My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

Reclaiming our sense of collective and community – Part 1

My home town (where I was born and still spend a lot of time) is Melbourne, Victoria. It is a glorious place, at least the inner suburbs within about 3-4 kms of the city centre where I hang out mostly. It recently ‘lost’ its top place in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Liveability Index (most pleasant place to live) to Vienna (Source). One wag thought it might have been because the Economist got confused between Australia and Austria. Economists are easily confused! But the reason I mentioned this is because it is symptomatic of how neoliberalism has reconstructed our realities and degraded our sense of community. The ‘competitive’ narrative, even though firms go all out to use power and deception to fix and rig markets in their favour, now dominates our perception. While I identify with Melbourne and would think a significant part of my identity is linked to that identification, the neoliberal narrative with its distinctive language, aims to reconstruct the community and communities of Melbourne, not as social and cultural artifacts, but as ‘products’ competing with other cities of the world for supremacy. I was thinking about this as I scope out the structure of the next book that Thomas Fazi and I will publish next year as a follow-up to our current book – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017). Thomas and I have advanced our ideas and we will, in part, be focusing on how communities and the nation state work together to advance progressive outcomes. In our first book together, we set out how nation states can operate from a technical perspective and what they should do to provide for a progressive future. In the next book, we will dig deeper into the ways people and their communities have to re-empower themselves. Language, construction, vocabulary, and framing are all significant in this regard.

When I was a post graduate student I was often thinking about the idea that technology is more than an engineering capacity. It also has an ideological dimension.

The debates in those days (and the great Austrian writer André Gorz was central to them) often were centred on whether a socialist state should use ‘capitalist’ mass production technology and ‘Taylorism’, which alienated the worker from their product.

I disagreed with Gorz over his advocacy of a basic income guarantee. But he knew that these innovations were the key to the capacity of early capitalists to take control of production from skilled labour and increase the exploitation rate.

In turn, it spawned the push for mass consumption, so that the profits from the increasing surplus value could be realised.

Workers were de-skilled by these technologies but as consumers gained a vast array of objects that we were told made us happy.

The question was should a socialist state seek to deploy the same strategies. The USSR clearly thought so although their attempt at mass consumption proved to be somewhat less successful.

I recall being at a seminar (at Monash University in Melbourne) where two high-ranked Soviet economists were visiting the university (in the late 1970s).

As an aside, a short time before that, Milton Friedman visited the University and my recollection of that seminar was that he was a good speaker (touting nonsense) and was the first adult that I have observed whose feet did not touch the floor when seated in a standard chair!

During the Q&A session of the seminar with the Soviet economists, who were not short on talking the USSR up, I asked a question which was along the lines of what is the difference for a worker in Clayton (where Monash is situated and historically a major manufacturing area – particularly car assembly when Australia did that) who gets up in the depth of Winter and goes to the plant, earns a wage on a mundane, mass production line, and a worker in Russia who does the same.

The answer given was that the two processes were identical for the worker on one level – the mass production technology used by both the capitalist firms and the socialist state were identical and the degree of alienation was the same.

But on another level – the surplus was alienated from the worker and captured by the capitalist in Australia, whereas the surplus was ‘socialised’ in the USSR and used to advance the well-being of everyone.

So same input generates different outcomes – one for capital, the other, a progressive outcome, for all.

I wasn’t convinced about that and considered that the organisation of production and the type of techniques used, including the human oversight (supervisory arrangements, etc) really matter. I read a lot of literature exploring those themes.

Also as a young academic I traced through all the correspondence that John Maynard Keynes has entered into surrounding the publication of his 1936 – The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

That book represented a major challenge of the neo-classical thought that had dominated policy thought up until the Great Depression.

I provide a lot of background and links to other blog posts I have written about that matter in this blog post – The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking (January 21, 2016).

The relevant point here is that Keynes made a huge strategic mistake in the way he presented his argument in the General Theory.

There can be no doubt that Keynes rejected the claim that mass unemployment arose and persisted as a result of rigid prices, principally nominal wage levels, which prevented the real wage (that is, the purchasing power equivalent of nominal wages) from adjusting to this hypothesised equilibrium level.

