Thatcher had been PM for over a decade then.

In fact, since 1935 Labour had held the PM office for about 17 non-consecutive years by the time your glorious memories set in:

Clement Attlee 45-51

Harold Wilson 64-70 and 74-76

James Callaghan 76-79

Hardly “decades”.

You obviously have fond memories of younger years and are entitled to your own opinion, but not to your own reality.

@Scott

The “Team Pepsi vs Team Coke” electoral dynamic under the almost universal cognitive capture of the neoliberal “there is no alternative” (TINA) regime is evident not only in Australian politics but across the West. I would encourage you to investigate Mark Blyth’s work about this, which explores the death of what he calls the “cartel parties” as austerity increasingly drives the distressed bottom end of the electorate to “populist” alternatives of both the right and left.

@Dirk

Your description of the changes experienced by the UK since Thatcher is mildly amusing in its Panglossian assurance. It’s rather more monstrous in its casual blindness to the suffering of wide swathes of the UK citizenry over that time, and no doubt representative of what passes for thinking among the UK elite on the evidence of their recent behaviour.

Dirk

Wednesday, April 3, 2019 at 21:58, said:-

“In 1992 I first came to the UK to study in Cambridge. At the time the country was marred by decades of trade union and old Labour rule”.

I think you must have been studying in Cambridge Mass. not Cambridge University. Either that or you were a bit disoriented. The “decades of trade union and old Labour rule” as you tendentiously describe them had in fact ended (if they can truly be said ever to have started) thirteen years or more before then, when then-Chancellor Denis Healey succeeding in persuading the great majority of his (Labour) Cabinet colleagues that full-blooded monetarism tied to a – totally needless – IMF loan was the only answer to Britain’s economic difficulties (thus paving the way for Margaret Thatcher’s “there is no alternative” (TINA)).

At the same juncture, Prime Minister Harold Wilson was rejecting (without having read it, nor intending to) Tony Benn’s cogent argument for – guess what – a perfectly viable even if, for many, unpalatable alternative which unquestionably *was* old Labour through and through. It was those events which marked Labour’s decisive turn towards the Right – in 1977 (IIRC).

At the time the weight of public opinion was almost certainly with Healey not Benn, and that was duly borne out when the Tories under Thatcher won the 1979 election and subsequently went on to junk large swathes of Britain’s industrial base, sell off the nation’s patrimony to smart operators looking to make a quick buck before bailing-out with their wallets bulging with the proceeds, and generally to turn the UK into a financialised casino-banking husk of its former self (my turn to be tendentious!).

With hindsight, Benn was right and Healey – and of course Thatcher – wrong.

Uncannily, there’s an echo of that debate being heard now in connection with Brexit. Today’s “Bennites” – the ones who passionately believe that if only Britain could summon-up the necessary guts it could (albeit after knuckling-down and and enduring a potentially torrid year or two) come out the other side, leaner maybe but also stronger and fitter, and having reclaimed its freedom of action. Ironically, they’re mostly to be found – apart from a few brave, far-sighted, souls on the Labour’s extreme Left wing – amongst the reviled Tory Right-wingers. (Not so surprising in fact if one remembers that David Davies (for example) was a prominent campaigner alongside Tony Benn against British EU membership).

It’s not your fault that you were born too late to experience the only near-socialist government this country has ever had, and that you were brought up without a proper understanding of 20th century British history, especially political history.

For people like me who were fortunate enough to be born into the tail end of that government, once the NHS was already established, and homes were beginning to be built, and industry beginning to thrive, with low unemployment, this grew into what is now looked back on as a golden age, by people with proper perspective.

It started to go wrong due to lack of proper investment by conservative (and Conservative-minded) leaders of industry, and a Tory government that started to do away with the “post-war consensus”, followed by a Labour government which fell for the myths of Monetarism.

It is your fault however, that you evidently have not studied this history through the lens of Bill’s many articles, and his book “Reclaiming The State”. Or if you did read them, you evidently had your mind closed.

@Doyle – just to reiterate Mike’s comment, no one in the IT industry shares this view of Y2K. If anything, you should take the current security deficit as indicative of the sort of result that was expected from not addressing Y2K.

I note in the sectoral balances graph that the CAD remains in elevated negative territory, despite the currently favourable trade balance. Is this all interest on foreign borrowings, or is there a large out flow of investment?