That proposition was core neoclassical theory and the dominant view at the time (and probably still – in part, because of the strategic mistake Keynes made).

For Keynes, mass unemployment (which he termed ‘involuntary unemployment’) was always a problem of deficient effective demand (spending). He demonstrated that it would still occur, even if prices were flexible in both directions, if there was deficient demand.

Keynes concluded that even if wages and prices were flexible, a monetary economy could become mired in an under-full employment state, which would need external (that is, government) intervention to push it out of this malaise.

The problem is that Keynes, himself, did not clearly break away from neo-classical propositions and language. In the famous Chapter 2 – The Postulates of the Classical Economics, he examined the demand for and supply of labour, which he summarised with “two fundamental postulates”.

Postulate I related to the neo-classical demand for labour theory and Postulate II described its labour supply theory.

His subsequent analysis in that chapter was a comprehensive and convincing attack on Postulate II, which established that a monetary economy could easily generate mass unemployment even if wages and prices were flexible.

The problem was that to simplify his argument, Keynes chose to maintain Postulate I. That is, he chose to focus on how examining just one significant departure from the neo-classical framework (abandoning Postulate II) could radically alter its results – that is, establish that mass unemployment could occur and persist such that workers were powerless to alter their situations.

This uncritical acceptance of Postulate I meant that Keynes accepted the idea of diminishing marginal productivity (that is, that as employment rose each additional worker would be less productive than the last), a fundamental neo-classical proposition.

In turn, he accepted that there was an inverse relationship between real wages and employment – another core neo-classical idea.

His views were immediately attacked (I outline the historical events and persons involved in the cited blog post above) but the damage had already been done – Keynes’ accceptance of the Postulate I – allowed a ‘bastardised’ version of his approach to emerge within a year of the General Theory being published.

It elevated the idea that mass unemployment must be due to excessive real wages relative to productivity – which was anti-Keynes.

This reconstruction of Keynes became known as the Neo-classical-Keynesian Synthesis (or simply, the Neo-classical Synthesis), meant that the fundamental and revolutionary message contained in Keynes was lost and his insights rendered relatively barren.

This hi-jacking of the General Theory, ultimately, led to the so-called ‘Keynesian’ approach being discredited during the 1970s, even though the discredited approach was a pale reflection of what Keynes had developed in 1936.

The point is that the way one chooses to present their arguments in the public discourse matter more than we often can anticipate.

Keynes thought he was being clever by showing that with a few assumption changes one could get very non-neoclassical results from their framework.

But, equally, his strategy could be considered really stupid, given that he lost control of his own narrative and reinforced the body of ideas he was rejecting.

That was back then.

More recently, I have become interested in human cognition – how we learn about things and form views.

Regular readers will be aware of work I have done with Dr Louisa Connors in this field.

For example:

1. Framing Modern Monetary Theory (December 5, 2013).

2. The role of literary fiction in perpetuating neo-liberal economic myths – Part 1 (September 11, 2017).

3. The role of literary fiction in perpetuating neo-liberal economic myths – Part 2 (September 12, 2017).

4. The ‘truth sandwich’ and the impacts of neoliberalism (June 19, 2018).

Our first refereed journal article together in this project (many more to come) came out last year – Framing Modern Monetary Theory (June 14, 2017).

That literature makes it clear that the way we frame our arguments and the language and vocabularies that we deploy is highly significant in whether our views are accepted or not in the public discourse.

It also sets out a strategic path which allows us to understand how neoliberalism has permeated every area of our life and is so resistant to opposition, even when the material outcomes that are associated with it are so poor.

I have also been reading a lot of literature in the field of social psychology which is why I started to write about Groupthink and cognitive dissonance as a way of understanding how the practitioners of neoliberalism resists change even when their policy agenda has categorically failed to deliver better outcomes for the majority.

Hence my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale.

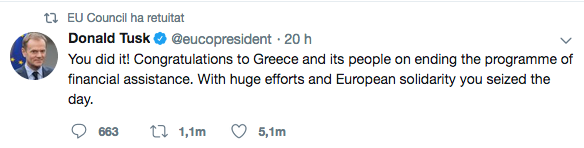

As an aside, think about the Tweet by the monstrous European Union Council President Donald Tusk overnight.

5.1 million people ‘liked’ this indecency.

But the language is of denial.

There was no solidarity. There was bullying, threats, appalling misuse of central bank power, intervention by non-elected outside agencies, and the rest.

Human rights and democracy has been trampled in Greece by a powerful, neoliberal hegemony. To call that a display of solidarity is to lose all sense of meaning in language.

More recently, my blog posts about the British Labour Party and its policy advice were reflective of my concern that progressives do not yet understand the importance of concepts and language.

Just as Keynes made a strategic mistake to conduct his departure from neoclassical thinking from within that very thinking – using its conceptual structure, its terminology, its language and vocabulary, its metaphorical constructs – the modern Left is making the same error.

Spokespersons for political movements (parties etc) seem to think that as long as one espouses what might be considered to be ‘progressive’ goals and policy agendas, support will come from the public.

The same spokespersons also seem to think that that support will be more likely to come if they clothe their narrative in the language and metaphorical constructs of the Right.

They appear to think it is strategically sound to talk in terms of fiscal rules, debt ratios, etc – core economic concepts that have been captured and perverted by neoliberal economists.

I am regularly attacked for being (apparently) ‘politically naive’ when I reject the use terms that I consider reinforce the hegemony of the conservative arm of my profession (which includes all the pretenders who want to mix in progressive circles but espouse an economics that is nothing of the sort).

But a reasonable conjecture is that the constraints these rules and concepts place on government discretion, both directly and indirectly (by their influence on public perception), reduces, if not totally undermines, the capacity of the government to deliver on their aspirational, progressive policy agenda.

I once had a conversation with the then leader of the Australian Greens Party that was gaining ground in terms of voter attraction.

The problem was (and remains) that their economic narrative was pure neoliberal – balanced fiscal outcomes, lower debt etc. I suggested that when the leader uttered these economic ‘slogans’, there were two failures: one, to understand their flaws within economics, and, two, understand that the Party was privileging them and their implications in the popular discourse.

The leader responded by saying that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) maybe correct but as a politician it was too difficult to explain the technicalities etc and so to neutralise that part of the debate the Greens largely accepted the mainstream economic propositions.

The Party then sought to differentiate themselves by concentrating on what mattered to them most – implementing a progressive environmental and social policy.

My response was that the policies are indeed progressive but the Party hasn’t a hope in hell of being able to achieve them because they require a fiscal strategy that their own macroeconomic narrative precluded.

This is the nub of the problem.

British Labour spokespersons might be able to claim that their entire progressive agenda is possible within the fiscal rules being accepted. But come a recession, then what.

Sure enough the rules can be relaxed for a time. But the constant pressure to stay within the ‘neoliberal’ government fiscal parameters would be destructive.

When Margaret Thatcher gave her famous interview to the Women’s Own Magazine (published October 31, 1987) – she said (among other objectionable things):

There is no such thing as society … There is living tapestry of men and women and people and the beauty of that tapestry and the quality of our lives will depend upon how much each of us is prepared to take responsibility for ourselves and each of us prepared to turn round and help by our own efforts those who are unfortunate.

Please read my blog post – Society buckled and is damaged but has never disappeared (April 9, 2013) – for more discussion on this interview.

But she was very cleverly creating a new language about communities and people within them and their relationship to the nation state.

She wanted to create the space to continue implementing even harsher public expenditure cuts which helped low-income families.

She wanted to, in the words of Doreen Massey (from the excellent Vocabularies of the Economy) reclassify:

… roles, identities and relationships – of people, places and institutions – and the practices which enact them embody and enforce the ideology of neoliberalism, and thus a new capitalist hegemony.

She wanted to continue the redistribution of resources and power from the disadvantaged to the rich – to reverse the trends of the social democratic era.

But she wanted to create a smokescreen – that these systemic processes of impoverishment working through the economic capacity of the nation state – were in fact due to the choices and energy that we, as individuals brought to bear in our daily lives.