Dear Brendanm (at 2019/04/04 at 4:58 am)

The Current Account is the sum of the Trade Account and the Income Account. For Australia, the income account is always in deficit due to repatriation of profits and debt repayment.

best wishes

bill

Dear Dirk (at 2019/04/03 at 9:59 pm)

You would have experienced something quite different if, like me, you had studied in one of the industrial cities of northern England, with proximity to mining towns. Being cosseted in Cambridge among the elites in the early 1990s is hardly a good grounding for what Thatcher did to Britain in the late 1970s.

Did you go out to Fallowfield, Salford, Moss Side, Inner Liverpool, the villages in the Leeds valleys? I doubt it. Those places were devastation zones and have never recovered.

And, I prefer not to have this sort of standard neoliberal commentary on my blog. There is a plethora of it elsewhere.

best wishes

bill

Keep blogging Bill! This blog inspires so many readers to pursue a different path and learn about MMT. In years to come this blog will be the primary record of the economic theory that ended the neoliberal era.

Re Brexit and economic stimulus. You can print all the money you want but so long as there is even one item essential for your economy that cannot be purchased in your currency, you are stuffed.

Bill,

You’ve stated

“Taking the basic facts I listed at the outset as a whole, the obvious conclusion is that there needs to be a fiscal deficit of more than 2 per cent of GDP right now and that should be sustained into the future period (indefinitely).”

Why do you recommend more than 2 per cent when the current account deficit is 3.5 per cent?

I think there is so much disinformation about deficits and surpluses, that I feel it my duty to add my little bit, hoping I do not add to the confusion.

A budget surplus is in fact a shrinkage of the money supply – less money is put into the economy than is taken back out.

A surplus can occur in a number of ways: by the government indulging in an austerity program and spending less on goods and services, or by increased taxation, or by issuing government bonds. In the current election climate where extra spending is always promised, and where reducing taxation is almost mandatory, this leaves only issuing more government bonds, which temporarily drain money from the economy to achieve the surplus.

Issuing government bonds is of course called “government debt”, so obviously this government debt will increase if you want a surplus. But although there is much hand-wringing over government debt, it is in itself is no real problem as the bonds can be very easily and quickly retired.

But there is something else of much more real concern. If the money supply has shrunk, and if we want to maintain or even increase the level of production in the economy, the remaining money has to work harder, that is, the velocity of money flowing through the economy has to increase.

How does this happen? Simply by commercial banks increasing the amount of money they loan, recirculating existing money at an ever increasing rate, which is to say increasing private debt.

So to push for a surplus is to increase both government debt and private debt. But whereas extinguishing so-called government debt is relatively easy, paying back private debt is not.

Not only this, but asset-backed private debts are often bundled by the banks into further tradeable products to feed the frenzy of finance capital, which is very unhealthy, and some say lead to the GFC.

The result is that regarding a surplus as something good is a very strange for those who think that debts are bad, which is what most neo-liberal economists seem to believe.

Why on earth would the Labor Party go along with this, unless as a temporary expedient to get elected? The trouble is, we know it would be not so temporary.

Dear Gregory Bradley (at 2019/04/04 at 9:58 am)

Very insightful.

Who said anything about “print(ing) all the money you want”? Certainly not me. I said fiscal stimulus. Quite a different proposition.

I think you might best learn some MMT before commenting.

best wishes

bill

Fantastic article. Why do we not have this kind of sectoral balance analysis as part of regular economic commentary?

In NZ we are all told that an OCR cut is on the way – and that that will supposedly save the day here and prevent an Australian-style slow down.

But I look at the high levels of household debt here and our supposedly progressive government’s surplus obsession (unambitious austere spending plans) plus our similar current account deficit and conclude that an OCR cut will be like pushing on a string.

The political goodwill Adern currently has should be used to do some useful public spending.

Bill excellent wrap up and summary of the Federal budget and Australia’s current macroeconomic position. I like the new format for the blog, much better than the old one.

In 1992 I first came to the UK to study in Cambridge. At the time the country was marred by decades of trade union and old Labour rule. The economic situation was hardly better than that of the socialist GDR, which had just collapsed a few years earlier. Then in the 1990s, Thatcher\’s reforms started to bear fruit. The speed at which the quality of every day life improved in the UK was breathtaking. Having seen the devastations that socialism causes first hand, I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw the rise of the UK in the 1990s. Now they have old Labour Jeremy Corbyn threatening nationalizations and all sorts of old Labor policies. In my view Corbyn is a much bigger threat to the UK than Brexit. It is sad to see that people have such short memories.