Individuals create poverty therefore. Blame can be concentrated. As can the solution.

Neoliberals hate society and anything that provides inclusive access to all in the benefits that society can deliver.

Doreen Massey summarised some of her relevant work in this UK Guardian article (June 11, 2013) – Neoliberalism has hijacked our vocabulary.

She talks about engaging “in an interesting conversation with one of the young people employed by the gallery” but when the person turned away she noticed her T-shirt bore the term “customer liaison”.

She thought she was talking to someone about art but realised that her “experience of it belittled into one of commercial transaction.”

Cities are no longer places for communities to thrive and people to live – instead, they tout their ‘competitive’ characteristics relative to other cities and towns.

Doreen Massey says that for an ever-expanding set of daily human activities “we are operating as consumers in a market”.

She says that the “vocabulary we use to talk about the economy is in fact a political construction” and we fail to ask the question “What is an economy for?”, “What do we want it to provide?”.

I can recommend readers to the 2013 special edition of the Soundings Journal – After Neoliberalism? The Kilburn Manifesto – which was a joint effort from many researchers and edited by Stuart Hall, Doreen Massey and Michael Rustin.

It shows that while neoliberalism “set peoples against peoples” and has largely failed to deliver on its over-inflated, self-styled remit (usually touted by economists), “the culpability of the elite is effectively obscured”.

And, in no small part, language has been used to reinforce concepts of the market and competition that perpetuates this obscurity but retains the conduit from the income generating processes in our economies to the elites, while the rest of us, flounder with rising costs and flat incomes.

The authors say:

… the rubrics of neoliberalism, embedded in a common sense that has enrolled whole populations materially and imaginatively into a financialised and marketised view of the world, are implemented when they serve those interests and are blithely ignored when they do not (the bail-out of the banks being only the most recent and egregious example).

That ‘common sense’ becomes unchallenged but contains all the ideological force that legitimises “power, profit and privilege”.

While we are continually told that competitive processes will maximise economic outcomes for the people (lower prices, better products, better service, and all the rest of it), the elites are continually working away to rig the system in their favour – the anthema of competition.

The authors note that:

One key strand in neoliberalism’s ideological armoury is neoliberal economic theory itself. So ‘naturalised’ have its nostrums become that policies can claim to be implemented with popular consent, though they are manifestly partial and limited. Opening public areas for potential profit-making is accepted because it appears to be ‘just economic common sense’.

And this is the issue.

That ‘naturalisation’ of concepts and theories that are manifestly wrong in terms of how they represent our reality are reinforced by the set of myths that go to the core of mainstream macroeconomics.

They are also core concepts that politicians continually tout as if they are knowledgable and aware of the world around them.

When John McDonnell, Britain’s Shadow Chancellor got up to deliver his speech on March 11, 2016 about the fiscal strategy of a Labour government he had two choices:

1. He could break with the language of neoliberal ‘naturalisation’.

2. He could go along with it and thus reinforce or privilege it.

He chose the latter, to his discredit.

He said things like:

1. “There is nothing left-wing about ever-increasing government debts, or borrowing to cover day-to-day expenses.”

2. “Borrowing today is money to be repaid tomorrow.”

3. “With a greater and greater portion of our government debt now held by those in the rest of the world, government borrowing increasingly represents a net loss for those of us living here.”

4. “We shouldn’t be the Party that only thinks how to spend money. We are the Party that thinks about how to earn money.”

5. “Sound finances are the foundations on which everything else is possible.”

6. “We know a rule for spending is needed. It should make clear the framework in which a future Labour government will make its spending decisions so that the public can trust those spending decisions.”

And more.

All of these statements are core terms and concepts used by the mainstream to put a brake on government spending unless it is engaging in socialising the losses of failed capitalist ventures (like bailing out corrupt and incompetent banks).

The vocabulary McDonnell used is core neoliberal.

In the 1940s, Abba Lerner had contrasted ‘functional finance’ which used government’s capacity to advance generalised well-being with the neoclassical concept of ‘sound finance’, which was about attacking and constraining government capacity.