Shakes head in disbelief.

This was 13 years after the election of Mrs Thatcher.

The sad part of the Brexit drama is that much of the House of Commons has swallowed the doom and gloom scenarios about leaving on WTO terms. Rejecting No Deal seems to be about the only thing that commands a majority at the moment.

Some sort of compromise (Norway, Customs Union, or the like) or a revocation of Article 50 look inevitable to me.

@Gregory Bradley – really not sure what you’re getting at. Are you suggesting that the rest of the world will immediately decide not to do any business with the world’s 5th largest economy simply because it has extricated itself from the EU? That the flow of all goods into the UK will end as abruptly as a light being switched off?

You’ll have to forgive me for considering that to be more than just a little far-fetched.

Here is a thought that has troubled me for some time now. The arguments presented by MMT are rational. As we all know it is a description of financial reality and not a theory. Any sufficiently intelligent and reasonably knowledgeable individual must see it. It therefore follows that the resistance is not rooted in misunderstanding. We get it and most of our opponents get it too. I would argue that we should dismiss ideology as an explanation as well. Ideology is a diversion, a distraction designed to confuse and manipulate a weak ignorant mind. Therefore presented as an argument to an experienced opponent it is bound to fail. This leads to a conclusion that very likely both sides already know that MMT is accurate. This also means that our opponents nearly always argue in bad faith. This includes politicians, policy makers, professionals, social media outlets, bloggers etc. That in turn begs the question. What is the point? If one’s goal is to change the mind of the opposition then it is probably impossible. The opposition is driven by unrelated circumstances. It is also true that most of those with any practical use to us, people in positions of power and influence, have most unfavorable public views of MMT. The ultimate question is what is the best strategy in the environment where everyone who matters is privately in agreement yet publicly in opposition?

Dear lavrik (at 2019/04/04 at 3:31 pm)

Thanks for your comment.

But where did you get the idea that MMT was just a “description of financial reality and not a theory”.

I make statements of consequence almost every day on this blog – that is, statements that predict or assess outcomes.

Where do they come from? From causal understandings. Where do they come from? From theory. MMT – the T is about that.

And we all exercise ideology. It is not confined to right-wingers. I have a very coherent ideology that I express when I make value statements in my work.

best wishes

bill

Dear HermannTheGerman

“Clement Attlee 45-51

Harold Wilson 64-70 and 74-76

James Callaghan 76-79

Hardly “decades”.”

You forget that the various conservative governments between Attlee and Thatcher never managed to reverse any of the major labor policies. The TUC’s power grew relentlessly throughout the post-war period to the 1980s. Hence, it was “decades” of trade union and labor rule that had brought the UK to the brink of collapse by the 1980s.

Bill,

What would you have said to Leigh Sales interview question to Bill Shorten tonight that increased wages will simply lead to businesses putting their prices up?

Dear Tim (at 2019/04/04 at 7:45 pm)

Thanks for your enquiry.

At present, businesses have been pocketing the productivity growth in excess of real wages in the form of increased profits.

As the sales environment flattens, they are struggling to maintain market share and are likely to reduce their mark-ups back to something more normal if labour costs rose more in line with productivity.

It is a very difficult environment for firms to be pushing up prices.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill,

While we’re on the subject of the budget, to what extent is government spending self-financing? I fear my logic may be the left-wing equivalent of tax cuts paying for themselves, but the government budget seems to be treated like a black hole, where the money goes in and disappears, while in reality most of that spending will come back in taxes.

In particular, what about spending on non-discretionary expenses, like cancer treatment. At the scale of the economy the same amount of money is being spent regardless if it comes from the individual or the government, but if the individual is the one paying then they have less money left over to spend and come back to the government in taxes.

Bill (at 2019/04/04 at 4:21 pm),

You are right. What I meant to say was that at its foundation MMT is a set of observations about the mechanics of various monetary arrangements. Please correct me if I am wrong, I don’t think that at its ‘core’ it has any unverifiable postulates. Yes, there are many derivative claims. One may also attach value judgments to those claims thereby sometimes setting up a good vs evil melodrama.

Thanks.

Dirk you’re right, the period between 1945 and 1970 was one of Butskillism.

The word is an amalgam of Ran Butler and Hugh Gaitskill (Labour and Tory chancellors at one point).