For John McDonnell to say that ‘sound finance’ is the “foundation” that makes “everything else … possible” means he is speaking like a neoliberal and thus reinforcing all the neoliberal frames, no matter how ‘progressive’ his policy agenda might be.

That is why I believe British Labour, like most social democratic political parties in the modern day, are receiving such poor advice.

Adopting this sort of language and framing prevents communities from reclaiming their sense of collective and restoring the notion that we live in societies not economies.

I will write more about this theme in coming weeks.

Conclusion

To be continued …

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Nice that you pointed out Keynes’ error in presenting his theory. Samuelson claimed he came up with the fudge name neoclassical synthesis Keynesianism because he wanted to avoid political controversy and justified it later by contending that, had this frame not been adopted, Congress might have spent like there was no tomorrow. OMG. Joan Robinson so hated this fudge that she termed it ‘bastard Keynesianism’. No wonder it failed in the end, as it wasn’t Keynesian anyway, as you mention.

He made a substantive error in his GT that was pointed out by Kalecki, his theory of investment, and Keynes agreed with him. Apparently, he thought his book needed revision and was working on it, sort of, but died before he could get to it. It is a shame that Kalecki felt that Keynes had written the book he would have written, as Kalecki might well have written a rather different book. It would almost certainly have been framed and argued differently. But, we are where we are.

And the Labour Party are where they are, and I see no indication, unfortunately, that they will change.

Dear Bill,

An excellent wide ranging article. Only tiny improvement is brake for break in 7th last para.

I’m learning so much

You wouldn’t believe how much I want to read an expanded version of that. The intersection of engineering and economics and the philosophy behind -why- such things matter is a very hot topic these days. The last time I commented here concerning distributed computing I was roundly laughed at for supporting “cryptocurrency nonsense”, which taught me there is a very big gap between what is happening at the bleeding edge of computer science and engineering and what people who are interested in MMT understand about the likely future direction of technology.

If you want to deal with notions of “community” properly, you absolutely must be conversant in what community means in today’s digital world. If government is to engage in a meaningful way with groups of people in the future, that interface will be vastly different to what we currently understand it to be, and the nature of that interface will be forever changing. The very nature of government will need to morph into something completely alien to match. So much academic and commercial work is being pumped into this field by very talented people. I so want MMT to have a role to play in it.

From a purely tactical perspective, I think you can learn something about how exceedingly complex technical fields like computer science and cryptographic mathematics can repackage themselves and deliver interesting things that everyday people can understand and use to transform their understanding of how the world works, and how it should work. MMT as a framework for understanding the greater economy is childs play in comparison. If you’re having trouble convincing politicians to adopt its vastly superior message (because that message is hard to sell to a public already invested in lies), then maybe another strategy is needed that delivers it directly to the people. MMT is a technology, and like anything wildly new it requires early adopters to sneeze it into the popular brainspace.

Nice piece. But the persuasion required is immense, because the existing edifice is immense. The potential of the monetary sovereign nation to create huge benefits for society dwarfs what the current ideology can deliver Yet its concept are so marvelously simple! The state can inject money directly into the economy (without borrowing from anyone) that at minimum will increase spending and, therefore, incomes and jobs. Ergo one injects said additional money to cohorts that will consume that money, rather than save it. Health care needs. Educational needs. Employment needs. Food and housing needs. As for investments, the same is true because the nation state requires that a modern infrastructure be advanced. Where the money comes from is irrelevant. It is what the new money creates (wealth) that must be embraced. And where in all this is capitalism? Everywhere. It is as simple as addition and subtraction. What a marvelously simple, yet elegant, narrative. Spend and tax. Add and subtract.

Thank you, shall re-read tomorrow when more awake.

Matt Grudnoff here. They’re stubborn, gotta give ’em that. And still figuratively banging their heads on a brick wall, repeatedly.

https://twitter.com/PaulHenry524/status/1031717106742517760

Bill. I completely agree with the centrality of framing. Friedman. That’s what he was all about; false framing and false associations.

Is it fair to say though that perhaps the best demonstration of democratic socialism working well has come from the Nordic countries and there they have matched high government spending with high taxes rather than especially high deficits? Also labour relation measures such as sector-wide collective bargaining were just as important for their progressive programs. Perhaps John McDonnell is following what worked so well there? I’m happy to be corrected on any of this.