The Tories had to triangulate Labour by adopting a watered down version of its policies during this period.

Conservative governments were pushing in a similar direction to worker’s parties during this period.

Edward Heath’s government tried to break the post war consensus by going neoliberal in 1970 but it had to perform a U turn (hence Mrs Thatcher’s famous “the lady’s not for turning” speech.)

The same thing happened around the world. The Truman and Eisenhower regimes embraced the post war consensus.

Menzies triangulated Labor in Australia by steeling its policies.

Thanks for this analysis, Bill,

Regarding your sectoral balances chart, where is the dataset for the red line – private domestic balance?

Thanks,

Alan A

PhilipR said:- “Dirk you’re right, the period between 1945 and 1970 was one of Butskillism”.

No. he’s not. He described the entire period as one of “decades of trade union and old Labour rule” which is a very different thing and a grotesque misrepresentation of the actual history to boot.

You, however, *are* right. R.A. (“Rab”) Butler was an archetypical “one-nation Tory”, of which there were multiple other examples in the party during that era (Macmillan being another, and Iain MacLeod perhaps the most celebrated); all were reformist and undoctrinaire in outlook. Nor was that a new phenomenon: the term goes back to Disraeli, founder of the modern Conservative Party (one could scarcely get *less* doctrinaire than “Dizzie”).

Dirk contemptuously describes the “various conservative governments between Attlee and Thatcher…as never (having) managed to reverse any of the major labor policies”. He totally fails to understand that they didn’t “fail”; they hadn’t formed the slightest desire or intention of reversing the Atlee government’s reforms. To a doctrinaire neoliberal, however, such an attitude on the part of avowed conservatives is utterly incomprehensible.

So much the worse for that doctrinaire neoliberal – and no discredit whatsoever to the praiseworthy open-mindedness displayed by those he dismisses so disparagingly, who included some among the most outstanding British politicians of either major party in the postwar period.

@ Ron Saunders…Thursday, April 4, 2019 at 10:13

I found this puzzling:

First, the money supply is determined largely within the commercial banking sector, not by the central bank’s buying or selling bonds.

Second, if the central bank were to issue bonds believing it would reduce the money supply it would just increase commercial bank reserves and interfere with its own interest rate management policy.

The central bank would then have to reverse those transactions by swapping reserves for the bonds it just issued to keep the interest rate on target.

So bond issuance is not even capable of affecting the money supply.

Here’s an article from Bill’s archive that covers this issue:

“Painstaking, dot-point summary – bond issuance doesn’t lower inflation risk”

@ John Armour … Saturday, April 6, 2019 at 12:01

The link you gave to an article by Bill is not an argument against what I was saying. In no way did I even suggest that bonds have anything to do with “financing” government spending. We are talking about different things, and I am afraid I did not express myself clearly in my original post.

When the federal government issues bonds, it reduces “liquidity” in the domestic economy, providing a safe haven for corporations who would otherwise invest or gamble their money (bonds issued overseas perform a totally different function). Domestic bonds do temporarily withdraw money from the money supply, in effect freezing it in the form of an “asset” (the bond itself), and the money itself ceases to exist until the bond matures, when the bond has to be either rolled over, or the money is re-created and returned to the economy (interest payments along the way can be regarded as simply a leakage of money back into the economy).

In the very short term (before the bond matures) it can give the illusion of reducing the stock of money, just like taxes, and it is precisely this illusion that a government can fall back on when supposedly creating a “surplus”.

Why does it even try to do this? Because it has constrained itself in an election by refusing to raise taxes or refusing continue austerity measures. It is actually a pretty stupid thing to do, and the illusion will very soon be exposed for what it is, but this does not seem to matter to parties in an election with an obsession with “surplus”.

However, I do take issue with your statement that “the money supply is determined largely within the commercial banking sector”. Sorry, this is not true, and assumes a banking or book-keeping theory of money, wherein banks supposedly create money in the process of issuing a loan.

This theory seems to be based on three principles:

First, banks lend money before they have the money to lend, which is normal business practice by the way, but the banks do have to borrow money after the event to cover the loan, otherwise they are insolvent.

Second, the definition of “broad money” (M2) counts bank deposits as part of the money supply, and bank loans are classified as a “deposit”, hence banks seem to create money in the very act of creating this deposit. But this very flawed definition of the money supply totally confuses stocks and flows, and involves much double counting.