The grip the neo classical vision still seems to have on so many minds, so widely dispersed geographically, and in the face of contrary empirical evidence, would suggest something more than group psychology is at work defending that paradigm. The original series episode of Star Trek ‘This side of Paradise’ comes to mind were a parasitic spore grabs hold of the human mind.

J Christensen, parasitic spore. Very good. Love it.

Bill’s story about the Australian Greens is relevant to Labour today – they simply don’t know *how* to explain how the economy actually operates. I don’t believe it’s ignorance or conspiracy, i believe it’s a rather mundane fear that they don’t have the wherewithal to persuade others.

I think most genuinely progressive politicians who think about it for more than a few minutes would ‘get it’ – having the skill to explain it however is a completely different task. McDonnell and Corbyn simply do not have the skill and intellectual dexterity required for the task. I believe they know it too. So they regress to a tax and spend comfort zone which is where we are now.

A few MMT economists in the HoC would smash the whole thing open, even just one would make a massive difference. Are there any econ professors in the UK come to think of it ? I can’t think of any. Allied with that you need a grass roots movement to push it into the public domain – it’s usually a recession that gives impetus to things like that sadly. Short of all that we could try and clone Bill….

Thanks for the article

Its fresh air from the narrowminded profit market surplus expectation I get everyday.

I work in a research lab and I teach quite a few students. I work my bottom off just to feel unworthy because I am unable to generate profit for a corporate feudal lord.

The brainwashing is so deep that I have no doubt I will go back to my depressed mental state soon. Making profit is seen as virtue and a sign of mental capabilities.

I don’t if this is true but can it be said that university is increasingly training craftsmen who never stop and ask whether something should be done rather than how it can be done.

You can’t make a living with humanities and honest jobs are getting rarer.

A major factor that is not mentioned enough is the Murdoch media empire and its ability to dictate the depth, sophistication, direction and framing of public discourse. The neo liberals are not good at getting their message across, they own and control the venue. They and their ideas would not survive in an unbiased journalistic environment and a progressive political party would be laughed off the stage if they expounded MMT or any socially conscientious agenda because his media empire has already made up everybody’s mind.

Bill said:

“The answer given was that the two processes were identical for the worker on one level – the mass production technology used by both the capitalist firms and the socialist state were identical and the degree of alienation was the same.

But on another level – the surplus was alienated from the worker and captured by the capitalist in Australia, whereas the surplus was ‘socialised’ in the USSR and used to advance the well-being of everyone.

So same input generates different outcomes – one for capital, the other, a progressive outcome, for all.”

It should never be a ‘one or the other’…if a particular worker/producer in society wants to operate under one model and accept the risks/rewards that come with it (such as farm ownership), or they want to operate under the other knowing they’ll always be secure but with no potential financial rewards (such as farming under surplus share) then they should be allowed irrespective of what political party is in town. We have more than adequate legal structures in place to accommodate multiple models.

Another great contribution Bill. It is a sobering thought that people under say 55, have never known a time when public spending for the public good was not only acceptable but popular. It is unexceptional. Framing in terms neoliberal language becomes ‘common sense’ which Gramsci correctly and clearly distinguished from ‘good sense’. Neoliberalism has become the common sense of our era. there needs to be an outlet for expression of these ideas that can reach the community, escape the noise of social media and provide a focal point for opposition. Any ideas?

Mike D

I really enjoyed today’s blog.

Bill, can you pick the precise time that the Monash Uni Dept of Economics went into decline? It would be interesting to compare notes.

Bill, I’m an old guy, Melbourne based, who discovered your work only about 2 years ago. I’m just an ordinary punter who has an interest in economics, politics and society.

I’m so glad I did because you have taught me so much – in fact, probably the best teacher I’ve ever had!

I now have a much clearer understanding of the interplay of money & politics & financial systems and their impact on the lives of citizens.

Your work on MMT has been profound and a major influence on my thinking.

Please accept my sincere thanks for all that you do and more power to you.

PS: As one Melbourne boy to another, who do you barrack for?