Third, setting up a book-keeping entry, with a debit and credit entry , and populated with a few place-holding numbers, does not itself create money out of thin air. What is created out of thin air is simply a loan contract, and it is this contract which is the reality behind the book-keeping entry. Money is not “stored” in the deposit account at all. When someone wants to draw on this account, money flows through it from elsewhere in the bank. With this flow, what the bank is in effect doing is re-circulating existing money at an ever increasing rate, increasing its velocity, but is not adding to the stock. And by the way, this has nothing to do with the false “money multiplier” effect.

The trouble with this false theory of money is that the money supply seems largely determined by the commercial banking sector, and not by the government. It also allows some very confusing arguments that government bonds “would just increase commercial bank reserves and interfere with its own interest rate management policy”.

And by the way, increasing or decreasing the size of the money supply by whatever means has nothing at all to do with price inflation. This is shown theoretically in Bill’s article, where he trashes the Quantity Theory of Money, and has also been demonstrated empirically. See the following article.

[Bill deleted link to site he does not wish to promote]

Banks don’t lend their own money for mortgages. They create the deposit to fulfill their acceptance of a loan contract. They just mark up the loan sum ex nihilo in the customer’s account and their collateral is the loan contract. The customer has the money and the obligation to repay it, after which point the whole thing is extinct except as a journal entry. Pretty straight forward. The Bank of England says this is how it’s done.

RobertH

I was Not agreeing with Dirks conclusions.

I was merely pointing out that the progressive left was setting the economic agenda even in places like Australia where workers’ parties spent most of the time in opposition. We were far better off for it.

Full employment, an effective welfare state, collective bargaining and a unionised workforce ensured labour’s share of the income distribution increased amidst growth rates that would put the neoliberal era to shame.

@Ron Saunders

“With this flow, what the bank is in effect doing is re-circulating existing money at an ever increasing rate, increasing its velocity, but is not adding to the stock.”

This statement I find confusing, because the question here is if the banks are simply circulating already existing money, but not creating it themselves, then where does this money come from?

Because it can not come from the currency issuer – the Government.

A government creates money in it’s citizen’s bank accounts by spending. It destroys money by taxation. The difference between the two is simply the deficit/surplus. But then what it does in the case of a deficit is to sell Government bonds to the value of the deficit. The money & the reserves are then destroyed and the holder of that money is provided with an asset (the bond), aka an asset swap.

Therefore the net money in the system as created by Government spending/taxation is ZERO, and the Government also creates ZERO new reserves.

So where does the money that is in my account come from? And importantly where do the reserves that enable that liability to be transferred to another account, and therefore allow my “money” to function as money come from?

Does the “money” not come from a previously created loan? And were not those reserves that enable my “money” to act like money not initially borrowed from the central bank?

@Mark Redwood

The questions you ask are interesting, and are obviously based on the theory that it is banks that create the money they lend.

Your argument that the Government cannot provide the money for these loans, even though it does create money in its own right, I find quite peculiar, and it probably goes directly to the heart of the whole bank-money theory.

According to you, when the government creates money, it then taxes some of this, and then takes back the rest (even if temporarily) by issuing bonds to cover whatever deficit there is. So in effect it does not add net money to the economy, so that if net money is added to the economy, it must come from banks.

Well, the reality is that governments have been running deficits since at least the Second World War, with a few exceptional years, and the sum of taxation and government bonds has always been less than the that deficit, and the money supply has grown because of that deficit.

Whilst you seem to assume that governments issue bonds to match the deficit, this is not why bonds are issued. Bonds are issued to reduce liquidity when it is judged that corporations have too much spare money on their hands.

Federal government bonds temporarily extract money from the economy by giving the corporations a safe place to save the funds they would otherwise invest or gamble, and it can be argued that, domestically, bonds do not even make much sense when used for this purpose, and we could dispense with them. However, it should be added, in the international arena, selling our bonds and buying other country’s bonds performs a different function altogether, having to do with adjusting the reserves needed for foreign trade, and we could not so easily dispense with these.

The point is that federal government bonds are not issued to cover any deficit, in spite of what the popular press and neo-liberal economists might think, as their belief is equivalent to saying that the government has to borrow to fund its new spending, which is just not true.

So the government does create the economy’s monetary base and adds new money for it to grow, and it is this money that the commercial banks recirculate.

Your statement that “therefore the net money in the system as created by Government spending/taxation is ZERO, and the Government also creates ZERO new reserves” makes no sense.