Dear esp (at 2018/08/22 at 6:15 pm)

Thanks for the nice words.

Monash was a new ‘red brick’ University that was among many built in the 1960s to cater for the demographic baby boom bubble. It was built on the outer suburbs of Melbourne on a greenfield site – where the urban sprawl in the post War period had spread out to.

So the Economics Department was being developed exactly as Monetarist ideas and then the microeconomic variants (New Labour Economics, Public Choice theory, etc) were beginning to ooze out of the American academy and penetrate central banks and academic departments everywhere.

So it went into decline almost from the inception although it was considered to be a ‘top’ department with a very technical curricula etc. I did a Masters degree there (in the days where you had to complete a 2-year M.Ec before you could go on to enrol in a doctoral program) having come from a fourth (honours) year at the more traditional University of Melbourne. The latter was much more Keynesian in background which reflected its historical position as one of the old inner-city universities.

Monash became one of the key centres for spreading the Monetarist (neoliberal) infestation. I went there because I was offered a teaching assistantship, which helped poor characters like me get through the M.Ec program and onto further studies (PhD).

best wishes

bill

Dear Ian Hughes (at 2018/08/22 at 6:19 pm)

Thanks for the comment and I am glad you have gained something positive from my academic work.

On matters football, I have been a rusted supporter and member of the Melbourne Football Club all my life. I see them play as often as I can.

And … with one round to go … they now have a secure position in the finals for the first time since 2006 – a most joyous outcome for supporters of a team that has mostly been at the bottom of the ladder for the duration of my life!

best wishes

bill

Dean says:

Wednesday, August 22, 2018 at 10:41

“Bill said:

“The answer given was that the two processes were identical for the worker on one level – the mass production technology used by both the capitalist firms and the socialist state were identical and the degree of alienation was the same.

But on another level – the surplus was alienated from the worker and captured by the capitalist in Australia, whereas the surplus was ‘socialised’ in the USSR and used to advance the well-being of everyone.

So same input generates different outcomes – one for capital, the other, a progressive outcome, for all.”

It should never be a ‘one or the other’…”

@ Dean:- Far be it from me to put words in your mouth but if you are (as you seem to be) reading-into Bill’s paraphrase of the answer given by the two Soviet economists to the question he put that he is espousing the Soviet view – namely, that it *has* to be ‘one or the other’ – you are completely misrepresenting his and the MMT position.

He and others have been at pains to make it crystal clear that MMT isn’t prescriptive; rather, that it’s agnostic when it comes to choosing among the whole range of possible policy-prescriptions, none of which are hard-wired into the theory – with the possible exception of the JG.

Further, Bill while making no bones about his own uncompromisingly “left-wing” political beliefs has never AFAIK even remotely suggested adopting the totalitarian Soviet model as a guide.

MMT as such doesn’t clash with your own argument.

Bill,

“This uncritical acceptance of Postulate I meant that Keynes accepted the idea of diminishing marginal productivity (that is, that as employment rose each additional worker would be less productive than the last), a fundamental neo-classical proposition.”

I thought Keynes pulled back from Postulate 1 later on in the late 1930s? (I think it was in his exchanges with Dunlop?)

BTW, I believe Friedman was in Australia in 1975 – sponsored by a stockbroking firm.

Prior to that the Monash Economics faculty was still Keynesian I would think.

About the same time that Friedman was around, Joan Robinson visited also and fairly stirred up the boys in the faculty. It seems, for no long lasting effect.

What was the theoretical basis of the claim that each additional employed person will be less productive than the last?

I am guessing that there was never any empirical basis for the claim.

On what basis can postulate 1 be refuted? My guess is that empowering people with socially valuable, personally fulfilling paid work that provides a living wage can never be less productive than permitting a person to languish in involuntary unemployment.

robertH,

Thanks for your reply.

Are you able to show me where MMT addresses the idea of multiple models co-existing?

What disturbs me is that while our social democratic parties continue with fiscal rules etc, populist right wingers like Salvini and the Lega Nord start sounding very progressive economically, usurping the progressive economic agenda and combining it with xenofobic politics.