@John Doyle

Let’s try to cut through some of the mystification propagated by one employee of the Bank of England.

I notice you discuss “mortgages” when talking about bank lending, even though this is probably not the major type of lending.

By focusing on that type of loan, it is easy to see that money is being swapped for and converted into a real asset. There is loan contract on one side, and a real asset on the other, and money is a mere intermediary in this process.

You state that banks “just mark up the loan sum ex nihilo in the customer’s account and their collateral is the loan contract”. There are two things worth noting here.

The first is that in this description the time dimension is ignored. It is true that the loan contract is created out of thin air, at the moment when the loan is created, the bank does not first need money to create it. But then the bank must go searching for real money to cover it, and it usually does so in the overnight inter-bank lending process. If the bank does not eventually (that is the time dimension) source money for the loan, it is insolvent.

The second thing to note is that the bank does indeed “just mark up the loan sum ex nihilo in the customer’s account”, but these are just place holders, numbers that merely indcate the value of the loan. They are not money themselves. In fact, money does not actually reside in any bank “deposit” account.

The numbers in a bank’s “deposit” account merely represent an obligation to pay or repay that amount. This applies to both an external saver, or an external borrower.

External borrowers or lenders do not actually own the money that is supposedly in the “deposit” account. They merely become a general creditor or debtor of the bank. Any money deposited from outside instantly flows through into the banks internal accounts, where it can be and is used for anything. To repeat, the numbers in the account are place markers. Note that “trust accounts” are something different again. The money held in trust is owned by an external person, and the money does reside in that account.

It is easy to get bogged down when talking about mortgages. But have a look at other types of bank loans, an overdraft for example. Here it is easy to see that the overdraft is not money until it is drawn upon, if ever. Whatever numbers represent the overdraft are just numbers, not money. The overdraft is not backed by an asset. Other business loans have varying characteristics, and some are asset backed, and others are not.

Ron, I think you are overcomplicating the methods used by banks regarding money creation. They are authorised by the federal government to create money, based on credit creation operations. That is the BoE explanation. When the Mortgagee gets the sum in his account typically that will be withdrawn in a single operation in favour of the vendor and the numbers get transferred into his/her account, most likely not the same bank. So the money is gone over to another account holder and all the mortgagee is left with is the liability and the sale documents get deposited in the lender’s file.

If you are only seeking an overdraft, with no collateral the bank can fund day to day operations of that and will use its own resources, which will include money from bonds it has sold to the public as well as fees and profit from mortgage loans. It it is short it will approach other banks or even the central bank.

Ron Saunders wrote

Monday, April 8, 2019 at 10:09:-

“@John Doyle

I notice you discuss “mortgages” when talking about bank lending, even though this is probably not the major type of lending”.

@ Ron Saunders

I believe that statement is the opposite of the true situation (it certainly is in the US). Please correct me (with figures) if I’m wrong, but if I’m right it sits oddly with your accompanying sideswipe at what you describe as the “mystification propagated by one employee of the Bank of England”.

It seems to me that mystification was precisely what the writer in question was dispelling. But then you appear to be denying that endogenous money-creation by the banking-system takes actually place. Have I got that right?

@ Ron Saunders

Your answer was interesting in the sense that you answered a question I didn’t ask. I didn’t ask what it was that bonds do. I asked where do the deposits in bank accounts come from, and more importantly where do bank reserves come from.

Because neither of those things can come from Government bonds. Bands can not be used to create deposits nor can they create reserves. In fact the selling of a bond cancels reserves. I understand that Government bonds while not actually being money (currency), might as well be, because they are easily converted in the secondary market. But selling a bond in the secondary market neither creates new deposits nor new reserves.

Currently in the UK retail deposits amount to around £1600B and bank reserves are around 20% of that figure.

Now I understand that deposits are not actually currency, they are a liability on the bank in which they are held. That is, it is not the Government that promises to pay, it is the bank. But the whole point of the banking system is that those liabilities/deposits are accepted in exactly the same way as currency issued by the Government. They are to all intents and purposes equivalent.

What you have in effect are two money creation system, lets call them wealth creation systems running side by side. To argue that the Government does not produce wealth is ridiculous, because quite clearly it does, and you only have to look at the very large amount of bonds they have issued over the years. That is wealth, pure and simple, and although you might argue about whether it is targeted properly, it is still wealth. And to argue that banks don’t produce wealth via a form of money creation is also ridiculous, because banks quite clearly create wealth, although you could argue (and I do), that much of that wealth creation is unproductive and indeed harmful.

And I can tell you where reserves come from – they are issued on demand by the central bank. They don’t come from government spending, nor from selling/buying bonds. The government does not have to spend in order to create reserves (they would create a severe recession if they didn’t though!). Banks need more reserves whenever they desire to increase their loan portfolio’s because they have sufficient credit worthy customers. Those loans become deposits, which can then be spent, just as a Government spends when it sets itself a budget and then buys resources.

@Mark Redwood

This podcast from Steven Hail ‘Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Banking, But Were Afraid To Ask’ may assist in answering your questions.

@JonhB

Thx, I did have a listen to it, although I have to say that it’s a bit rambly… it took them 20 minutes to explain how reserves are used to enable interbank transactions, which was in between saying “it’s very complicated” a lot. It was somewhat unfocused as a podcast… And seeing as I already know how reserves are used to make interbank transfers… I got somewhat bored… Also this was supposed to be for lay people, and I am sorry but if this is how economists explain how economics works, I am not entirely surprised that people are turned off…

And I was interested in Ron explaining how it was that banks were simply “re-circulating” pre-existing money, followed by Ron claiming that Government’s do provide the money for banks making loans. I wanted him to explain how the government does that.

Because they can’t do that through normal Government spending – does he mean that the central bank has the power to create reserves? That is banks are benefiting from the currency issuing power of Government?

@ robertH

Yes, you do have that right. I do not believe in the endogenous creation of money by commercial banks.

It is certainly true that M2, the definition of broad money, includes all bank deposits in its definition of money supply (and banks loans are classified as “deposits”), so it would seem that banks create money by definition. I suppose this widely used definition is why there is such incredulity when I deny that banks create money.

However, I have argued that this definition of M2 is a classic case of confusing stocks and flows, and involves double counting. What banks actually do when they make loans is pump existing money through the economy, and the velocity of money increases.

This increased FLOW gives the illusion of a swollen STOCK of money. But illusion is all it is.

Those who push the book-keeping theory of money (i.e. that banks actually create money) usually argue that since most of the money supply is created by banks, the government only has a minor role to play in adding to and regulating this stock of money. This certainly has major policy implications.

Dear Ron Saunders (at 2019/04/09 at 9:43 pm)

I don’t want to argue this matter but you are misleading people badly. When loans create deposits there is no recycling going on. For example, if the bank does not have the reserves to cover the loans when the deposits are drawn down, they can always get the funds from the central bank. New liquidity. And more.

Please don’t keep posting the same errors on this blog, which is about education.

Thanks.

best wishes

bill

@Bill Mitchell

I apologize for blundering in to your blog and writing things that mislead people. That was not my intention at all.

I now realize that your blog is educational, and I do thank you for taking the time to reply under the circumstances.

Is there an MMT forum in which questions about MMT can be raised? I do support MMT, and am not a troll trying to undermine your authority. but I would like to clarify and debate a number of issues, particularly with regard to the endogenous theory of money.

Thank you,

Ron

Greetings again. Most interesting discussion.

Can someone here please assist?

Regarding the sectoral balances chart in Bill’s analysis, where is the dataset for the red line – private domestic balance?

Thanks,

Alan A

Ron, if you’re a Facebook user, Modern Money (MMT) Australia: https://www.facebook.com/groups/mmt75/ is a great group to join. Dr Steven Hail, from the University of Adelaide, is a member and regularly joins in the discussions there. 🙂

Modern Monetary Theory Forum, another Facebook Group, is worth joining too: https://www.facebook.com/groups/169000293873282/ 🙂

Dear Alan Austin (at 2019/04/10 at 6:18 pm)

Sorry, I meant to reply the other day but it slipped by.

To calculate the private domestic sector balance, one has to treat it as a residual due to lack of adequate data.

The fiscal balance and the external balance come from reliable data sets. So, knowing the sectoral balances identity must hold as a matter of national accounting, you can then solve for the private domestic balance by imposing the sectoral balances constraint.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

The last sentence in Item 11 should probably read ‘unable to access any funding or support’. regards,

Jan

PS. MMT was actually mentioned on the ABC tv’s ‘The Business’ program last night (10/4/19)! They’re finally catching up!

https://iview.abc.net.au/show/business